American

popular literature has a long grotesque tradition, stretching back to

Washington Irving, our first literary celebrity. It achieved its

apotheosis, in terms of both sensationalism and art, in the work of

Edgar Allen Poe — and it migrated naturally into the exaggerated

conventions of Victorian theater, and from there into movies.

After

WWI, and perhaps in part owing to the unprecedented horrors of that

conflict, grotesque melodrama became a distinct genre in cinema, much

as film noir became a distinct genre after the collective nightmare of

WWII. Its power and prestige is best illustrated by the extraordinary

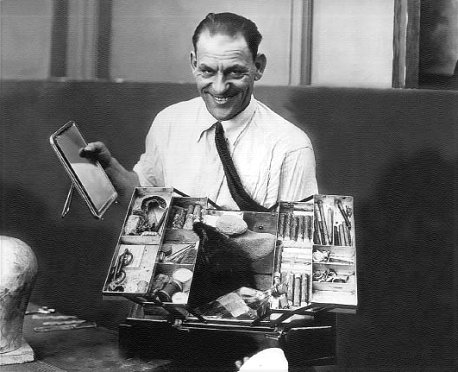

popularity of Lon Chaney. One of the most celebrated stars of the

silent era, he specialized almost exclusively in the genre of the

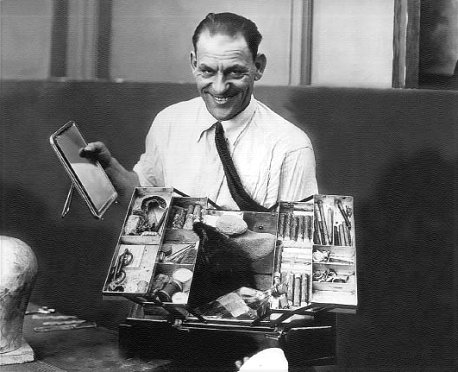

grotesque. (He's seen above in and out of make-up for The Miracle Man.)

