There is a smile of love,

And there is a smile of deceit,

And there is a smile of smiles

In which these two smiles meet.

There is a smile of love,

And there is a smile of deceit,

And there is a smile of smiles

In which these two smiles meet.

Fox home video has been releasing a lot of terrific DVDs in their Fox Film Noir

series — great transfers of entertaining films with generally

excellent commentaries and brief featurettes about the movies and their

creators. They're running out of films from their vaults which

can plausibly be called noir — except that these days, apparently, just about anything can plausibly be called noir.

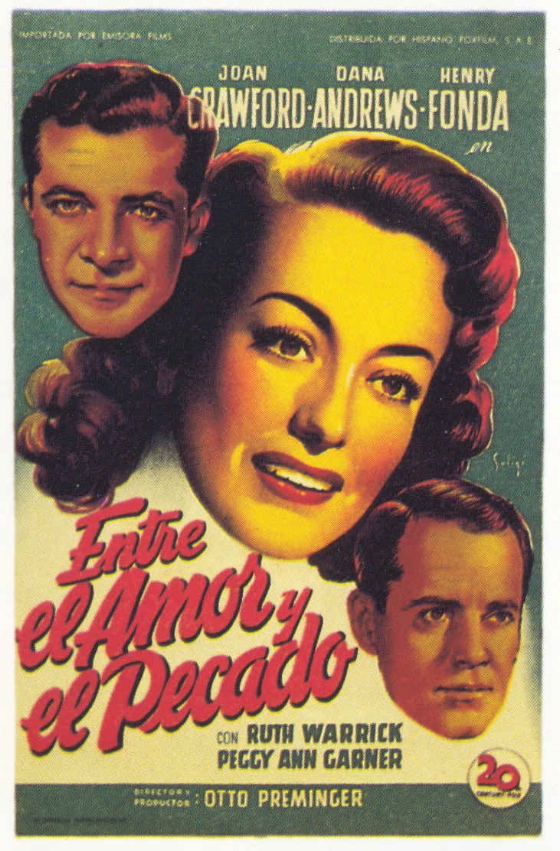

Daisy Kenyon, the 23rd title in

the series, is an extremely interesting film by Otto Preminger from

1947 which could plausibly be called domestic noir,

though it doesn't involve crime or violence in any significant

way. It's basically a soap opera centering on a very complicated

love triangle, but it's disturbingly dark, in ways that wouldn't have been

conceivable in Hollywood before WWII.

Joan Crawford plays a career girl in New York who's having an affair

with a married man, played by Dana Andrews, a charming self-centered

lout. Neither character seems to feel any moral qualms about the

affair, and Preminger presents it with an almost cynical nonchalance

that's strikingly adult and modern.

Crawford meets an equally charming but somewhat unstable returning war

vet, played by Henry Fonda. Fonda's character feels that the

world and everyone in it has become dead, and isn't sure if this

feeling has to do with the loss of his wife in a car accident or with

his experiences in combat. The war, and its collateral moral damage, are also referenced in an off-screen subplot in which

the Andrews character defends a Nisei war vet whose farm was stolen

from him while he was off fighting for his country, heroically, in

Italy. He loses the case.

According to Preminger's biographer Foster Hirsch, these elements

were not prominent in the novel on which the film was based. It

was Preminger and his

screenwriter who chose to associate the moral confusions and neuroses

of the characters with the broader anxieties of post-war American

society, issues of guilt over the price of victory, over the

psychological wounds suffered by the soldiers who won that

victory. It's a theme one finds

in many noir and noir-inflected films of the time, sometimes explored explicitly, as it is here, sometimes only by implication.

Perhaps Preminger was too explicit. Daisy Kenyon

was a box-office disappointment. Without the cover of the

crime-thriller genre, elements of which figure to one degree or another

in most other domestic noirs, the film's investigation of post-war American angst may have cut too close to the bone for contemporary audiences.

The mood of the film is almost unbearably tense and unsettling,

eventually involving child abuse and a scandalous divorce trial played

out in the tabloid press. There had always been soap operas like

this in American movies, of course, but there was always a clear sense

of when moral boundaries were being crossed and what the consequences

would be. Daisy Kenyon plays out in a world in which moral boundaries seem to have been erased.

