. . . from Naughty Town!

. . . from Naughty Town!

. . . with my sisters at Red Rock Canyon — shocking gossip is exchanged.

. . . in China!

. . . two crazy sisters rolling into town for New Year's.

Those were the days . . .

The Fortune Teller, 1594. The young woman, under the pretext of telling the young man's fortune, is attempting to steal his ring — but there seems to be much more going on in the picture than this.

Photo by Jae Song, Belize.

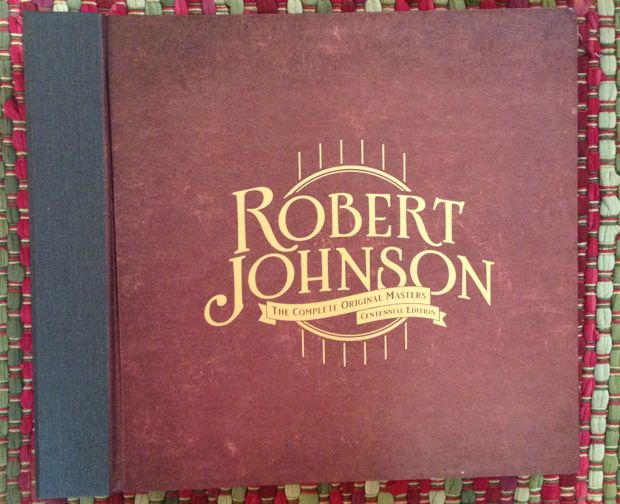

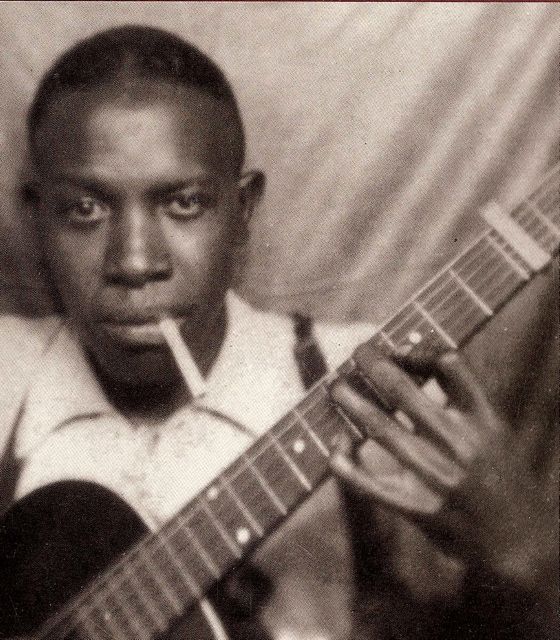

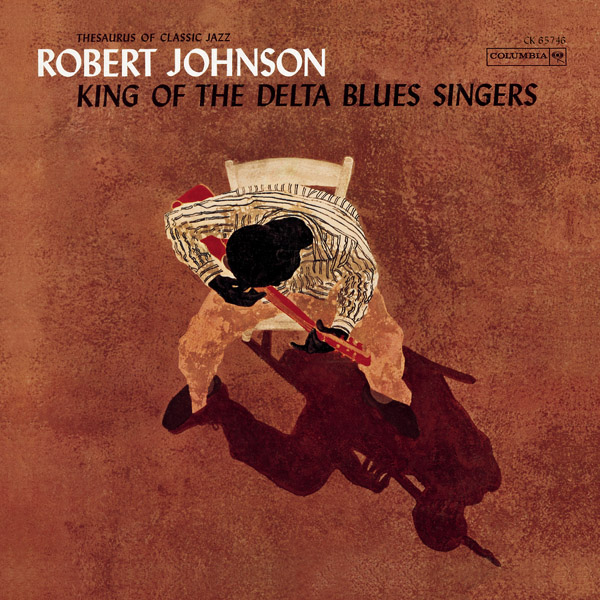

In honor of the centennial of Robert Johnson's birth this past May, Sony issued an amazing set of his works, on vinyl. Twelve ten-inch discs — the size of 78s but playing at 45rpm to accommodate modern equipment — reproduce all twelve of his records as originally released, twenty-four songs in all, complete with reproductions of the record labels.

The discs are packaged in a vintage-style 78 album — from which term we get the still-current designation for a single-disc LP or CD. The album comes with a CD of the new re-masters of Johnson's complete works (including the five outtakes not released on 78), a CD of related music and a DVD biography of the legendary bluesman.

