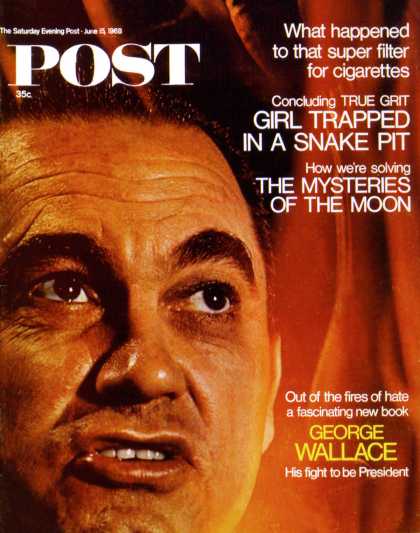

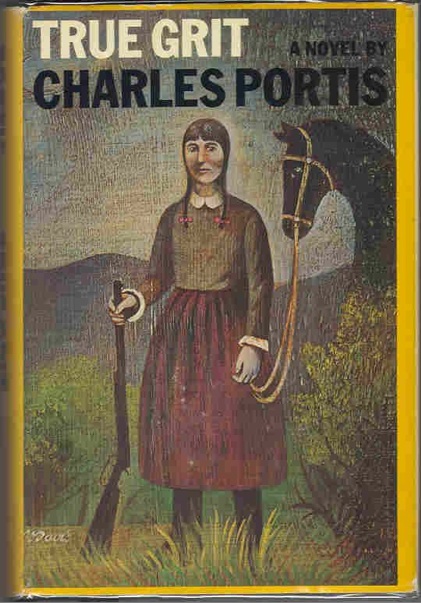

Mattie Ross, the protagonist and narrator of Charles Portis's 1968 novel True Grit, originally serialized in The Saturday Evening Post, is one of the great voices in American literature — one that can stand with the voices of Ishmael, Walt Whitman, Huckleberry Finn and Bob Dylan.

Mattie embodies the contradictions and the mystery of the American character as no other figure in our literature does, quite. How is it that a people so hard-working, tightfisted, materialistic, imbued so deeply with a fun-killing Puritan ethic, nevertheless manages to create characters and legends of such wildness, such free-spirited exuberance, such eccentric moral beauty? There is no answer to that question, ultimately, no way of resolving the contradictions, explaining the mystery. All we can do is observe it, as we observe Mattie, and marvel.

Mattie is 14 when her father is murdered and his murderer flees into the ungoverned Indian Territory of Oklahoma. She hires a hard-bitten U. S. Marshall with a vicious side to go bring the fugitive back, and she determines to go along on the trek to make sure the job gets done. Mattie is a ruthless bargainer in the negotiation, cold-blooded in her determination to see her father's murderer dead — hung by the law, if possible, but dead one way or the other, by any means necessary.

In this she is driven by the ethos of the Old rather than the New Testament — and she is a dogmatically religious person — but her passion is actually more personal than dogmatic. She does not seem to mourn her father, or show a lot of sentiment over losing him — but this is a misdirection. Vengeance is her way of mourning, heroic effort is her way of showing love — and on this unspoken truth the novel turns. For she has found in the man she hires, Rooster Cogburn, a person exactly like her — a seemingly cold tracker and killer of men who has no other way of expressing his values, his profound if often misdirected decency, than by acting as an agent of the law.

In the miracle of finding each other, however, the cold abstraction of the law is overturned. Cogburn becomes a surrogate father, one who will not leave Mattie, either by getting killed or by dereliction of duty. She becomes a surrogate daughter, someone he can love by protecting. They are both redeemed by their love for each other, and the climax of the novel is not the final confrontation with the murderer, but Cogburn's super-human race to save her life.

They remain tragic figures — redemption is not the same thing as satisfaction, as happiness. They have met each other by chance in the only situation in this world in which either of them could truly love another person. But it's enough — more than enough. On their remarkable adventure, they live intensely enough to last a lifetime. They create a story together that transcends their own personal limits as human beings, just as it transcends time. In telling this story, Portis adds another episode of paradoxical grandeur to the American legend.