The Spanish title of the film translates as “between love and sin”

but the tale offers few clues as to where one stops and the other

begins. The romantic triangle is resolved at the end, more or

less, with everyone doing the “right” thing — but there's hardly a

sense of moral triumph. We feel that all the characters are going

to remain adrift in a morally ambiguous universe, trying to walk a line

that none of them can see clearly. This is noir territory, all

right, but strictly domestic, and explored primarily from the point of

view of the female protagonist, which distinguishes it from the classic

noir cycle.

Once a poster boy for bourgeois bad taste, Bouguereau is starting to

look more and more radical — certainly more and more bizarre.

The solidity of his angels here is uncanny. The wings of angels

in art are often merely symbolic — in this image they

seem like practical appendages, as necessary to flight as a bird's

wings. They give these angels a monstrous quality, as though

they're the product of some unholy genetic experiment. On the

other hand, it may be that the sight of real angels would produce the

same impression and that real angels, if photographed, would look exactly as

they do above.

For a lengthier meditation on the work of this extraordinary artist, go here:

Charlton Heston has died at the age of 84. In life he never got

the appreciation he deserved — damned with faint praise as an actor of

limited range, damned in more direct terms for his right wing politics

and defense of gun rights. As an artist, however, he was a

genuine hero.

It was Heston who lobbied Universal to give Orson Welles the job as director of Touch Of Evil

(above), at a time when no one else in Hollywood would give Welles the

time of day, and he single-handedly kept Sam Peckinpah on Major Dundee by offering to kick back his own salary into the production.

In movies, presence is sometimes more important than range — one might

argue that it's always more important than range — and presence

requires more than mere personality. It requires its own kind of

craft and courage. There was no other actor of his generation who

could have held his own in El Cid, and his “presence” helped make that film a masterpiece. It also elevated The Planet Of the Apes from a B-picture to a pop classic.

I am personally grateful to him for Touch Of Evil

— mangled as it was by the studio it's still one of the great American

films, and it wouldn't exist without the artistic heroism of Charlton

Heston.

And for those of you who can't get past his efforts on behalf of the NRA,

remember that he also stood with Martin Luther King, Jr. at the March

On Washington — one of the few Hollywood celebrities with the guts to

take a public stand like that in 1963.

Here's link, via Boing Boing, to a collection of Mike Wallace interviews from the 50s, including one with Gloria Swanson:

The Mike Wallace Interview Archive

Wallace's

technique was to get as close to insolence with his guests, especially

his female guests, as possible without crossing the line into

rudeness. The lack of respect he shows to Swanson is sickening

and she barely keeps her dignity intact. Swanson observes that

“something has gone dreadfully wrong with the American man,” and

Wallace, puffing away on a cigarette throughout the program, proves her

point.

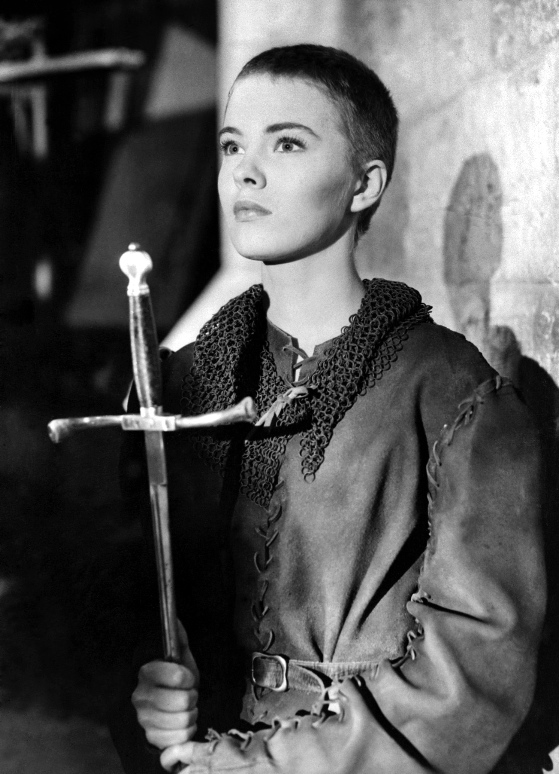

There's also a

touching interview with Jean Seberg, age 19, just after the disaster of

her performance in Saint Joan, her first film, in which Seberg, too, struggles,

somewhat more successfully, to keep her dignity in the face of

Wallace's insinuating smugness. “What will happen to your

career,” Wallace asks, “when it comes time for you to get married and

devote most of your time to your family?” “I hope I'll marry a

man who lets me continue with my career,” says Seberg, looking slightly

bewildered by Wallace's attitude.

