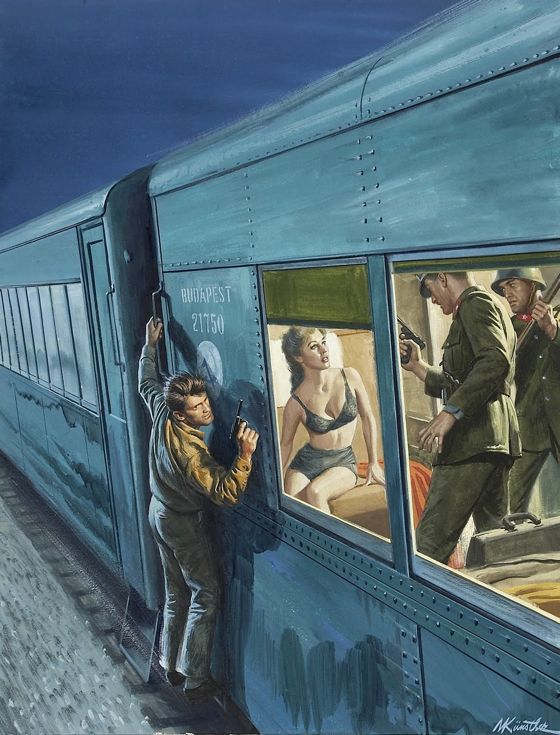

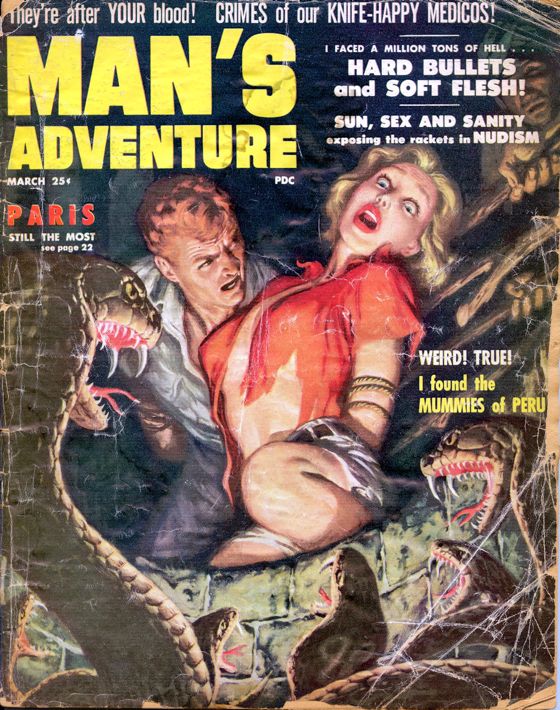

“Freedom Girl's Iron Curtain Escape”, For Men Only cover, June 1964.

[With thanks to Archie Waugh.]

“Freedom Girl's Iron Curtain Escape”, For Men Only cover, June 1964.

[With thanks to Archie Waugh.]

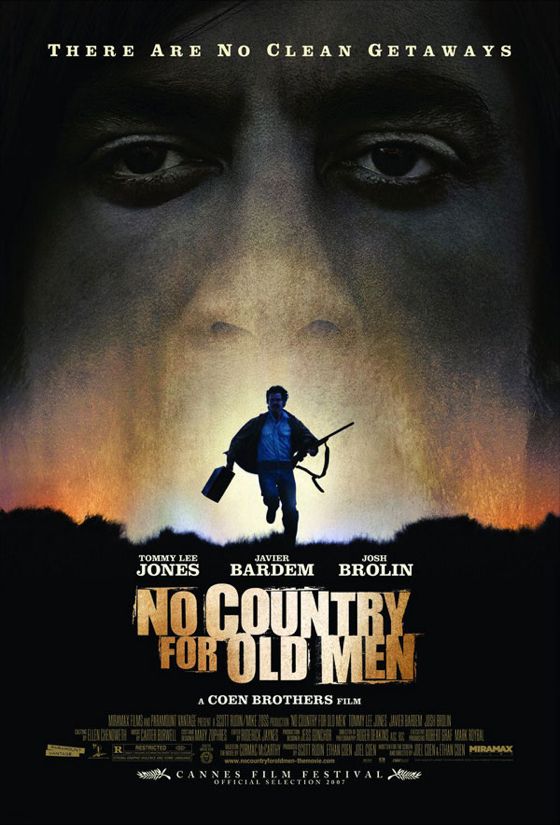

[Warning — plot spoilers below . . .]

