Nation Makers

Nation Makers

This week, Henry's Western Round-up — a blog devoted to news of Westerns in all media — features my Western short story “Tracker” (available here for 99 cents) and an interview with the author.

Henry (Henry Parke) has these kind words to say about the story:

I must admit I was initially intrigued about reading “Tracker”

not for the story itself, but for how it was offered –- as a download

from Amazon, for a Kindle. It only cost a buck, but I hesitated because

I don’t own a Kindle, and don’t even want one, but it

turns out there’s free Kindle Reader software that I could download to

my PC. I’m glad I did.

“Tracker” is a western short story about an unexpected alliance between

a bounty-hunter with a wounded shooting-arm, and a desperate young

woman with a skill for shooting. It’s written in a very crisp and

direct, unadorned style, and it goes places that I did not expect.

While the tone is not grim, let me warn you that elements of the tale

are very dark indeed. I strongly recommend anteing up the dollar.

![]()

The full post is here, and the free Kindle Reader software is here.

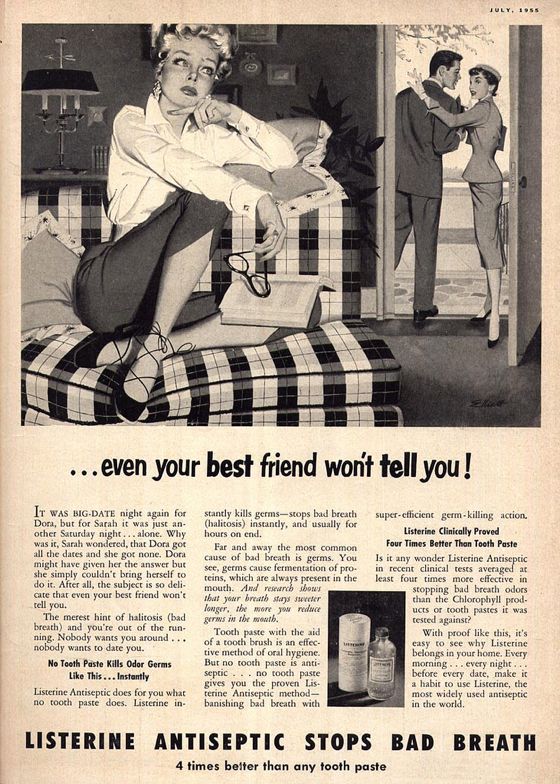

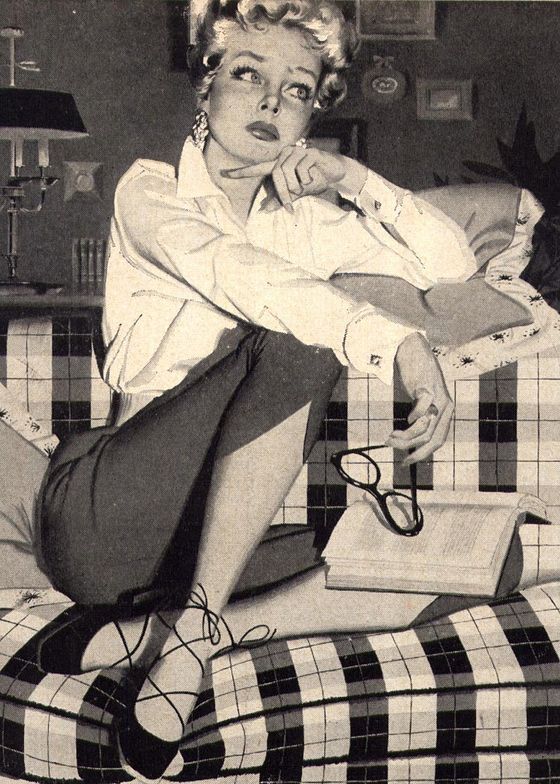

Fans of illustration from the 1940s and 1950s (and of the Mad Men era) should make a beeline to Leif Peng's blog Today's Inspiration, which is a treasure trove of wonderful stuff. The ad pictured was published in Cosmopolitan magazine in 1955.

It was drawn by Freeman Elliot — the detail above reveals a stylish and lively approach to selling mouthwash.