The two great

stars, speaking from different ends of their careers, manage to make

Wallace's cigarettes look like accurately-sized phallic symbols.

What we're seeing in these interviews is the birth of modern

journalism, in which hacks try to elevate themselves by patronizing

their betters, treating their accomplishments as the same sort of

hollow flim-flam the hacks are practicing.

What we're also

seeing is further proof that modern feminism was a response not to an

over-powerful patriarchy, but to a patriarchy in full-on psychic

collapse. Wallace comes off here as a truly pathetic figure.

Frustrated by reports that the Clinton campaign is arguing to Super Delegates in

private that Barack Obama “can’t win” in November — presumably because

he’s black — some Obama surrogates have countered with the argument,

also expressed privately but widely reported, that Senator Clinton can’t win in November

because she’s an asshole.

The attempt seems to be to associate Clinton with unpopular Republican

Presidents who are generally seen as assholes — like Richard Nixon and George

Bush. Clinton supporters have been quick to point out that Bill

Clinton, still a popular figure in Democratic circles, was also an

asshole, but still managed to balance the budget and keep America safe.

Other Clinton backers expressed outrage over the Obama tactics.

“Hillary Clinton can’t help being an asshole,” said Governor Ed Rendell

of Pennsylvania, “anymore than Barack Obama can help being a

Negro. Criticizing a person on the basis of some inherent characteristic

demeans the public debate.” In response to questioning, Rendell

said that “Negro” was not a term he normally used himself, “though it

does reflect the language of many voters in my state, who may not be

ready to vote for a person they see as an uppity jigaboo. Naturally,” he added, “that attitude doesn’t reflect my personal views.” Reporters said that Rendell winked repeatedly at the camera during these remarks, though an aide later explained that the

Governor had simply gotten something in his eye.

CNN political analyst David Gergen warned that the Obama argument could

backfire. “Assholes make up a significant percentage of the

American electorate,” he said. “Naturally, they’re attracted to a

candidate who is also an asshole and sensitive to attacks on that

candidate, whom they perceive as ‘like them’. Barack Obama can’t

win the Presidency if he totally alienates the asshole vote, which

could determine the outcome in many swing states, like Florida.”

Obama’s only comment on the controversy — “American politics has no

place for assholes” — has struck many observers as ambiguous, at best.

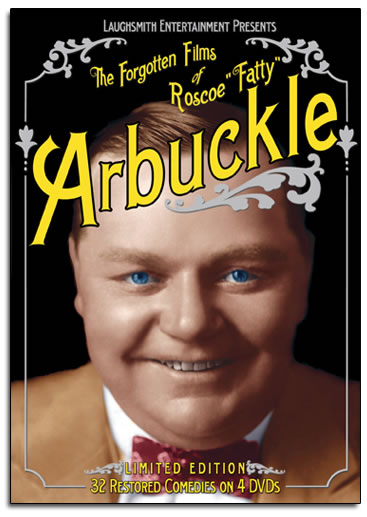

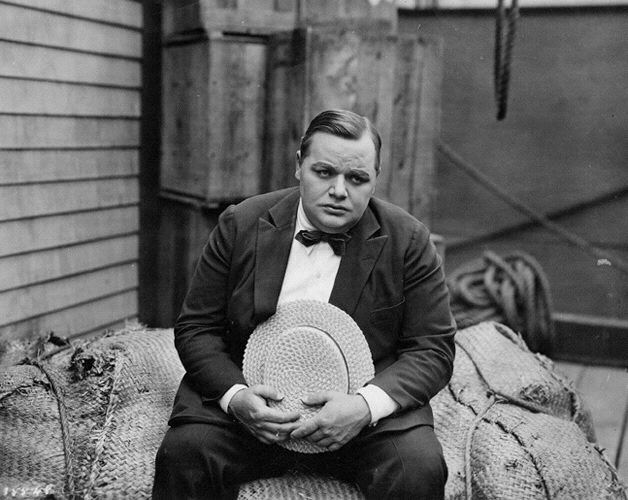

In 1920, Roscoe Arbuckle became the first great comedian of the silent screen to make a full-on transition from shorts to feature films. Chaplin had appeared in the feature comedy Tillie’s Punctured Romance as early as 1914, but under Mack Sennett’s direction and as a second lead. Chaplin wouldn’t release his own first feature until 1921. Buster Keaton starred in The Saphead in 1920 but he continued to make shorts after that until 1923, when his feature career began in earnest with Three Ages.

