. . . barbecue in Wilmington, North Carolina. They cater.

. . . barbecue in Wilmington, North Carolina. They cater.

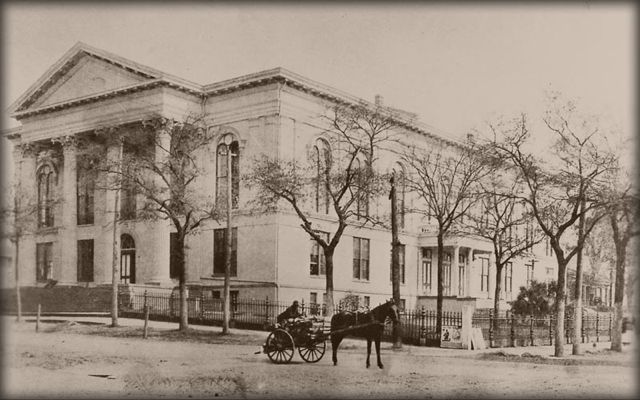

Thalian Hall in Wilmington, North Carolina, my home town, was completed in 1858, using a combination of slave and free black labor. It has a large theater, a grand ballroom and a number of other facilities that have been devoted to various civic activities over the years. Now wonderfully restored, it remains in use as an arts center and town government office building.

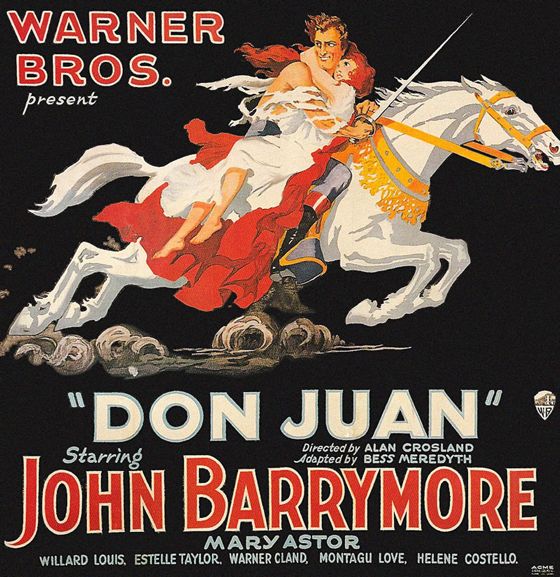

After the unfortunate incident which closed his Washington theater (above) in 1865, John T. Ford managed Thalian Hall for a while.

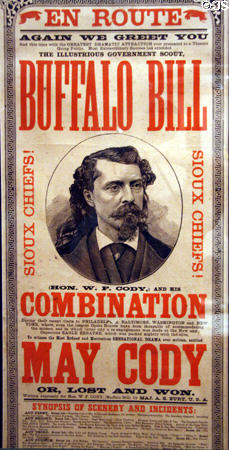

Before he created his great arena show, Buffalo Bill Cody appeared there in a Western play, May Cody or, Lost and Won, based loosely on his life, which concluded with a display of his prowess as a marksman.

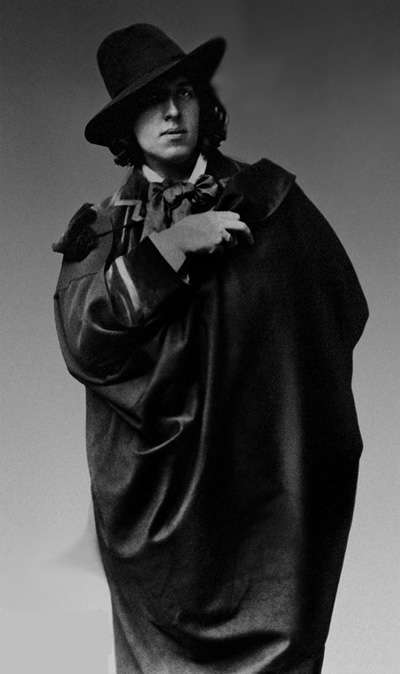

Oscar Wilde gave a lecture there, to a mostly full house. His “exquisitely beautiful” language was noted in the local newspaper.