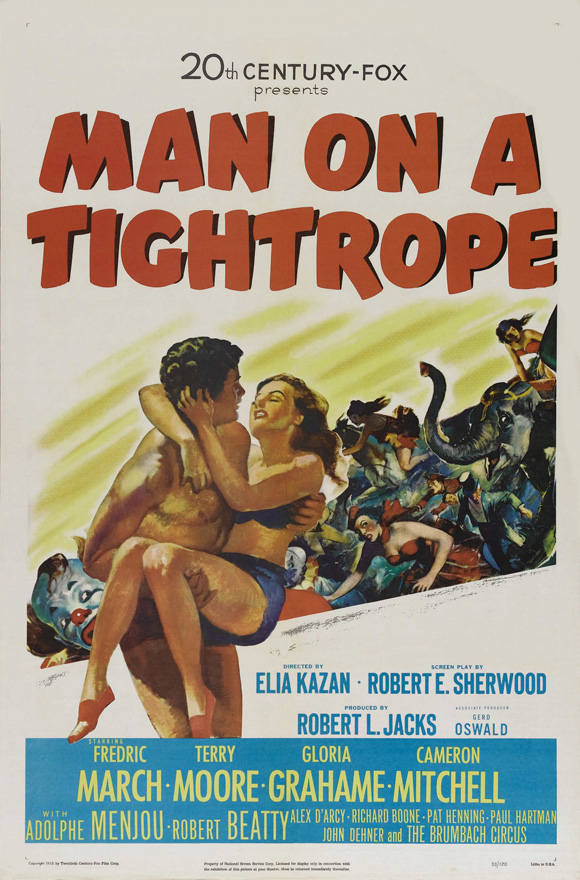

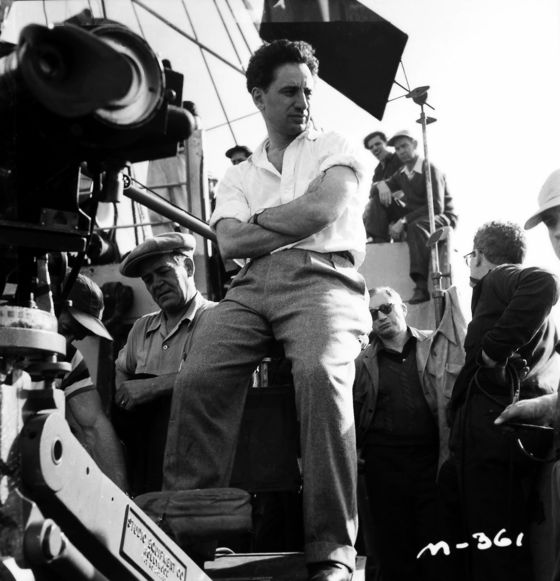

I’d never even heard of Elia Kazan’s Man On A Tightrope until I encountered it in the new Elia Kazan Collection DVD box set, so I was a little surprised to discover that it’s a minor masterpiece. Kazan dismisses it as a misfire in his autobiography, probably because Daryl Zanuck took it away from him and edited it himself. Kazan didn’t like what Zanuck had done with it, and when it flopped at the box office, he may have just wanted to forget it.

It doesn’t deserve to be forgotten.

If Ingmar Bergman had ever made a cold-war thriller, it would probably have looked a lot like this film. It’s about a shabby little circus troupe behind the Iron Curtain which plans to escape across the border to freedom in the West. According to Kazan, Zanuck cut the picture to emphasize the suspense element, losing a lot of Kazan’s nuance and atmosphere, but the truth is that it works as a thriller and has plenty of nuance and atmosphere — beautiful and surreal images of the circus world that elevate the film into an eloquent metaphor for artists struggling to escape restraint.

Frederick March gives one of his best performances as the leader of the circus — quiet, understated, touching. Gloria Graham is as vexing as she often was as his wayward wife and Adolph Menjou has a brief but effective turn as a Communist internal security operative.

The film was shot in Germany, mostly on location, and looks terrific, blending the poetic and the documentary with a sure eye.

It was the first film Kazan made after naming names before HUAC and earning the eternal enmity of progressives, but the interference with the arts depicted in the film echoes the interference attempted on American soil by the members of the American Communist Party whom Kazan “betrayed” to HUAC. It was this interference which caused Kazan himself to leave the Party in the 1930s, and Man On A Tightrope was a kind of defiant defense of his actions, then and later. It reminds us that, however opportunistic and hypocritical the Communist witch hunters may have been, they were hunting real witches — real and ruthless apologists for Stalin and Stalinist methods.