Arbuckle made nine feature films in the two years before scandal interrupted

his career, and never appeared in another. I believe that all but three

of them are lost, and the last two were never released in America, due

to the scandal. One of these, Leap Year, survives and is included on

the magnificent DVD set The Forgotten Films Of Fatty Arbuckle. It’s

absolutely fascinating.

In the earlier shorts offered in the collection we can see Arbuckle

transition slowly from the comic actor of the Sennett farces to the

full-blown silent clown of the Comiques. Chaplin and Keaton seemed to

have intuited almost from the moment they stepped in front of a camera

that the silent cinema was perfectly adapted to a fixed clown persona

— a character who could migrate from film to film yet still stay

essentially the same, with a way of moving, of being in space, that,

along with a few clothing props, singled him out as a distinct,

slightly hyper-real being, much like a circus clown or a figure from

the Commedia dell’ Arte.

Roscoe moved slowly from being a comic actor who did funny physical bits to

incarnating “Fatty”, the slapstick clown, and all along the journey he

was pulled back to the former mode. In the films he did with Mabel

Normand, character, especially as embodied in their relationship, took

precedence over slapstick — at least until the trademark Sennett

mayhem of the climax. In one of the Sennett films Roscoe directed, He

Did and He Didn’t, he takes this mode even further, edging into the

realm of upper-class drawing-room comedy, with very sophisticated

lighting and photography.

Until I saw Leap Year I would have seen this mode as a detour in Arbuckle’s

development as a comedian — a detour on the road to the Comiques,

where Arbuckle takes his place with Keaton and Chaplin as a classic

slapstick clown. Leap Year, though, totally altered my sense of what

Arbuckle was about. It’s as far from the universe of the Comiques as

it’s possible to get.

It inhabits, in fact, the universe of P. G. Wodehouse, whose gentle,

kindly satires of the young and well-heeled beautiful people of his

time were immensely popular in 1920. Leap Year perfectly captures the

sweetly daft world of Wodehouse’s slightly nutty, vaguely dimwitted but

immensely lovable trust-fund kids of the jazz age.

The miracle of it is that Arbuckle, knockabout comedian extraordinaire,

funny slapstick fat guy, fits so perfectly into this world. He does it

by simply behaving as though he’s Cary Grant in a romantic comedy, Fred

Astaire in a romantic musical — and because he doesn’t doubt it for a

moment, neither do we.

Roscoe plays the feckless nephew of a rich man, presumably the heir to a vast

fortune. This could explain part of the reason he’s so irresistible to

the women in the film — but not all of it. He’s a genuinely romantic

leading man. His sweetness and his physical grace sell us on that. He

just dances through the role.

The film doesn’t allow for much slapstick, but Arbuckle finds ways of

slipping it in delightfully here and there — most notably in a scene in which he’s

trying to convince his would-be brides that he’s having fits. The fits

are little masterpieces of physical comedy, as fine as anything Chaplin

and Keaton were capable of at their best.

But the performance doesn’t depend on these things, and the film remains a

frothy drawing-room farce. The farce becomes strained at times,

particularly towards the end, and the froth congeals a bit, but the

overall effect is of lightness and joy. It reminded me a little of

Murnau’s The Finances Of the Archduke from 1924 — particularly in

its use of the sunny Catalina settings of the film’s middle section, in

which the landscape seems to conspire in the fun, as the Dalmatian

coast did in Murnau’s film..

Was this really the sort of film that the mad surreal clown of the Comiques

wanted to make? He certainly seems to be fully committed to the work

and having a hell of a good time. Were the other Arbuckle features

anything like this? If Arbuckle’s career had continued on its natural

course, and he’d taken greater command over his films as a director —

where on earth would he have ended up?

This film expanded my appreciation of Arbuckle’s range and genius and

altered my sense of the comic landscape of films in 1920. It’s easy to

think of Arbuckle as an actor whose journey towards becoming another

Chaplin, another Keaton, was tragically diverted. But maybe he would

have become something else entirely — something we can’t even imagine,

because he wasn’t able to show it to us.