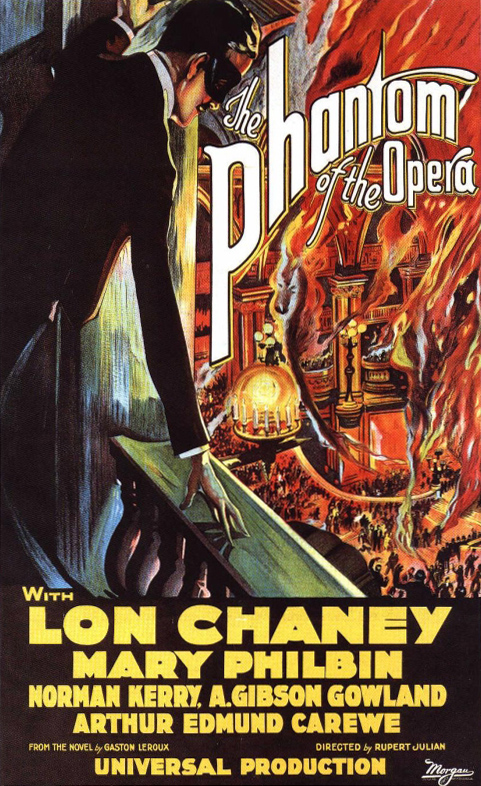

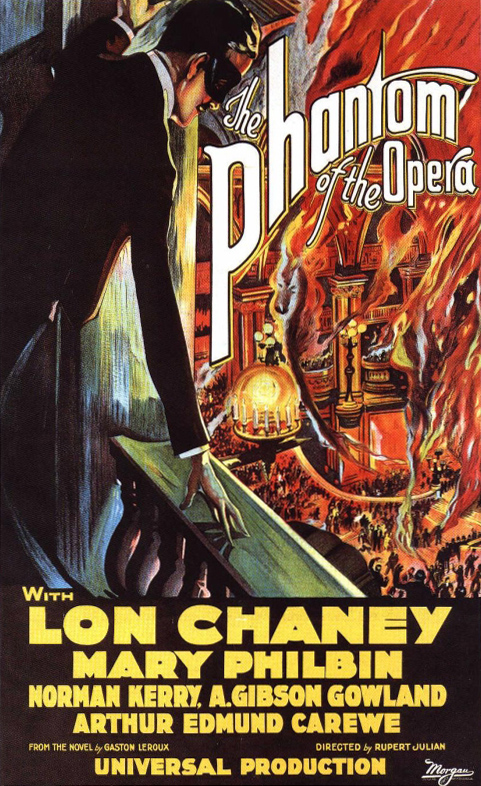

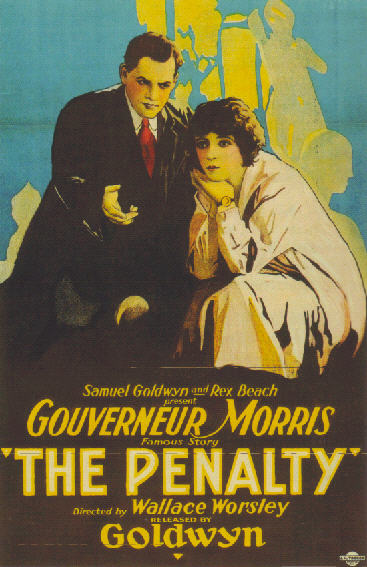

In

tracing the rise of the modern horror film from its roots in silent

cinema, we can easily misconstrue the grotesque genre as it was

experienced by early audiences. The Phantom Of the Opera and The

Hunchback of Notre Dame, proto-horror films starring Chaney, actually

have more in common with a grotesque contemporary melodrama like The

Penalty, also starring Chaney as a legless underworld crime boss —

and the three have more in common with each other than any of them has

with Dracula, for example, with its supernatural elements, or even Frankenstein, with its elements of mad-science fiction.

The

Phantom, the Hunchback, and the legless Blizzard from The Penalty are

all disfigured men whose afflictions have rendered them terrifying,

while not quite extinguishing the romantic souls within. It's hard not

to see in this an echo of the many thousands of mutilated survivors of

WWI, and a metaphor for the psyche of a world scarred by previously

unimaginable battlefield carnage.

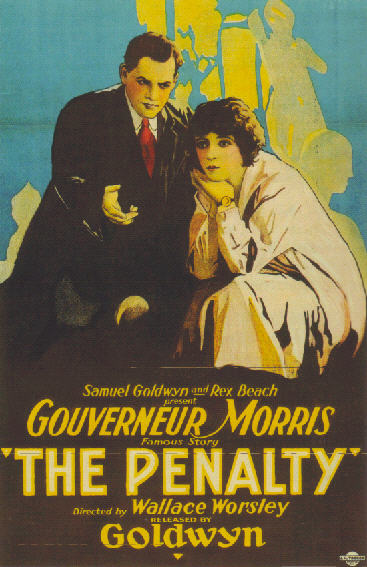

The

word grotesque does not quite describe the dramatic tone of The

Penalty or the world it creates. Demented is closer to the mark. It

does not present us with a vision of normality penetrated by grotesque

elements — it is set in a universe which has become unhinged at the

core, and this nightmare universe is delineated matter-of-factly, as

though its logic were the logic of the world as it is.

This

creates a wonderful, dreamy kind of surrealism, with great poetic

force, and a delightful atmosphere of frisson — but it is finally very

disturbing. One is tempted for this very reason to dismiss it as lurid

pulp, but one cannot — mostly because of the authority of Chaney . . .

the physical authority of his shockingly convincing impersonation of a

legless man, and the artistic authority of his performance as the

paradoxical Blizzard.

We are

given to drawing a distinction between silent film performers who

“over-acted” and those who played in a more restrained and “modern”

style. Chaney is usually considered more modern in this sense. But in

truth, Chaney overacts in every frame of The Penalty, by modern

standards. It's just that the broad strokes of his expressions and

gestures are so grounded in psychological truth, so complex in their

suggestiveness, so graceful and sublime in their execution, that we are

swept beyond our modern expectations of what acting should be. We are

experiencing screen performance as audiences of the time experienced

it.

The

intimacy of the camera certainly did require a technical toning down of

physical expression and gesture for actors coming from the stage —

much as a smaller theatrical venue would have for actors accustomed to

playing huge auditoriums — and there were certainly lunkheaded actors

who couldn't pull this off. But most of the time, when we talk about

the difference between over-acting and more naturalistic acting in

silent films, we are simply noting the difference between bad acting

and good acting.

One of

Cocteau's great maxims was “You have to know when it's all right to go

too far.” Great silent film actors knew this — and great modern actors

know it, too. James Cagney and Jack Palance — and Jack Nicholson, for that

matter — habitually overact by so-called modern standards, yet their

performances still seem fresh and convincing, perfectly au courant.

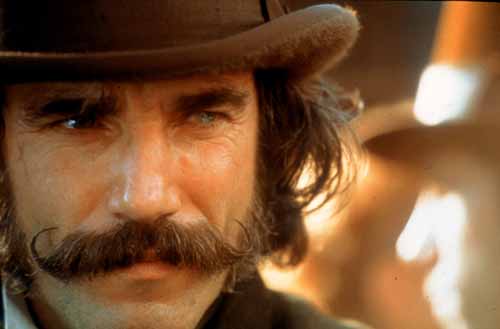

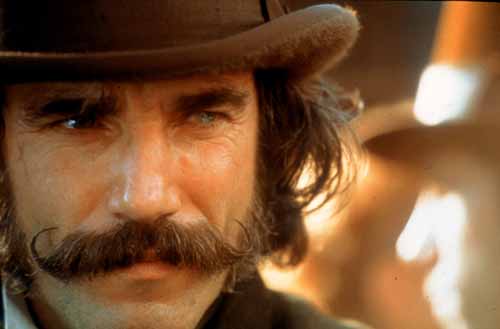

Daniel Day Lewis's performance in The Gangs Of New York, one of the

very greatest performances ever committed to film, is as wild and

over-the-top as any silent film performance ever was, and yet it is a

work of complicated and compelling genius.

