The circus was a fixture of American popular entertainment as early as the colonial era. It competed vigorously with fancier forms of theatrical entertainment in the first decades of the 19th Century and survives in several forms today. It was always evolving — the only constant being the “circus”, the ring, which for most of circus history existed primarily for a horse or horses to race around.

In the early 19th Century, if you had a clever horse and a tent, you had a circus — all the rest was filler on the bill.

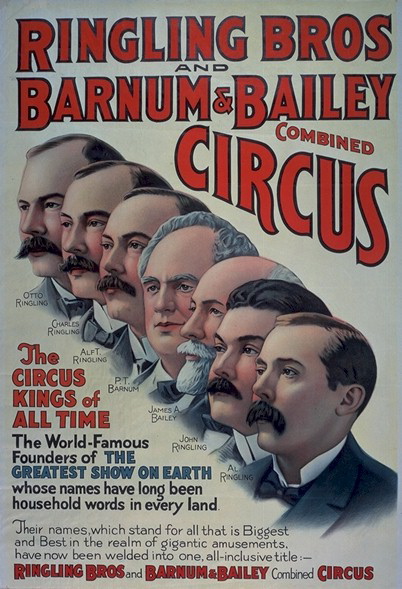

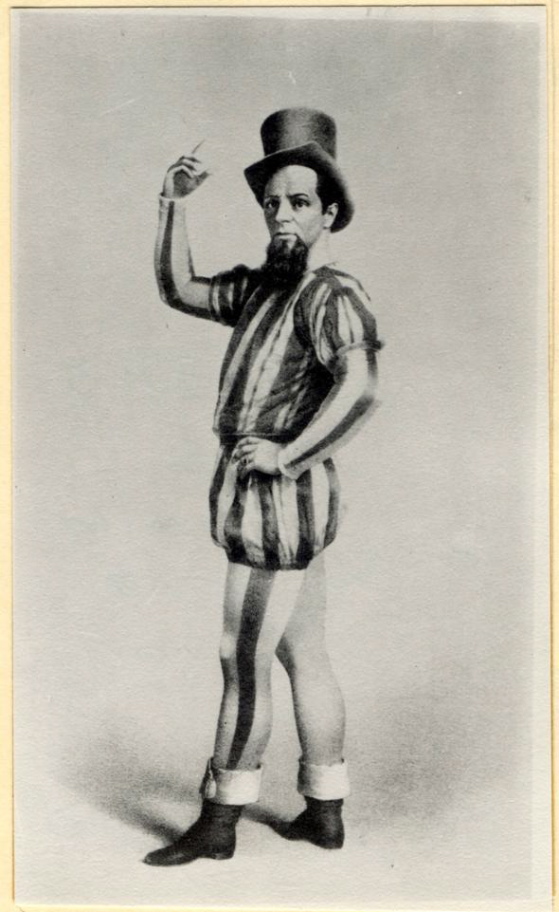

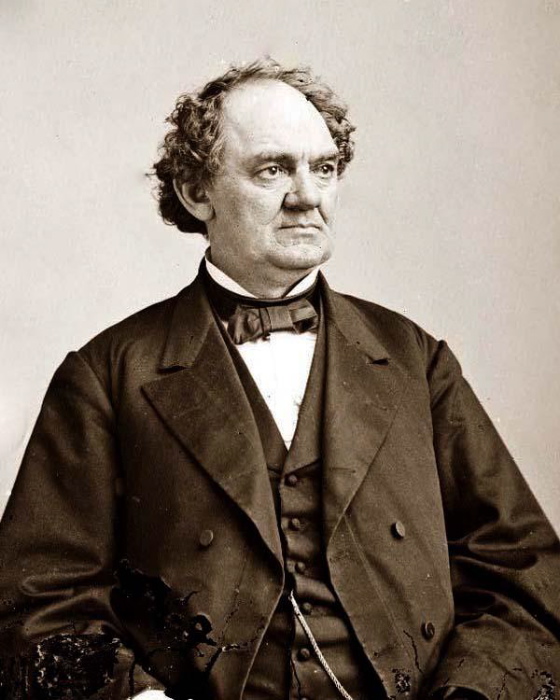

Dan Rice (above), described in the subtitle of David Carlyon’s biography as “the most famous man you’ve never heard of”, started out in the 1830s as the traveling exhibitor of a learned pig — it could count and tell the time. Then Rice got a horse and a tent and became a circus showman, the most famous of the 19th Century. P. T. Barnum (below) lent his name to an enterprise that became the most famous circus of all time, but wasn’t himself predominantly a circus man. He wasn’t even responsible for his circus’s immortal motto, “The Greatest Show On Earth’, invented by someone else as a topper to “Dan Rice’s Great Show”.

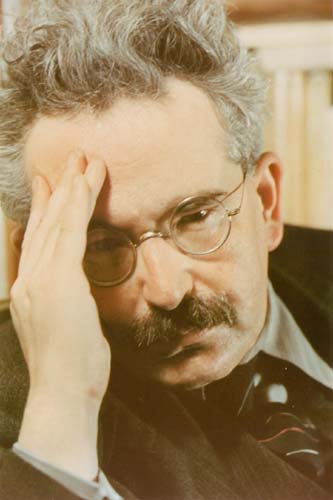

Rice was an accomplished horse and animal trainer but earned his immense renown as a clown, of a new kind. He sang and danced and did physical comedy, sometimes in blackface, and enacted parodies of Shakespeare, but captured the fancy of the nation with his comic monologues — often of a topical nature, ranging over the subjects of national and local politics (in whatever town his circus happened to be playing.) His specialty was audience interaction, improvisation in the moment — quick wit on the fly.