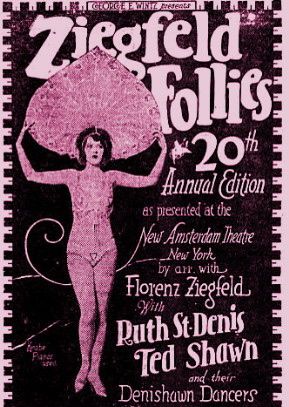

Wilmington's location as the hub of several rail lines made it a town frequently visited by touring theatrical companies, including a road company of The Ziegfeld Follies in 1928, which played at Thalian Hall.

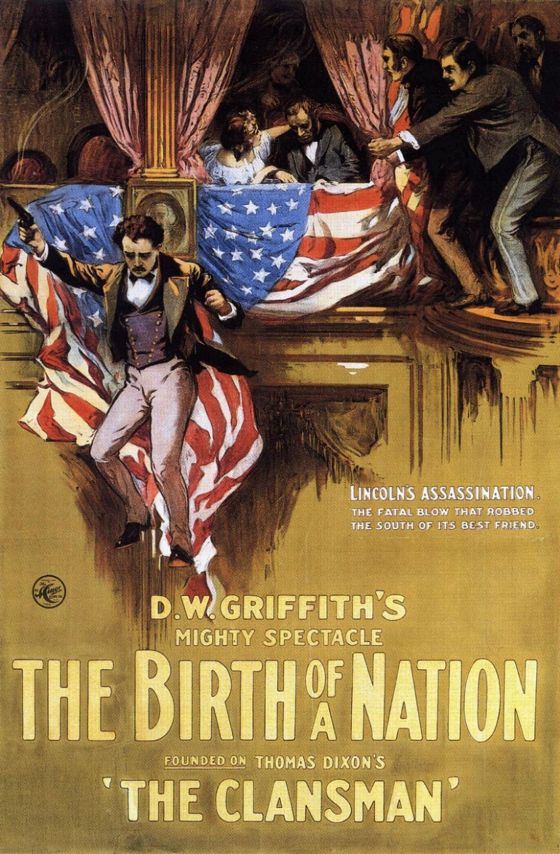

Although rarely used as a motion picture theater in its heyday, the Wilmington premiere of The Birth Of A Nation took place at Thalian Hall in 1916. That film was often booked in legit houses. In the days of segregation, attractions at Thalian Hall played mostly to white audiences, though there were always small sections of the house reserved for blacks. When attractions of special interest to blacks were booked, most of the house would be reserved for them, with small sections set apart for whites.

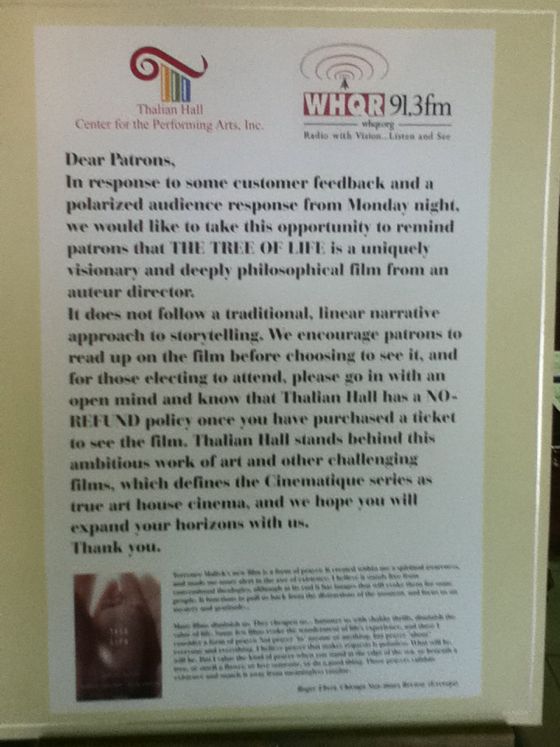

Today, Thalian Hall has an art film program, and I saw The Tree Of Life there this summer. The management felt the need of posting a disclaimer in the lobby (above), warning patrons that the film was unusual. There had apparently been complaints at showings earlier in the week. The film had been scheduled to play in a regular commercial multiplex in Wilmington, but its poor opening at other theaters caused the multiplex to replace it with a different film. Thalian Hall took up the slack.

Thalian Hall is usually thought to be haunted, as well it might be, having hosted so much of the forgotten history of American show business — a grand mixture of highbrow and lowbrow entertainment, though for much of Thalian Hall's existence such distinctions were not made. It was a palace dedicated to all sorts of dreams.