Jules Bastien-Lepage died tragically young, in 1884, when he was in his late thirties. He painted one masterpiece, Joan Listening To the Voices (above),

which now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

It's impossible to describe the effect of this large canvas, with its

complex and convincing illusion of space, which Joan seems about to step out of,

prompted forward by her visions. It's an example of a

photo-realistic technique enlisted in the service of mystical drama.

Bastien-Lepage groped about a bit in his short career, with stylized

works of grandiose ambition that seem clumsy and pretentious and

modest genre paintings that seem trite, but his über-photographic style

could occasionally produce miracles, like this extraordinary portrait of Sarah Bernhardt,

which has the quality of a bas-relief:

No other evocation of Bernhardt, in literature, art or photography,

brings us as close as Bastien-Lepage's portrait does to the charisma of

the great artist. Nadar's photographs of the young actress

humanize her, touch the heart — Bastien-Lepage's portrait records the

determined audacity of her genius. She seems powerful and

vulnerable at the same time, part of the alchemy of a star.

The American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens did a remarkable

bas-relief portrait of Bastien-Lepage in bronze, which makes a fine

pendant to Bastien-Lepage's portrait of Bernhardt — both have a

tactile grace that takes the breath away, both summon their subjects into

our immediate presence, obliterating time and mortality:

Yesterday, Showtime screened a rough assembly of Orson Welles' legendary uncompleted film The Other Side Of the Wind,

which Peter Bogdanovich is restoring for the cable channel. The

select group of critics in attendance were stunned to find that the

film bore no relation whatsoever to the brief excerpts from the film or

to the script pages which have previously seen the light of day.

The film unveiled was in fact a shot-by-shot remake of Citizen Kane using sock-puppets in place of the original actors. Citizen Kane

is considered Welles' masterpiece, and many have pronounced it the

greatest movie ever made — a stunning debut which Welles never managed

to live up to in the course of his subsequent career.

Bogdanovich explained the “very Wellesian” ruse involved — “He shot

fake footage and wrote a bogus script to keep his real plans a

secret. 'Everybody wants another Kane,' he told me, 'so I'm going to give it to them. I'm going to shove it up their ass.'”

Bogdanovich believes that the sock-puppet Kane

will eventually be recognized as a greater work than the original —

“though it may take awhile. Orson was always years ahead of his

time.”

Bogdanovich hopes that the restoration of the Kane

remake will be completed towards the end of this year and screened by

Showtime in 2009. It will appear under the name Welles chose for

it shortly before his death — Kane You Believe It?

[Photo by Carl Van Vechten]

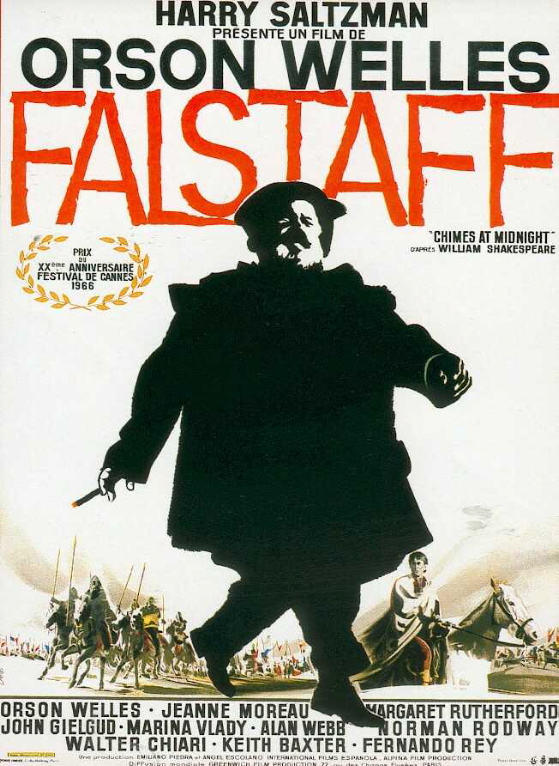

The

poetry of a play by Shakespeare is characterized by an almost

supernatural density of imagery and invention, wordplay, wit and

insight. Though designed to fly by in two hours' traffic

upon a stage it simply cannot be absorbed fully on a single hearing or

reading, composed as it is of a torrent of miraculous phrases and passages that

repay continual study. The sheer abundance, the sheer generosity

of it is overwhelming.

