. . . in 1817, Confederate General Braxton Bragg was born.

. . . in 1895, the Lumière brothers exhibited their first film, Exit Of Workers From A Factory, before an invited audience.

. . . in 1941, the Grand Coulee Dam went into full operation.

. . . in 1817, Confederate General Braxton Bragg was born.

. . . in 1895, the Lumière brothers exhibited their first film, Exit Of Workers From A Factory, before an invited audience.

. . . in 1941, the Grand Coulee Dam went into full operation.

I'm happy to report that the author of the wonderful Femme Femme Femme site is in the process of switching hosts to avoid a shameful “Content Warning” unjustly appended to the site by Google, apparently as a result of complaints from unnamed viewers.

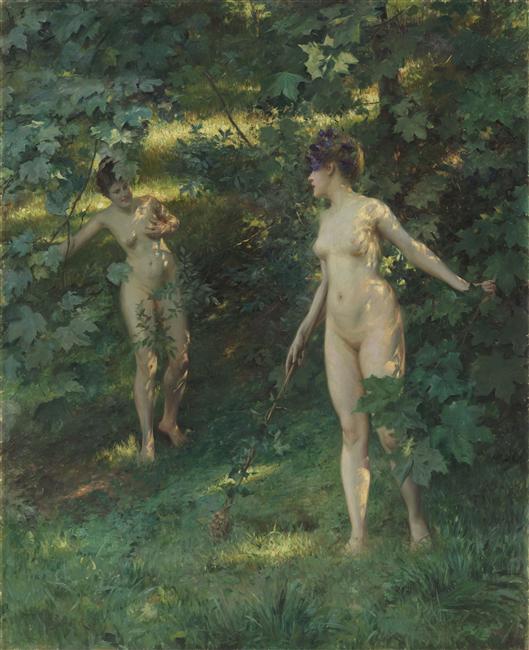

The site, as I've previously noted, posts images of women in art, including nudes, like the painting above, by Julius LeBlanc Stewart, but always with impeccable taste and discrimination. The idea that a few unhinged neurotics can force Google to label such a site “objectionable” is actually quite frightening. (Stewart's painting, incidentally, hangs in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris and has not to my knowledge inspired any widespread calls for its removal as an affront to public decency.)

Anyone who has a site hosted by Google should seriously consider switching to a different host immediately, as a protest, unless Google is willing to change its policy and apologize to the author of Femme Femme Femme. I know this would be a pain in the neck, but accepting Google's irrational policy might in the long run lead to an even greater pain in the neck, if a few kooks decide that your site is objectionable. So switch now if you possibly can and let Google know why you're switching.

Google, which has collaborated with the Internet censors of the totalitarian regime in China, has always argued that the Internet, in any form, will lead eventually to greater openness there. In fact, it seems to be leading to greater intolerance here.

The new Femme Femme Femme site, still under construction, can be accessed by following this link.

Natasha Richardson.

If as a general rule you assume that officers and representatives of large corporations are morally depraved you'll never go far wrong in your dealings with them. This is a bit different than saying such people are inclined to do bad things, since all of us are inclined to do bad things from time to time. Moral depravity is a special condition which results from inhabiting a mind-set and a culture in which self-interest takes precedence over all other considerations — in which no value is higher than advantage to oneself or to one's organization.

This is, of course, a definition of the condition of a sociopath. There is little point in judging or condemning a sociopath, because a sociopath has no conceptual tools for understanding the basis of such judgment or condemnation — and this can be baffling to those who do possess such conceptual tools. It makes the behavior of the sociopath hard to predict.

You might have thought, for example, that the officers at A. I. G responsible in large part for driving their company, and the world, to the brink of financial ruin might now be appalled at what they did — wracked with shame that their lunatic greed forced millions of American taxpayers less fortunate than themselves to fork over a portion of their personal wealth to bail out A. I. G., lest its failure precipitate a global catastrophe.

