[Warning — a few plot spoilers here.]

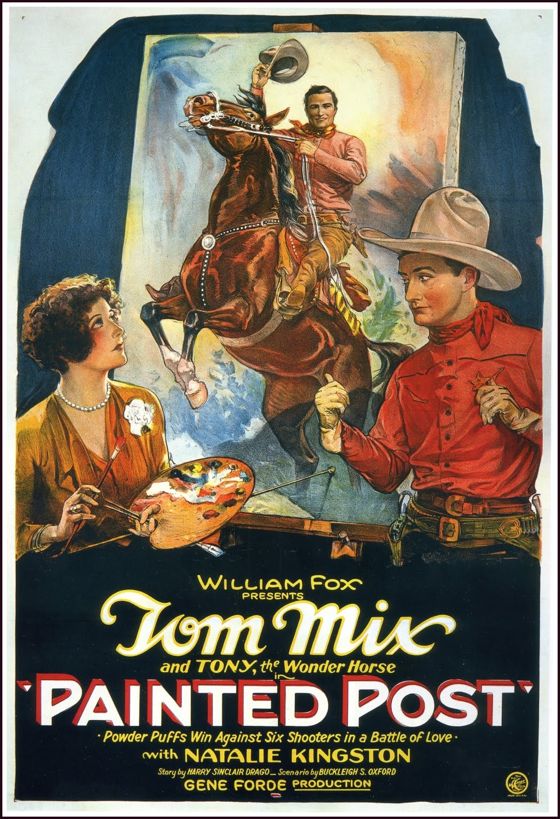

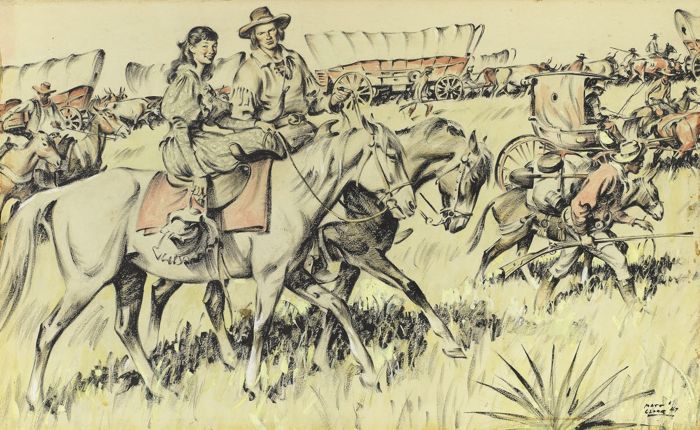

Movie Westerns are about the spectacle of the Old West, of course, about the history of the frontier and America's collective memory of it — but none of these these things quite sums up, much less defines, the genre. The genre has always been a vehicle for showcasing, reviewing, sometimes redirecting but always celebrating American values. It's not concerned with sociology — dispassionately analyzing the actual values Americans have lived by — but with moral aspiration, with stories that endorse the values we think we ought to live by . . . in a form that says, accurately or not, “We have always lived by these values, these values have made us what we are.”