That ought to be taken into account in judging Kazan for “ratting them out”, but none of it needs to be taken into account in appraising Man On A Tightrope, which is a fine and masterful work of art.

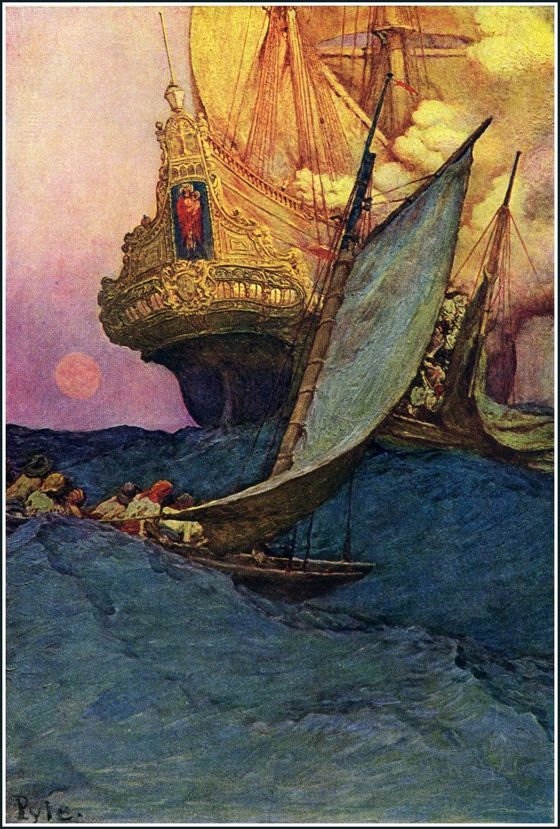

“The Attack On the Galleon”, frontispiece for Howard Pyle’s Book Of Pirates.

In Bed, 1893

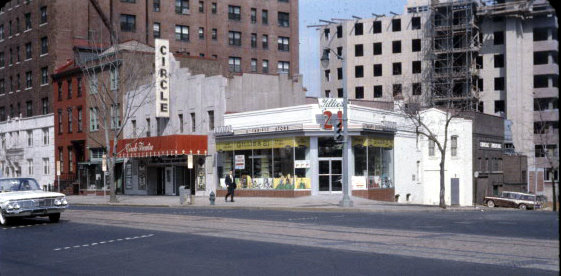

In a recent episode of PZ's Podcast, my friend Paul Zahl paid tribute to The Circle Theatre in Washington, D. C., a now vanished palace of dreams where he and I first encountered foreign films. It was in the early 1960s and we were about 13 years-old at the time, living in an age before cable and home video, when finding “art films” required the sort of effort usually associated with obtaining illegal drugs or firearms.

I'm not really sure what drew us to The Circle, an art house cinema — we were monster movie fans at the time — or what we thought we would find there. We didn't know anyone who either knew or cared much about “art films” and we certainly didn't know anyone who thought they were cool. I know that what we did find at The Circle was a series of revelations about the possibilities of movies, and glimpses of adult sexuality, and the beginnings of lifelong passions for the French New Wave and the works of directors like Ingmar Bergman and Roberto Rossellini.

The Circle was demolished years ago and youth has long since fled, but the wonders we encountered at that theater remain as bright as when we first beheld them.

Listen to Paul's podcast here — The Circle.

See more of Dima Drjuchin's work here — derealization.

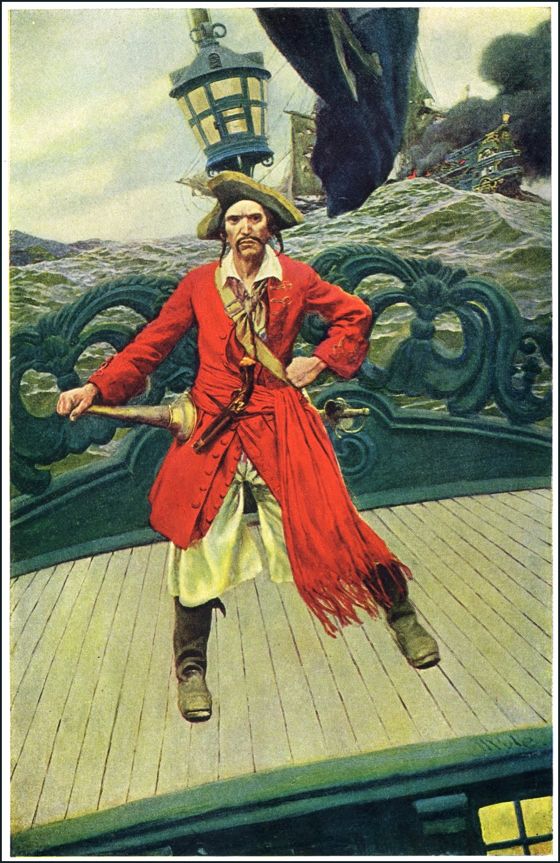

“Captain Kidd”, from Howard Pyle's Book Of Pirates.