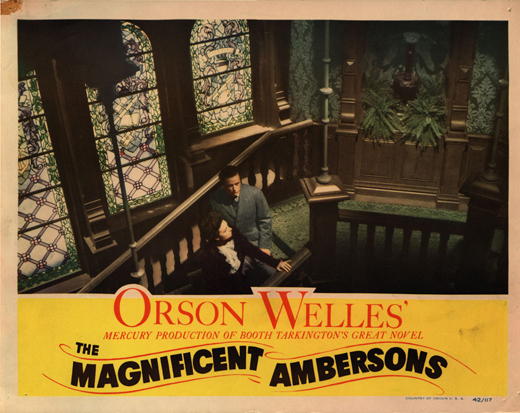

Orson Welles completed three films based on Shakespeare plays — Macbeth, Othello and Falstaff (Chimes At Midnight).

His interest, as it became clear over time, was not simply in mounting the plays within the cinematic

medium but pushing the medium to supply a cinematic equivalent to

Shakespeare's poetry. In Falstaff,

I would argue, he finally succeeded in this ambition. In the

process he completely rethought the approach to cinema he employed in

his early masterpieces Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons.

Citizen Kane, though

dominated aesthetically by scenes shot in deep focus and playing in

long takes, in fact employs a grab-bag of cinematic techniques —

process shots involving backscreen projection, models and matte

paintings, double-exposures, faked newsreel footage. In The Magnificent Ambersons,

Welles experimented with even longer and more elaborately choreographed

single-take scenes, some of which were cut up by Robert Wise at the

behest of RKO when they took the film away from Welles — but Welles

also included pictorial trick shots that violate the aesthetic of the

single-take scenes.

With The Stranger, Welles was

trying to work within the boundaries of a more conventional studio style,

but he eschewed trick shots almost entirely and included one long,

stunning single-take scene made with a crane on tracks in a forest. In The Lady From Shanghai

he tried his best to stick to location photography and to incorporate

long single-take scenes, but the film was so meddled with by Columbia

that we don't have a clear record of Welles's vision for the film as a whole.

All this was prelude to his first Shakespeare adaptation for film, Macbeth,

made cheaply and quickly for Republic Pictures. The 23-day

shooting schedule meant that Welles had to limit his technical

ambitions for the film. His increasing fascination with long

single-take scenes resulted in one extraordinary feat — a

10-minute shot which records the entire episode leading up to and including the murder of Duncan

and the arrival of Macduff, who discovers the crime. It plays

out on several levels of the studio set, covered by pans, tracks and

crane moves.

There are two other less extraordinary single-take scenes of some

length. One records the episode in which Macduff learns of the

deaths of all his “pretty ones”. This is taken from a fixed

camera position on a studio-exterior set without great spatial

interest. The four actors involved move about in ways that often

feel arbitrary in order to create different groupings of the characters

and heighten the complexity of the shot. The other shot records the

scene in which Macbeth, on the parapet of Dunsinane, learns of the

approach of Macduff and his armies and then moves inside to discuss

Lady Macbeth's mental health with her doctor. Again, the studio

sets here don't offer much spatial complexity and the choreography is not

especially dynamic.

Two shorter scenes involving dynamic camera moves are more

powerful. In one, the camera starts on a close-up of Macbeth, left

alone in the banqueting hall, and moves with him, pulling back, as he

races outdoors to the top of a rock and summons the weird

sisters. This is followed shortly by a high crane shot that swoops down

slowly onto the figure of Macbeth and ends in a close-up on his

upturned face.

The rest of the film employs a more conventional editing of shorter

shots. Some of these shots are visually arresting, involving

dynamic camera moves and angles, but many more are merely

utilitarian. There are a few interpolated shots taken on real

exteriors, a couple of shots employing matte paintings and, in the

final battle scene, a series of shots manipulated with optical

zooms. Taken as a whole, the visual strategy of the film is

chaotic.