Thalia, incidentally, was one of the nine muses — the patron of comedy. (The wardrobe malfunction in the portrait of her above, by Jean-Marc Nattier, 18th Century, is a reminder that everybody needs to lighten up about certain things from time to time.) The muses were the daughters of Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, all fathered by Zeus on nine successive nights — so it's fitting that Thalian Hall has become a house of memories as well as dreams.

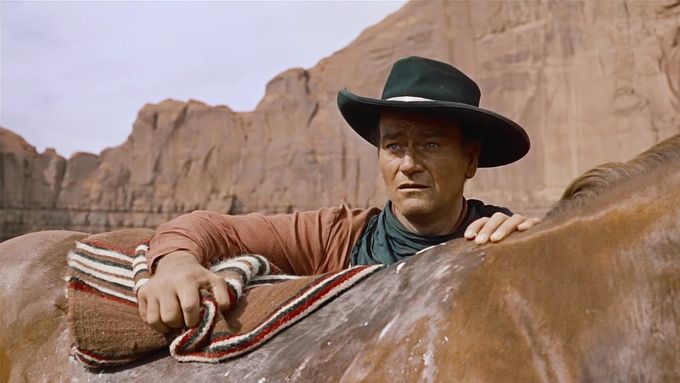

Facebook friend Ray Sawhill has a theory that classic Westerns deal with the themes of shame and honor, which began to feel old-hat in the Sixties when movies shifted more and more to the paradigm of guilt and therapy, following trends in the culture at large.

This wasn’t a universal trend, however — even though it came

to dominate Hollywood (which still has a strong culture of guilt and

therapy) as well as various other self-styled cultural elites — because

whenever a Western dealing with the themes of shame and honor has

managed to slip past the Hollywood gatekeepers, it has invariably found

a big audience. See Unforgiven and the new True Grit, for example.

As I see it, the difference between shame and guilt in this context would be — shame is something you feel because of your own failings, while guilt can be seen as something imposed on you unfairly by others. The difference between honor and therapy would be — honor requires you to make moral choices and take moral actions, while therapy can be seen as something you pay for with cash and consume passively, without the intervention of moral thought.

Therapy strives for vindication and healing — honor strives for redemption, and redemption is the theme of almost every great Western.

You have to have unusual power and authority in Hollywood to get a shame-and-honor Western made, you have to be Clint Eastwood or the Coen brothers, because the industry simply doesn’t understand such movies, and to the degree that it does understand them, it hates them, even when they make a lot of money — perhaps especially when they make a lot of money. If there ever is a full-scale revival of the traditional Western, it will have to originate outside of Hollywood.

Endpapers, unknown book.

No matter how strong the current, no matter how treacherous the sand beneath your feet, keep your beer above water at all times.

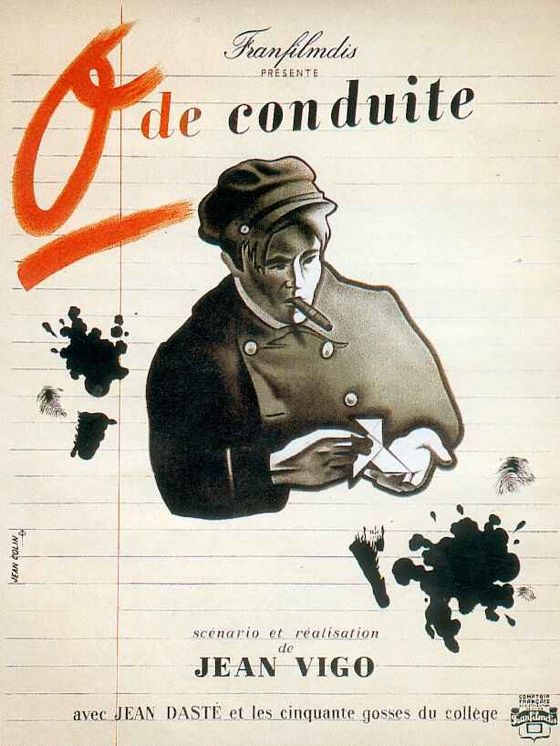

There are quite a number of great films about children, about the world of the child, but Jean Vigo's Zéro de Conduite, from 1933, is the only great film I can think of which feels as though it was made inside the world of the child and smuggled out like contraband past whatever Iron Curtain of time or experience separates adults from that world. It is as though the film was created by a preternaturally intelligent 14 year-old for other preternaturally intelligent 14 year-olds. It's flattering to feel so addressed — like having a 14 year-old punk assume as a matter of course that you will want to join him in vandalizing an abandoned garage. It takes you back — not as the mind takes you back, but as some powerful sense memory does.

