THE FILM

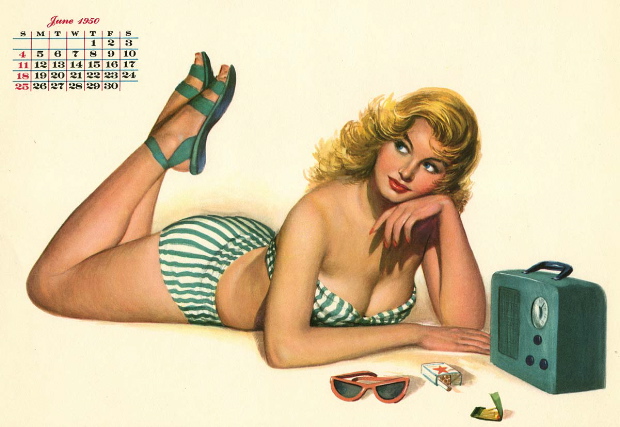

The genius of Hollywood in its Golden Age was in glamorizing simple virtue — the most famous case in point being Casablanca, which managed to make the sacrifice of true love for a higher cause seem unspeakably cool.

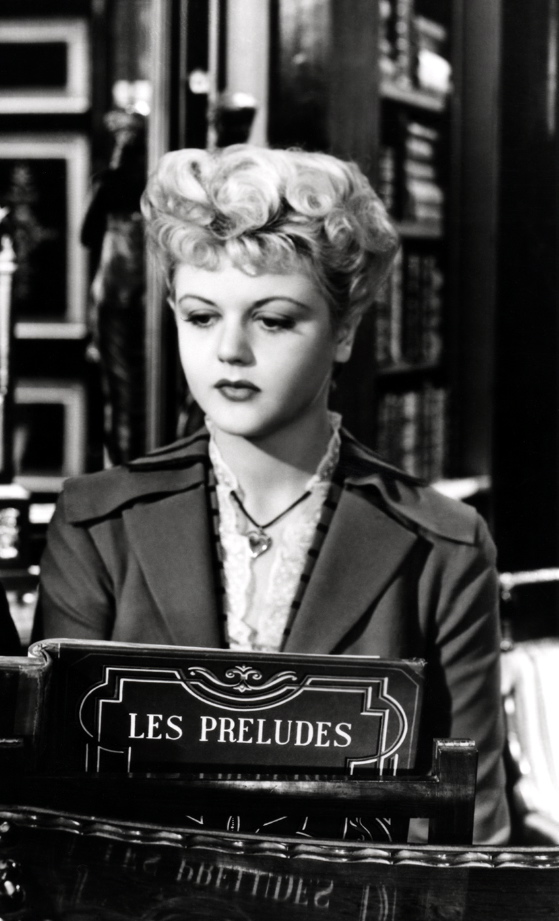

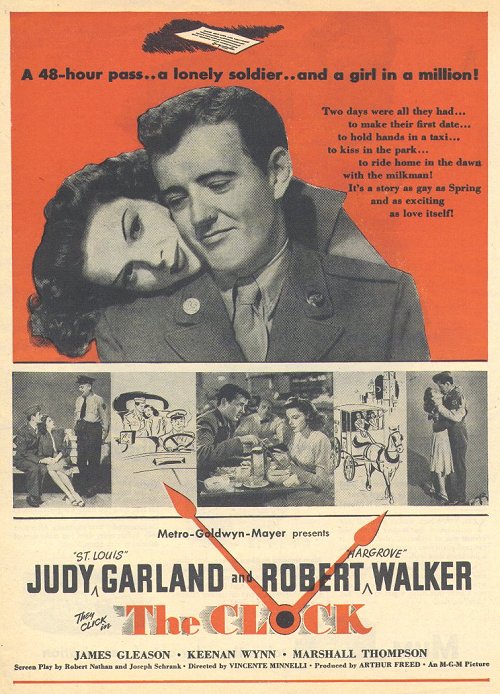

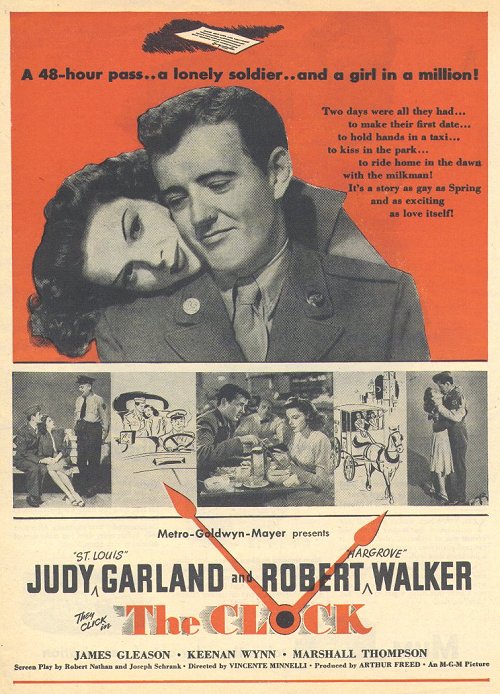

Another film made during and about WWII is in some ways even more impressive and certainly more moving. In Vincente Minnelli's The Clock Judy Garland plays a Manhattan secretary who meets a serviceman, played by Robert Walker, on 48-hour leave in the city before heading overseas.

What “heading overseas” suggested when the film was made (1944) has to be kept in mind while watching The Clock today, because it's crucial to every moment of the film, which takes the full measure of what it means to fall in love in the face of mortal peril. In some ways the gravity of the lovers' predicament in this tale is what allows Minnelli to pull off the miracle at the heart of it — giving the story of two totally ordinary people the grandeur of the most sublime romance from legend or myth.

James Agee wrote a beautiful appreciation of the film when it came out, which can be found in his collected criticism, Agee On Film, and can't be improved upon, but check out this interesting view from a contemporary blog, The Sheila Variations. It's worth pointing out, too, that this was the first non-musical film directed by Minnelli and produced by Arthur Freed, who had the previous year collaborated on one of the greatest movies ever made in Hollywood, Meet Me In St. Louis, a musical also starring Judy Garland.

