. . . make a fateful decision — no more Mr. Nice Guy!

. . . make a fateful decision — no more Mr. Nice Guy!

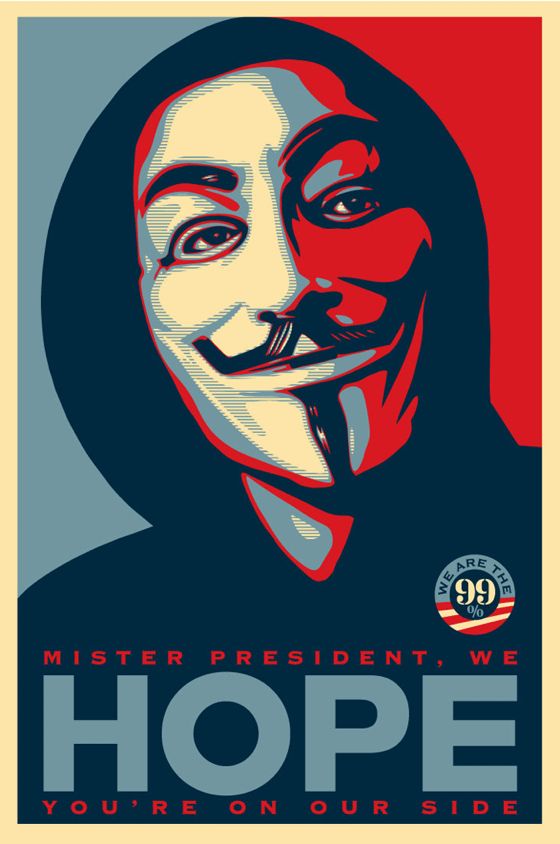

We heard a lot about hope from Barack Obama three years ago, but hope is where you find it, and you never find hope without courage.

