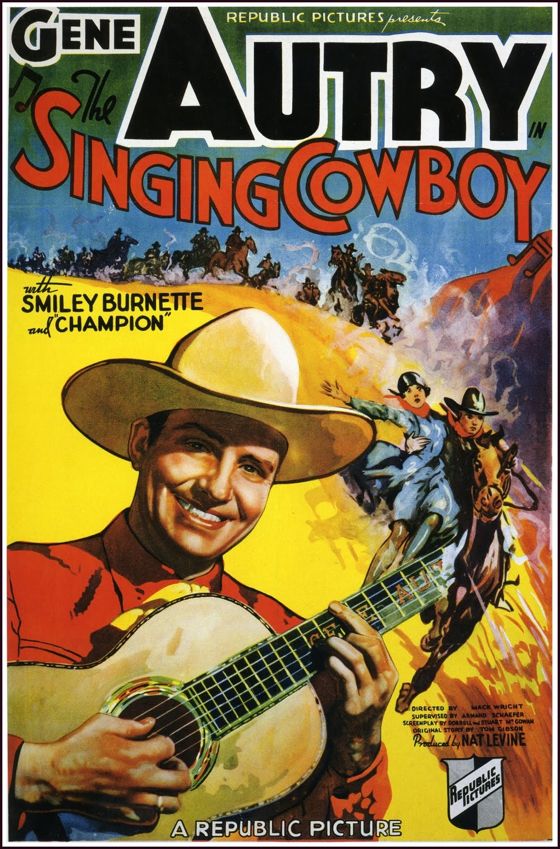

Before the anti-Western there was the twilight Western — a series of films which seemed to sense that the genre was almost played out, or at least that America no longer looked to it for wisdom and inspiration. The iconic Western stars were becoming old men in the 1960’s, and no figures of comparable stature were riding in to replace them, with the possible exception of Clint Eastwood (who would start the important part of his journey far from Hollywood) but the older stars still had box-office pull, for some part of the audience.

So we were given Westerns about the passing of the West, the last days of aging heroes. These Westerns continued to affirm the traditional values of the genre but acknowledged that the world might no longer need them, or if it did need them, no longer understand them.

The twilight Western really began with the last shot of John Ford’s The Searchers in 1956. Ethan Edwards, a somewhat deconstructed hero, walks off alone, having performed his last heroic deed — there is, at any rate, a suggestion that no more such deeds await him.

Ford continued the deconstruction of the Western hero, and offered a look at the times that made him irrelevant, in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence — a film told mostly in flashback. Budd Boetticher had previously made a series of brilliant films starring the aging Randolph Scott, still noble and implacable in virtue, but always alone — not just a lone wolf, like many Western heroes, but marked with a sadness for lost times. The Boetticher-Scott Westerns are uncompromising in their celebration of traditional values, but haunted, too, by a sense of something coming to an end . . . by the idea that Scott’s stoic hero may be the last of his breed.

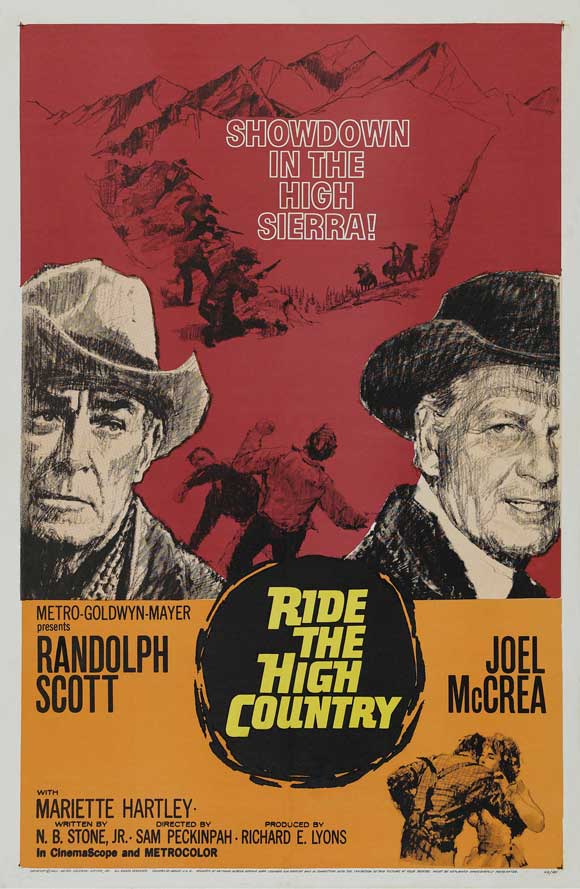

This idea is made explicit in Sam Peckinpah’s first Western (and second feature), Ride the High Country, from 1962. Scott (above on the left) plays an aging hero who loses faith, at least for a while, in the code he has always lived by. Joel McCrea (above on the right), almost as old as Scott, holds on to that code, knowing full well that the world no longer gives it much credit, if it ever did.

The film is an elegy for and affirmation of this old code of

the Western hero — a combination that is both inspiring and poignant.

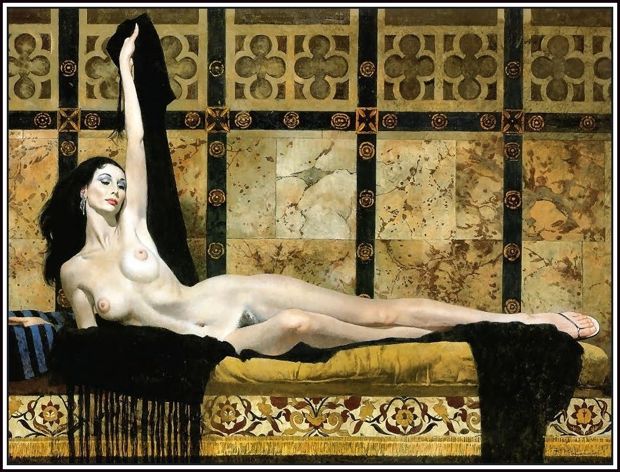

It’s a new kind of Western, too, in its treatment of its female lead, played by Mariette Hartley (above). She offers, as in many Westerns, an occasion for testing the gallantry, and thus the true worth, of the male characters, but Peckinpah makes an effort to get inside her head, to let us imagine what the test means for her. One can’t really call Peckinpah’s perspective feminist, but it’s a step in that direction.

Ride the High Country has taken on a deeper emotional significance over the years, since we now know that the end of the Western genre it seemed to sense was in fact just over the horizon. Curiously, the most successful revivals of the Western have gone back to the twilight theme — Lonesome Dove and Unforgiven, for example, have aging heroes out for one last adventure. It’s a pattern also followed in two modern-dress Westerns, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada and No Country For Old Men, both starring Tommy Lee Jones, of Lonesome Dove. The title of the Coen brothers’ film might have served as the title of Ride the High Country as well. Both films suggest that with the passing of the old men, some hope for the redemption of the new world coming into being has been lost.