This is the seventh in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin . . .

In an article on film and painting, André Bazin argues that the frame around a painting has the purpose of cutting it off from the real world, establishing the limits of a conceptual field necessary to analyzing the painting in its own terms . . . while the frame around a cinematic image is not a boundary marker but merely a masking device, blocking out an infinite expanse of space which we are meant to imagine as existing outside the mask.

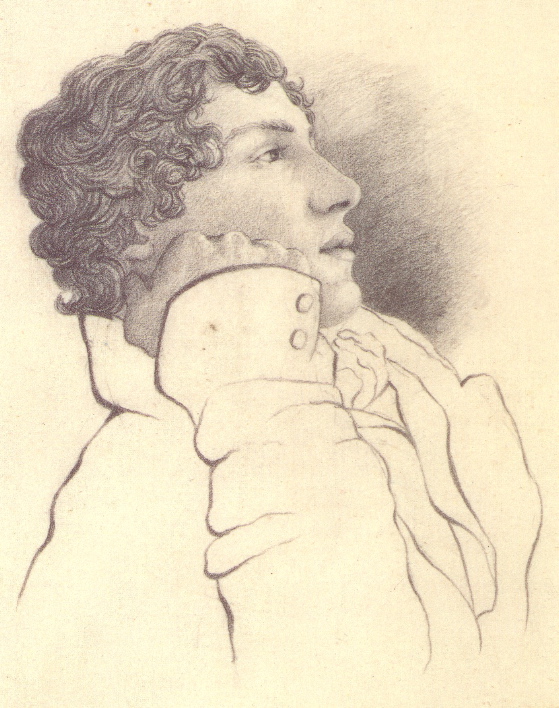

This doesn't seem quite right to me. There are certain kinds of painting which evoke the world with an optical integrity, an über-photographic reality, which make it not only possible but desirable to imagine a universe beyond their frames. Much Victorian academic painting has this nature — it was a quality of painting which modernism rejected but which still had its virtues. Some “classical” painters used this quality — Vermeer, for example. The conceptual universe of Vermeer's paintings does not end at the edges of his frames.

And the frame of a cinematic image is often much more than a mask — a device for focusing attention. It sets the boundaries for creating a drama of space, exactly as the proscenium arch does in classical ballet. The distance or nearness of two dancers in a ballet only has dramatic meaning in relation to the space defined by the proscenium arch. In ballet, the frame of this arch doesn't just demarcate an arena of theatrical illusion — distancing it from the real world inhabited by the spectator — it has a functional role in defining the expressive terms of the dance.

It's true that in photographed cinema, as opposed to animation, say, we can readily imagine a world beyond the frame with the same ontology as the actual objects photographed within the frame, but there is a counter impulse to discount this peripheral world in order to read the space within the frame as a theatrical arena whose dramatic content only makes sense within that frame.

Take the scene in The Searchers, for example, when Debbie appears in the far distance on top of a ridge behind Nathan and slowly moves towards and into the foreground space they occupy. This becomes a visceral objective correlative to Nathan's dawning acceptance of Debbie as an individual human being, not just a symbol of his sense of disenfranchisement as a man, an object for the vengeance he wants to visit on life.

The shot is an image of a real place in a real moment of time, but we cannot imagine the world beyond its frame, we cannot imagine the space as seen from Debbie's perspective, for example, and still experience the full meaning of the shot. The frame here acts as a frame does with most paintings — it creates a conceptual field distinct from the world beyond its borders, and only within that conceptual field does the shot “work”.

Bazin's formula is just too simple. In the paintings Alma-Tadema did of the ancient world, we feel that the frame is indeed just a mask — a window onto a whole lost world beyond its frame which we delight in imagining. And conversely, when we are swept into the space of a great animated cartoon, it's hardly necessary to seriously imagine a whole cartoon universe beyond its frame.

We can imagine such a universe beyond the cartoon frame, just as we can, with much less effort, imagine a world beyond the ridge Debbie appears on, but it's the way the frame limits such images, takes them out of the larger world, that makes their meaning in purely cinematic terms possible.

Here again, I think it's Bazin's location of cinema's power in photographed reality, rather than in the drama of space, that leads him to a deficient theoretical proposition.