I'm sorry that the set is so expensive — making it a kind of fetish object for Johnson worshipers, rather than the sort of thing that should be a part of every civilized American home, like a leather-bound set of the complete works of Shakespeare or Dickens, like a fine edition of The Bible. Johnson's work belongs in that company — as some of the greatest art ever produced in this country . . . as art that has helped define this country.

I went mad and bought it despite the price, and haven't regretted it. Pulling those discs out of sleeves and playing them on a turntable, just as they were originally made to be played, is a profound experience. This is partly due to the thrilling immediacy of the new re-masters, from which the commemorative vinyl was created. It may sound a bit processed to some ears, but there's no denying the startling presence of Johnson's voice and guitar, with all but the most minimal noise from the ancient discs eliminated.

It's partly due to the ritual of spinning the music on a turntable, putting you in touch with the earlier generations who first heard Johnson's music that way — the relatively few people who bought the original 78s, the musicians of the late Sixties and early Seventies, like Bob Dylan and Eric Clapton, who heard and were deeply influenced by the LP reissues.

Things are bad in America right now, politically, socially and economically. But anyone who's tempted to give up on the republic only needs to listen to the music of Robert Johnson to believe in America again. It's the best of what we have been — the best of what we might still be again.

Characters in popular art who make fun of sex, of their own sexuality, while still being deeply and powerfully sexy strike me as peculiarly American — I can't think of any examples that originated in other countries.

The English music hall created a kind of ditzy sexpot, best exemplified by Beatrice Lillie (above), but the ditzy sexpot had a very restricted erotic appeal — she tried to appear accidentally sexy, and was never sexually threatening in any way. That was her charm. The “naughty schoolgirl” figure crosses cultures, too, but her mask of good-natured innocence is just that — a mask, behind which to deliver erotic innuendo.

But America came up with something new — and as far as I can tell, Clara Bow was its first example. She was frankly, unabashedly sexual, often in a way that threatened buttoned-up men, but she had a way of laughing it all off as a lark — as something not to be taken too seriously.

You can see traces of this attitude in the great female blues singers of the early 20th Century, like Bessie Smith, but Smith knew that she was being bad — her tossed-off double-entendres had a leering quality, suggesting a down and dirty smirk.

Bow had none of this — to her there was nothing down and dirty about sex at all. It was just about having fun, and if it was the most important thing in life, that was only because having fun was the most important thing in life. Her overt but always skillful and imaginative flirtatiousness honored the game of flirtation, accepted it for what it was — if men didn't understand it, or know how to play it well, that was their problem. It gave her an advantage which she cheerfully exploited.

Bow was different from the wise-cracking females in screwball comedies, who played the game with an edge of cynicism, somewhat resenting men for their dull-wittedness, even if they ultimately forgave them for it. Stanwyck's character in The Lady Eve (above) is the paradigm for this type.

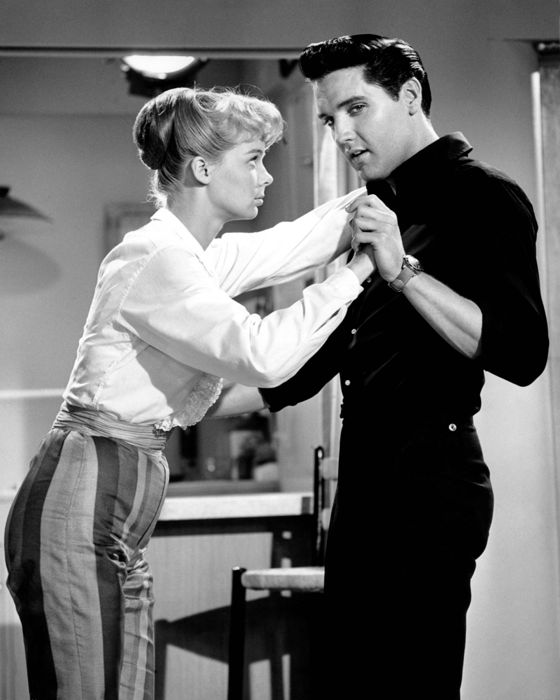

Bow's true successors in American culture were Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, who were sexy, knew they were sexy, laughed at their own sexiness while flaunting it without shame, in a state of paradoxically pure innocence about it.

They could be ironic but never, ever cynical.

The new DVD set Treasures From American Film Archives: The West has a stupendously good print of the silent film Mantrap (above) in which Bow definitively realized the new type of sexuality she pioneered. It's one of the greatest and most electrifying performances in the history of cinema, a performance that led to her being cast in It — to be seen as “The 'It' Girl”. They had to call it “It” in her case, because there was no existing word for what she had — no previous form of sex appeal applied. It was a new kind of it.

