. . . to think about Fay Wray.

. . . to think about Fay Wray.

Today

Bill Clinton mused wistfully about how nice it would be to have a

Presidential race in November between two candidates “who love America”

— meaning his wife and John McCain. It was a statement whose

unspoken but unmistakable premise was that the the third possible

candidate in November, Barack Obama, is someone who doesn't love

America.

Hillary has almost no chance of winning the Democratic nomination, and

therefore almost no chance of becoming President. Her thinking

seems to be that if she can't have the Presidency, then no Democrat

will. She's already suggested that only she and McCain are

qualified to be commander in chief. Now her husband is riffing on

the right-wing radio notion that Obama is not a true, patriotic

American.

The

moral decay of the Clintons has become positively rancid — it's

starting to stink up the whole body politic. Don't they have any

friends who'll take the keys away from them before they drive their car

over a cliff, dragging the entire Democratic party down with them?

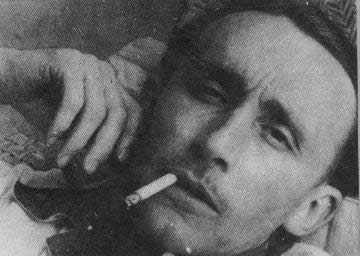

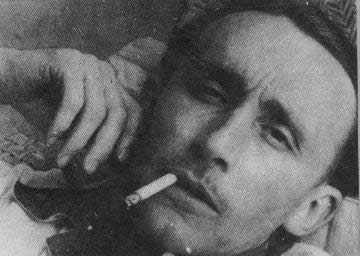

[The lovely portraits above are by the great caricaturist Thomas Fluharty, whose web log Amazed By Grace

says that he's not interested in being the best artist he can be but

only in glorifying God and his son Jesus Christ. Check it out for

some wicked-amazing art work and some fervent Christian proselytizing — a

strange combination. And thanks to the wonderful web site Potrzebie for directing me to Fluharty's work. Fans of Mad Magazine will understand where Potrzebie is coming from.]

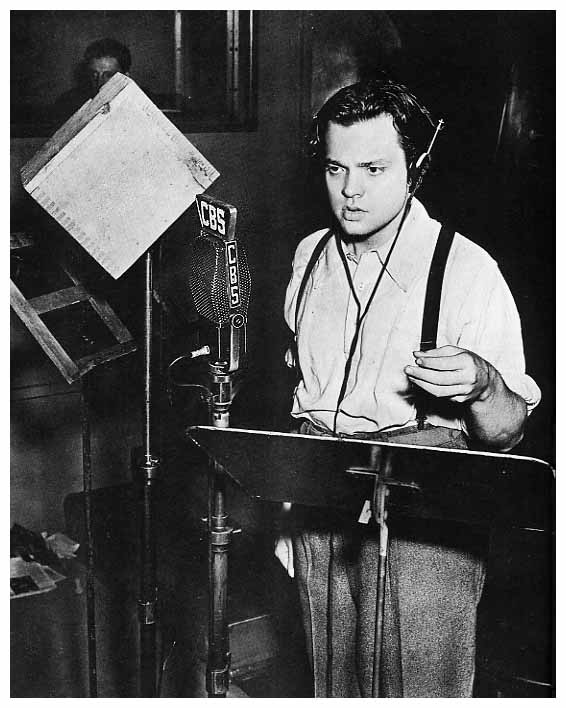

Below are my nephew Harry's notes for an oral presentation on Citizen Kane for his 9th-grade history class:

February 26, 2008

Citizen Kane

Intro Facts:

-Directed by Orson Wells in 1941.

-He also starred in , co-wrote and co-produced it

– all at the age of 24

-Previously, had been in radio, creator of the famous War of the Worlds episode for Mercury Theater in N.Y.C.

-Citizen Kane= the first and last major studio film over which he would have total control.

-Considered universally to be one of the greatest films ever created

Some Elements that make this film revolutionary:

-use of depth of focus shots (=wide angle lenses to capture the details

of the foreground, middle ground and background without prioritizing)

-depth of focus important because it allows the viewer to actively

investigate the space, make conclusions, see relationships between

characters and their space in more complex ways, spectator is an active

participant in the scene

-use of ceilings and the “fourth wall” = more interesting camera angles, more creative lighting , more real

-camera is inquisitive, as if it is a character itself, instead of a stationary machine that records what’s in front of it

-non-linear storytelling

-narrative told in bits and pieces, out of chronological order

-some scenes are revisited more than once from different perspectives

-story of Kane’s life is revealed as a reporter interviews people who

were closest to Kane in attempt to learn meaning of Kane’s last dying

words

-leads to a richer, more complex portrait of a person

Conclusion:

-On initial release, film was hated by most major film studios.

-Negative was almost burned

-Wells was persecuted by newspaper tycoon William Randolf Hearst, who

saw unflattering parallels between himself and Charles Foster Kane.

-Wells was blacklisted in Hollywood

-Citizen Kane was never distributed to major commercial theaters

-Sad because this movie defines us – what drives power, materialism, and what we may have lost on the way

After Harry's presentation his teacher said, “We always hear that Citizen Kane is one of the greatest movies ever made — now we know why.”