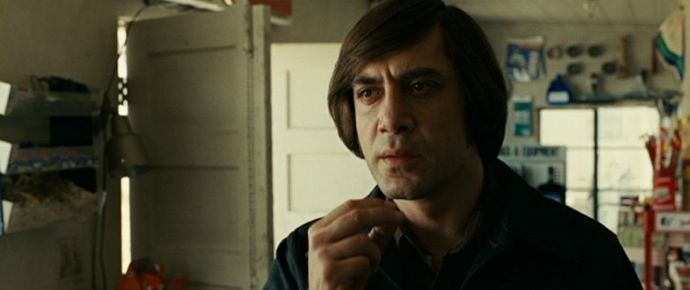

The first time I saw No Country For Old Men, in a theater when it originally came out, I found it extremely disturbing. I couldn't quite identify a coherent theme or point of view, and part of me wished I hadn't seen it, because it was so harrowing. It was much the same reaction I had the first time I saw Taxi Driver.

I suspected in both cases that I had seen a great film, an important film, and subsequent viewings have confirmed those suspicions.

The link between the films has to do with violence, of course, and the way it is presented, which is unusual. It is not in either film overly aestheticized, and it's not used as an occasion for relief from suspense or moral outrage. It is there to disturb and sicken, to create suspense rather than resolve it, to raise moral questions rather than answer them.

Many films, such as the classic Western, use violence to resolve a moral conflict, and I don't object to this, because the Western, like the fairytale, is a fable, a dream — and the violence found in both forms is read as fabulous, as it is in dreams. I do object to most modern thrillers, in which violence is used for sensation — in which a villain is demonized only to arouse our blood lust, to make us rejoice in his demise, with no deeper moral issues involved.

On subsequent viewings it's become clear to me that No Country For Old Men makes a very deliberate and calculated break from the usual formula of a modern thriller, violating convention in a shocking way, and that this is the key to its meaning. In the first two-thirds of the film, the story sets up a duel between a vicious psychopathic killer and a sort of anti-hero, likable but morally compromised. Hovering in the wings is a moral presence, in the form of a thoroughly good local sheriff, who is not directly involved in the duel.

Then, without warning, at the beginning of the third act, the anti-hero is killed, and the decent man takes his place as the film's protagonist. He never engages the psychopath — doesn't outwit or outfight him, doesn't bring him to justice. He simply stands against him as a kind of witness.

Things get almost mystical towards the end. It seems as if the mere presence of goodness can make the killer vanish into thin air — as if the fact of goodness diminishes him, makes him vulnerable, saps his power. He “gets away” but seems to have lost his existential substance.

The universe of the film is very bleak, its violence incomprehensible and thus utterly terrifying. We are not told that countervailing violence on the side of justice can defeat it, only that moral rectitude can stand in the way of such violence becoming the definition of human existence. The film's denouement is purely spiritual, not practical.

It's not much, I guess, but it's so much more than the lies about violence told in most movies today, which do not prepare us for the world as it actually is and thus do not offer us any authentically hopeful or honorable way to live in it.

Tea Room

An amusing publicity shot of Ben Johnson and Mamie Van Doren, courtesy of Paula Vitaris, who hosts a great Ben Johnson fan site here. Paula thinks the photo probably dates from 1949, when both actors were working at RKO, and observes that Mamie seems to be having a grand old time while Ben is wishing he was somewhere else.

Paula recently posted a series of screen caps and a review of Cherry 2000 on her site, to which I contributed some memories of my brief encounter with Johnson on the film. You can find it here, under the date of 8 May.

The Pirate Queen — aaarrrgh!

John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic, never consummated his marriage, which was annulled after a few years. He said his wife was “not as other women”, physically, and one biographer has speculated that Ruskin was put off by the sight of his wife’s pubic hair. Knowing the female nude only through art, he might never have seen such a thing, and might have thought it was an anomaly. His wife later remarried and had several children, so she must have been “as other women” in most respects.

The convention in most Western art, before the 20th Century, has been to present the female genitalia as a hairless mound of flesh without an orifice. (The ancient Greeks, who found the depiction of female genitalia shocking, usually presented them draped, rather than denatured.)

