There have been A-movie Westerns ever since the silent era — that is, prestige pictures meant to appeal to a wider audience than the usual one for Westerns, which consisted mainly of kids and grown-up males outside the big urban areas. The prestige Westerns were usually epics, like The Iron House, or The Covered Wagon or The Big Trail — films whose very size and scope branded them as out of the ordinary, worthy of consideration by all.

John Ford's Stagecoach, from 1939, was something else again. Neither a routine oater nor an epic, it was instead a drama set in the Old West with an unusual and compelling story, or series of interlocking stories, and complex, well-developed characters. It was a medium-scale Western for the mainstream audience.

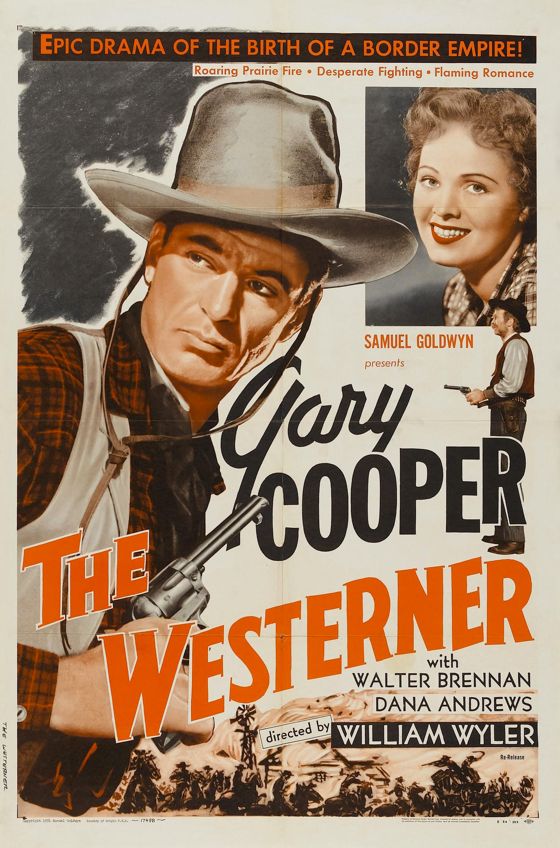

