Paul Zahl takes a look here at two films instinct with what might be called “atomic-era anxiety”. In America, this anxiety produced the classic films noirs, the neurotic suburbias of Sirk and Ray, the mystical flight of the Beats and countless low-budget sci-fi visions of impending apocalypse. Italy and Japan, losers in the war that the atom bomb ended, seem to have confronted the post-war angst more directly. [As Paul notes, one of the films he reports on, Rossellini's Europa '51, will be showing on TCM this Friday — you have been alerted!] Paul's thoughts on the two films:

TWO FUGITIVES ON THEIR WAY TO THE SAME PLACE

It's always fun to discover something new. In a world I got to know once, the world of academic theology in Europe, you could make your doctoral dissertation in basically one of two ways. Either you could find a new source, some text that nobody knew about

before; or you could mark a new approach (Ansatz) to familiar material.

I was surprised the other night to see, or seem to see, a new approach

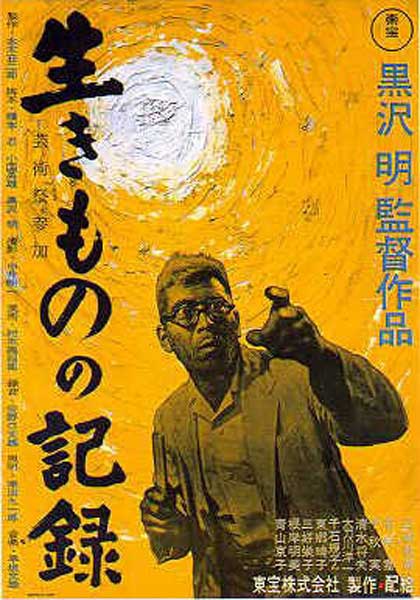

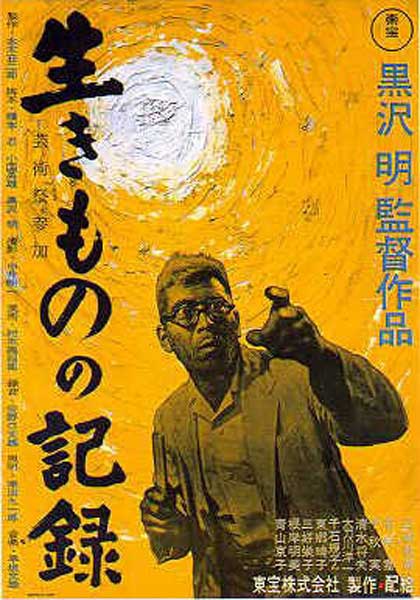

to some familiar material. My wife Mary and I were watching the 1955 film by Akira Kurosawa entitled I

Live in Fear, about a Japanese businessman seized by an obsessive fear

of the atom bomb. The man becomes unhinged, insane, you might say; and

his actions make sure he is committed to a psychiatric hospital. The

question of the movie, however, voiced both by a family court mediator

and an attending physician, is whether the hero, hospitalized and

finally very sick, is the insane one; or whether the world around him,

the citizens of which are going about their business, is insane.

Kurosawa leaves it for you to decide.

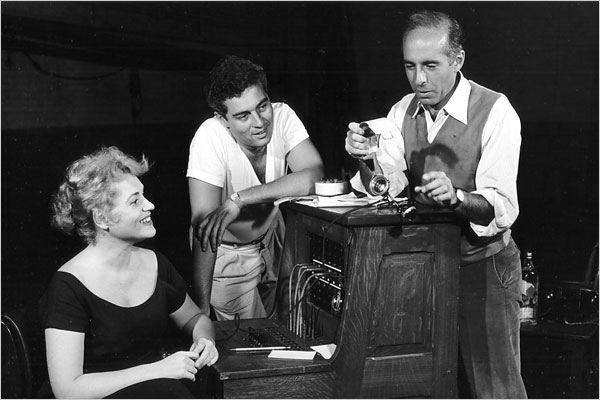

That made me remember Roberto Rossellini's wonderful film with Ingrid

Bergman entitled Europa '51. In this one, made four years before I

Live in Fear, a young mother of means, living in Rome, suffers a

personal catastrophe that unhinges her completely. Initially, she goes

to work, as part of her recovery, on the shop floor of a great factory.

She tries Communism, you might say, in the aftermath of Fascism's

collapse. The well-intended experiment fails. As the implications of

her loss grow clearer and louder, the Bergman character becomes more

and more withdrawn. Finally, after a brief stay in a psychiatric

hospital, where she finds herself identifying, through surges of

empathy, with the inmates, she begins to get better. But, as Rossellini

spins his tale, she decides to make a firm decision to stay in place.