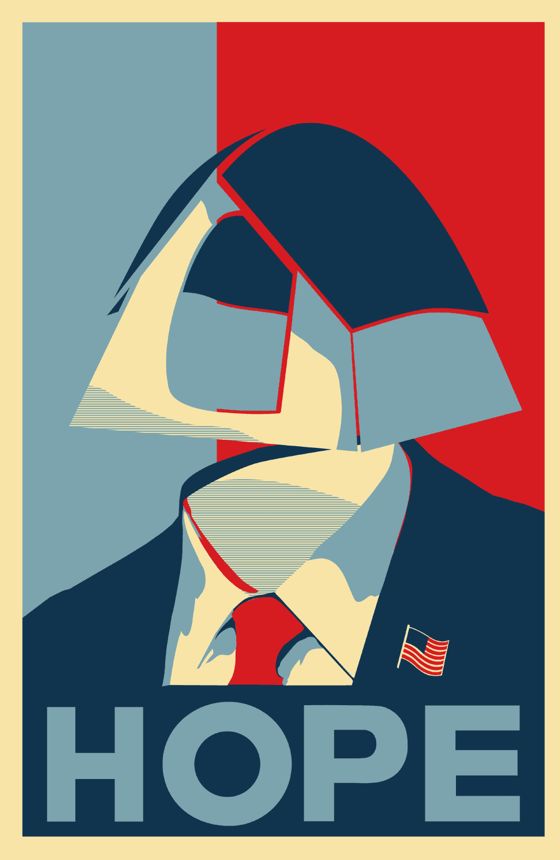

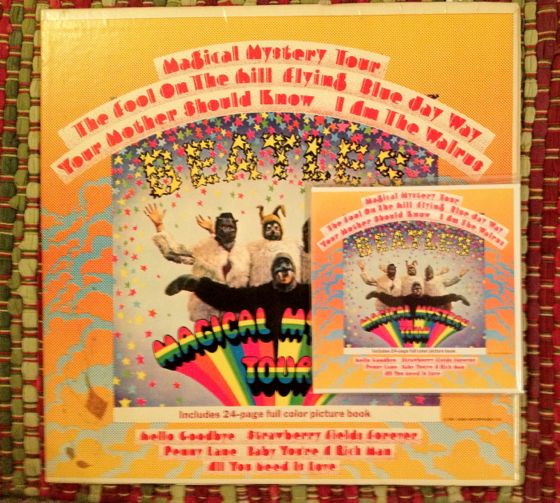

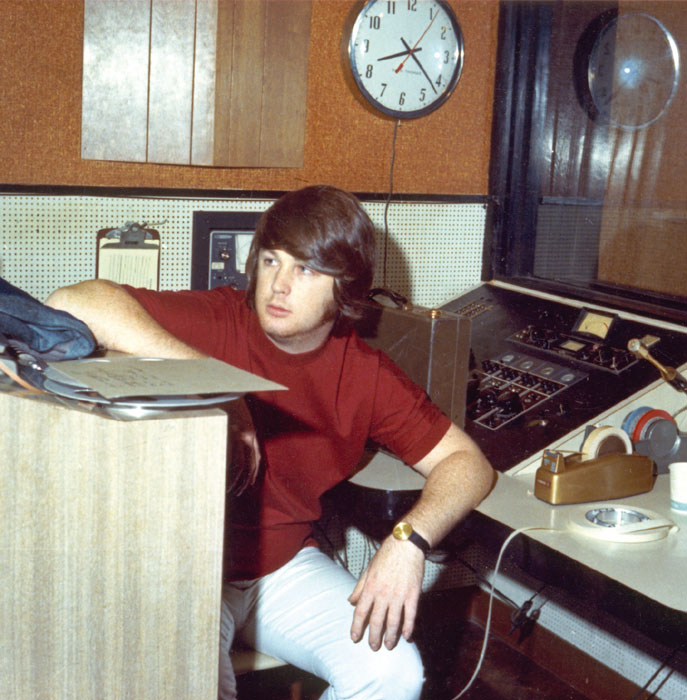

I recently got a new turntable — I'd been without a functioning one for

about 25 years, long enough, I reckon, to give me some perspective on

the experience of spinning vinyl.

I've heard people say that you can't really appreciate the superiority

of vinyl sound over CD sound except on audiophile equipment, but it's not

true. I have a decidedly non-audiophile music system and if I listen to a CD

after playing a couple of records I notice a difference immediately.

The CD sounds thinner, especially on the high end of the sonic range.

The ability to transmit the high end of a recording in warm, round tones

is what vinyl does best. And all across the sonic range it imparts a

presence to the music that a CD just can't.

CD mastering has improved dramatically in recent years. You can hear

the improvement best by comparing the first CD versions of the Beatles

albums with the new remasters. With the remastered CDs there's a marked

difference in the roundness and warmth of the tone. They almost sound

like vinyl — but not quite . . . and again it's in the high end of the

range that you notice the difference most clearly. When John and Paul

hit their high notes, their voices take on a slightly freeze-dried

quality.

The other aspect of spinning vinyl has to do, of course, with the ritual

of the thing. Pulling a record out of its sleeve, cleaning it, being

careful to set the needle down on it without harming either the needle

or the disc, getting up to flip the record over when one side is done —

these things put you in a certain specific state of mind. It conditions you to think of the disc as a precious object, and the music you're going to listen as special — an event.

I adore the convenience of having tons of music on my computer and

portable devices. It allows me to listen to more music, and more varied

music, than I otherwise would. (Twenty-four hours worth of Christmas music is still not quite enough for me.) But spinning vinyl encourages me to

listen to music more selectively and carefully than I otherwise would.

I'd never go back to black exclusively, but I also don't ever want to be without it again.

My niece Nora, currently studying at Hogwarts, gave me this handsome wizard's wand. I know I must use it for good and not evil, but sometimes it's hard to restrain myself. Lapses of moral judgment are possible. A word to the wise — if you're an attractive young woman and start to get inappropriate feelings for older men, please ignore them.