Instead, these officers feel that a portion of this taxpayer wealth should be awarded to them in the form of bonuses — a kind of reward for their irresponsibility and moral nihilism. This is how sociopaths reason — anything which benefits them is sensible and good. They are shocked, or at least terribly confused, when others question this principle.

Barack Obama doesn't seem to understand that reforming our financial system involves dealing with, anticipating the behavior of, sociopaths — perhaps because so many of his financial advisers are themselves products of the sociopathic culture of Wall Street.

He'd better wise up fast or we're all going to be in very deep trouble — even deeper than the trouble we're already in.

Stephen Colbert has sarcastically suggested that the American public needs to become a howling, pitchfork-wielding mob bent on taking the country back from companies like A. I. G. and the politicians who enable them. His suggestion is not without all merit. When the fate of your nation, when your children's future and your grandchildren's future rest in the hands of sociopaths, the option of armed rebellion shouldn't be taken off the table altogether.

One of the loveliest sites online is Femme Femme Femme — it's one I visit almost every day and which has been listed among my favorite links (to the right there) for a long time. It's a mostly visual blog that celebrates the female form in art with exceptional good taste.

On Monday, when visiting the site, I had to pass through a “Content Warning” message put up by Google, which hosts the site. Someone apparently complained that the site contained “objectionable” material. The image above (by Julius LeBlanc Stewart, from 1900) is about as “objectionable” as the site ever gets, if you think that paintings of naked women are objectionable, and if you do you should probably be in therapy.

Google in China has been a lapdog for that nation's totalitarian censors, and while it hasn't censored Femme Femme Femme it has kowtowed to the totalitarian sensibility by forcing the site's viewers to read and acknowledge what I can only describe as an unhealthy “opinion” about images of women in art.

That's objectionable.

I urge everyone to visit the site and send messages of support to its author — and if anyone knows how to complain to Google about its shameful behavior, please pass the information along.

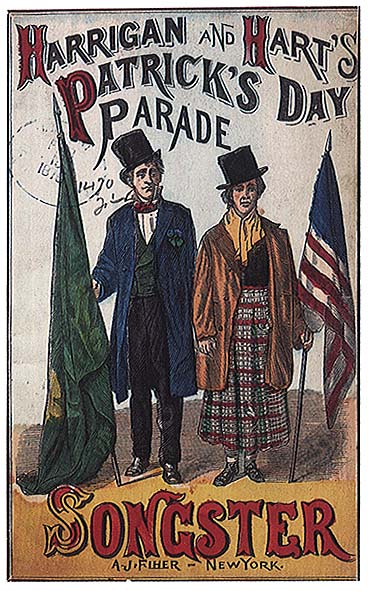

Before George M. Cohan, before Jerome Kern, there was Edward Harrigan. He wrote comedy sketches about immigrant life in New York City at the end of the 19th Century, later expanding them into full-length musical shows which became wildly popular. He and his partner from an earlier career in minstrelsy, Tony Hart, performed in the shows, for which Harrigan wrote the songs, with music by David Braham, sometimes called the American Offenbach.

The songs on their own were just as popular as the shows but aren't widely known today, which is a shame, since they're wonderful — sweet, tuneful evocations of working-class life in Manhattan when folks from all over the world crowded into urban ghettos and tried to figure out a way to live together, to be Americans together.

Mick Moloney has recorded a delightful collection of Harrigan and Braham songs, including their wonderfully cheerful “Patrick's Day Parade”. (You can buy Maloney's album here.)

“Patrick's Day Parade” moves me because it records the joy of people who were in their time so proud to be Irish and so proud to be Americans, and somehow saw no difference between the two kinds of pride. “We'll shout hurrah for Erin go bragh and all the Yankee nation!” We're unspeakably lucky to live in a country where such a paradox makes sense — where all of us can be proud to be Irish, even if our ancestors never set foot in the Emerald Isle. It's the kind of cultural

appropriation that's part of the miracle of America.

People have likened America to a melting pot, but it was never that — more like an Irish stew. The beef stayed beef and the potatoes stayed potatoes . . . it was the combination of disparate things that made the dish so satisfying, and still does.