The

camera did allow a new breed of actors to step to the fore — the

minimalists, of whom Robert de Niro is probably the most astonishing.

But Lon Chaney was no minimalist. He was an actor in the grand style —

and, quite simply, a supreme master of that style, consistently

pitch-perfect, and consistently breathtaking.

The

delirious tale of The Penalty begins with a boy injured in a traffic

accident, treated by an incompetent doctor who unnecessarily amputates

both his legs. An older doctor covers for the younger physician's

mistake, and the chastened bumbler goes on to an exemplary career in

medicine. But the boy never forgets.

He grows up to be the crippled criminal mastermind Blizzard, played by Chaney, who amasses power, covets more, and plans

his revenge — on the doctor and on the world.

On

the first front, he insinuates himself into the life of the doctor's

daughter — a sculptor torn between her ambitions as an artist and

society's expectations of exemplary womanhood (domestic and submissive)

— by posing for her portrait of Satan. On the second front he is

plotting a takeover of the city of San Francisco by means of a lunatic

scheme involving ten thousand “foreign malcontents”, armed to the

teeth, and uniformed in silly matching straw hats, cunningly woven in

advance by harlots conscripted from the ranks of Blizzard's working

girls.

It's all quite mad, but presented as an authentic threat to the civil order.

A

subplot involves a plucky undercover female police operative who

infiltrates the crucial straw hat operation and quickly learns more

than it's safe for her to know. Principally she discovers the

underground lair where Blizzard stores the munitions for his planned

insurrection — a subterranean world, reached through a trick

fireplace, that's right out of the wildest Gothic fiction, and vaguely

reminiscent of Erik the Phantom's underground kingdom beneath the

Opera.

Blizzard is a beast, with the soul of a poet. He is a fine critic of art, and fires the sculptor with the courage she

needs to break free of her bourgeois shackles and strike out on her own for glory. Villain indeed!

Blizzard

also wins the heart of the undercover operative by his soulful piano

paying — and she wins his by her skillful operation of the pedals

while he plays. She comes to her senses only when she discovers that

his grand plan involves amputating the legs of a certain . . . but you

get the idea.

Female independence is presented as possibly sexy and possibly admirable but, in the end, a very bad idea, for which a

woman will inevitably pay a dreadful price.

The

preposterous villainy resembles the harebrained villainy of Feuillade's

serials — at once innocent and unsettling, mundane and surreal.

Possibly both reflect a post-war malaise informed by a sense that the

ordinary world has gone subtly but irrevocably insane.

Chaney's

performance, as usual, gives it all an unlikely interior coherence and

logic. The filmmaking is aptly described by Michael Blake, Chaney's

biographer, as craftsmanlike — the shots are handsomely framed and

lit, and the narrative moves along at a lively clip. Chaney alone

elevates the film to greatness.

Every

time he moves himself around with his crutches or with his hands alone,

we watch a ballet on stumps unfold — the aesthetic determination and

commitment of the actor become the villainous determination and

commitment of the character he's playing. We admire him and recoil from

him at the same time.

This

is the thrill of the grotesque drama. We are allowed to engage and

embrace our deepest fears and discontents subconsciously, while

retaining our outward allegiance to conventional virtues. The film

dangles the possibility of Blizzard's redemption before us — then

snatches it away at the last moment . . . as it snatches away the

possibility of new horizons for the women.

The

ultimate effect, however, is one of ambiguity, a suspension of faith in

the old certainties — an intriguing discombobulation of the moral

universe.

Kino's

edition of the film on DVD features a splendid print and some wonderful

extras. They include the surviving footage from The Miracle Man —

which is painful to watch, because this lost film looks as though it

might have been marvelous. Included also is one of the few surviving

one-reelers from Chaney's early years at Universal — By the Sun's

Rays. It's not much of a film, but it's fascinating to see Chaney at

work at the beginning of his movie career. His physical grace commands

attention, even when his choices as an actor are obvious or even crude.

Chaney was born for the screen, as Chaplin and Pickford were — with an

instinctive insight into the movies's mysterious expressive power.

There

is, perhaps most delightfully of all, a brief short in which Michael

Blake shows us some of the Chaney artifacts held by the Los Angeles

Museum of Natural History. We see the suit and the stumps Chaney wore

in the movie, his make-up case — the mirror he looked into while

working his magic. Blake handles them all with the delicate hands of a

make-up artist, which he is — and the awed respect of someone who

genuinely admires the craft of a master.