A beautiful, sad, sweet image by Chris Ware . . .

Author Archives: Lloydville

THE HOUSE OF MYSTERY

STEPLADDERS!

They lurk in closets, utility rooms, sheds and garages — seemingly innocent, ordinary home implements . . . and yet they hold the potential for doom, sudden and ghastly.

Do we take the warning labels on them seriously? No! We laugh at them — until we tumble backwards into nightmare, into injuries, multiple, grievous injuries . . . or death!

CELEBRATING CARLA

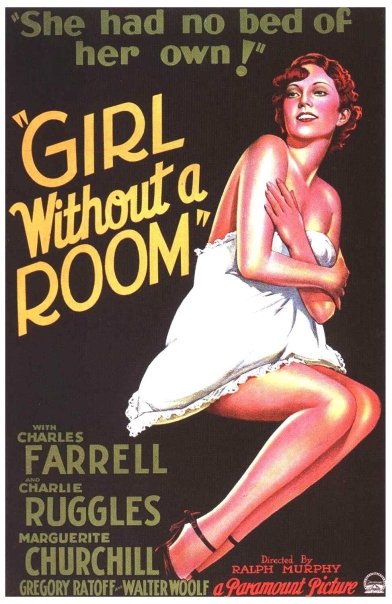

In a recent post I noted the 100th birthday of horror movie and Baja California icon Carla Laemmle. Imagine my delight and surprise when I heard from Scott MacQueen, a reader and friend of mardecortesbaja, that he knew the great lady and had hosted her birthday party in his own home, doing the cooking for it himself. (Scott's recipe for Beef Burgundy will appear on this site in the not too distant future, as soon as I have a chance to try it out in the world-famous mardecortesbaja test kitchen.)

Scott also sent along a picture of the festivities, above — with Carla flanked by David Skal (author of Hollywood Gothic) on the left and by Rick Atkins (co-author of Among the Rugged Peaks, Carla's biography) on the right. (Click on the titles of the books to buy them!)

Ms. Laemmle looks — there's just no other word for it — adorable.

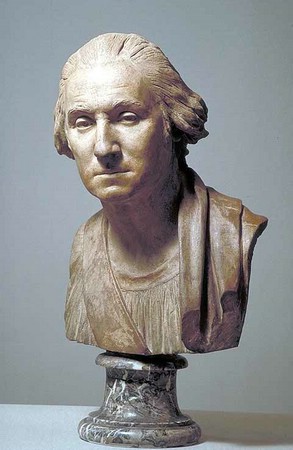

REPORT FROM PARIS: HOUDON

Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1848) was the greatest of French sculptors — indeed, one of the greatest of all sculptors. His marble portrait busts represent the pinnacle of his art, with their startling realism and feeling of life, deep psychological insight and sublime treatment of the marble itself.

He did famous portraits of most of the leaders of the Enlightenment and standing before these portraits today you feel yourself in the presence of these extraordinary men — closer than even their writings bring you. Voltaire's smile, Benjamin Franklin's genial intellect, Thomas Jefferson's emotional reserve are things you experience directly though Houdon's art. If I recall correctly, the portrait above is of an actress — her dramatic expression is not Houdon's but her own.

Franklin sent Houdon to America in 1785 to make a portrait of George Washington at Mount Vernon, where the hero of the American Revolution sat for a life mask and wet clay models, which became the basis for many subsequent commissions of busts and statues of the great man. In all of them, Washington looks both severe and modest, grand and simple — he could be a teamster or a king, which I guess made him such a perfect candidate for first President of the United States. His mystery, impenetrable even by his contemporaries, remains intact in Houdon's portrait.

My friend Coralie sent me the picture of the bust at the head of this report, which I think she took in the Louvre, from her iPhone just as her plane was about to take off from Paris for her return to Geneva. She said she wanted to share it in case the plane crashed. This makes perfect sense to me. With all of Houdon's portraits, you get a feeling they might change their expression, might leave the room, at any moment. Houdon's work doesn't seem to have been made for the ages, but in the now for the now, whenever that now might be. They have the immediacy of ancient Greek sculpture, of real life coursing through stone — pure miracle.

REPORT FROM PARIS: LE PETIT BAR

The mardecortesbaja sentimental tour of Paris continues . . .

Last night, the indefatigable Coralie had a drink at Le Petit Bar at the Ritz, where Hemingway liked to drink when he was staying at that sublime hotel. (When American troops entered Paris in 1944, Hemingway, a war correspondent, was in the vanguard and headed straight for the Ritz to liberate it — he then went to visit Picasso, to see if he was all right, and finding him out, left him a crate of grenades as a calling card.)

Coralie informs me that Le Petit Bar was originally the ladies' bar at the Ritz, when mixed drinking was frowned upon. Today, it is restored to what it looked like in Hemingway's time, with the addition of photographs of Papa on the walls, one of which, with the big fish, can be partially seen in her photograph above.

Cheers!