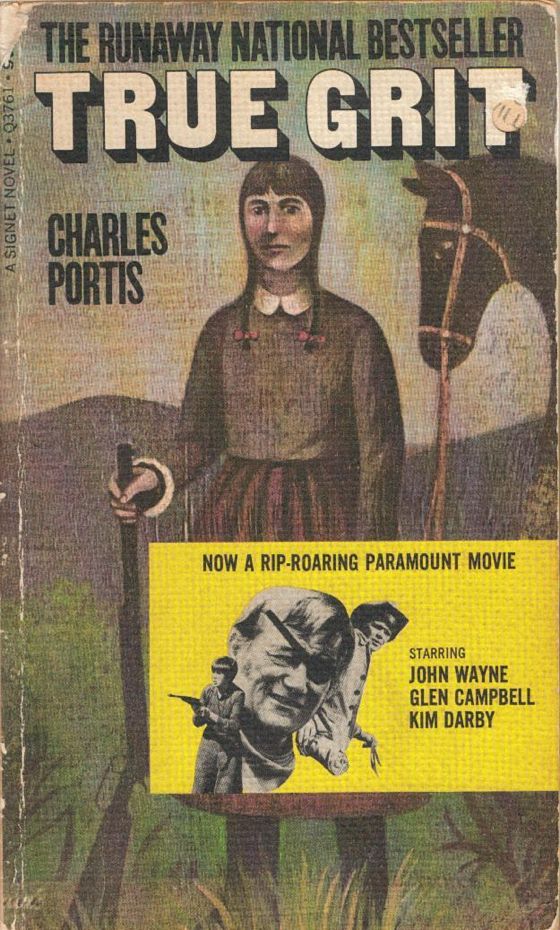

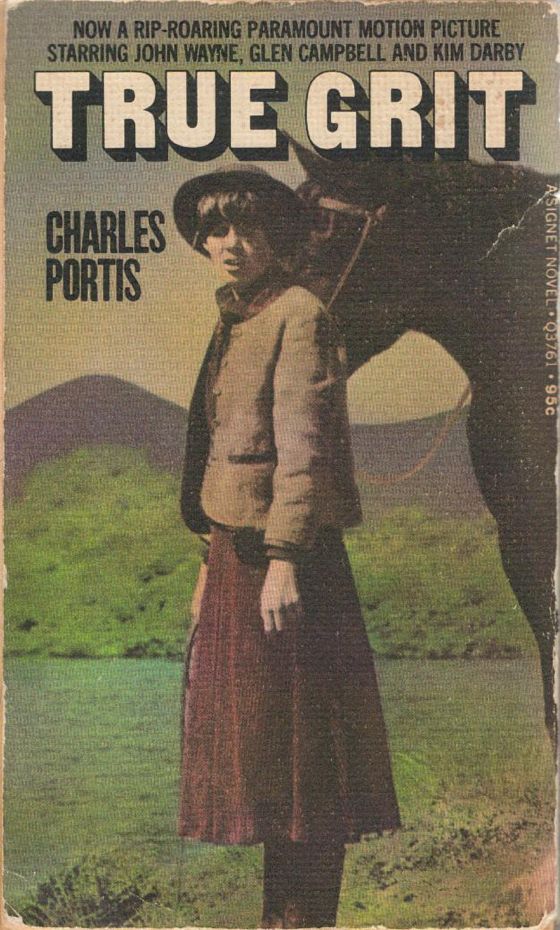

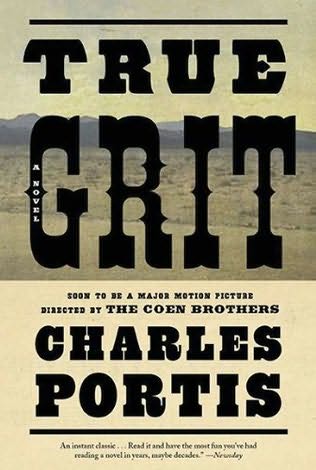

The novel was of course made into a famous film starring John Wayne, in 1969, which has now been remade by the Coen brothers, who reportedly have stayed more faithful to the book. The new film will be released on Christmas Day this year. My guess is that it will be a blessing to our culture, if only by steering people back to a magically profound novel.