So as one American to another — Erin go bragh! (Or, as Michael O'Donohue used to say, in the true spirit of Harrigan and Hart — Erin go bragh and panties!)

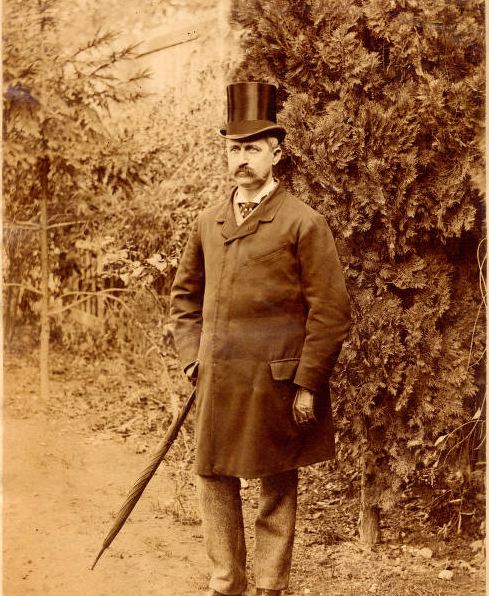

Nate Salsbury (above) started out in show business just after the Civil War as a singer, eventually forming a vocal group called The Troubadours, who performed in variety shows. Later he started writing full-length plays to feature his troupe. In 1879 he wrote a play called The Brook, a story of ordinary people at a picnic who entertain each other with songs and comic turns. It's considered to be a forerunner of the American musical comedy.

In 1882 he suggested to William F. (Buffalo Bill) Cody that they create an arena show about the wild west, an idea that wasn't new and that Buffalo Bill himself had been thinking about. When Salsbury said he wasn't ready to plunge into the venture immediately, Bill put together a show anyway. Its first season wasn't a flop but wasn't a big hit, either, and Bill convinced Salsbury to sign on as manager.

Together they created Buffalo Bill's Wild West, one of the great success stories of American show business and a cultural influence of almost immeasurable proportions. To Bill and Nate, however, it was just a show. Bill saw nothing odd about asking a theatrical impresario with stage experience to run it, Nate saw nothing odd about applying skills learned in playhouses to an outdoor spectacle involving horses and buffaloes.

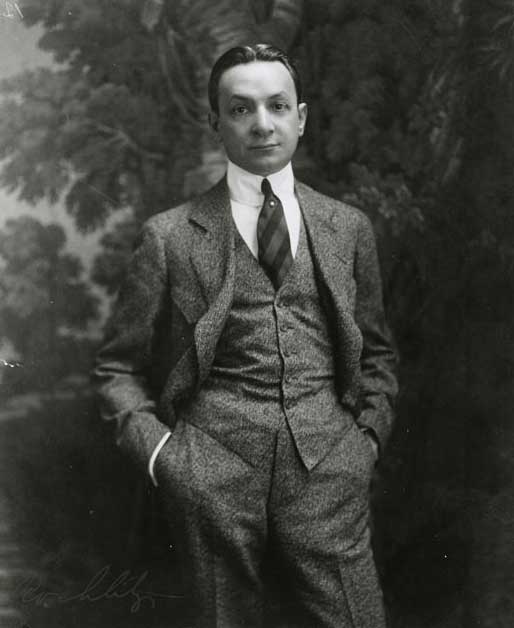

In 1893 Buffalo Bill's Wild West had a wildly successful run at an arena set up just outside the grounds of the world's fair in Chicago. A sixteen year-old kid named Florenz Ziegfeld (above) went to see it and was so enchanted that he ran off with the show when it left town, staying with it for six months until his father tracked him down and dragged him back home.

After years as a traveling impresario managing variety acts, Ziegfeld became a Broadway producer, inventing the Ziegfeld Follies, a kind of super-sized vaudeville show that featured headliners only, with more than a little burlesque thrown in for good measure, in the shapely and barely clad forms of the “Ziegfeld Girls”, chorines who did little more that parade around the stage looking beautiful.