She decides not to return to the world. The final close-up of Bergman,

gazing out from her hospital cell, portrays her as a saint.

As I compared these two films in my mind — they are of roughly the

same date and both come from environments of defeat, which you could

spell with capital letters — they came together. They both point to

heroic “prophets” who renounce and repudiate the values of the world.

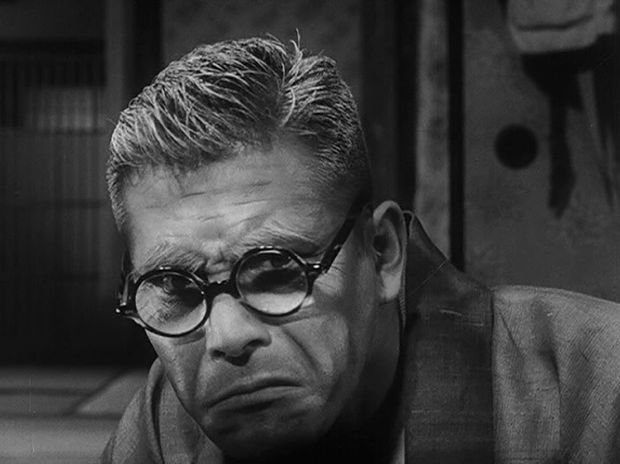

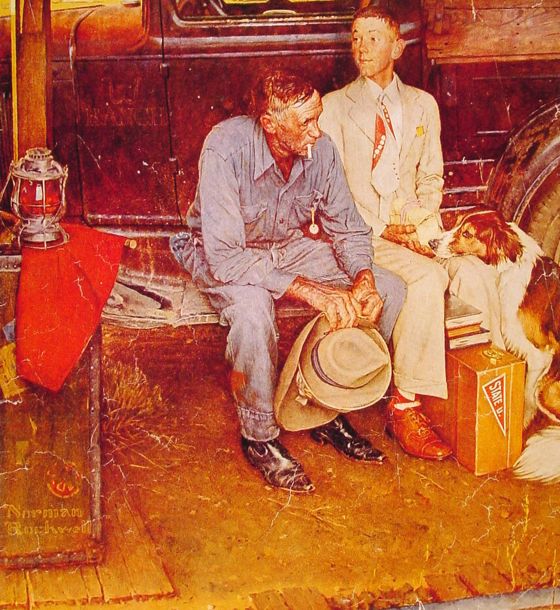

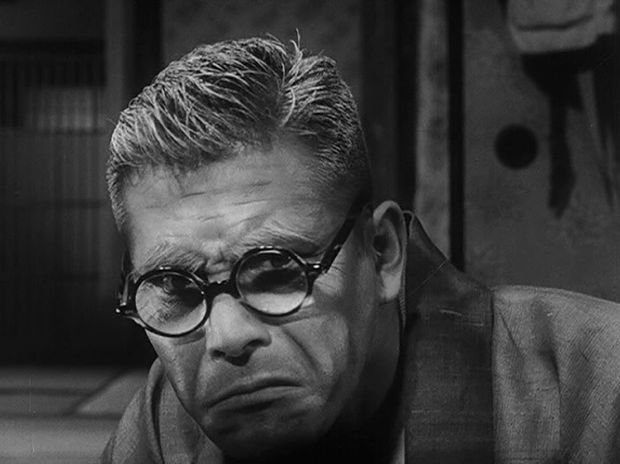

Their renunciation is dramatic. In Nakajima's case, the hero of I

Live in Fear (played by Toshiro Mifune [above] in effective old-age makeup),

an act of industrial sabotage becomes the desired route.

In the

Bergman character's case, it is her conscientious refusal to be

discharged from the hospital, a protest that she is able to carry off

insofar as her husband, played by the English actor Alexander Knox,

finally loses patience with her. In both cases, the renunciation of

the world is dramatic.

Europa '51 is scheduled to be shown on TCM this Friday afternoon,

August 6th, at 6 o'clock EST. I caught it early one Friday morning in

2006, taped it, then gave away the tape to a student, who kept it.

Damn! Needless to say, one is living for the sixth of August. I

believe you will like this movie.

Then go out and Netflix I Live in Fear, in its new Criterion

(Eclipse) edition. I think you will be amazed at the parallel. Oh,

and listen to the score of Fear, which is only heard during the

opening and closing credits. It's Godzilla-ish, with a theremin

front and center — if that's the right expression for a theremin —

and just breathes the . . . Atomic Age.

Endlich can I add a post-it to this post?

There's a line in T. S. Eliot's play The Family Reunion which sums up

these two movies, works of art, I think, just right. It goes like this:

In a world of fugitives, those going in the opposite direction appear to be running away.