He so impressed the public that he was thought of as a great and wise man — a bit like Will Rogers in the 20th Century — and he was recruited to run for political office, including the Presidency, on more than one occasion.

Though he was the chief draw of his “Great Show”, it was still a circus. Its featured animal act was a horse named Exclesior, who could do astonishing tricks. Later on, when “menageries” (of exotic animals) became part of the circus, Rice enlisted an elephant who could walk a tightrope, a rhinoceros who could obey a few simple commands and a trained camel.

The menagerie of exotic animals developed apart from the circus, as an adjunct to the “museums” of curiosities which flourished in the 19th Century, and in which Barnum mostly specialized. The idea was imported into the circus as a new-fangled attraction.

In Rice’s day, the circus was a show for grown-ups, featuring plenty of sex, in the form of scantily-clad female performers, and sometimes crude humor. It morphed into a children’s fantasy only at the end of the 19th century — when its cruder offerings were moved over into the adjoining midway.

By the 1870s, Rice’s brand of verbal comedy had been absorbed into “variety” — a very crude form, for male audiences only, centered in urban areas, usually associated, physically and commercially, with saloons. This was the form that got cleaned up for mixed audiences (ladies as well as gents) of middle-class patrons in the 1880s and renamed vaudeville. It still had a lot of circus in it.

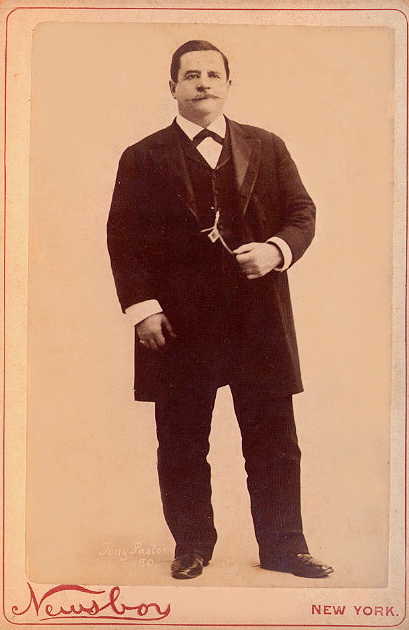

Tony Pastor, the impresario who led the way in cleaning up variety and did the most to popularize the new designation “vaudeville”, had gotten his start as a knock-about clown in one of Dan Rice’s circuses — and knock-about clowning always had a place on the vaudeville stage. So did the comic monologuist — carrying on a tradition pioneered by Rice.

Horses were gone, of course, along with the rings they raced around, but trained animal acts remained. One of the most popular and fondly remembered acts in vaudeville was “Fink’s Mules” — sometimes called the greatest opening act of all time — in which a blacked-up Fink engaged in a losing contest of wills with his expertly trained animals.

Dan Rice also had a mule act, with two mules that only he could ride. He’d dare audience members to try their luck with the animals, who inevitably bucked them off, to the delight of the crowd.

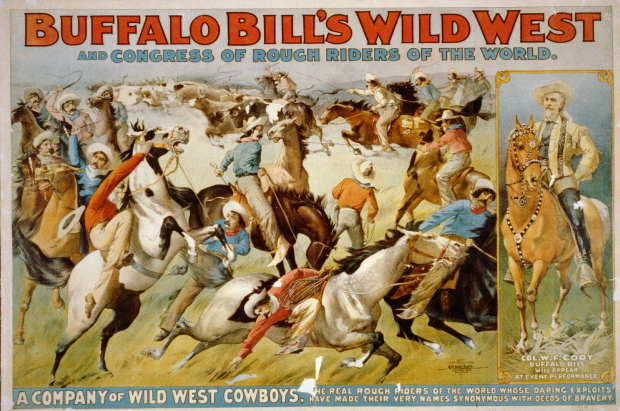

Horses and feats of horsemanship stayed in circuses, even though the exotic animals became the real stars, but horses took center stage in Buffalo Bill’s arena shows, a kind of circus masquerading as a historical pageant.

The chaotic popular entertainments of the 19th Century, always evolving, left their mark on the popular entertainments of the 20th Century — via vaudeville, which fed the Broadway and Hollywood musical with images, acts and talent, and supplied silent film comedy with its greatest clowns . . . and the rodeo, which carried on the circus’s and Buffalo Bill’s celebration of the horse. The classic American circus survives only in the two companies of The Ringling Brothers, Barnum & Bailey “Greatest Show On Earth”, but another kind of circus, classier and adult-oriented, thrives on the Las Vegas Strip. Now called “cirques” (as in “du Soleil”), they form the core of Sin City’s permanent live-performance attractions.

The continuum revealed in all this is not much remarked upon, a result of the 20th Century’s insistence on seeing itself as “modern”, freed from the shackles of the Victorian era, but also of the age-old tendency in show business to emphasize novelty. “A 19th-Century Attraction Reborn and Refurbished!” isn’t an ad line that’s going to pack them in on a Saturday night in the 21st Century — though it would offer a more reliable indication of pure entertainment value than almost any other.