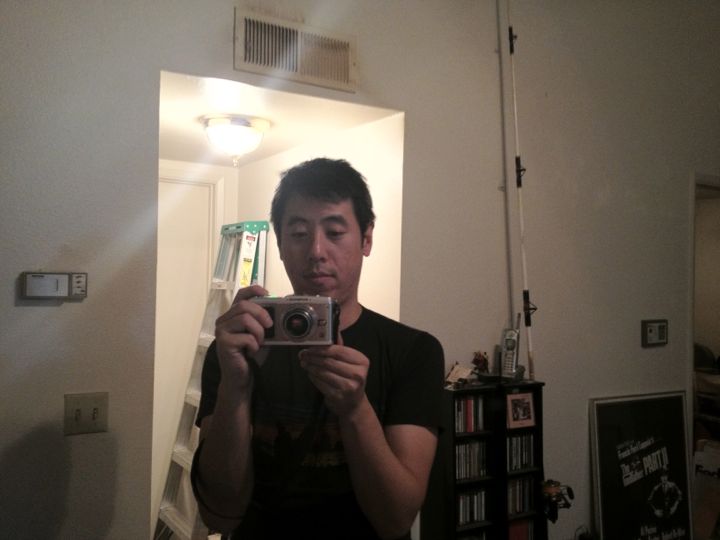

My friend Jae Song took the image above with a new camera system he's just put together — an Olympus E-P1 digital body, two years old, fitted, using an adapter, with a Kern Switar 25mm 1.4 C-mount lens, about fifty years old. The legendary lens, small, ruggedly-built and sensitive, was originally made for Bolex 8mm movie cameras and won't work with a digital camera which has too large of a chip, because it causes excessive vignetting. There are a number of digital cameras with chips small enough to accommodate a lens like this Kern Switar — Jae chose the 2009 Olympus because of its solid construction and retro body design.

The combination makes for a distinctive and to me quite wonderful look — quirky in the way that old lenses used to be quirky, each handling light and focus in a slightly different way. Jae thinks that this has to do with subtle flaws in the glass, which modern manufacturing methods tend to do away with. (The Olympus will also take impressive videos in 780p HD — go here for an example.) In any case, the look seems to harmonize well with the vintage technology of a turntable.

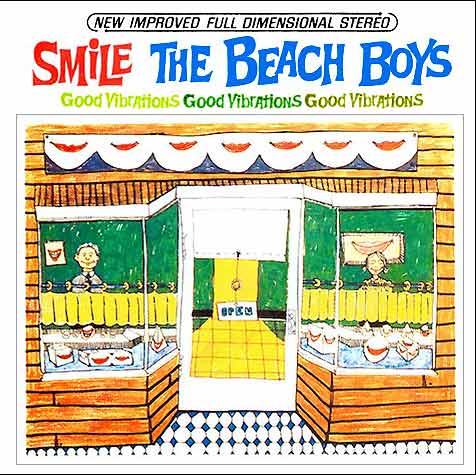

In re what's left of SMiLE, Brian Wilson's abandoned recording project for The Beach Boys from 1966-67, we stipulate to the following:

1) It is conceptually incoherent, at least from a rational point of view. It is probably not conceptually incoherent because it was abandoned before completion — it was probably abandoned before completion because it had no conceptual structure. Such a work could not by definition ever be completed. Wilson was working with some fuzzy ideas about what he wanted the album to be, but proceeded largely by feel.

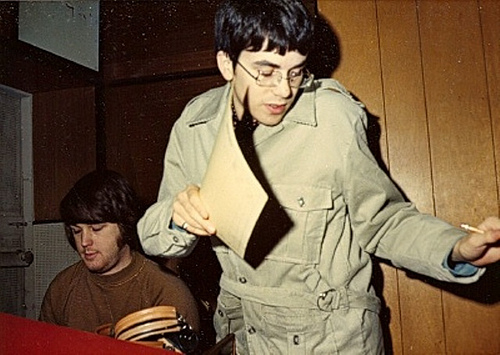

2) The lyrics, mostly by Van Dyke Parks (above), are uneven. Some are brilliant, some are overly precious, some are embarrassing.

But we find, after careful listening, that the following propositions are also true:

1) SMiLE is a great work of art, a masterpiece, and like nothing else in the history of American music . . . well, since Charles Ives, anyway. In Ives's work, Holiday Symphony, for example, Wilson could have found a workable intellectual rationale for what he was doing — a kind of collage strategy, with discrete passages of music connected to each other by the associations of memory (as well as the whims and tastes of the composer.) For all the musical influences coursing through SMiLE, though, I doubt if Wilson listened much to Ives, whose intellectuality and dissonance would not have appealed to him.

2) There is a coherence to SMiLE which derives from the sheer beauty and audacity of the music, and the logic of Wilson's own ear — the clear, utterly sensible flow of Wilson's joy in music, of every kind, from hymns to doo-wop. It's all unified further by the magical harmonies Wilson conceived for the voices of The Beach Boys. He recorded the vocal parts over and over again, trying to get the transcendent effect he was after — that little bit of magic beyond the sweet sounds that would constitute a proper musical offering . . . to God, as he saw it. He wanted SMiLE to be a musical offering to God.

