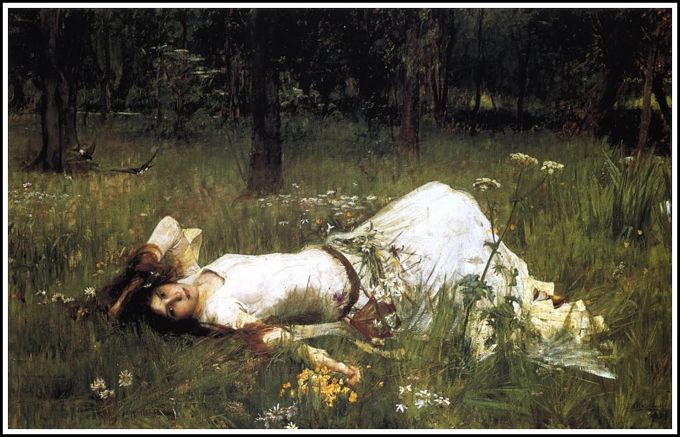

Ophelia, 1889

Ophelia, 1889

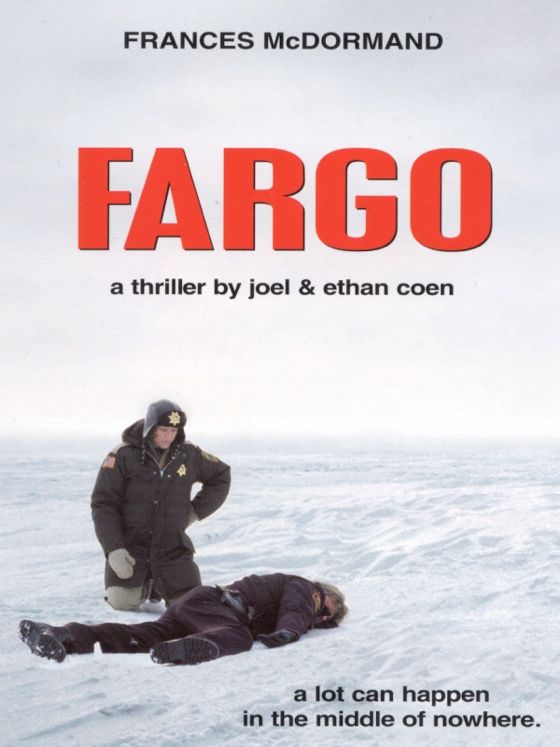

The structure of the Coen brothers' film Fargo is very odd. It starts with a half hour of what is essentially set-up for the tale we'll be watching, and only then introduces the film's protagonist, Marge Gunderson.

This would not make sense if Fargo were merely a crime thriller, as it seems on the surface to be. Instead, like so many of the late works by the Coen brothers, Fargo is essentially a meditation on goodness, on the mysterious presence of goodness in a thoroughly fucked-up world.

The first half hour of the film immerses us in that fucked-up world, so deeply that we think it's going to be the world of the film. This is not troubling, because the treatment of the fucked-up world is so funny, in a dark way, so well observed and so intriguing. We watch as a handful of stupid, immoral louts maneuver themselves into darker and darker realms of disaster, and it's fascinating the way watching a slow-motion train wreck would be fascinating. The lively filmmaking, the brilliant performances, the permission we're given to laugh at the louts — all these things promise a grand entertainment.

And then, suddenly, everything changes — because we are introduced to Marge and her husband, good, decent people in a good, decent marriage. Marge is pregnant. She's also the police chief of the town where the disasters brewing in the first part of the film come to a head in a ghastly way. She's the guardian who has to take the early morning call when things go wrong, in a way that could threaten her community.

She's the one who has to go out in the freezing cold on a lonely stretch of highway to examine three grisly corpses, while dealing with morning sickness. And she doesn't complain. She is cheerful, kind to everyone she meets, but tough, and in her own deadpan way smart as a whip. She's the best of what ordinary Americans can be, the best of what ordinary human beings can be. It's enough to make you cry.