One major convention in modern fashion photography is to present half-clad women who are almost revealing, threatening to reveal, but not quite revealing their genitalia, or nipples.

The photograph at the head of this post is from the notorious ad campaign for American Apparel, which made a splash by violating this convention. It shows pubic hair, and other American Apparel ads have shown nipples.

I myself find this explicitness refreshing. There’s tease involved — the ads don’t show everything — but they don’t fetishize the naughty bits. Indeed, they celebrate them. They also show women as whole beings, rather than as custodians of desirable but forbidden body parts.

Most fashion photography uses sex to sell clothes. To me, the American Apparel ads use clothes to sell sex, which is often the real point of clothes, and seems a far healthier approach.

Rescuing the female body from commercialization and commodification is one of the great tasks that lie before our civilization. The American Apparel ads can’t be said to contribute much to this task, but perhaps it can be said that they’re a modest step in the right direction.

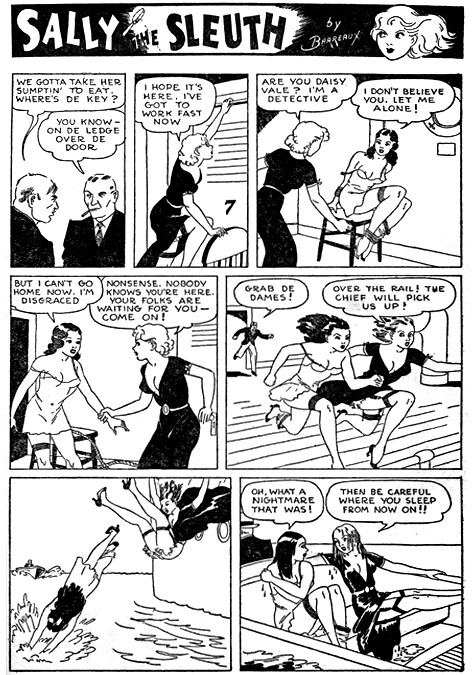

Illustration for The Saturday Evening Post.

By Syd Shores, from 1958.

It's never a good idea to rejoice over the death of another human

being, even the wickedest of human beings. Wicked people want to infect

us with their inhumanity and blood lust, and if we succumb we give them

a kind of triumph. I cried when I heard that Bin Laden was dead — it

took me right back to 9/11, when I watched the Twin Towers come down

from my terrace in New York — but his death doesn't bring closure or

reparation, just a kind of crude emotional release.

The world is a better place without Bin Laden, and he summoned his own

death. He had it coming — but we've all got it coming. Now is a time

to rejoice over the courage of the special forces who risked their

lives to put an end to Bin Laden's murderous career — but it's also a

time to pray for Bin Laden's immortal soul, and to meditate on the

mystery of evil, which his death has not put an end to. It's a time to

resolve to be something different than he was.

Weep for the Bin Ladens of this world, in a way he could not weep for

those he killed.

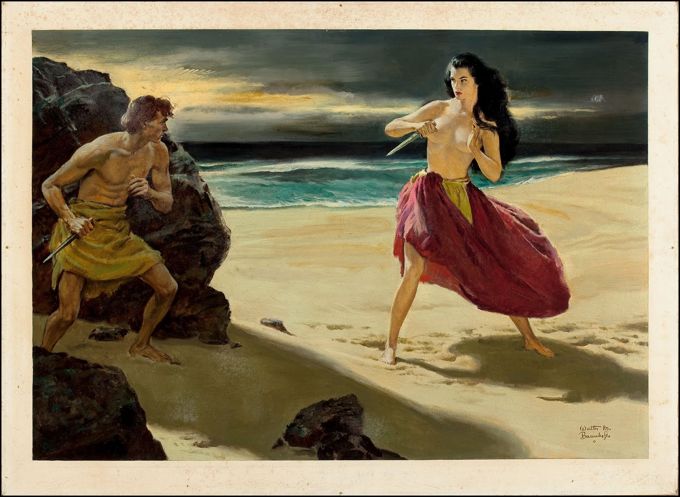

From 1936, when they still knew what “spicy” was all about . . .

Paul Zahl and Bill Bowman, robbing tombs in New Orleans last week.

When these guys were teenagers, and I was, too, we used to make 8mm monster movies together. Time has played havoc with us in many ways, but we remain utterly untouched by maturity.