The Wild West which had lured Salsbury away from Broadway set Ziegfeld off on a road that led him to prominence there — and eventually right back to a rendezvous with the destiny of the American musical, which Salsbury had helped inaugurate.

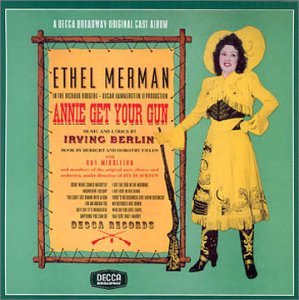

In 1927, Ziegfeld produced Kern and Hammerstein's Show Boat (above), perhaps the most important and influential production in the history of the American musical stage. Just about twenty years later, Irving Berlin, as part of the tradition of integrated book musicals that Show Boat inspired, collaborated on Annie Get Your Gun, a Broadway musical about Annie Oakley and her career with Buffalo Bill's Wild West.

Ziegfeld wouldn't have seen anything odd about this, any more than Salsbury, Cody, Kern, Hammerstein or Berlin would have. In Annie Get Your Gun, Buffalo Bill addresses a song to Annie that has become a show business anthem — “There's no business,” he sings to her, “like show business”.

Today, under the influence of academic specialization and the division of art into high-brow and low-brow categories, we see a great difference between “the Broadway stage” and, say, a circus, but earlier ages weren't bothered with such distinctions. They knew that — to paraphrase Rudyard Kipling — “All show business is one, man! One!”

A classic strip by George McManus, delightfully drawn and sometimes very funny.

The stories of women go unheard, I heard her to say, Lila.

“No one knows what happens to women. No one knows how bad it is, or how good it is, either. Women can’t talk — we know too much.”

From the short story “Ceil” by Harold Brodkey, published in The New Yorker, 1983.

[Image: “Venus Rising From the Sea — A Deception”, by Raphaelle Peale, 1822.]

Religiosity in 20th-Century art has been a problematic subject for mainstream intellectual critics, unless it could be given a negative twist, treated as a form of neurosis — Hitchcock's “Catholic guilt” being a prime example. This leaves many aspects of many artists' work unexamined.

mardecortesbaja welcomes ventures into problematic subjects and therefore presents without further ado a post about explicit religiosity in the films of Jerry Lewis, written by my friend and fellow film buff P. F. M. Zahl:

Jerry Lewis is often accused of sentimentality, of embarrassing sentimentality, in relation to the films he made in his classic period.

The sentimentality is in massive evidence within The Family Jewels (1965), in which a poor little rich girl who has been orphaned is required to choose her new 'father' from among her eccentric uncles. Lewis plays them all, or over-plays them all. Yet I defy you to not wipe away a tear at the conclusion of the movie, when the nature of her chosen 'father's' sacrificial love comes out. I defy you not to be moved. Even after you have winced through two hours of hammering slapstick.

The God question in Lewis is even more fraught than the question of his sentimentality. I'm not sure that even the French can handle this one.