It's enough also to change a crime thriller into a spiritual parable — because now we know that Marge will have the task of tracking down the louts we've already met, entering their world of moral nullity and bringing them to justice . . . or not. The stakes become impossibly high, and sublime. And none of it plays as pious or preachy, because Marge's goodness is funny — we are given permission to chuckle at her relentless decency, the ferocious wit she displays in exercising that decency in situations where decency seems to have no place.

On paper, it must have seemed like an impossible and thankless role, but it was written for Frances McDormand, and the brothers clearly knew what she would do with it — convey intense intelligence in the simplest of ways, skirt the edge of caricature with fine calculation, and be adorable doing it. Adorable and quite often sexy. A pregnant small-town police chief who's sexy.

It's a truly brilliant performance, in a film that is truly brilliant — brilliant on terms of its own devising, that no other filmmakers working today could have pulled off, or even imagined.

Hollywood used to know how to make virtue glamorous — see Casablanca, for example — but the Coen brothers here make it quirky, implacable and utterly irresistible.

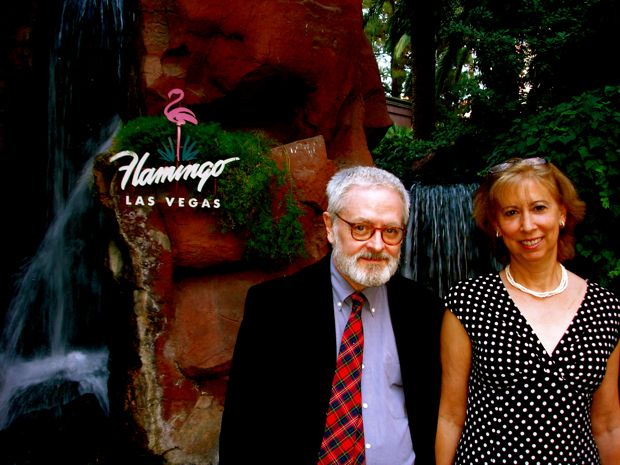

My friend Patty Giovenco (above) rolled into town from Brooklyn on Wednesday to attend the wedding of her brother Carmen, held at the Flamingo yesterday. Since her husband couldn't get off work for the occasion, I got to be her date.

You see lots of wedding parties sweeping through the casinos here, especially around this time of year, but I'd never actually attended a Las Vegas wedding. This one, held in the Flamingo's Garden Chapel, off the pool and garden area (where they keep the live flamingos), was very well done, with a presiding minister who was warm and folksy but serious about the serious things.

Father Ed, a young priest and cousin of the bride who'd flown in from St. Louis, gave a fine blessing that put the seal on the sacramental nature of the proceedings. Besides Patty, I didn't know any of the people involved in this wedding except Carmen, whom I'd attended a Mets game with once, back in New York, but I still got choked up during the service.

Weddings always affect me that way.

There was food and drink afterwards in the newlyweds' suite, where they danced and got wrapped up with toilet paper — a family ritual I had never encountered before. Then a grand feast at Battista's Hole In the Wall Italian restaurant.

Battista's is a venerable Las Vegas institution, dating back to Rat-Pack days, and apparently unchanged since then — the atmosphere is fun, the food is hearty, and a wedding party is excuse enough for everyone seated within sight of it to raise a toast and a cheer to the bride and groom, loud enough to make the welkin ring. Of course there is a strolling accordion player who also dates back to the Rat-Pack era.

The most cheerful of occasions was thus well and truly celebrated — and the bride and groom seemed to be having at least as much fun as everybody else, which is only right.

Walking back to to the Flamingo after dinner, Father Ed suddenly broke out into an Italian song, in a great, sweet, soaring tenor voice. In Las Vegas, this sort of thing just happens in the natural course of events and does not seem strange. Earlier Father Ed had told me that Las Vegas was his kind of town. In truth, it's everybody's kind of town, or ought to be.