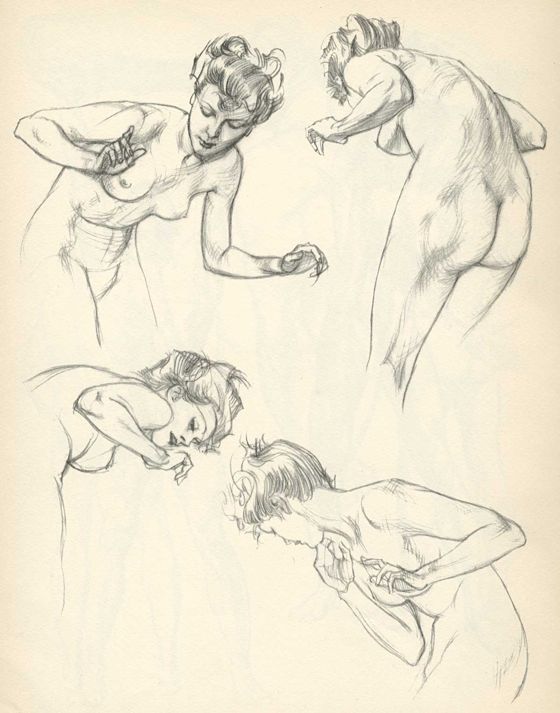

Figuring the angles . . .

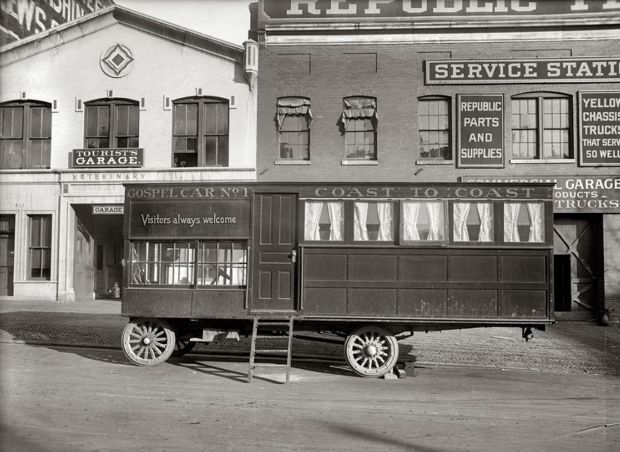

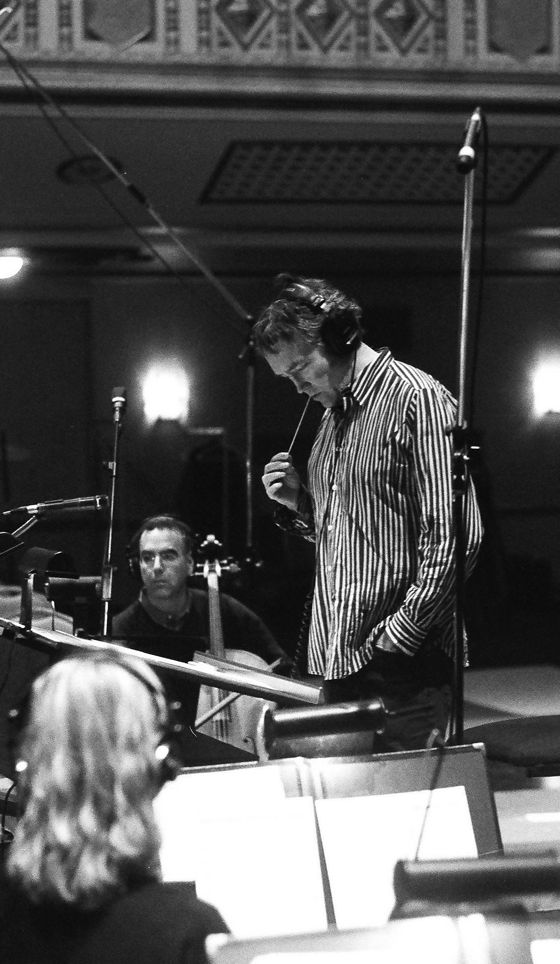

Carter Burwell's score for the Coen brothers' True Grit is one of the finest of recent times — a score inseparable from the film's emotional impact and moral meaning. It's therefore ironic, and actually insane, that it was deemed ineligible for an Academy Award for best score, because it is largely based on themes from old hymns.

