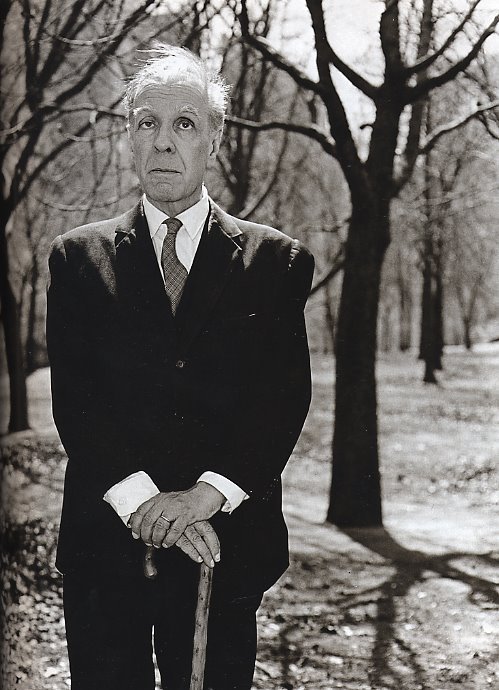

The instinctive is what counts in a

story. What the writer wants to say is the least important thing; the

most important is said through him or in spite of him.

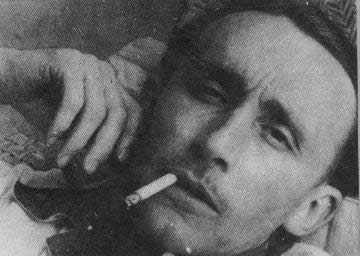

[Portrait of Borges by Diane Arbus.]

The instinctive is what counts in a

story. What the writer wants to say is the least important thing; the

most important is said through him or in spite of him.

[Portrait of Borges by Diane Arbus.]

P. T. Barnum’s circus went through a lot of configurations before he formed his final co-equal partnership with James Bailey. Bailey was an organization guy, Barnum was a ballyhoo guy, and between them they offered the public some dazzling shows, more complicated than any circuses which have survived into our own time, with the usual clowns and trapeze and juggling acts and exotic animals but also including exhibits of exotic people from around the world, including human freaks, and vast historical pageants, like “Nero”, staged by Imre Karalfy, complete with chariot races and the burning of Rome. All that and a musical donkey to boot.

In 1890, on a trip to London where he’d taken his great show, Barnum was recorded on an Edison cylinder. It’s scratchy and the words are hard to make out, but it’s still thrilling to hear the old showman’s actual voice.

One of the coolest sites on the Internet is The Big Picture, hosted by The Boston Globe. It offers high-resolution photographs of various newsworthy or human-interest subjects, and brings back the days of photojournalism as it used to be practiced by weekly magazines like Life and Look. Television seems to offer us a more comprehensive window onto the visual world than older media, but the fleeting nature of its images makes for a shallower experience most of the time. The stillness of a photograph continues to provide its own unique kind of revelation.

The Big Picture is always worth a visit.

The image above shows Vertie Hodge, 74, as she weeps during an Inauguration Day

party near Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. in Houston on Tuesday, 20 January 2009, after President Barack Obama delivered his inaugural speech. It's an AP/Houston-Chronicle photo by Mayra Beltran.

Is there anything sexier than a girl operating a 1955 Evinrude outboard motor?

I don't think so.

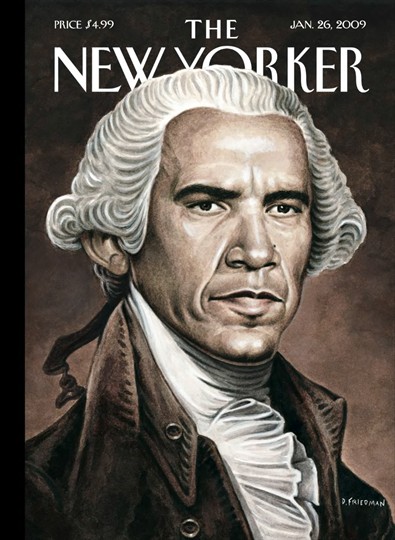

Our Washington correspondent, Dr. P. F. “Maleva” Zahl, was on the Mall in Washington yesterday with his wife and some friends to witness the Inauguration of the 44th President of the United States. The good doctor is my oldest friend — we met in seventh grade, in Washington, back when dinosaurs ruled the earth, and had many adventures in the very places shown on television yesterday, so he was in my thoughts as I watched the inauguration coverage. He was kind enough to send this special report of the day:

by Paul Zahl

[Correspondent Zahl stands on the left, next to his wife Mary with friends.]

We also see in Barack Obama something

that our little Episcopal Church culture wars never produced, neither

from the Left nor from the Right: a statesman, who listens without condescension, i.e.,

with felt interest and even sympathy, to those with whom he disagrees.