I require three things in a man: he must be handsome, ruthless, and

stupid.

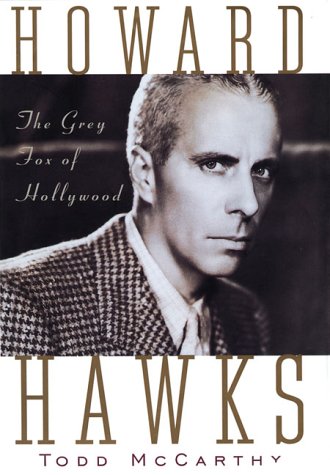

I just finished reading Todd McCarthy's biography of Howard Hawks. It's one of the best of all film director biographies, extremely well-written, entertaining and wise.

Like Ford, Hawks was an elusive man, personally — his second wife called him “a great big pillar of nothing” — but he was a canny and ruthless operator, who played the Hollywood studio game as well as it has ever been played by a great artist. It was his good fortune to want to make the kind of popular art the studios wanted to make, but he always wanted to do it on his own terms, and found ways to accomplish that.

His artistry is elusive, too — so simple and straightforward on its surface that it's hard to see how he manages to tell such exhilarating stories in such effective ways. He probably wouldn't have been a fun guy to hang out with, except perhaps on a hunting trip, but as a filmmaker, he's almost always the best of company.

I live by a man's code, designed to

fit a man's world, yet at the same time I never forget that a woman's

first job is to choose the right shade of lipstick.

Help Michael Almereyda finish his new short film, a timeless tale about goodness in the face of selfishness and suffering:

The Ogre's Feathers

As little as one dollar helps — thirty-five dollars gets you a DVD of the film, a signed note of thanks and a warm sense of service to cinema.

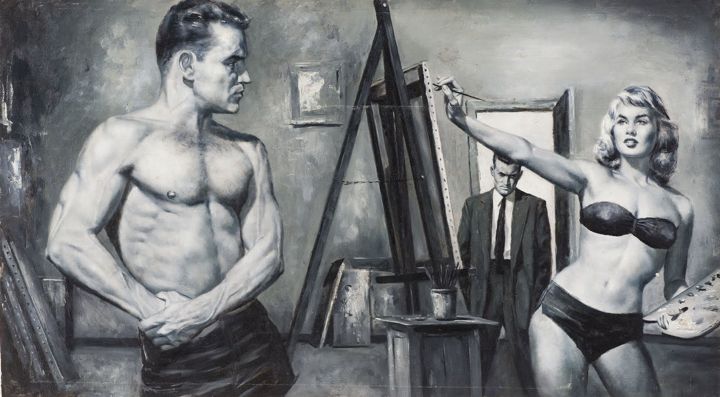

Illustration, For Men Only magazine.

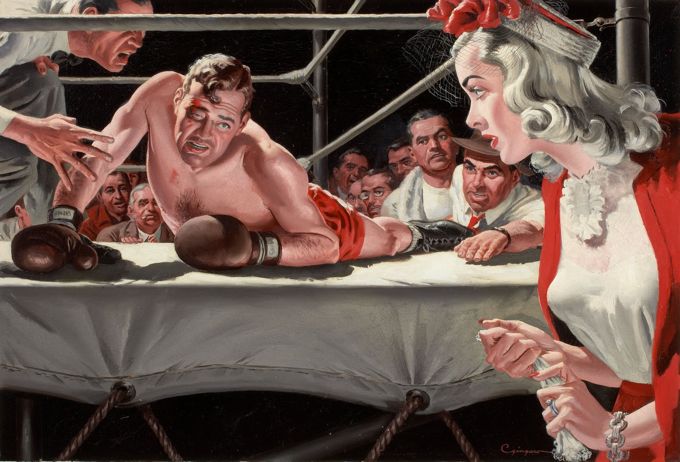

“The Knockdown”, Men's Adventure magazine illustration.

