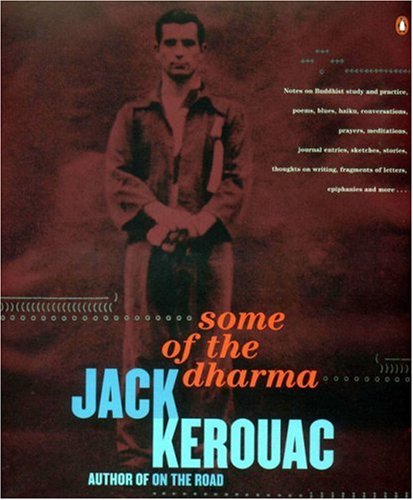

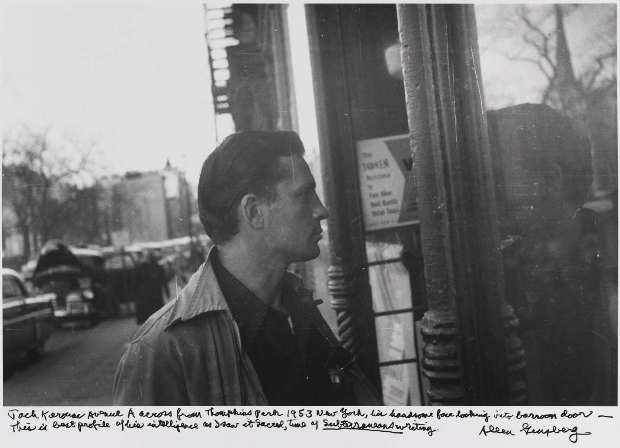

[Jack Kerouac, photograph with annotations by Allen Ginsberg]

I pulled into Nazareth, I was feelin' 'bout half past dead.

— Robbie Robertson

Paul Zahl and his wife Mary recently moved from Maryland to Florida.

On the road with a friend, hauling his belongings south, Paul had a

rendezvous with the Ghost of Christmas Past:

Our son Simeon says that faith is summed up in something he calls the

“Nazareth principle”. This refers to the question in the New Testament

where someone scoffs at Jesus the carpenter by asking, “Can anything

good come out of Nazareth?”

The idea was that Nazareth was a city, in the region of Galilee, which

was known for its “mixed-blood” and therefore suspect practice of

Judaism. Because the carpenter/prophet came from Nazareth, didn't that

disqualify him from being the real thing?

Yet as Simeon says, in life — time after time — the best things come

from the unlikeliest places. And this “Nazareth principle” extends to

the fact that out of trouble and wounds, disappointments and closed

doors, come often the actual breakthroughs of personal life.

I just saw this “Nazareth principle” up close and personal on a visit

to the town of Rocky Mount, North Carolina. A friend of mine and I

were driving a rental truck from Washington, D.C. to Orlando, Florida

and I decided to try to find and see a place I dearly love, in my

heart. This is the house where Jack Kerouac used to come at Christmas

during the mid-1950s in the midst of his wild ride of a life. Whether

Kerouac was in Manhattan, San Francisco, or Mexico City, he always

hitchhiked his way back home for Christmas. And home for Kerouac was

wherever his mother, “Memere”, was.

Because Kerouac's sister, Caroline, and her husband Paul, and their

little boy Paul were living in Rocky Mount for a period of years, home

for Christmas meant there.

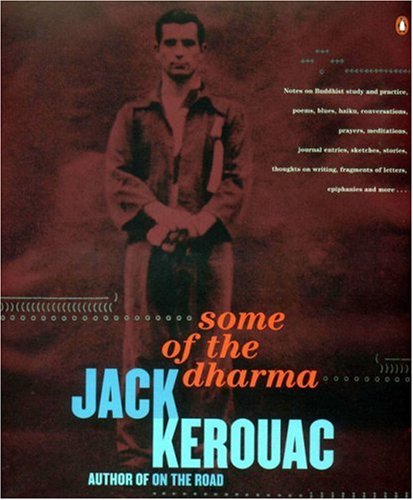

This was Kerouac's most intense Buddhist phase, which also meant a 24/7

dialogue with Christianity, his inherited religion. The weeks in Rocky

Mount are described in great detail in his notes on religion, which

were published posthumously as Some of the Dharma. Kerouac would

meditate almost every night in Twin Pine Grove behind his sister's

house, and write down every single word and vision that occurred to him.