3) SMiLE is a musical offering to God, of the best Wilson felt was inside himself. He wanted it to be more than he could realize at the time, but it's enough, as it is — a worthy offering.

4) Because the music is modular, built of passages connected to each other mostly by feel and intuition, it's possible to listen to the studio outtakes with the same pleasure and sense of discovery one has when listening to the reconstruction of the proposed whole. The musical passages are brilliant tesserae that can be combined into any number of mosaic patterns — each of which offers a different and wondrous new image.

Jae eats Thanksgiving dinner, crashes, wakes up early on Black Friday and heads for the Luxor, where he joins a morning poker tournament, starts drinking and going all-in when he has anything resembling a hand. Finishes first in the tournament. Just another ordinary day in Las Vegas.

Jae Song rides his first Harley, looks cool.

A couple of days ago my friend Jae and I entered a three-table late-night poker tournament at Bill's Casino on The Strip. It had a thirty-dollar buy-in and the top three finishers, out of about thirty players, got paid. I “cashed”, finishing third, and won fifty-eight dollars, or would have if I hadn't made a bonehead play on my third or fourth hand — an ill-advised all-in that felted me and forced me to re-buy. So I ended up twenty-eight dollars ahead but with the satisfaction of feeling, for a few hours afterwards, like a poker god.

[© 2011 Huger Foote]

Despite its subject matter, dead leaves in a gutter, this image has a delicate, sweet quality, and something of the feel of a Japanese woodblock print.

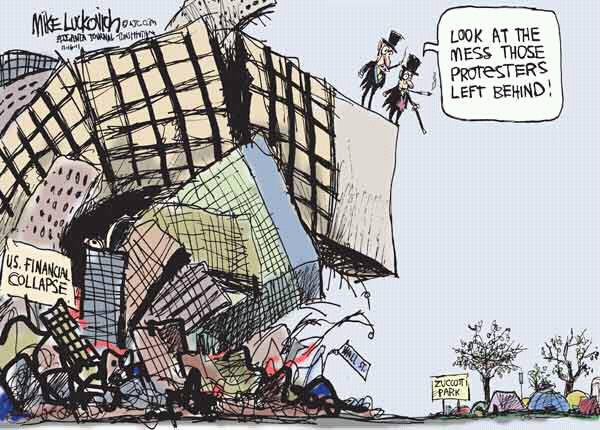

. . . that there are still people who think Obama is “doing the best he can” and might secretly stand with the 99%. What good is secret sympathy? Has he uttered even a peep in support of the OWS goals or against the excessive force being used against the protesters? Is he going to have to pick up a police baton and smash an old woman in the head with it before people get the message?

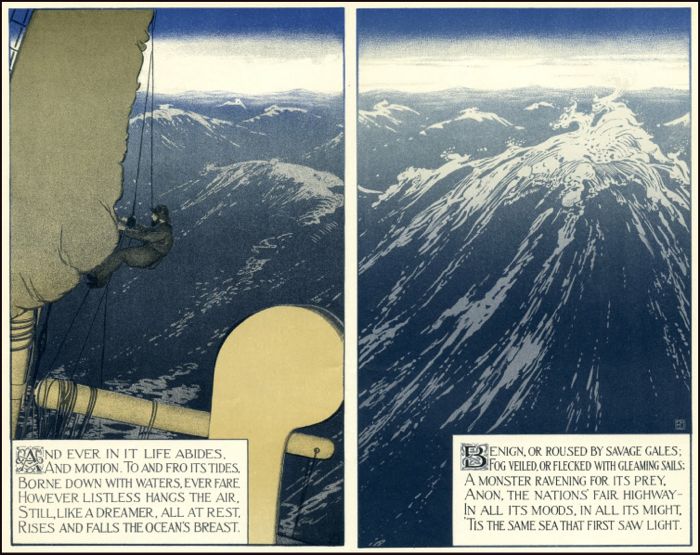

Illustration by Henry McCarter for the Century Magazine, 1898.