[I have never seen a still photograph of Bow that really captures her screen persona. The studio publicity photographers tried to fit her into familiar categories — glamor queen, vamp, flapper — none of which came close to evoking what she did on screen, which is hard to evoke in words, too. You just have to watch her best movies — she herself thought that Mantrap was the best of them all — and marvel.]

Although the first truly important narrative film made in America, The Great Train Robbery from 1903, was a Western of sorts, it took about five years before the Western-themed film resolved itself into a recognizable genre. It was a wild and wooly ride, which the form almost didn't survive. Like The Great Train Robbery, early Westerns focused on violent crimes. They modeled themselves on sensational Western dime novels and appealed mostly to kids and male working-class moviegoers — and to foreign audiences. When producers and distributors decided to court a higher class of clientele, including women, the Western came to seem unsavory, driving the better sort of folk away from the fancy new movie palaces that were gradually supplanting the storefront nickelodeon.

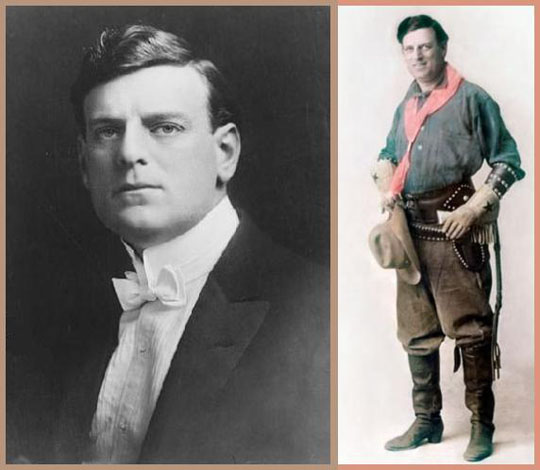

Gilbert “Bronco Billy” Anderson (above), who had played three bit parts in The Great Train Robbery, rode to the rescue by creating a Western hero who appealed to all classes and to women. “Bronco Billy” might start off as a bad man but his heart was always in the right place and he always ended up tamed by and defending conservative social values, usually personified by a beautiful and virtuous woman.

When Anderson lost interest in Westerns, and movies in general — his dream was to become a theatrical impresario — William S. Hart (above) was there to fill his boots. Hart played a tougher and more taciturn Western hero but like Anderson always came around to the defense of traditional values, religion and social order.

In the 1920s, an era of industry consolidation, the studios generally gave up on Westerns that might appeal to everyone. The B-Western was born, marketed once again to kids, to working-class males and to foreign audiences. These constituted a reliable though limited base for Westerns, which had to be cheap and formulaic to make money — but they made a lot of money on that basis and were a major source of studio profits. They produced big stars like Tom Mix, above, but stayed lean and mean where budgets were concerned.

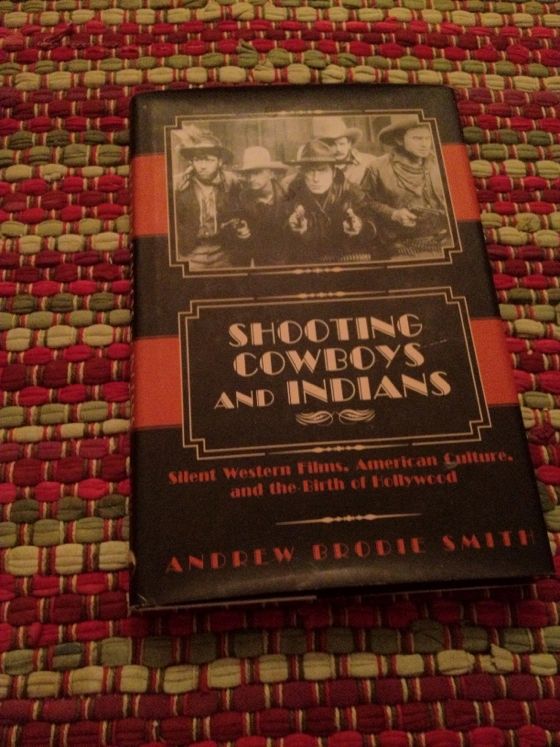

The wonderful book by Andrew Brodie Smith pictured at the head of this post tells the tale of how the Western was born and how it evolved into a genre — restricted in form by the 1920s but still vital and immensely valuable to the industry. Well-researched and written, it's essential to understanding the role and nature of Westerns in the earliest years of cinema.

[Photo © 2011 Huger Foote]

Tree, desert city.

Retour de Bal, 1879.

Not a successful outing, as outings go.

This summer — Lee and Nora at the Up the Creek Raw Bar, by the docks where the shrimp boats come in.