Garland and Minnelli were in love during the making of these films, and Minnelli's feeling for the actress informs every frame of them — she is a radiant being in these movies, glamorized, certainly, but in a down-to-earth way that suggests the way ordinary people glamorize a new love. Minnelli seemed to find everything about her enchanting, which is why he could present her in such simple roles without feeling a need to “sell” her charms in any way, to make her larger than life. For him, clearly, she was already larger than life, even when she walked across a room or ate some soup.

Garland doesn't behave like a star in The Clock — she doesn't need to. The state of being loved relieves her of the need to appeal to any outside authority for approval. The result is paradoxical. She grows as an actor, becomes more fascinating as a screen presence, even as she retires into herself, makes us comes to her.

Like James Cameron's Titanic, The Clock manages to convey the narrative of a life-long love in a very compressed period of time — the awareness of death in both stories allows us, as it forces the characters, to read immense import into the simplest gestures, the most modest acts of sympathy and kindness, the plainest impulses of physical attraction.

In The Clock, as in the beginning of any real love affair, less is more. The way Garland adjusts Walker's tie at the train station before saying goodbye to him tells us more about the wedding night they've just shared than any dramatization of it could have suggested. Its very discreetness evokes the privacy of genuine intimacy, and yet we share it, not as voyeurs but as privileged participants in its magic.

As Garland leaves Walker's train the camera follows her and then rises up inexorably, in one long, tracking crane shot, until she's lost in the crowd at the station — her story, which is our story, too, now, becomes one story among many, and no less extraordinary for that.