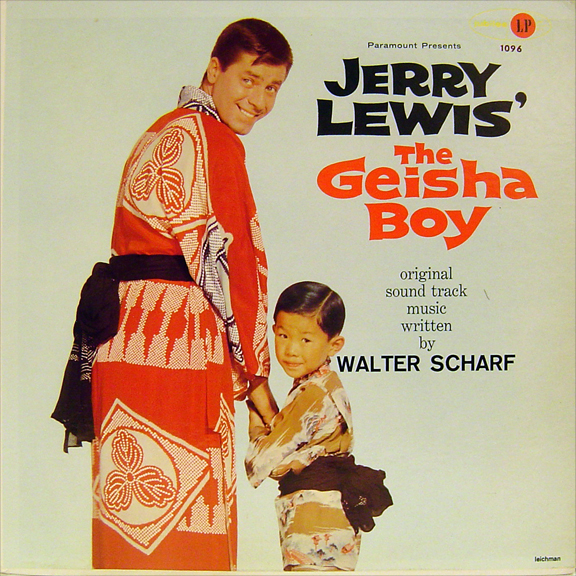

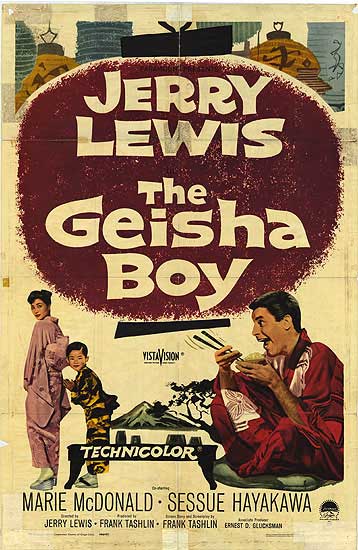

I am thinking of two of the main Jerry Lewis movies that were written and directed by Frank Tashlin. Tashlin, or “Tash”, as Lewis called him, taught his more famous student 'everything I ever learned' about movie-making, and then Jerry took it from there. But to much contemporary sensibility — today, that is — the God factor in two films, The Disorderly Orderly (above, 1964) and The Geisha Boy (1958) is just too hot to handle. And I am not even going to mention Who's Minding the Store? (1963), with its “We're Sorry” denouement written touchingly on the placards that all the lead characters wear as they plead for Jerry to forgive them. Nor will I mention Rock a Bye Baby (1958), with its soaring Grace on the part of the devastatingly unselfish TV repairman (Lewis) who brings up someone else's baby triplets alone.

In The Disorderly Orderly Jerry prays fervently for an old girlfriend, who did once spurn him and continues to spurn him, when she is brought into the emergency room after an almost successful attempt at suicide. Then when she recovers, Jerry prays again — and overdoes it a little — to God, thanking God for answering his prayer. He then proceeds to basically redeem this selfish but also hurt woman, winning her affection in a most 'Christian' manner, if I could put it that way. Every time I show The Disorderly Orderly to a group, the whole place dissolves at the end. And that's almost 50 years after it was made.

To be noted is Frank Tashlin's religion, which he by no means wore on his sleeve and would probably never have referred to. But we also know that “Tash” wrote and directed a short animated film for the Lutheran Church in 1949 entitled The Way of Peace, which is as explicit a Christian warning concerning nuclear war as ever was filmed during that era in Hollywood. This religious short subject had disappeared, and I had the privilege two years ago of bringing it back to the surface from the ELCA (i.e., Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) archives. I believe it can now be YouTubed. In any case, The Way of Peace is an important clue to Frank Tashlin's religious views. [Editor's note: I've written about The Way Of Peace previously, here.]

But it is The Geisha Boy where Jerry and God connect at the most length. Jerry stars as The Great Wooley, a magician on tour with the USO in occupied Japan. He charms a little boy whose parents are both dead and who has not smiled or laughed for five years. Jerry and little Mitsuo connect, and Mitsuo tells Jerry that he is the answer to his prayers. Jerry is moved, comments, and tells Suzanne Pleshette. Jerry then goes to Korea and performs for the GI's, taking time, in a sustained and extremely pointed scene, to pray before an altar — a sort of makeshift battlefield altar — for the little boy back in Japan. Prayer is referred to again, and finally The Great Wooley adopts the boy, takes him (together with his Japanese aunt, whom he marries) back to America, and all three become a happy family magic act. It is not actually all that maudlin.

As someone who believes in prayer, and who sure believes in reconciliation between previously estranged people, I find The Geisha Boy moving and also full of love. Plus, the Technicolor palette is out of sight, from the first shot to the last.

I would even go so far as to 'pair' The Geisha Boy with Kurosawa's Ikiru because they relate to the exact same period in the history of Japan, and in The Geisha Boy the little boy's last name is Watanabe; and as we all know, the hero of Ikiru is named Watanabe. In fact, the 'son' character in Ikiru is named Mitsuo Watanabe and the 'son' character in The Geisha Boy is named Mitsuo Watanabl. You can't convince me that Taslin hadn't seen Ikiru, especially when you hear Kurosawa report that it took them two full weeks to come up with the unusual 'Watanabe' name for the hero of that great classic of world cinema.