Baudelaire said that genius is the ability to summon back childhood at will, and all art on some level summons us back to childhood, to the vividness and innocence of sensation we associate with childhood, but when an artist depicts childhood itself there is almost always some wistfulness in the process. Bergman's great resurrection of the world of his childhood, Fanny and Alexander, is suffused with a sense of loss, a sense that ghosts are being summoned. Truffaut's Les Quatre Cents Coups, which owes so much to Vigo's film, has another kind of wistfulness, a moral wistfulness, asking us to judge, as adults, the wrongs done to children. When Antoine Doinel looks questioningly, almost accusingly, at the camera at the end, we know it is the world of adults which is being questioned and accused, and has been questioned and accused throughout the film.

But Zéro de Conduite is perfectly free of wistfulness, and of special pleading. The hatred of unjust or preposterous adults is visceral and without nuance. Vigo was an anarchist by political persuasion but the film is not a manifesto — it expresses in purely emotional terms the way fatuous authority figures made him feel, in his gut. And the high spirits of the kids, their love of disorder and transgression, are mirrored in the way the film is constructed.

A short episodic narrative about the insurrection of a group of boys at a boarding school, it refuses to stick to one aesthetic strategy. Images with the tone of lyrical documentary give way to dreamlike sequences that seem to record the imaginings of the boys. More or less conventional narrative passages are punctuated by blatant camera tricks, which call up a vision of the filmmaker sticking out his tongue at the audience.

Crude slapstick bits alternate with scenes of victimization suffused with an almost tragic aura. The film moves with the imaginative, nearly chaotic speed — and with the electrifying energy — of a child's mind. The result, however, is not disjointed or disorienting, because the mind driving it is a recognizably coherent mind — just wilder and freer than an adult's mind can often afford to be. In the whole history of cinema there is nothing else quite like it.

The smell of the Evinrude

Gasoline and oil

The curve of the open wooden boat

The high prow

As his father and his father's friends

Launch it into the surf

Timing the waves to crest them

And they will return with tales

Of the ocean beyond the surf

And fish packed in ice boxes

Which will not quite explain

The beauty of the curve

Of that prow riding the curves

Of those waves, out to open sea

[Photo by Les Zahls]

Come worship with us! We have a smoking section, even for children’s Sunday School classes, and serve Rum Cocos at “coffee hour” after each service. Shoes and shirts are optional in warm weather. We preach the Gospel like a punch in the stomach — it’ll knock the wind right out of you!

Be sure to ask about our Wednesday night Texas Hold-’em/Bible fellowship meetings!

“We do church right!”

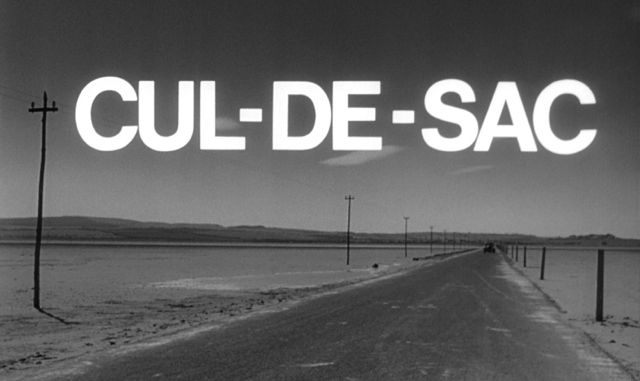

Roman Polanski's 1966 film Cul-de-sac is a slight work — its absurdist nihilism and casual misogyny add up to a fairly puerile vision of the human condition — but it's a wonderfully made film and consistently entertaining. There are hilariously eccentric performances by Lionel Stander and Donald Pleasence and by a fine supporting cast, and the film is beautifully shot in a truly strange location that itself becomes a major character in the tale.