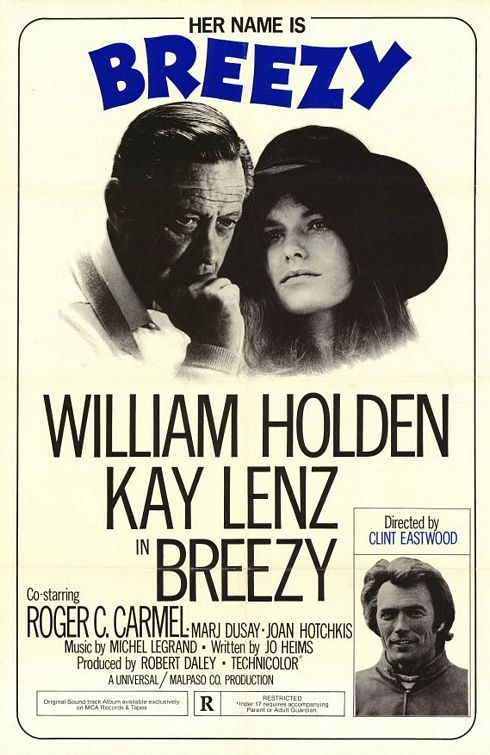

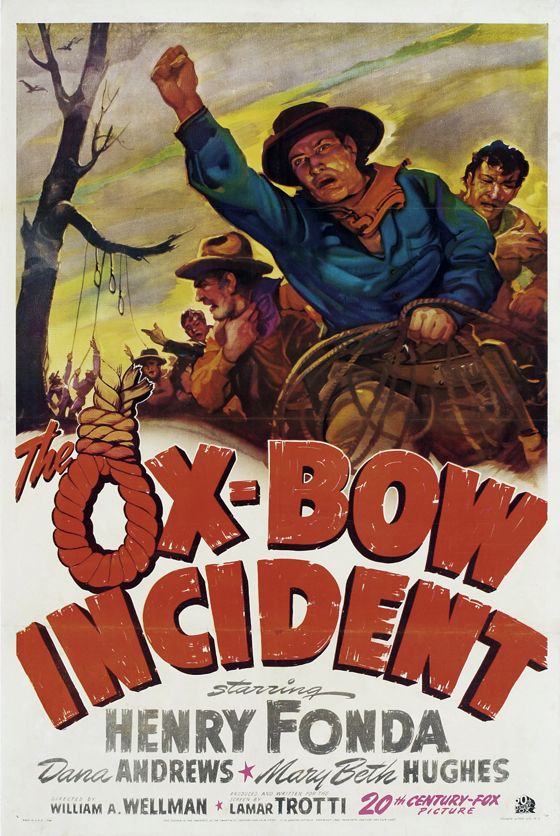

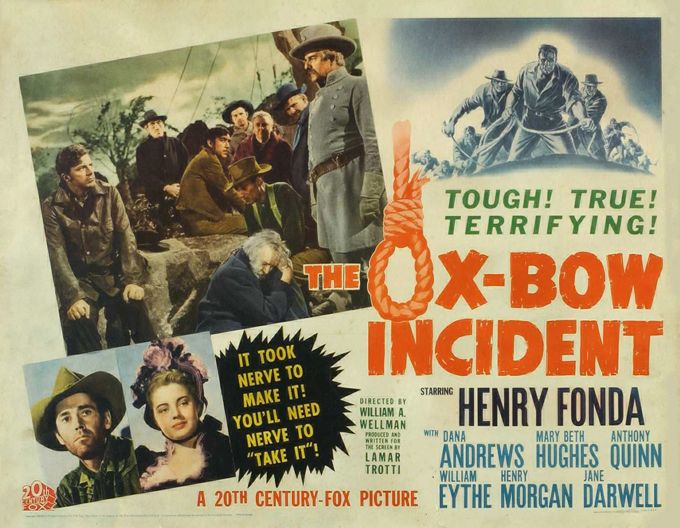

Westerns which don't do this may, like The Ox-Bow Incident, from 1943, look very much like regular Westerns, they may deal with the same themes and feature the same iconography, but they don't feel right. They don't feel like Westerns, and people who like Westerns won't go see them.

The Ox-Bow Incident is a very well-made film, with a compelling drama. But it's based on a novel which offered a kind of critique of the Old West and its values, a critique of frontier justice. Written in the late 1930s, it had a contemporary agenda — it wanted to warn Americans of the dangers of fascism, then rampaging through Europe, and to condemn lynching in other American contexts than the Old West.

It tells the tale of a successful lynching, and shows how decent men can become a party to such a thing. It shows cowboy hero types as complicit in socially sanctioned murder.

These are all valid things to do in the context of a period film, but when they're done in the context of a Western, they disorient audiences. Lynching is a common theme in Westerns, and almost always condemned, but condemned through the medium of the lone hero who stands up to the angry mob and stops it. It may be more powerful, and in some ways more honest and realistic, to make us identify with the hero who can't stop it — to implicate us in his failure. But this is not how Westerns typically work.

Audiences of 1943 stayed away from The Ox-Bow Incident in droves, despite glowing reviews and several Academy Award nominations, including one for best picture, and despite Henry Fonda in the starring role, giving one of his best performances.

The post-WWII, noir-inflected Western showed that authentic Westerns could get very dark indeed and still redeem even a neurotic hero who managed somehow to rise to the occasion at the end and behave nobly. Audiences had no problem embracing these more nuanced and complex and troubling variants of the formula. But with the rise of the anti-Western in the 1960s — Westerns which denied the reality, the validity of traditional American values, which grew cynical about the code of the hero — audiences reacted just as they had reacted to The Ox-Bow Incident in 1943. After an initial bout of enthusiasm, fueled by the novelty of the thing, the frisson of transgression, they stayed away in droves.

They're always ready to come back, however, when an authentic Western appears on the horizon — as the Coen brothers' True Grit recently proved. It's not a hard phenomenon to understand — except, apparently, in Hollywood. The extraordinary commercial success of the new True Grit — now closing in on a quarter billion dollars in international grosses — will undoubtedly lure someone else in Hollywood to try another Western. It will, most likely, be a Western that cynically challenges traditional American values — because that's the hip thing to do. When it flops at the box office, Hollywood will say, “Well, we were right all along. People don't like Westerns. True Grit was a fluke.”

But the success of True Grit wasn't a fluke, anymore than the failure of The Ox-Bow Incident was a fluke. It's all about what Westerns are, what people want them to be — need them to be.