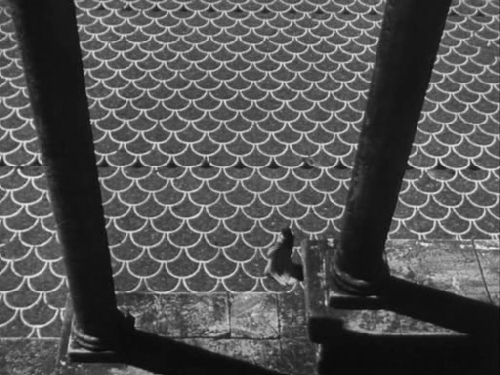

When he came to make Othello

a

few years later, Welles said he planned to shoot it all on built sets

and in long takes — making it, in effect, an extension of the approach

he took with the long single-take studio-bound scenes in Macbeth. He had been disappointed with the execution of the sets he designed for Macbeth, which do indeed look pretty cheesy most of the time — but he had a superb designer for Othello, Alexander Trauner, who sketched out elaborate sets for the film, meant to

be built at the Victorine Studio in Nice. Welles was thrilled

with the sets Trauner envisioned and always spoke of them wistfully in

later years.

All of Welles' plans for Othello had to be abandoned, however, when the film's

original financing fell through. Welles could only afford to

shoot in real locations, few of which were suitable for the entirety

of a given scene. In addition, limitations on equipment and the size of the crew

meant that he could not shoot long takes, which, as he explained,

require the technical resources of a large studio production unit.

These problems altered Welles' whole aesthetic approach to the film,

since he would not only have to use short takes more or less exclusively but he

would also have to match shots taken in disparate locations within a

single scene.

His response was masterful. He concentrated the full power of his

visual imagination on the individual shots — almost all of which, however brief, record

deep, dynamic spaces and boldly choreographed movement — and used rhythmic, musical editing in an attempt to unify them

into a coherent artistic whole.

The result was impressive but not uniformly successful. Clearly Welles was improvising

from day to day, sometimes desperately — the production was halted on numerous occasions when

funds ran out, necessitating changes of locale and the loss of actors

due to conflicting commitments. The “music” of the editing was

something Welles could not always control expressively — often he was

just trying to keep the beat, to bridge extreme gaps in continuity.

But necessity had led him to new possibilities of invention. He would deploy them spectacularly in Falstaff.

In that film he would shoot to the music of the editing he

envisioned, without the technical vexations created by Othello's near-fatal financial emergencies. There would be no long, virtuoso single-take scenes

but each shot would be dense, beautifully choreographed, with its own

dynamic spatial complexity. These shots would be utterly

involving in themselves

— and Welles would be able to preserve a sense of spatial continuity

from shot to shot to a degree that had not been possible on Othello — but the images would flow by with a relentless momentum, regulated by the metric of the editing.

Welles would not linger on the rich poetry of his individual shots but

race through them — as Shakespeare races through the rich poetry of his texts.

The great battle scene in the film offers the most extraordinary

vindication of Welles's approach. Though made up of scores of

short shots, each is like a film within a film — bold, dynamic,

involving. You feel you could linger on every one of them

indefinitely.

When he was 19, Welles wrote this about Shakespeare — “His

language is starlight and fireflies and the sun and the moon. He

wrote it with tears and blood and beer, and his words march like

heartbeats.” It's not too much to say that in the images of Falstaff Welles found a cinematic equivalent to Shakespeare's poetry — a true visual complement.

Which is to say that Welles took cinema as far, or nearly as far, as Shakespeare took the

English language — and that's as far as anyone has ever taken it.

This image enchants me in a delirious sort of way.

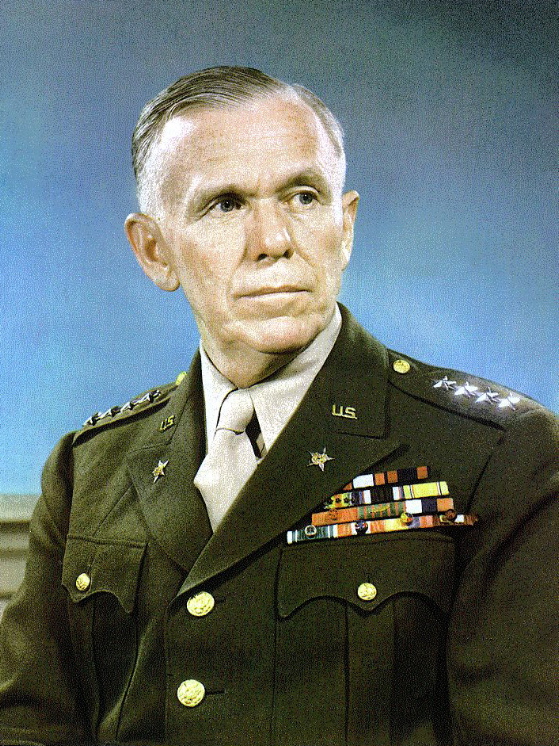

George Marshall was one of the greatest of all Americans — the

organizer of victory in WWII, the rebuilder of Europe after the war,

the only professional soldier who has ever won the Nobel Peace Prize.

