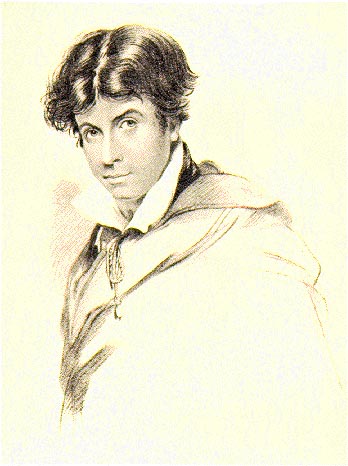

The fourth in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin . . .

André

Bazin was exhilarated by the idea of a cinema grounded in photographic

images that conjured up an intense illusion of space. He saw this

as the center of cinema's power. Montage, he believed, created

only secondary and less powerful effects, merely intellectual and

therefore not as profound. Cutting between shots of a single

location could create a mental impression of the space of the location

but not a visceral sense of experiencing that space first-hand.

“Metaphorical montage”, cutting between images to create a conceptual

relationship between them — as between a shot of a kiss and a shot of

fireworks going off — he saw as equally “intellectual” and thus

equally secondary. Cutting, he believed, tended to undermine the

power of cinema to imaginatively, as opposed to rationally, engage us.

He was on to a signal truth here, but there are some problems with his

argument. He consistently identified cinema's spatial illusion

with realism, and saw that realism, the shared ontological identity of

an actual space and its photographic record, as crucial to cinema's

power. However, as I've argued before, this fails to account for

the cinematic power of hand-drawn or computer-generated images, both of

which can create impressions of spaces which can engage us

imaginatively just as powerfully as photographic images.

Consider also the realm of dreams. We often in dreams enter

spaces which have no correlative in the waking world — a new wing of

our house, for example, which seems just as real as the house we know

in waking life. The impression of “reality” here does not depend

on any shared ontological identity between the imaginary wing and our

dream experience of it. The mechanical authority of the camera

does not figure into the equation, and yet the imaginary wing feels

just as real as the spaces of waking reality. Our dreaming mind

convinces us of this reality without any forensic corroboration.

It is the impression of space alone which links photographed cinema

with animated cinema. Photography and animation are merely

techniques for creating illusions of space which we can imaginatively

enter as wholly and as confidently as we enter the spaces of dreams.

Bazin argues that shots need to convey a sufficient impression of

“realism” to counteract the enervating tendency of montage, which

again is a profound insight, but fails to account fully for the dual

nature of some “metaphorical” editing. When Hitchcock cuts from a

shot of Cary Grant and Eve Marie Saint embracing on the train at the

end of North By Northwest to

a shot of the train entering a tunnel, the intellectual aspect of the

visual pun is clear enough — but both shots are interesting and

powerful plastically, both deliver a visceral impact, so that we can

not only comprehend the meaning of the shot of the train rationally

(as a pun) but also feel it as a physical evocation of intercourse.

Finally, Bazin's evaluation of montage does not fully take into account

the musical effects which editing can create. I would agree with

Bazin that such effects only have true power when the images involved

have an intrinsic plastic power of their own. We have all seen

those “experimental films” in which indifferent images are cut to the

rhythms of a piece of music — their effect is thin, superficial, the

correspondences between the rhythms of the music and the rhythms of the

editing merely mechanical, an exercise in redundancy.

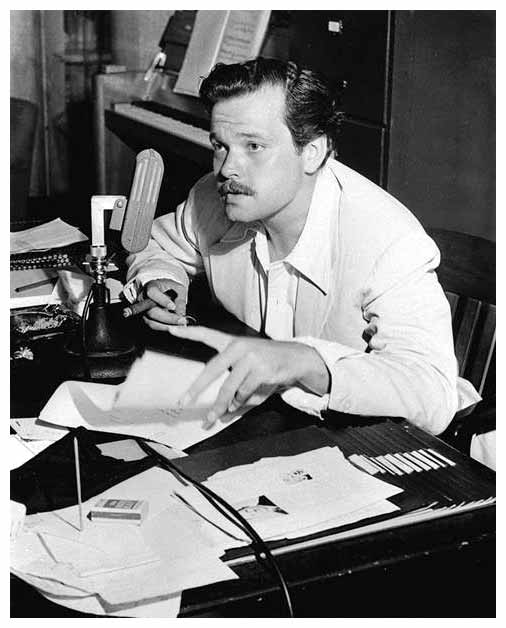

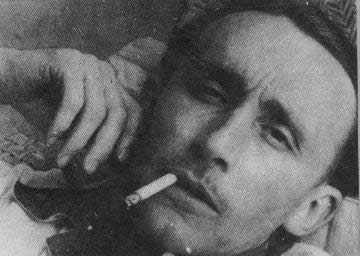

But consider the musical rhythms of the editing in Orson Welles' Falstaff.

The images, however fleeting, are always powerful plastically,

viscerally evoking space, but the editing gives them a new musical

quality — much the way the rhythms of poetic meter confer a

meta-meaning above and beyond the literal meaning of the poet's words.

My arguments with Bazin here are narrow but important, I believe.

If I were speaking with him today, face to face, as I sometimes feel I

actually am, so vivid is his presence in his writing, I would urge him

to cut loose from his attachment to photographic “realism” and

concentrate on the imaginative uses of all illusory space in cinema,

however it's achieved, and to think again about the ways illusory space

can be enlisted in the service of montage, not just as a kind of

compensation for the intellectual reductionism of montage but as a way

of investing montage with an über-cinematic artistic capacity all its

own.