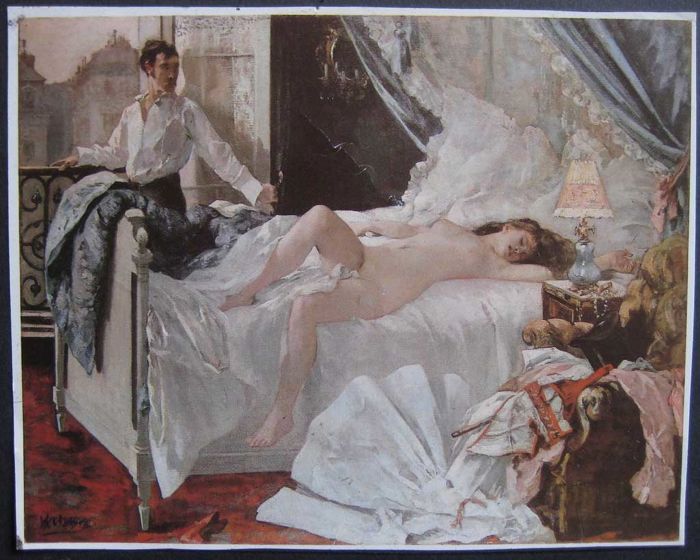

This painting was refused admission to the Salon of 1878 on the grounds of indecency — quite rightly, I think. Degas had convinced his friend Gervex to show the lady's discarded corset on the chair beside her, which didn't help.

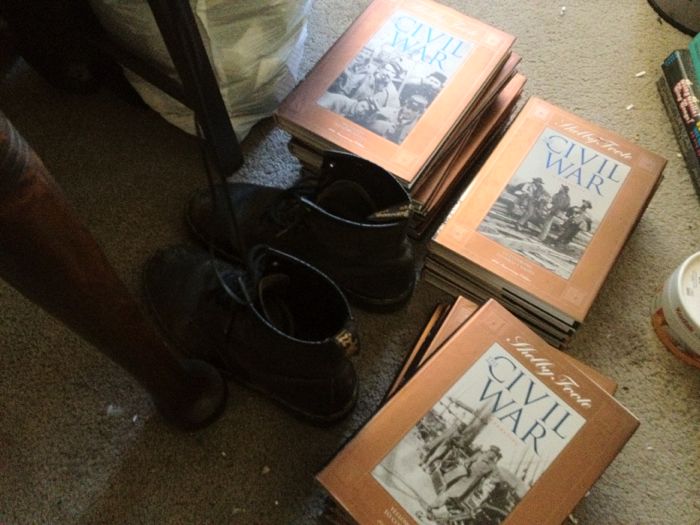

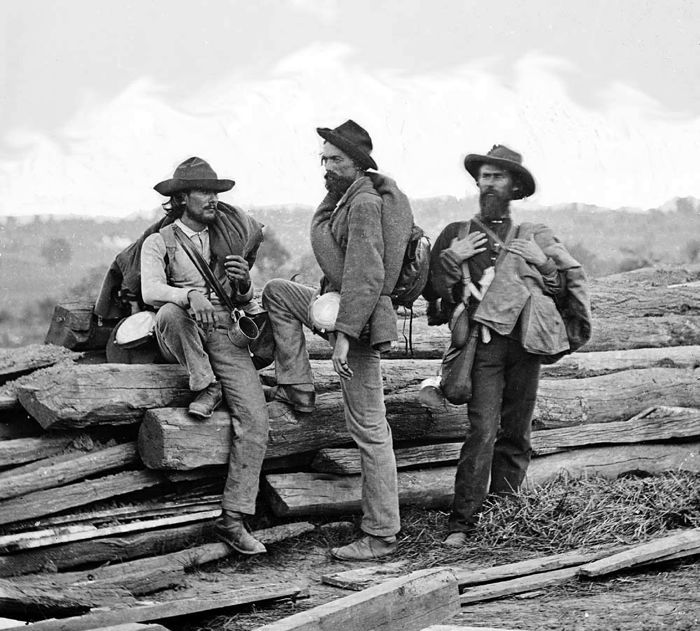

This is Shelby Foote's massive three-volume, three-thousand-page narrative history of the Civil War, in a fourteen-volume illustrated edition published by Time-Life to commemorate the 40th-anniversary of the appearance of the first volume.

I read it when the third volume appeared, in 1974, and it instantly became one of my favorite books. If there has been a greater work of literature written in America in my lifetime, I don't know what it would be. I've always meant to read it again, and thought this illustrated edition would be a good one for a second visit. It will be my winter reading project.

I wouldn't recommend this version for a first read — Foote's prose is so fine that it really ought to be experienced initially on its own — but this edition has the virtue of being less daunting, taken one slim volume at a time, and the pictures and color maps are cool.