If only our own context professionally, which is a denomination of

Christians in 21st Century America, had produced a person like this man

seems to us to be. If only that, we would not be, with many, many of

our old friends and colleagues, in a broken, split, and bitter

aftermath.

Deo gratias.

A painting by Andrew Wyeth, who died today. He and Norman Rockwell kept the art of painting alive in a barbaric age.

A “carry” is a rocky part of a stream where one's canoe needs to be portaged to smoother water. From the rocks Wyeth looked downstream, towards a bend he couldn't see around. We can be pretty sure, though, that he's there now, on his way to the sea.

Many people are terrified of clowns. This photo helps explain why.

It’s from 1949, and part of a wonderful flikr stream of vintage photos by Charles Cushman, posted by Fun House, whose other flikr streams are also delightful. (Via Boing Boing.)

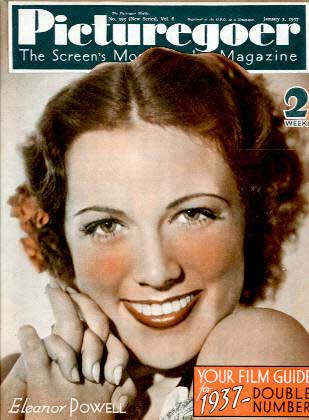

All films are about the theater, there is no other subject.

— Jacques Rivette

This provocative statement may need some interpretation or qualification, but it is essentially true and crystallizes the secret of cinema. All great cinema tries to supply what it lacks in relationship to theater — a visceral sense of physical space, the quality of tension in a live performance. It cannot actually supply these things, of course, but in trying to it stretches its resources to the maximum — in trying to be something it's not, it becomes itself more completely.

André Bazin wrote two brilliant essays on this subject, part of his argument in favor of mise en scêne as opposed to montage as the primal method of cinema. His insights have still not been wholly absorbed by film critics, but all great film directors have understood them, if only instinctively.

We may still be amazed that certain of the greatest directors have moved from work in the theater to work in film and displayed an instantaneous and absolute mastery of the latter medium. Orson Welles's first film, for example, Citizen Kane, is still considered one of the finest of all movies, and yet it was done without any significant term of apprenticeship in cinema. Vincente Minelli's first film, Cabin In the Sky, displays a similar mastery of cinematic form and style. His third film, Meet Me In St. Louis, is one of the greatest films ever made. Minnelli, like Welles, moved more or less directly from theater work to movies.

Both Welles and Minnelli wanted to create on film the same excitement they found in theatrical productions, and they both used cinematic techniques in bold and innovative ways to replicate that excitement. They are recognized as two of the most “cinematic” filmmakers, but that's just a way of saying that they were two of the most theatrical filmmakers.

Cinema can do many non-theatrical or anti-theatrical things — it can create interesting graphic designs, it can bombard us with spatially incoherent images — but no one has managed to create great art out of these techniques, despite the claims of the cinematic avant garde. It is only when cinema uses its most theatrical techniques that it is capable of genuine aesthetic grandeur.

One can speculate about why this is, but I suspect it has something to do with the primal significance of the theatrical experience, as it relates to ceremony and ritual. We dream in theatrical terms, creating coherent spaces in the imagination in which incidents unfold in dramatic time — as in dreams of pursuit, for example. We could dream in flat graphic images, or in a succession of unrelated or abstractly related images, but we don't. The imaginative rehearsal of emotion seems to require the spatial and chronological coherence of a theatrical environment.

The one exception to this rule among all the other arts is music. Though it's undoubtedly true that music as an advanced art evolved out of theatrical practice, out of ceremony and ritual, it seems to have an aspect more primal than that, perhaps originating in the rhythmic soothing of an infant. Throughout all cultural history music has been a vital adjunct to theatrical practice, but it has a hold on us which exists apart from the theatrical realm, strictly considered.

Considering the matter less strictly, though, one could say that all music involves performance of one sort or another, within certain set parameters of time, and so is essentially theatrical in nature — that music always, on some level, creates, signals and consecrates a theatrical moment, a theatrical space.

Cruel and unrelenting!

I can't move! I can't think . . .

. . . and yet, miraculously, none of this has managed to dampen my holiday spirits in the slightest, as the gay and festive portrait above will readily attest.

Next year most of us will be following the jalapeño crops in Mexico, sleeping rough and singing the songs of the land, so tonight it's only right to party like it's 1929.

Don't bring a frown to old Broadway,

You've got to clown on Broadway . . .

My friend Jae's cell phone can take panoramic pictures, like the one above of myself and our pal John hanging out at a bar in the Venetian, resting up from a grueling poker session.