Jerry Lewis and God. Jerry Lewis and Frank Tashlin and God. Or maybe it was just the Fifties and early Sixties. But watch for God to appear within the Lewis canon. I also think He's still there, in the telethons. I see God pop up in the telethons all the time. I also know that Lewis, right in the heart of his heyday, treasured above all awards, above all European honors and medals, an award he received from the State of Israel. If you don't think God is friends with Jerry Lewis, then look again. Oh, and note the Buddhist tie-in, too, within The Geisha Boy, in the thumping importance given to the character of Harry the Hare. I don't think that's a coincidence either.

mardecortesbaja would just like to add that it's common, but hardly quite responsible, intellectually speaking, to admire Tashlin and Lewis for their radical dislocations of cinematic convention and their radical critiques of American society and to ignore the spiritual values (or the spiritual sentimentality, if you prefer) which also informs their work. You have ask, was the spiritual dimension an embarrassing aberration in that work, or one of the key sources of its radical attitudes? See my post on The Way Of Peace for further thoughts on this subject, especially as it relates to Tashlin.

The final panel from a Sunday page published in 1924.

Frank Borzage's The River is a turbid erotic fairytale about a boy-man and a “fallen woman” who awakens him sexually and is in turn saved by his innocence.

It's a film uncharacteristic of Hollywood in that its sensuality is both frank and serious — it takes adult sexuality as a given and presents it without the adolescent leer and snicker or the aura of the exotic which usually accompany erotic idylls in American cinema. In this film, Huck Finn meets Sadie Thompson at a dam construction site and learns about currents more treacherous than the Mississippi's.

The River stars Charles Farrell and Mary Duncan, who would be re-teamed a year later in Murnau's City Girl (above) — a very different kind of film, reviewed earlier here. Murnau, for all the poetic imagery in City Girl, was trying to create a more naturalistic atmosphere than he had in Sunrise — it was a break from his characteristic expressionism, an attempt to situate the story in a recognizably American context, as opposed to the mythic, vaguely European storybook environment of Sunrise.

The setting of The River isn't quite European but it's fantastic — the construction camp, with its tiers of workers' cabin jacked up on stilts on the side of a mountain, looks like something from Middle Earth. The narrative has a feverish, dreamlike tone which accords with its odd setting. One might link it to the home-grown American expressionism of Hawthorne and Poe, minus the high-Gothic spookiness.

Mary Duncan gives an extraordinary performance, as she does in City Girl — perfectly conveying a raunchy kind of lust mixed with cynicism mixed with a longing for something she can believe in. She's very sexy and very touching at the same time, much as Swanson was in Sadie Thompson. Farrell's mixture of naivete and virility is almost as impressive.

The plot of The River gets wildly melodramatic but the movie doesn't feel exactly like a melodrama — everything reads as metaphor, never to be taken quite literally. Farrell chopping down tall lumber to relieve his sexual frustration, nearly freezing to death in a snowstorm before Duncan's body heat restores him to life — it's all about sex and not much else.

Only one print of the film has survived and it's incomplete, missing a few early scenes and the whole last reel. The version on the recent Murnau, Borzage and Fox box set is a reconstruction using production stills and intertitles derived from the script to fill in the gaps. The loss of the last reel is very frustrating — one is desperate to know if Borzage was able to give the final action sequence the climactic excitement and release the tale demands.

We are left with a fragment (about half) of a minor masterpiece of the silent screen and one of the most original erotic reveries in all of cinema.

The penultimate panel from a Sunday page published in 1924 — final panel coming soon!

Matt Barry, over at The Art and Culture Of Movies, has just posted a superb appreciation of Jerry Lewis's films, pointing out the indisputable (and somewhat depressing) truth that they're still way ahead of their time . . . that modern movie comedies rarely evince half the daring and originality of the ones Lewis was making forty years ago.

The fifth panel from a Sunday page published in 1924 — curiouser and curiouser. Successive panels to follow!