From the time of Bach to the time of Bob Dylan, putting old tunes to new uses has been an important part of the work of many great composers. It is, paradoxically, an endeavor in which a composer can most clearly demonstrate his or her originality. Presenting familiar melodies to us in ways that renew them, allow us to hear them in new ways, requires a high degree of imaginative skill.

In his score for True Grit, Burwell works with hymns that are hardly central to the culture these days, but still linger in the collective memory. He rings variations on their melodies that are intimately tied to the moods and themes of the film, and link the film to the musical heritage of America, as the film itself is rooted in the history of the nation and echoes the history of the Western film genre.

Burwell's elegant arrangements don't trade in nostalgia, however, but evoke the severe and demanding faith of 19th-century America — the faith of the film's central character, Mattie Ross. They evoke the grandeur and the dignity of virtue and aspiration, not the narcosis of religious “comfort”. They harken back, as the film does, to what Greil Marcus calls “the weird old America” — the funky, scary, endlessly strange America of a relentless, antic, eccentric people who dreamed majestic things and then cobbled them into existence by any means that came to hand.

Burwell's arrangements have the flavor of the parish hall, of music made communally — simple and unadorned, but inexorable. There is no hint of pastiche about them, or of antiquarian reconstruction — they channel the pure spirit of the frontier.

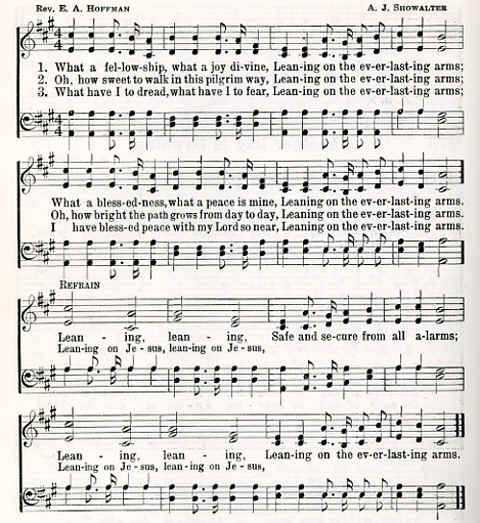

“Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” is the central hymn in the score — it is associated with the “father theme” of the film. We hear it played on a piano over the opening shot of Mattie's murdered father, and then in moments when Rooster Cogburn and Ranger La Boeuf make emotional connections with Mattie, becoming the substitute fathers she so desperately needs. This is an unspoken theme of the book and the movie — speaking it out loud would have turned True Grit into a Disney film, but speaking it in music offers a subliminal and potent emotional reinforcement.

Wisely, Burwell doesn't use “Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” for the climactic set-pieces of the film — he switches gears to strike a bigger and more decisive note. When Rooster rescues Mattie from the snake pit, Burwell uses the melody of “Hold On To God's Unchanging Hand”, which we've heard once before in Mattie's great moment of heroism when she swims Little Blackie across the river, and first earns Rooster's admiration (although he admits to admiration only for her horse.)

The orchestration in the river crossing scene

is grand and noble, almost stately. It does not try to sell the excitement

and danger and suspense of what Mattie is doing, but to emphasize the

magnificence of her courage. It seems to summon up the whole epic sweep

of America's westward progress, and the thrill of every river crossing

in the history of Westerns. It's music that orients us morally to the

scene it's accompanying.

Using the theme again in the snake pit scene reminds us that Rooster's heroism there is on some level a response to Mattie's heroism — an attempt to honor it.

Film scores, especially today, don't often provide this sort of complex resonance with a film's themes — they usually just underline the immediate sensations of the scene in front of us. Burwell is collaborating with the Coens on a profound level here — making the score a participant in the construction of the meaning of the film. It's a stunning achievement, and the Academy has disgraced itself by failing to appreciate it.