[Warning: If you haven't seen Sunrise, don't read this — instead go

see Sunrise immediately.]

Sunrise may not be the greatest film ever made — it may not even be

the greatest film of the silent era — but it certainly has passages,

many passages, that rank among the greatest in the history cinema and

still help chart the limits of what the medium can do.

Oddly, though, most of these supremely great passages happen in the

first 45 minutes of the film. After that, there are many wonderful

moments, much gorgeous lighting and many striking plastic effects, but

none of them are breathtaking in the way the high points of the first

half are.

I think there's a fairly simple explanation for this, and it has to do

with the structure of the story itself. The film tells the tale of a

simple man living in a rustic farming and fishing village who's seduced

away from his wife by a vamp visiting the village from the city. He

determines to drown his wife in the course of a boat outing but when he

moves to do so he sees himself, sees what he's become, in her terrified

eyes and draws back from the deed. She flees him when they get to land

again, jumps on a trolley — he jumps on, too, and they ride into the

city. There, as he's trying to atone for his awful behavior, they

stumble on a wedding. The man falls apart, begs for forgiveness, is

forgiven, and they walk out of the church like a newly married couple.

This is the artistic, emotional and spiritual climax of the film . . .

but the film is only half over.

We then see the couple recover their former lightheartedness at a

fairgrounds. We cut back to the scheming vamp in the village, and this

sets up an expectation that she will somehow intervene in the couple's

reunion and jeopardize it — but in fact this never happens. The man

has made his choice — the vamp has no more power over him.

On the boat ride home a storm washes the couple overboard, the man

thinks his wife has drowned, and he's devastated. There's great irony

in this, of course, but no great dramatic weight, because it doesn't

involve any further development of the characters' inner lives. The

storm is a mechanical contrivance — an impersonal threat to a marriage

that has already been reborn and renewed.

The man rejects the vamp with physical violence, almost killing her,

before being told that his wife has been found alive — saved by a

bundle of reeds the vamp had gathered as a device for the man to use to save

himself after he'd killed the wife. Again, there are multiple

ironies in these developments but, again, no real progression in the

inner lives of the characters. The storm isn't a direct consequence of

the man's past behavior and the reeds don't redeem the vamp — they are

like visual and narrative puns with no fundamental significance for the

basic drama.

The second half of the film does contains things one would miss if Sunrise had ended at the halfway point. In the fairgrounds

carousing, Janet Gaynor's character gets to reveal herself as a sensual

being, something she isn't really able to do as the long-suffering wife

in the opening sequences, where her astonishingly bad helmet-wig seems

to be giving her a headache — as it gives us one. The George O'Brien

character is so frankly sensual, even when he's menacing, that there

would be an imbalance without those fairgrounds scenes. O'Brien's

character also suffers in the second half from the apparent loss of his

wife, a tragedy he almost brought upon himself. Without seeing that

suffering, we might feel that he'd gotten off too easily for his

despicable behavior. And of course the vamp gets her comeuppance —

though it's almost more comeuppance than she deserves.

But none of these things transcends the emotional and dramatic climax

of the scene in the church or adds anything of essential significance

to it. They're like echoes of and reflections on a story that's

already been told. In the second half, Murnau can't summon up sublime

cinematic expressions for powerful emotional developments — because

those developments simply aren't there.

Pointing out the flaws in the dramatic structure of Sunrise does

nothing, of course, to diminish its stature as one of the most

important works in the history of cinema. It was the film that taught

John Ford the secret of movies, and that alone would make it a work of

inestimable value. It's one of those rare films that one one can watch

again and again with increasing astonishment and enchantment, and it

continues to inspire each new generation of filmmakers, especially

cinematographers, for whom it is a kind of touchstone. But recognizing

its structural flaws might help explain the vague and perhaps even

guilty feeling of disappointment which steals over one whenever that

“Finis” card comes up on the screen.

The great passages of the film, great as they are, don't add up to a

great whole work.

[Vincente Minnelli's fine film The Clock has a couple of intriguing echoes of Sunrise, which I think are too close to be accidental. Both films deal with moments of crisis in a marriage that play out in an urban setting. In both movies, the crisis is at first exacerbated and then transcended by the city environment, which becomes a kind of character in the drama. In the aftermath of both crises, the married couples try to get back to a state of normality in a restaurant, but the simple act of trying to share a meal only emphasizes the distance between them. In both restaurant scenes, the women break down. These scenes are followed by ones in which the couples happen upon a wedding in a church — they enter the church and participate vicariously in the ceremony, which restores their sense of commitment to each other. In each film, the church scene is the emotional climax of the story. In The Clock, the rest of the film is coda — in Sunrise the rest of the film is coda, too, but stretched out far too long, and too loaded with incident, to work properly as such.]