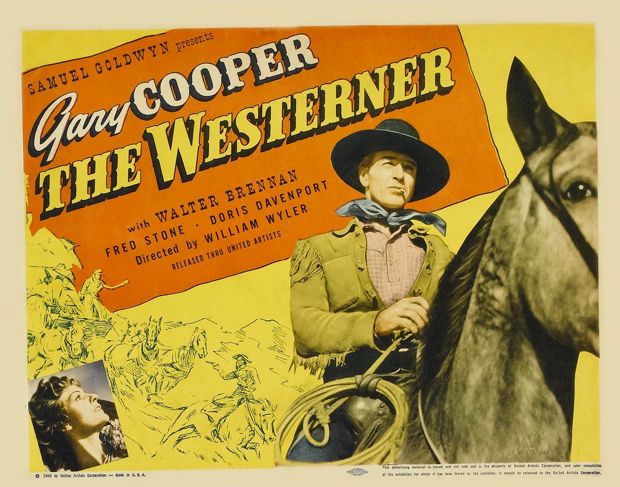

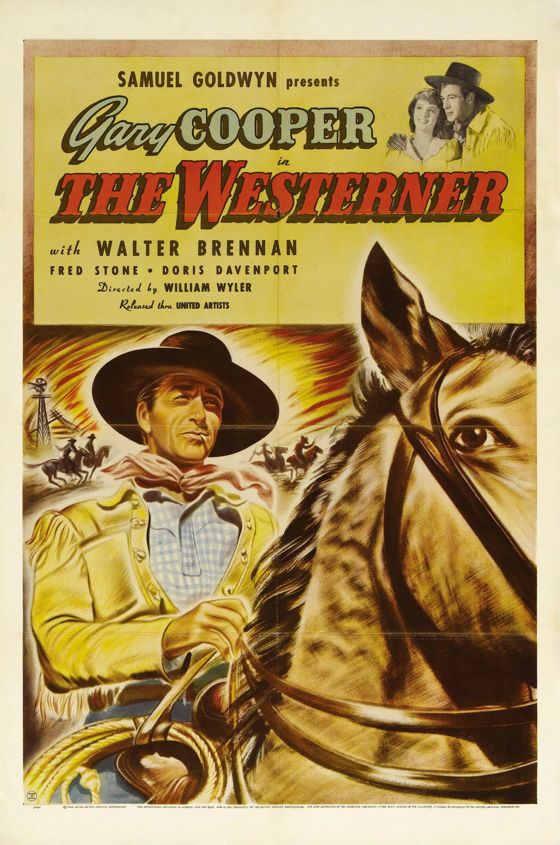

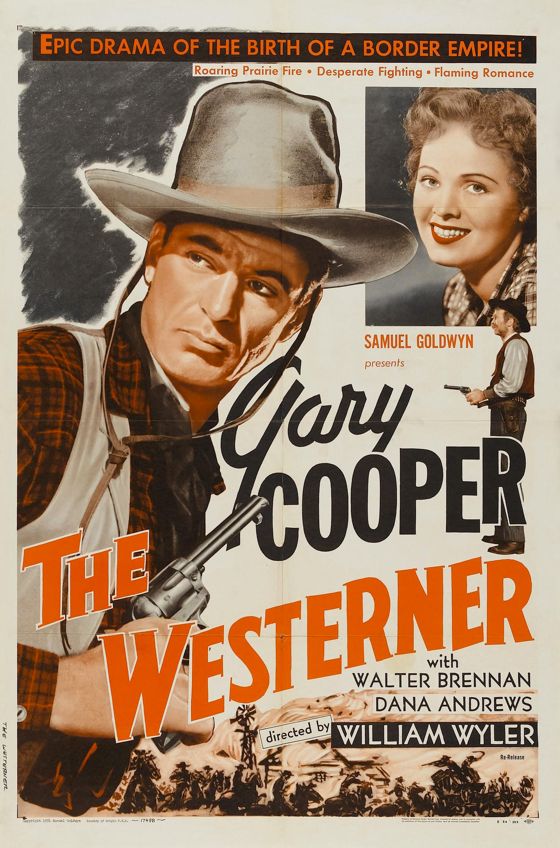

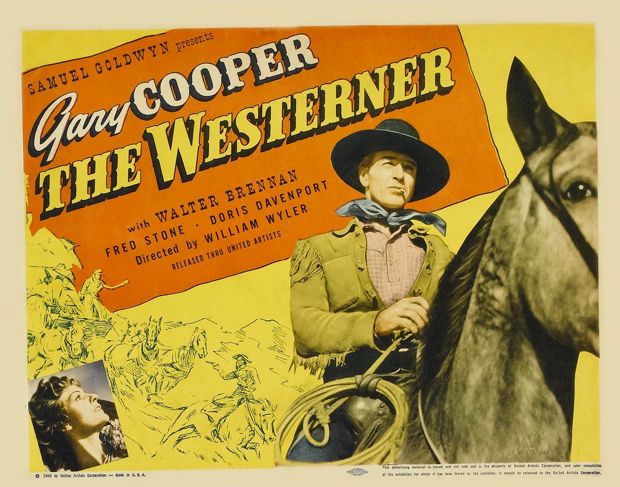

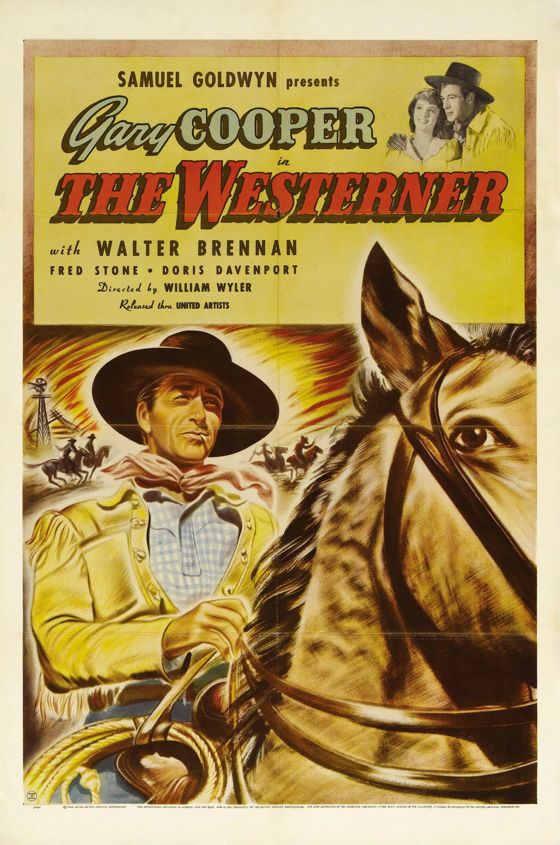

The success of Stagecoach inaugurated a new phase in John Ford's career as a director of Westerns and spawned more films like it — more medium-scale A-Movie Westerns . . . Westerns for everybody. One of the first of these to appear, just a year later, was William Wyler's The Westerner.

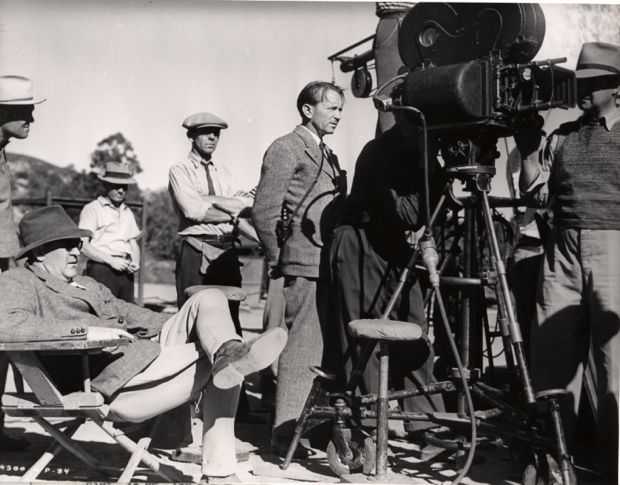

Wyler was a good choice to make a film in the Stagecoach mold. Like Ford, he'd earned his spurs as a director of two-reel Westerns at Universal during the silent era, so he knew the territory, and like Ford he'd moved up to more prestigious and sophisticated kinds of movies. He was thus well-equipped to tackle the more mature sort of Western that mainstream audiences seemed to want.