REPORT FROM PARIS: LE GRAND VÉFOUR

My friend Coralie had lunch today at Le Grand Véfour, and sends the picture above to prove it. Envy her!

The first “grand restaurant” in Paris, Le Grand Véfour opened in 1784 as the Café de Chartres. Napoleon is said to have dined there. In 1820 it was bought by Jean Véfour and renamed. Between then and 1905, when it closed for 42 years, every famous French person you've ever heard of, like Victor Hugo, and many you haven't heard of, dined there. It was reopened in 1948, and became a favorite hang-out of Colette, who lived nearby.

Its decor doesn't seem to have changed much since its Café de Chartres days — the food is more variable. From time to time it will lose its third Michelin star, then regain it. Each development in the ongoing drama is headline news in France.

Coralie describes the experience of dining there today as “'si raffiné'! C'est un pur moment esthétique.“

REPORT FROM PARIS: A MOVEABLE FEAST

Today, intrepid correspondent Coralie visited the Musée Grévin in Paris, a charming old 19th-Century establishment (founded in 1882) which features wax figures and other curiosities. She snapped the picture above of a Hemingway figure before heading off to the Brasserie Lipp, on the Boulevard St. Germain, to commune with Papa's spirit by having a meal he famously enjoyed there once (or twice) — filets de hareng pommes de terre a l'huile, suivi du cervelas rémoulade avec une bière blonde Lipp . . . which is to say, herring and potatoes in oil, followed by a dish consisting of a kind of German sausage with a celery root and Dijon mustard concoction on the side, all washed down with a blonde Lipp beer.

Hemingway told two stories about having this meal at Lipp. In one, he had just cashed the check for the first story he sold to an American magazine, and went off to celebrate by himself at Lipp. In the other, Sylvia Beach, who ran the famous bookstore Shakespeare & Co., said he was looking too thin and slipped him some money for a decent lunch. In both stories, he ate cervelas rémoulade at the venerable old brasserie.

It became, in any case, symbolic of his struggling years in Paris, about which he once wrote, “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.” Below, the first course of Hemingway's meal, as served to Coralie today:

I was not particularly young when I first went to Paris, nor struggling, but my memories of it follow me around all the same, and my friend Coralie has allowed me to inhabit them again vicariously but vividly, just as I once inhabited Hemingway's Paris vicariously and vividly by eating cervelas rémoulade one afternoon by myself at the Brasserie Lipp.

REPORT FROM PARIS: LA COUPOLE

A couple of hours ago my friend Coralie was sitting having a coffee and a petite meringue at La Coupole in Montparnasse. It's one of my favorite places in Paris, so she sent me a picture she took of it while she was there.

Opened in 1927, La Coupole has been restored more or less to its original splendor, when it was the largest brasserie in Paris and a hang-out between the world wars for artists, especially expatriate artists — everyone from Picasso to Hemingway. Fans of the McNally brothers' brasseries in New York will recognize at places like La Coupole where they got the inspiration for their decor.

When I first went to La Coupole in the 1980s, the service could be brusque if your accent wasn't quite right, but once I had dinner there alone and all that changed. French waiters have a tender regard for solitary diners, and treat them with an almost affectionate solicitude. Dining alone can be socially awkward for some, and French waiters understand this, so they work hard to make the solitary diner feel as though he or she is the most important client in the room. It is one of the many subtle graces that make French society so civilized, especially when food is involved.

REPORT FROM PARIS: LA DAME À LA LICORNE

My friend Coralie, who lives in Geneva, is making a visit to her hometown of Paris. She asked me what places in Paris I would visit if I went back there, and I said that I would very much like to see again the unicorn tapestries at the Musée de Cluny. This morning I got a message from her and the photo above sent from her iPhone as she was standing in the presence of the tapestries.

It's not the same as being there myself, of course, and no photograph can do justice to the deep colors of the tapestry threads and the texture of their woven surfaces . . . but I still feel as though I'm seeing them again through my friend's eyes, in something very close to real time.

It's a kind of miracle, isn't it — like the survival of the tapestries themselves?

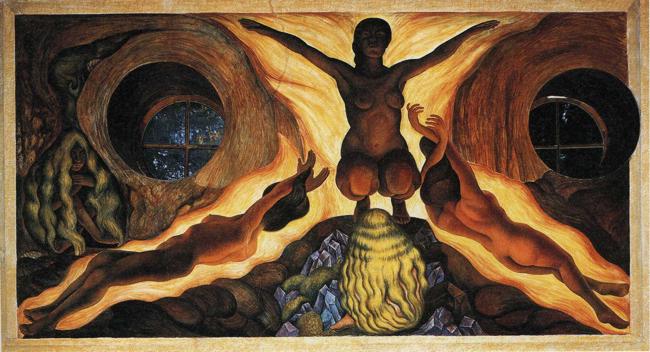

A DIEGO RIVERA FOR TODAY

Subterranean Forces, 1926-27

TROPICANA

In the 1950s, before Castro turned Cuba into a Marxist paradise, the Tropicana was the hottest (upscale) nightclub in Havana.

