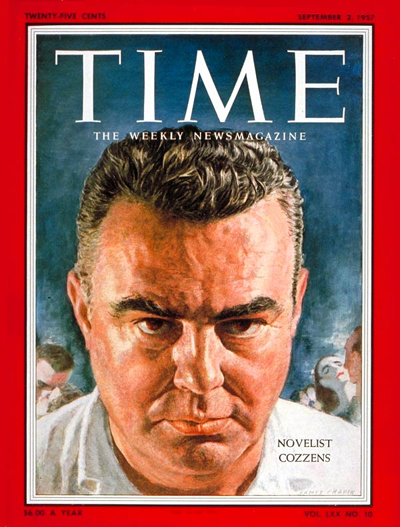

In Part One of this report, Paul Zahl, in pilgrimage mode, located, briefly viewed and photographed the former home of the late novelist James Gould Cozzens at the bottom of a hill outside Lambertville, New Jesrsey. Then he decided to go back up the hill in search of a man he'd been told might have some information about Cozzens during his time of residency in the area. Paul had been directed to this “man on the hill”, no fool as it turned out, quite by chance, by a woman he'd met who was out walking on the road that ran past the old Cozzens house. Here, in the pilgrim's own words, is a report of what ensued:

“A VOYAGE TO THE COUNTRY OF THE

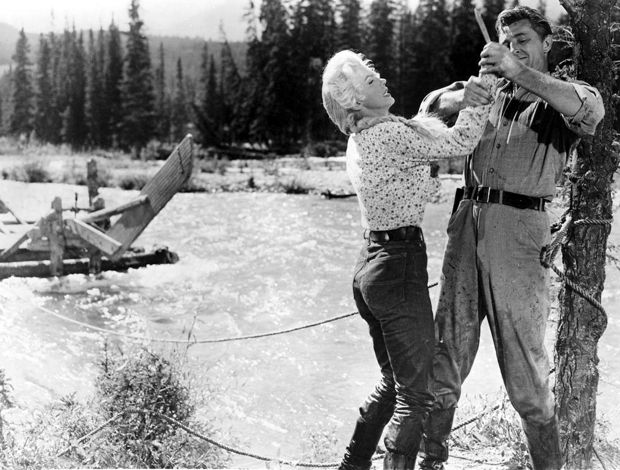

He was there in his house on the hill, and became a fund of information. We sat in his gazebo

— you couldn't help thinking of Marjorie Penrose and the scene in the

summer house, recreated well by John Sturges in the 1961 Hollywood

version of By Love Possessed — and he told me quite a bit. It turns out Cozzens was a

recluse, and kept completely to himself, though he was sometimes

spotted in town doing the shopping with a “short dark woman”. That was

Bernice Baumgarten, his wife, known in Cozzens's journals as “S”. My

new and welcoming acquaintance told me more, mainly about the

subsequent history of the house, and also the history of some well

known neighbors.

On the basis of “Bingo!”, I decided to drive down in to Lambertville

itself and take a look around.

That turned out to be a good decision. This is because Lambertville

leaps, simply leaps, out of the Cozzens novels. It is a smaller “Brocton” (By Love Possessed), a quieter “Childersburg” (The Just and

the Unjust).

I parked on a side street during a garden club tour of the old houses.

You can see the town “square”, presided over by a memorial to Civil War

dead, a bandstand, and an old mill. The Lambertville City Hall (being

nicely restored) [see the photograph at the head of this piece] is across the street, together with a spacious private

house that could stand in beautifully for “Brocton's” “Union League

Club”:

The Episcopal church is one block up the street, a little Gothic gem

that could use some exterior work:

There was a sadness incipient to

this old church building, a feeling shared by the stone cherub weeping

on the ground, just to the right of the main entrance to the church,

the entrance from which, as it were, Judge Lowe and Arthur Winner, Jr. in a scene from

who were ushering that Sunday morning, spied Colonel Minton rushing

over to the church to give them a piece of very bad news.