[Note — there are some plot spoilers below.]

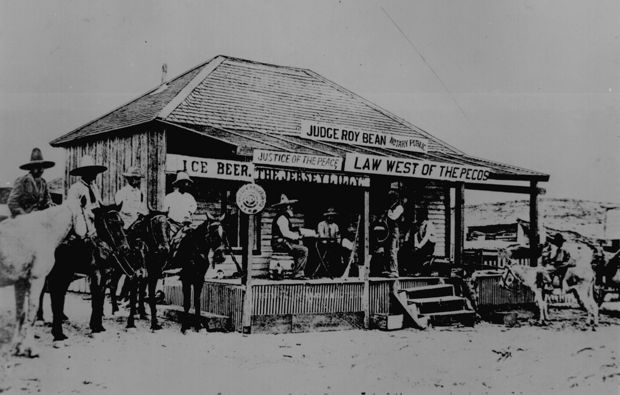

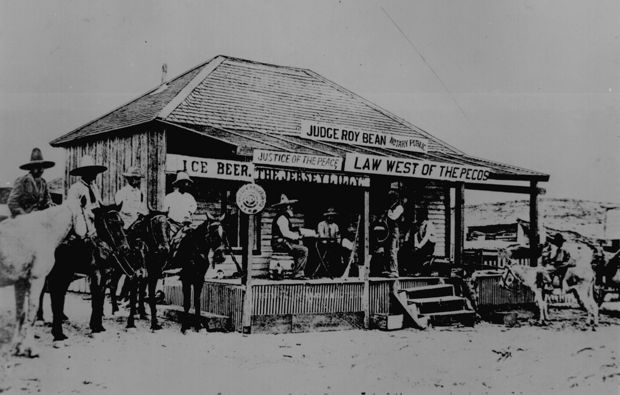

The Westerner was adapted from a story by Stuart M. Lake loosely based on the life of Judge Roy Bean, the legendary self-appointed judge in West Texas who like to call himself “the law west of the Pecos”. I've never read Lake's story, but screenwriters Jo Swerling and Niven Busch turned it into a wildly entertaining yarn about the notorious judge and a man in whom he finally meets his match, a drifter named Cole Harden. (Busch, who here collaborates on a fairly traditional, if up-scale Western, would later go on to have a strong influence on the noirish Westerns of the post-WWII era.)