The presence of Françoise Dorléac contributes an unintended poignancy to Cul-de-sac — she would die in an automobile accident a year after the film was released. She doesn't have much of a part — playing the fickle and vapid wife of Pleasence. She takes her clothes off on a regular basis, to remind us that she's the decisive female presence over whom and before whom Stander and Pleasence enact their preposterous duel of wills, but she doesn't seem to have much will of her own. She doesn't help drive the story — she just complicates it and decorates it.

Still, she's so luminously beautiful and fascinating that Polanski can't quite reduce her to feminine inanity — one senses a woman in her who might have given the film real depth and power if Polanski had taken her character a bit more seriously.

Pleasence's character is apparently haunted by an earlier relationship with an unseen “Agnes”, referenced glancingly here and there but whose name becomes a cry of anguish at the end, a summary of something lost long before the film began. But it's Dorléac's name one wants to speak at the end now — dead at the age of 25, leaving only a modest body of work behind her, some of it quite wonderful. What she might have accomplished in this film, had Polanski's not kept such a pyschic distance from her, becomes a symbol of all the work she might have done had she lived.

Jean Vigo's first film, the “documentary” À Propos de Nice, from 1930, can certainly be read as a social commentary — indeed, Vigo himself urged viewers to read it as a social commentary. In the French left-wing circles Vigo moved in, documentaries which offered a critique of bourgeois life or a celebration of the proletariat we're more or less de rigeur.

In fact, however, Vigo was hardly a doctrinaire leftist — he was an anarchist, who never joined the Communist party, and would have naturally opposed any system of reform whose results could be anticipated in detail. He believed that extreme freedom would create its own unforeseeable utopias.

More importantly, Vigo was primarily a visual poet. His portrait of Nice connects most directly with the works of his peers who were interested in creating documentary poems about cities, celebrating their energy in lyrical terms — another reason why À Propos de Nice resists a simple political analysis.

Yes, the film contains ironic and often unflattering images of the idle rich enjoying themselves in a bourgeois playground by the sea — but Vigo seems at least as amused and delighted by these images as appalled. They have the whimsical, endearing, even celebratory quality of Lartigue's photographs of the same class in the same sort of settings. And Vigo's images of the working-class people of Nice utterly lack the heroic quality considered appropriate by more didactic left-wing filmmakers.

Whatever he thought he was making, Vigo in fact created a unique film that celebrates life, energy, movement. It is a reflection of the joy he took in the world as it was — made poignant by his frail health, and perhaps his own sense that he wouldn't have long to enjoy that world. The film ends with images of mortality — statues in a graveyard, carnival figures consumed by flames. As it was, Vigo died at the age of 29, four years after this film was made.

Vigo said that he thought a documentary should reflect not some objective truth about things but a “documented point of view” about things. Ultimately, the documented point of view reflected by À Propos de Nice is simply joy, made sweeter by a sense of the ephemeral nature of joy. The leftist pieties on its surface dissolve into the spirit of the filmmaker — a cheerful, antic, sensual soul, amazed by the world and by what cinema could make of it.

Kendra Elliott's first live-action short, Beatrice and Bob, will have its East Coast premiere at the Woodstock Film Festival on 23 September, with another showing on 24 September:

Screening Times and Tickets

Kendra is a brilliant artist and animator, and a wonderful actor who really helped make Jae Song's Majestic Micro Movie Essays On Cinema special. It will be interesting to see what she does in her first foray into live-action directing.

If you're in the area — check it out!

Maya Allison, husband Mark and baby Casimir have arrived in China for a four-month stay, and Maya is recording the adventure on a new blog — with cool pictures:

The Adventures Of Maya, International Mom

Check it out!

Paul Zahl in the Winter Garden, Florida studio where he records PZ’s Podcast. Here he’s cuing the 100-piece studio orchestra for a dramatic sting to underscore a salient point about the intersection of Protestant theology and the make-up effects of Jack Pierce.

You can listen, free of charge, to all of his podcasts on iTunes.

My mom, two of her daughters and one of her granddaughters in the “smoking section” of Jebbie's On 17, a great down-home restaurant in Hampstead, North Carolina.

Big Nanny's grip on the nation, even in the red states, has grown tighter since I last crossed the nation by car — you can't even smoke in restaurants in New Orleans these days. Between the Republican totalitarians who want to control our sins and the Democratic totalitarians who want to control our lesser vices, the American strain grows weaker . . .