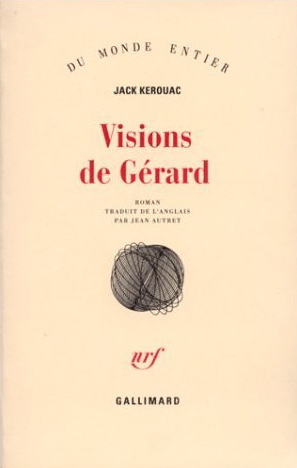

He also composed his book Visions of Gerard at the kitchen table in Rocky Mount.

So I wanted to see where these great words came to him, to “heav'n's

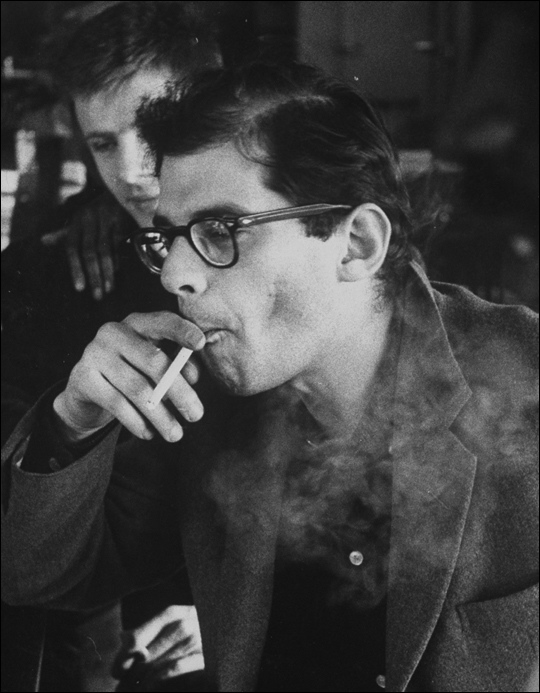

recording angel” — Allen Ginsberg's phrase for his friend Jack Kerouac. [Below, a very young Allen Ginsberg:]

But I had no address.

What I did have was a photograph of the house, taken by a local

journalist and published on her blog. I also knew that the house was

in a section of Rocky Mount about three miles outside of town which

used to be called Big Easonburg Woods but is now called West Mount. This

is all that my friend Michael McDowell and I had to go on — the name

for the neighborhood and a photograph of a tiny frame house painted

blue-gray with purple shutters.

So we pulled our Budget truck off Route 95 and made our way to a long

road called West Mount Drive, then just started driving and looking. There

were a lot of big trucks and no one had any patience with our little

moving van with its caution lights flashing. We drove about a mile and

saw several houses that might have been the one. And then . . .

[Photo © Marion Blackburn]

I saw it! The handicapped ramp and the colors exactly as in the photograph.

At the corner of Cameron Street and West Mount Drive sits the house in

which God spoke to Jack Kerouac. Or at least that is how I see it.

The jungled grove of pine trees is right behind the house, there is a

gas station just yards away (in Kerouac's day this was a “cracker”

country store as he described it), and a few small brick bungalows sit

on a dead-end road behind the home. They each have a satellite dish

and each one looks as if it were built in the mid-1960s.

I didn't dare to knock on the door — the house is obviously lived in,

with children's toys scattered in the small backyard — but asked about

it at the gas station. The man at the desk had never heard of

Kerouac. Yet this was definitely the house. I had read about it on

another Kerouac blog, in which the fan had found himself unwelcome when

he looked inside. But the pictures all matched.