Swerling and Busch dance a fine line between serious frontier drama, pitting cattlemen and farmers against each other in a classic conflict, and colorful character exposition, with the sort of laconic, rustic humor one finds in the best of Mark Twain. Bean, played masterfully by Walter Brennan in one of his finest performances, is a truly complicated villain — vicious, ruthless, funny and touching in an almost childlike way. Harden, played by Gary Cooper, is complicated as well, with a childlike quality, too, balanced by the iconic virility of his physical person.

These two men amuse each other, delight in outwitting each other, getting the jump on each other — they were born to be the best of pals . . . until Bean's sheer cussedness and meanness prompt a showdown. There's something tragic about the inevitability of this — it has the quality of a love story gone horribly wrong.

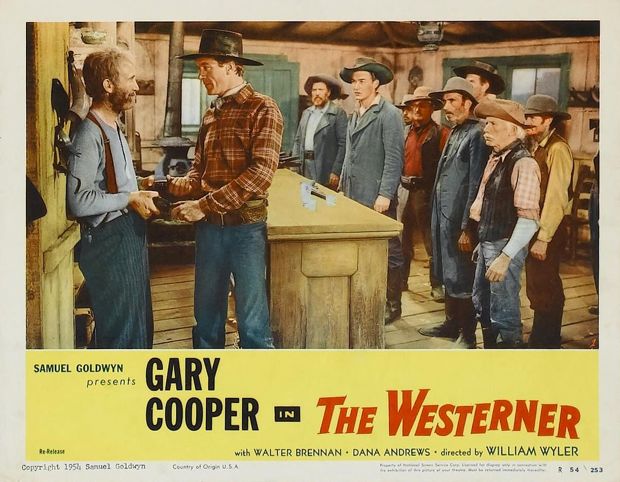

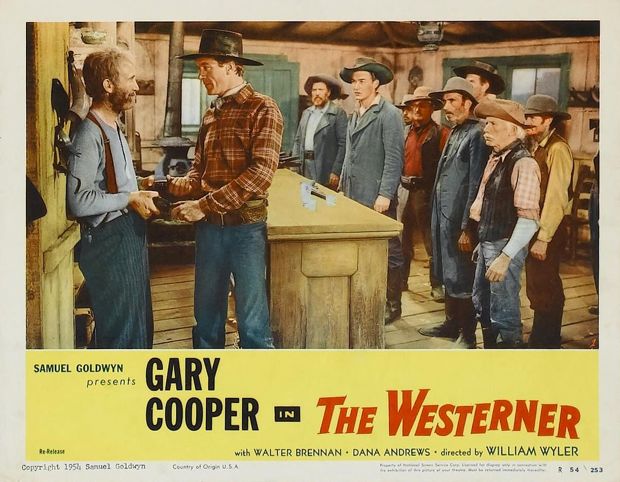

Like Stagecoach, The Westerner has long interior scenes in which displays of character take center stage. After an action opening, the film stays put for almost half an hour in Judge Bean's combination courthouse/saloon, as Harden tries to con his way out of getting hanged for stealing a horse. It's terrifically engaging stuff, because of the actors' magical incarnation of their roles and because of the genuine homespun wit of their dialogue.

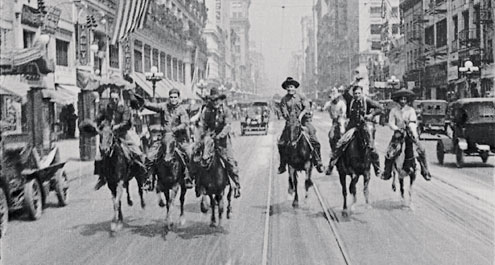

Wyler gives the traditional Western audience its thrills, too. The film has some of the most beautiful running inserts of galloping horses ever filmed — and a big part of the thrill of them is just watching Cooper ride. Cooper had worked as a cowboy and he knew how to sit a horse at a dead run with an uncanny grace few actors in the history of movies have ever matched.