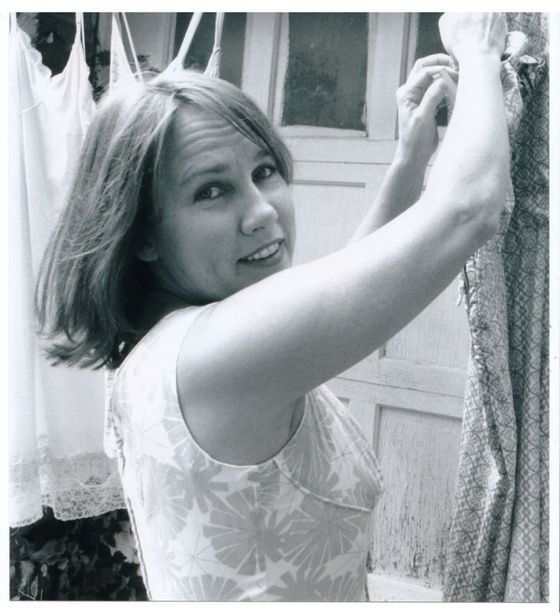

Burwell or the Coens made an inspired choice by playing Iris Dement's recording of “Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” at the film's close. Her performance is very powerful, accompanied by a simple piano and guitar arrangement. Her vocal is both raw, down-home, and beautiful, soaring — she seems to be singing to us from the heart of the 19th Century.

The score is a fine one to listen to on its own, but for some reason the soundtrack CD doesn't include the Dement recording. It's included as a bonus if you buy the album on iTunes, but only in the abridged version used in the film itself. For the full recording, it's worth tracking down Dement's album of sacred songs, Lifeline, which also features a sublime version of “Near the Cross”.

In her liner notes for Lifeline, Dement says, “These songs aren't about religion. At least to me they aren't. They're about something bigger than that.” The same might be said of the hymn tunes Burwell has adapted so brilliantly in his True Grit score. They resonate on many different levels at once, as the music for any great film score does.

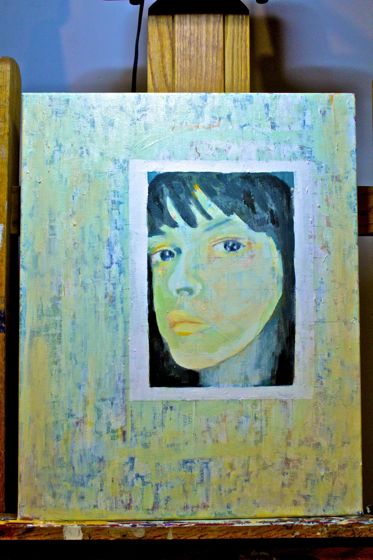

Jae Song, a great cinematographer and director, is also a fine painter. He abandoned his painting for many years, but took it up again recently, and this portrait resulted.

Very cool.

[Image © The Los Angeles Times]

[Image © The Los Angeles Times]

I’ve seen True Grit three times now. I

liked it better the second time than the first, and I liked it better

the third time than the second — although on the third viewing I managed

not to cry until the very end.

I saw the film at three

different theaters, each of which had digital projection. At the first

two theaters the image looked mushy at times, and slightly washed out

in certain scenes. I assumed this was due to the digital nature of the

presentation, but it wasn’t that, because at the last theater the film

looked spectacular — almost like a photochemical print. I could tell

that the movie was beautifully composed and lit on my first two

viewings, but on the third I really got to enjoy the beauty of it in a

more sensual way.

Hailee Steinfeld’s performance seemed

richer and more nuanced this time. The Coens obviously steered her

into doing less than she might have — going for bigger effects might

have exposed her inexperience as an actor — but holding back was also

right for the role. Once you realize how perfectly pitched her

performance is, how complex her reactions really are, you start paying

closer attention to her, and reacting more emotionally to what she’s

doing.

I loved sitting through the previews this time,

because they were so ghastly, like transmissions from another universe

than the one True Grit inhabits. All the “coming

attractions” looked like movies that have already been made, over and

over again — the products of that eternal circle-jerk that is

modern-day Hollywood. When True Grit comes on, you see an

original work of art — based on a novel, and the second film version

of that novel, but alive with new invention and new energy. It’s a

film that will always be brand new.

I think it’s one of the greatest Westerns ever made, worthy of Mann and Boetticher and even Ford — yes . . . even Ford.