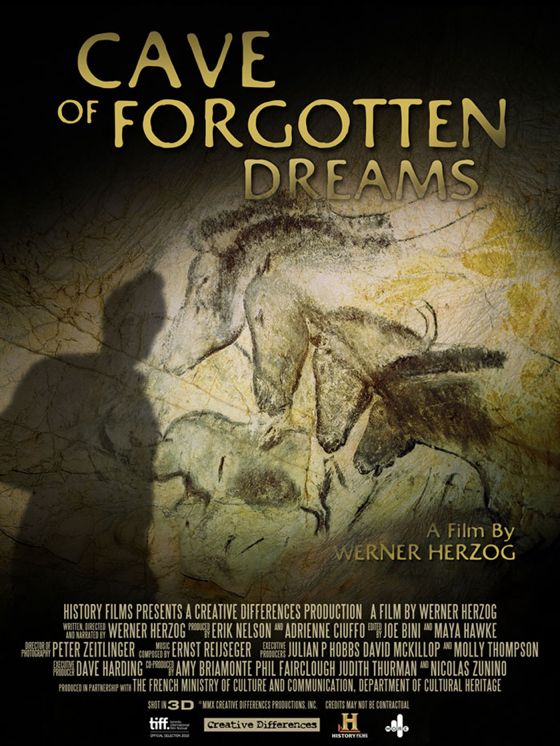

Yesterday afternoon I sat in a dark movie theater in the middle of the Mojave Desert and, thanks to some 21st-Century technology, stared into a dark cave in the south of France whose walls contain what are thought to be the earliest paintings by human beings ever discovered, some 30,000 years old.

I was, of course, watching Werner Herzog's 3D documentary Cave Of Forgotten Dreams. Because of the precious nature and fragility of the cave paintings, the public has never been and never will be allowed to visit the cave, which is accessible only to scientists and historians, but Herzog was allowed to film it to show off its wonders to the world.

The 3D process he used is illuminating, not only because it conveys a visceral sense of the spooky cave environment but also because the artists who made the paintings used the irregular surfaces of the cave walls as elements of their work, often suggesting the physical mass of the animals they depicted, giving the images at times the quality of relief sculptures.

One has to strain to imagine the age of the paintings because they do not look old. They are well preserved, because the cave was sealed off by a rock slide about 10,000 years ago, but the art itself is fresh and alive, and breathtakingly beautiful. The images pulse with desire — they mostly depict animals that were hunted by Paleolithic men for survival — but also with awe and respect. The animals are rendered with powerful suggestions of movement and grace, their beauty as living creatures fully appreciated.

Here, for example, are the earliest painted representations of horses, and they can stand as works of art alongside the horses of the Parthenon Frieze, the Byzantine Horses of San Marco, the horses in a John Ford film. They summon up the vital spirit of horses in the flesh and in movement.

Human beings have created no greater works of art in the 30,000 years that have passed since “primitive men” crafted these images. This is humbling in one sense, but also invigorating. The images remind us of what is distinct about our species, this ability to make not just useful things, of increasing complexity, but sublimely beautiful things, of inexhaustible complexity. It's a complexity that transcends the material plane, and can only be called spiritual, and it's found, fully developed, in Chauvet Cave.

Our ancestors were fully human when they made these works of art — when one of them stenciled the outline of his hand on the cave wall — and we can look at them to remind ourselves what being fully human means.

American Cemetery, Omaha Beach.

There are many forms of service and sacrifice for one's country, but no one can give more than they gave, which was everything they had — all their tomorrows for us and our tomorrows.

Ernie Pyle, the great poet of the dogface solidier in WWII, once told an interviewer that he never ceased to be amazed at the casualness with which an American soldier would lay down his life for his fellow soldiers. “And they didn't do it for parades or statues or glory,” Pyle said. The interviewer asked, “Then what would be a fitting memorial for a soldier like that?” “Well,” said Pyle, “the next time you pass a soldier's grave, just stop and take off your hat and say, 'Thanks, pal.' That's what they did it for.”