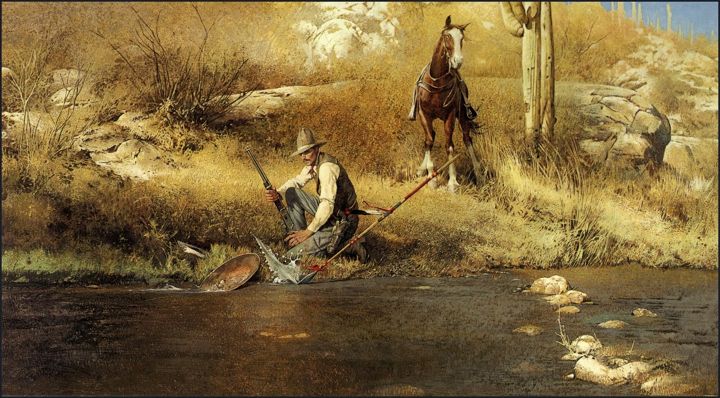

The film is magnificently shot by the great Gregg Toland, and magnificently designed — with a kind of romanticized grubbiness that reminds one of the work of Frederic Remington.

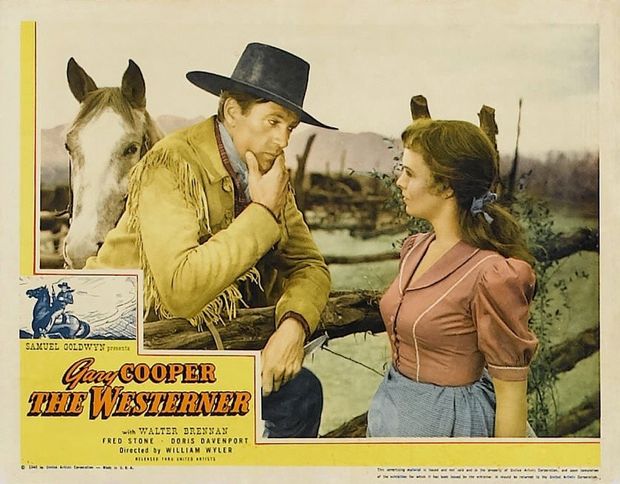

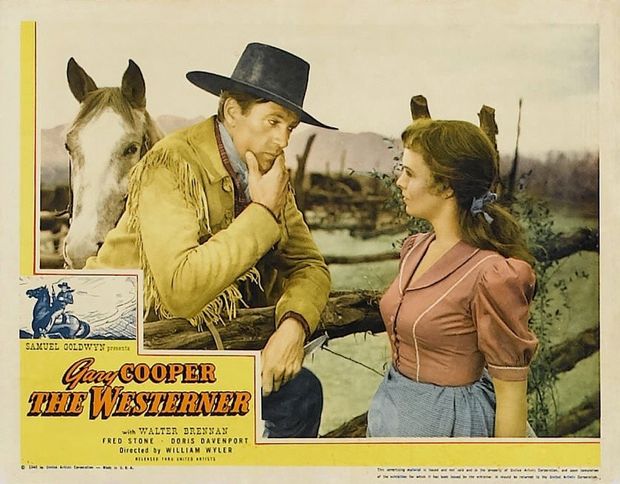

There's a love interest for Cooper, of course, with one of the women of the farm community, which helps motivate his conflict with Bean, who's on the side of the cattlemen, but it doesn't ignite many sparks. Cooper's winsome shyness with the lady gets stretched pretty thin by the final clinch, until it almost seems fey.

The film does make a stab at an epic dimension, presenting the feud between the pioneer groups as an episode in the making of Texas, and the nation — something the studio drew special attention to in the advertising. There's a big set-piece sequence showing the burning of the farmers' fields and homes that seems to have been meant to evoke the burning of Atlanta from Gone With the Wind, released the previous year. But much of the fire is done with process work, and Wyler doesn't appear to have had his heart in this part of the movie. He knew that the best thing he had to work with was the relationship between Bean and Harden.

Most unusually, the final shootout between the two men takes place in an empty frontier theater. The image makes sense here, though, because the heart of the film is men telling each other tales, hoodwinking each other, competing in the playing of roles. Its a vision of the Old West as a place in which a big part of life is the theatrical presentation of the self. Bean doesn't seem at all bothered that Harden gets the better of him in the end — he's played his part as well as he could, and the curtain always has to fall sometime. He and Harden still love and admire each other — but the show's closed.