On the way out of town, I photographed a large and archetypal Victorian

mansion, now a retirement home, that is exactly the kind of house that

Cozzens describes on Greenwood Avenue in the same novel. It is just

such a building that becomes Arthur Winner's destination for his famous

— I think, epic — walk from the Detweiler house to his mother's,

during the final hour of Cozzens's sublime story:

About a mile further along, now beginning to approach “Carrs Farm”

again — Cozzens's old house, which I had found, Jumping Jehosaphat! and to which I was

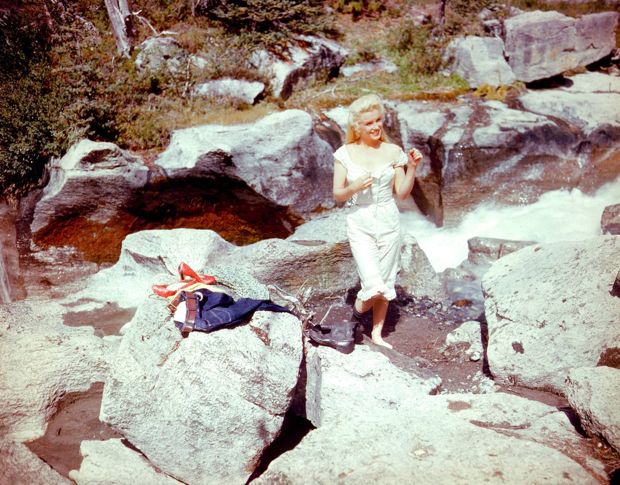

returning for a last look — the road suddenly turned into “Roylan”. “Roylan” is the section of homes outside “Brocton” where the doctors

and lawyers of the town in By Love Possessed have built their newer residences. “Roylan” is

envisaged well in Hollywood's version of the novel and is embodied today

right outside Lambertville:

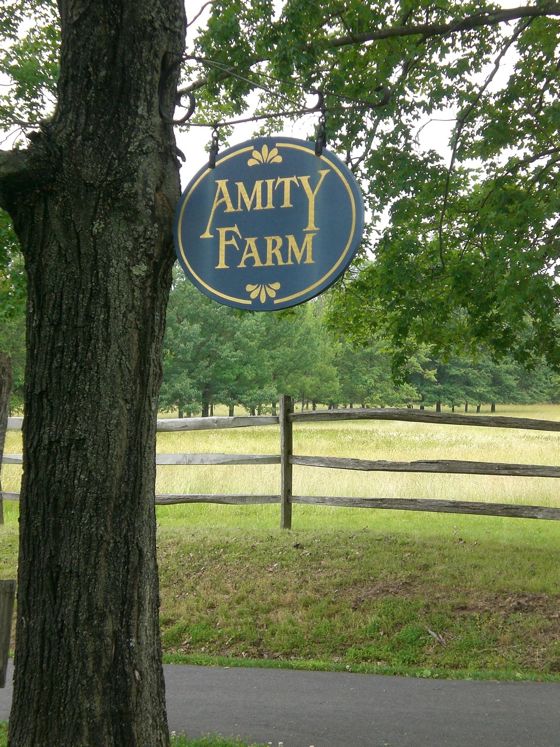

Then it was back down the hill to non-welcoming “Carrs Farm”. I

photographed the “Keep Out” signs, as well as a contrasting entrance

shingle to the farm across the road.

Two final notes concerning a successful pilgrimage. I didn't used to

believe in “karma”, and am still a little hesitant to use the term.

(This is for religious and even cultural sensibilities that are my

own.) But “karma” does express a little of what I felt reflecting on

those stark unmistakable “No Trespassing” signs. James Gould

Cozzens was a marvelous writer, and a greater thinker. He tells it

like it is, like it still is, like it always has been, and like it's

going to be be as long as human beings walk the earth. But he didn't

like them, human beings, and it showed in his life — a little less in

his work.

Whatever's going on at the end of Goat Hill Road — and that's no

business of mine, or probably anybody else's — the signal is

unchanged. The inspired “hermit of Lambertville” wasn't the only

one who wanted his privacy and solitude. The old place has not broken its spell.

On the other hand — and this I owe to my “walker” friend — another

detail came out. I told her that James Gould Cozzens was an avid

gardener, a serious student of roses. Who doesn't like a gardener?

She replied: “Well, that's interesting. Every year about this time I

always see a rose of uncommon beauty blooming along the fence in front

of Carrs Farm. It's not like any other rose I have ever seen. I say

to myself, why don't you pick it? After all, it comes back year after

year and is covered with vines and overgrowth anyway. Why don't you

pick it? (I never do.) But,” she continued, “I always wonder, where did

that rose come from?”

I made a left off of Goat Hill Road, under a huge electric pylon, by

the way, which would have caused Cozzens and his wife to move away in

exactly five minutes. They did, as it turned out, in 1958, after the

writer was done near to death by the “New York critics”, as he saw it.

But I turned homeward happy, happy that I had found Carrs Farm, and “Brocton”, and the story of Cozzens rambling rose.