If you got a souvenir photograph taken of yourself at the club, it came in a folder with the cover depicted above. Back in Indiana, when you got home, you'd show it to all your friends, then put it in a drawer, then in a box stored in the attic, where it would be forgotten but slowly grow more magical with the years.

Eventually your grandchildren would throw it away, or dispose of it at a yard sale, in which case it might end up in the hands of a collector who would scan it and post the scan on the Internet, where it would become something to marvel at.

[With thanks to Arkiva Tropika, where you can find lots more images like this . . .]

OH, THE TRAGEDY OF IT ALL!

A BÉRAUD FOR TODAY

Jean Béraud left us the most charming records of the boulevards and cafés of Paris during the Belle Époque. The Impressionists often treated the same subjects, but their emphasis on the surfaces of their canvases, on effects of light and color, took precedence over documentary concerns. Béraud wanted us to know how it felt to physically inhabit the places he painted. Like all academic painters, he concentrated on the drama of space, as a way of drawing us imaginatively into his images.

The painting above depicts La Pâtisserie Gloppe on the Champs Élysées in 1889. Béraud evokes the magical use of mirrors in the shop's interior, the behavior of its patrons, the bourgeois ordinariness of the scene. It is rooted in the here and now, which has become the there and then, and so oddly poignant, in a way the Impressionists rarely are. Béraud recedes into his work, creating a space for us to enter this bygone moment of a bygone age.

The image has something of the authority of a photograph and something of the intense subjectivity of the artist's desire to record just what he saw, just what he thought we might have seen if we had been with him that day in the shop, and no more.

He has created a profoundly democratic work of art, radically out of step with the neo-Romantic egocentricity of the 20th-Century modernist.

REPULSIVE BUT RIGHT, ROMANTIC BUT WRONG: AN AESTHETIC DELUSION

Hundreds of years from now, when historians look back at the intellectual life of the 20th Century, I think they will be struck by two extraordinary, almost inconceivable delusions, one aesthetic and one political.

In this post I'll discuss the aesthetic delusion, which involved the violent reaction against the art of the Victorian age. The disillusionment with the European political structure brought on by the madness of WWI created a sense among intellectuals that all aspects of the 19th century world had been invalidated at a stroke. Modernism in the arts arose as a response to this, attended by great glamor and energy. It was primarily reactionary — the new forms it embraced rarely had value in themselves . . . their juice derived from the simple fact that they were not Victorian, were anti-Victorian.

Most of what had made art valuable as a cultural force — as an example of virtuosity, of discipline, of social community, of faith — was simply jettisoned. In their place was substituted “attitude”, the attitude of rebellion. The fine arts of the 20th Century instantly became irrelevant to the popular mind, finding a home in the esteem of an increasingly hermetic elite, dependent on institutional support for their survival.

The irony of this was little appreciated. The academic art of the 19th Century, against which the modernists rebelled, had depended on official endorsement, but also on the approval of a wide and diverse public. The “anti-academic” art of the new, permanent “avant-garde” had no life at all apart from the patronage of museums, institutes of “higher learning” and a gallery establishment catering to the very wealthy.

The old functions of art continued to be performed in areas outside the control of these elites, in the arts of film and popular music, for example — which is why film and popular music became the most exciting and dynamic art forms of the 20th century, even as what were formerly seen as “the fine arts” went on enacting their increasingly tiresome rituals of negation, carried to absurd extremes. Painting, we would eventually be told, was about nothing but paint.

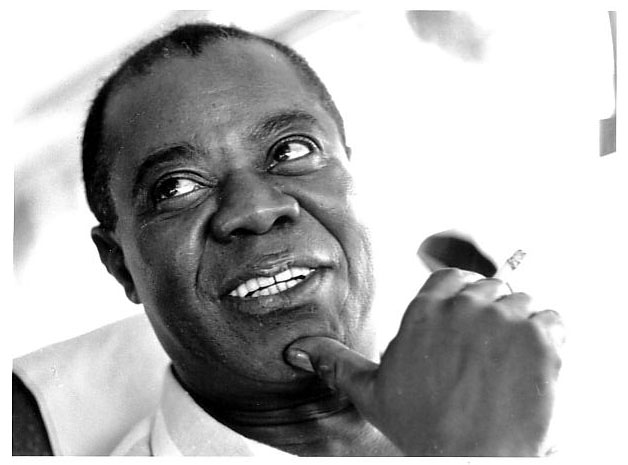

The establishment which once endorsed Victorian academic art, and by extension all traditional art, had become repulsive in the 20th Century. Those who sought to replace this art with “modern forms” became romantic. These labels acted as blinders, almost as blindfolds, until it became impossible to see that the reactionary gestures of the modernists had little content beyond the gestural, while those who toiled away in discredited or unsanctioned forms (like Mr. Armstrong, above) were creating the truly great, valuable and enduring art of their time.

In an upcoming post I'll have a look at the seminal political delusion of the 20th Century.