THE VISUAL STYLE

Although the tracking crane shot described above is one of the most beautiful and effective single images in all of cinema, The Clock is not a consistently interesting film visually. Set in New York but shot almost entirely on the back lot of MGM in Culver City, it relies very heavily on backscreen projections, which cumulatively produce a claustrophobic effect. This doesn't hurt the story too badly, since part of Minnelli's strategy in telling it is to focus our attention closely on the growing intimacy between Garland and Walker, which he charts with great delicacy. The body language of two strangers falling in love has rarely been evoked with such precision and sympathy. It's a “visual effect” which, more often than not, trumps cinematic style.

The sound-stage recreation of the train station is spectacular, consistent with its crucial role in the drama, as is the recreation of the subway stations where the lead characters lose each other, in a brilliantly shot and choreographed passage.

Citizen Kane, made just a few years earlier, contains this same mixture of spatially seductive choreography on sets and relatively alienating process photography. In Kane, the mixture is weighted towards the former, in The Clock towards the latter, though Minnelli demonstrates his mastery by reserving the “set” pieces for passages where he really needs them — where a visceral appreciation of the space the characters inhabit is crucial to the emotional effect of the scenes.

But there are moments when the process photography undercuts the emotional effect — as in the scene where Walker runs after Garland on the bus. It's a cute gag played against process screens — it would have been heart-stopping played on a practical set or a real location.

THE CONTEXT

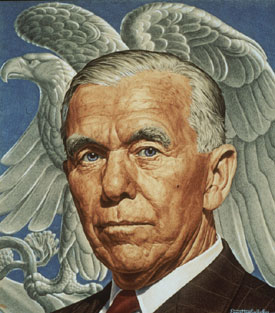

“Glamorizing virtue” was part of the commercial calculation of Hollywood, especially at MGM, where studio boss Louis B. Mayer insisted that MGM films promote “family values”. These were values that Mayer touted but did not practice. In middle age he dumped his aging spouse for a more glamorous trophy wife. He treated his stars like farm animals — pampered farm animals, admittedly, ones he expected to win him blue ribbons at the county fair.

Mayer copped feels from the teen-aged Garland at every opportunity, even though he wasn't especially attracted to her — he was just exercising the greengrocer's prerogative to squeeze the produce. MGM plied Garland with amphetamines when her work load slowed her down, then “graciously” paid for her rehab when she crashed, hoping they could still get some more mileage out of her.

This sort of hypocrisy is visible in many of the sentimental films made at MGM — like the wildly popular Andy Hardy series, made for peanuts and consistently profitable for almost a decade. Mayer loved these films, but seen today they reek of calculation and exploitation. All their sentiment seems not only contrived but downright cynical. The films do have their moments — the homespun virtues they celebrate are intrinsically attractive — and if you're in the right mood they can get to you. More often you're keenly aware of being manipulated by shrewd hacks.

Arthur Freed, who produced The Clock, and most of MGM's great musicals, was hardly a saint, and is reported to have had recourse to the casting couch at MGM on occasion, but he was devoted to his family throughout his life, and he imbued everything he worked on with genuine feeling — contrived, certainly, engineered with old-fashioned theatrical calculation, but never cynical, even for a moment. His films could be corny, way too obvious and even clumsy in their appeal to the heart, but you never get a sense that the artists who made them are trying to put something over on you they don't believe in themselves.

Freed's sincerity is what elevated films like The Clock and Meet Me In St. Louis above the sort of saccharine platitudes found in the Andy Hardy series. One can say for Mayer that he recognized the real thing when he saw it and backed Freed to the hilt as a producer, even when the other great minds on the lot dismissed Freed's stories as simple-minded. Freed rewarded Mayer's faith with sublime works of art which also made money — with films which now constitute the core of Mayer's legacy. Without Freed, that legacy would consist mostly of clever junk like Love Finds Andy Hardy, which plays today like a mediocre, padded-out sitcom.