My friends Kevin and Darci after taking blue ribbons in separate events

at the Funkhana, an amateur rodeo competition at Tanque Verde Ranch in

Arizona. Kevin was an experienced horsebacker, Darci not so much, but

she willed herself into first place in a state of excitement which the

horse picked up on, somehow understanding that he and Darci could not lose. Watching the performance, Kevin said, “Look, Lloyd — two beautiful creatures being hysterical together.” An image from golden days long past.

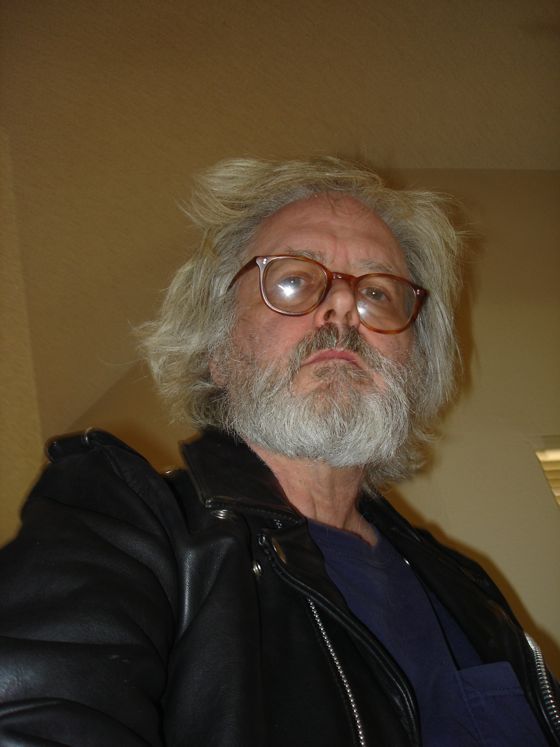

My friend Kevin Jarre was rarely seen anywhere without his Perfecto motorcycle jacket. (I'm wearing mine in the picture above.) He was a motorcycle buff but he wore the Perfecto whatever his ride happened to be at the time — Land Rover, limousine, train, taxicab, subway, horse. He would sometimes consent to wear a sports jacket, for a formal occasion, to get into a fancy restaurant, to please a young lady he was courting, but the Perfecto was his uniform — it was what he put on when he went to work being Kevin Jarre.

He talked me into buying one, and when I did he replaced the cheesy buckle that comes with the Perfecto with a heavier one, exchanging them himself at a leather repair shop where he talked the owners into letting him use their tools. Aside from the buckle, the modern Perfecto is a fine and virtually indestructible object, no different than it was when it was first manufactured in 1928 — the first zippered motorcycle jacket — no different than the one Marlon Brando wore in The Wild One in 1954.

When I heard this month that Kevin had died I pulled my Perfecto out of the closet and started wearing it around town. Sometimes I get funny looks when I do this — I have a tad less style than it takes to wear a Perfecto well. That's what I'm reminding myself of, I guess — Kevin's supreme but eccentric sense of style.

And when I feel the sturdy rivets in the belt loop, where Kevin replaced the buckle, I'm reminded of his generosity and his sense of how things must be.

My friend Kevin Jarre died earlier this month. He was four years

My friend Kevin Jarre died earlier this month. He was four years“Of course I know how to ride a horse,” I said.

“No, you don’t. You don’t know anything about riding a horse. But I’m going to teach you.”

He gave me one of the two McClellan saddles he owned, and one of the

two horses he kept out at a stable in Sylmar, at the northwest edge of

the San Fernando Valley, and we started riding together every day, just

after dawn, up in the San Gabriel Mountains above Sylmar.

Kevin taught me everything he knew about horses, which was just about

everything there is to know about horses. He taught me that the trick

of riding is trying to be as decent and noble and gallant as the animal

who’s carrying you — and to learn how to do it with ease and grace.

I tried to absorb what he taught with my mind, but what he taught were

things you can only learn with your body and your heart. Once, when I

was trying to learn how to sit the trot — not the easiest thing to do

in a McClellan — he said, “Lloyd, can you just forget for five seconds

that you were raised Protestant?”

Sometimes when I’m drifting off to sleep I’ll retrace one of our trails

through the San Gabriels in my mind, trying to remember every turn of

it.

Kevin is always with me on those ghosts rides, and always will be. He

was a fine horseman, and fine horsemen are in touch with something

eternal.

Cast a cold eye on life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!