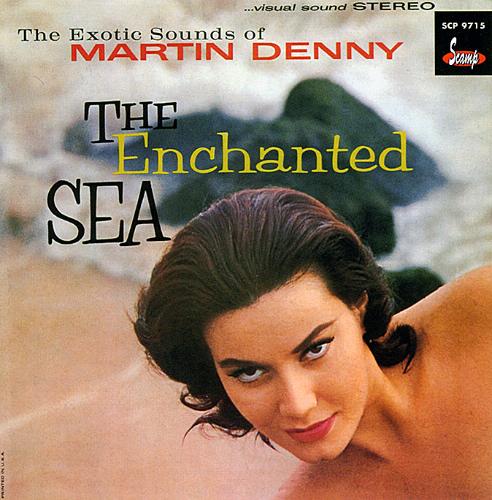

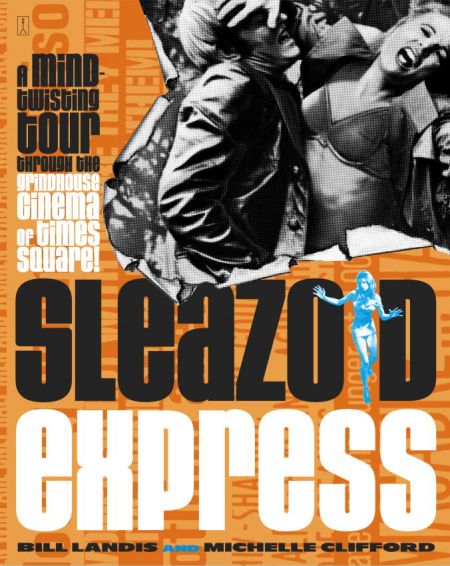

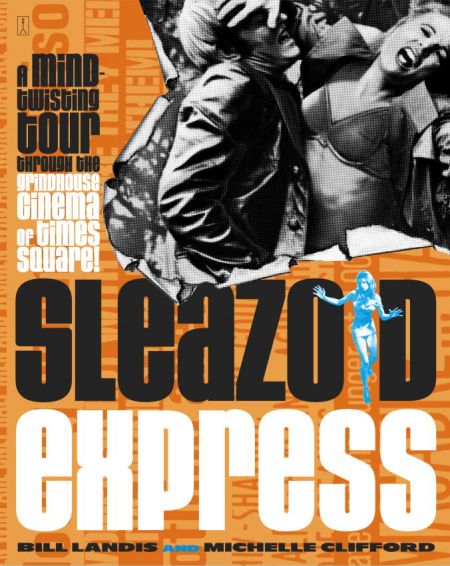

Over on Illusion Travels By Streetcar, Tom Sutpen has posted a poetic tribute to the book Sleazoid Express, which summons back the long-gone days of pre-Disney 42nd Street in Manhattan, when former legit theaters which had become grind movie houses showed exploitation films to the hustlers and grifters who called that part of town home.

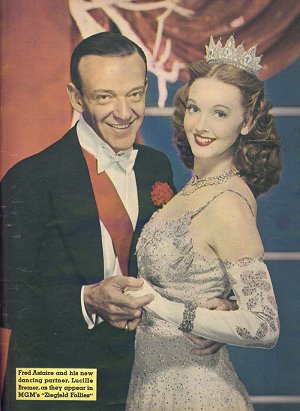

As it happens, I was just watching an interview with Michael Eisner about Disney's decision to refurbish the New Amsterdam Theater on 42nd street, which had fallen below even grind-house standards. Its grand interior, which once housed the Ziegfeld Follies, was open to the elements and home only to birds. Eisner describes telling Rudolph Giuliani, then the mayor of New York, of his fears that family audiences might not feel comfortable visiting that part of town, with its grind houses, sex shops and massage parlors. “They will be gone,” said Giuliani.

“They can't just 'be gone',” Eisner said. “I mean, you've got the ACLU, free speech.” “Look in my eyes,” Giuliani said, and repeated, “they will be gone.”

By the time The Lion King opened in the beautifully restored New Amsterdam, they were gone. Sleazoid Express is about what was swept away to make room for Simba and company.

Sutpen suggests why we should remember this lost world, which is why we should remember all the “unexamined” aspects of our culture — because they often provide greater insight into who we really are than cultural manifestations which have the full support of city police departments.

Back in 1908, when 42nd Street was an upscale theatrical Mecca, nickelodeons, the grind houses of their day, were showing the first films of D. W. Griffith. In sleazy dives on the shabbier side streets you could hear “Negro music”, the precursor to jazz. In other words, there was a time when the two great art forms of the 20th Century were part of America's marginal culture, its unexamined culture.

Whatever the exploitation films of the Sixties and Seventies represented, it was important, and it isn't gone. By the same token, as Sutpen notes, the Times Square Renaissance, which turned a scary part of town into a family-safe part of town, also began a process by which Manhattan has been transformed into a mall-like environment for tourists, losing its urban juice and spirit. What began as a rebirth in Times Square inaugurated a kind of lingering death for one of the world's great cities.

Culture, too, has its own circle of life.