[Photo © Daniel Barth]

We parked our truck, I walked around, meditated for five minutes — it

was about 100 degrees — and envisaged our man walking around with his

poncho and his dog between two a.m. and five a.m. on those cold

December and January nights in 1956. That the genius, like the Son of

Man, had “no place to lay his head” except for this tiny little spot in

the “back of beyond”, is simply an astonishing fact of human existence

and history.

I don't know if you've ever had the chance to read Visions of Gerard,

but it is sublime. It tells the story of the death of Jack's older

brother at age nine, in Lowell, Massachusetts — a kind of saint, this child. And

the author gives his tale and his interpretation of the tale absolutely

everything he has. It is a masterpiece that I recommend to everyone,

especially if religion interests you. On one page Jack is a

Samsara-diagnosing Buddhist; on another, a Crown of Thorns Christian, of

piercing conscience and intention. And he wrote the inspired little

book at the kitchen table of this house on West Mount Drive at the

corner of Cameron Street.

Later that night, Michael and I stopped at the house of friends in the

Low Country of South Carolina. It was and is one of that region's most

beautiful and soulful plantations, an ante-bellum house of exquisite

taste and proportions. We had a wonderful time, with lovely,

thoughtful people.

But I myself was still in Rocky Mount! How could it be that “God”/A

Higher Power/Karma/The Father of All could have set up a world in which

one of His finest and most gifted spirits would have no settled home

save this tiny refuge, covered now,

and even then, with the dust of passing trailers and trucks and “Dukes

of Hazard” Corvettes. Yet that's the way it really is. And there is

something to this affinity with a Man of Sorrows that struck me on

Monday afternoon, and definitely struck Kerouac even back then as he

wrote his notes in the Carolina dawn, which mirrors the facts of

suffering life.

Nowhere could the Nazareth principle be more concrete than in Rocky

Mount, North Carolina, off Wesleyan Boulevard on that long industrial road which

cuts through Big Easonburg Woods.

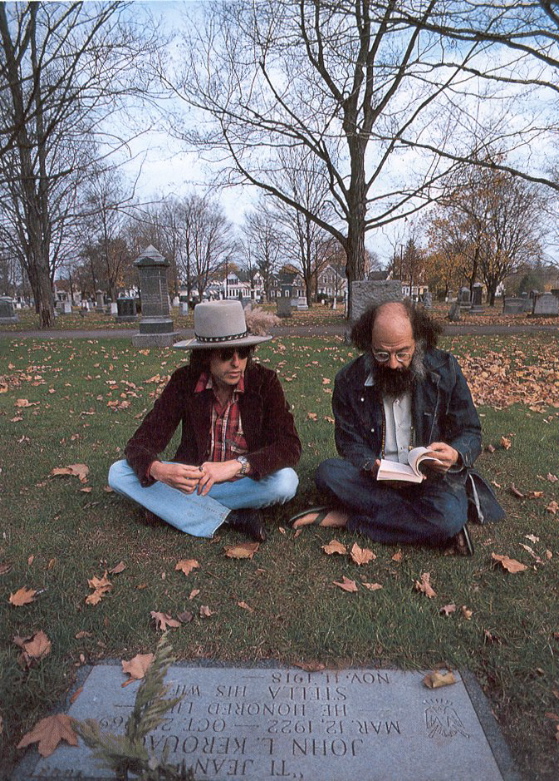

Jack Kerouac rests far from Rocky Mount, in Lowell, Massachusetts, where his grave (above) is also a place of pilgrimage, but you just know that his restless spirit is still on the road — that we're likely to encounter it anywhere, from Bodh Gaya to Nazareth to West Mount Drive.

[Note: Fans of Paul Zahl's contributions to this site can now find all his articles (and one about him) at The Zahl File, in the category list to the left.]