He was also the most boring of great Americans, a man who never sought

glory, who concentrated on practical matters, who made the glory of

others possible. But he was a deep thinker about war.

“Military power wins battles,” he said, “but spiritual power wins

wars.” He was the anti-Rumsfeld. Two weeks after America

entered WWII Marshall set up a commission to plan for the occupation of

Germany and Japan, realizing how easy it would be to win the war but

lose the peace, as we have done in Iraq. In 1945 he urged his

generals to end the war as quickly as possible, afraid that extending

our government on a war footing, with its attendant centralized wartime

powers, would erode America's habits of democracy.

We need to remember him now — remember what our country has forgotten

in its “war on terror”. Our only hope in this war is spiritual

power.

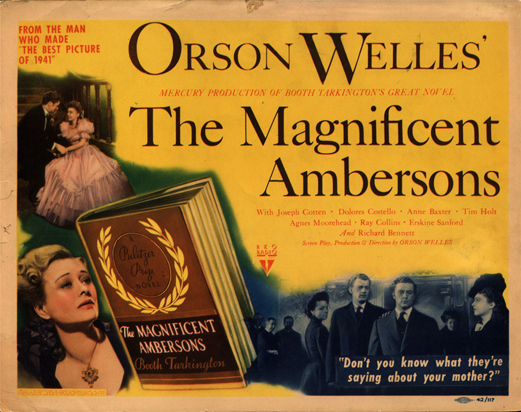

Here's some interesting and possibly hopeful news from Wellesnet,

the invaluable web site resource for all things Orson Welles. It

seems that Beatrice Welles, Orson Welles' daughter and one of his

heirs, made a legal claim against Turner Entertainment over the rights

to The Magnificent Ambersons and a couple of other films. Court documents tracked down by Wellesnet reveal that the claims with regard to Ambersons have been settled. This may explain why Ambersons

has not yet appeared on DVD in the U. S. and may be a sign that it will

be coming soon. Let's hope. This is one of the greatest

films not

yet available in the format in this country. Others are:

Greed

The Big Parade

The Merry Widow (silent version)

The Wedding March

City Girl

Falstaff (Chimes At Midnight)

Comanche Station

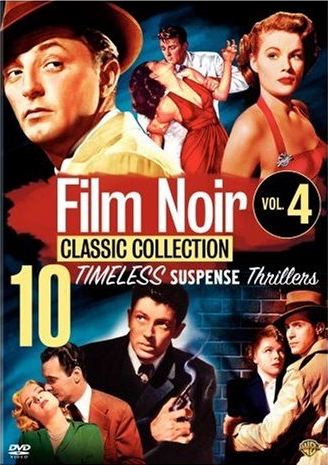

Volume 4 of Warner's Film Noir Classic Collection

is currently on sale for $29.99 all-in from Amazon — no sales tax, of course, and no

shipping charges (if you choose Super Saver Shipping). Ten films,

all interesting, including several noir classics and one masterpiece, They Live By Night — for less than $3 a film. Entertainment doesn't get much cheaper than this.

[Photo © 1960 William Klein]

An excerpt from a 2000 profile of Jean-Luc Godard by Richard Brody in The New Yorker:

During our interview, Godard referred

to the New Wave not only as “liberating” but also as

“conservative.” On the one hand, he and his friends saw

themselves as a resistance movement against “the occupation of the

cinema by people who had no business there.” On the other, this

movement had been born in a museum, the Cinémathèque: Godard and his

peers were steeping themselves in a cinematic tradition — that of

silent films — that had disappeared almost everywhere else.

Thus, from the beginning, Godard saw the cinema as a lost paradise that

had to be reclaimed.

If love of the silent cinema doesn't point the way to new, revolutionary

work — as love of ancient Greek art sparked the innovations of the

Renaissance — then it's just hobbyism.

In other words, silent cinema can be alive as a cultural force, as it

was for the young French cinéastes of the Fifties, just as ancient Greek

art was alive for the artists of the Renaissance.

The parade has not gone by.