My notes on the notes:

A superb summary — excellent stylistic and thematic analysis. I

personally wouldn't call any of the stylistic elements of the film

“revolutionary”, however, since they had all been used before — just rarely

with such brilliance. It's true that most studio heads hated the

picture, because it offended Hearst and they were afraid of him, but

the Hollywood community recognized its brilliance — it was nominated

for several Academy Awards and won in the category of Best

Screenplay. The negative was indeed almost burned — Louis B.

Mayer offered to buy it from RKO and destroy it, as a favor to Hearst and to

protect the industry from his wrath. Welles wasn't exactly

blacklisted in Hollywood — it just became hard for him to work as a

director there after his first two films, and a third which he

produced, tanked at the box office. Kane

was distributed erratically and never got a chance to prove itself

commercially but it did play at a few major theaters in major cities —

it had its Los Angeles premiere at the El Capitan, which is still

standing. The El Capitan wasn't the most prestigious house in

town but it was a respectable venue.

Conclusion:

Well done, Harold!

It has sometimes been suggested that Barack Obama “transcends race”

— or that he's selling the delusional notion that America has

transcended race. I

think the truth of it is quite otherwise — that one of the deepest

unspoken appeals of Barack Obama, to all Americans, has been the

sneaking suspicion that one day he was going to speak

about race directly, open up the honest conversation about race which

this country has been too confused and too frightened to have. It

makes him slightly dangerous but also utterly intriguing.

I always assumed that he would say what he had to say on the subject

after he was elected President, and perhaps he made the same

assumption, but the Reverend Wright controversy made it necessary to

say it sooner rather than later. So on 18 March, within hailing

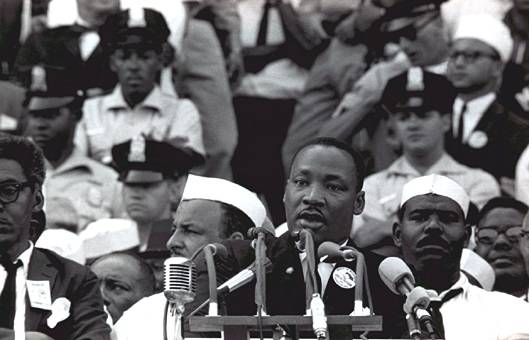

distance of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, he gave the most

important

speech on race delivered in this country since Martin Luther King's

address from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to the crowds gathered

for the March On Washington.

At this point I don't think it matters how people respond to Obama's speech

as a bit of political strategy, how it may hurt or hinder his campaign

for the Presidency. It's a speech that will echo down the

years. Curiously, for a man who is both praised and condemned for

emotional rhetoric, the speech was most notable for its sober and sobering

analysis of the state of half-conscious or unconscious racial division

in the country. There were no sweeping appeals to idealism, no

sense that the division could be repaired by lofty slogans, by “dreams”.

He told us where we are — where, on some level, we all know we

are. He gave us permission to speak about the issue from where we

are. He brought the talk around the kitchen table into the public

square. Nothing but good can come of it.

We may draw back from him, as a candidate, decide once again that we're

not ready to have this conversation. But we won't be able to stop

it now. William Blake said, “Truth can never be told so as to be understood, and not be believ'd.” That's why prophets get

stoned to death — for starting uncomfortable conversations that can't be

stopped. That's also why we need prophets and cherish them, if only in retrospect.

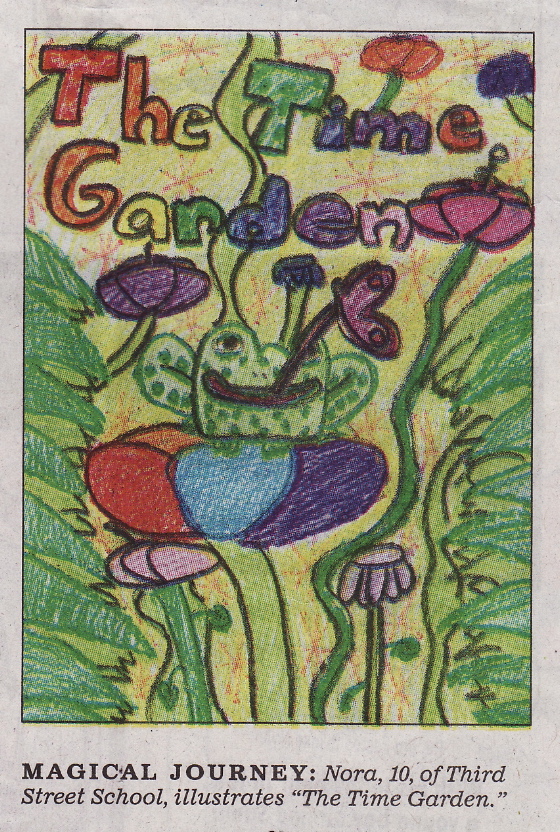

The Los Angeles Times published a book review by my niece Nora, age 10, in their Kids' Reading Room section on 2 March. (That's Nora in the green shirt, above, screaming on a roller coaster.)

Here's her review . . . of Edward Eager's The Time Garden, with the illustration she did to accompany the review:

The minute I looked at the

title I thought it was just another fairy tale, but boy, was I wrong!

This is a marvelous story. One sniff of the thyme and the magic begins.

Eliza, Ann, Roger and Jack find the Natterjack (a creature in a

frog's form) and run off on an amazing adventure through time and

space. They find out what really happened long ago and save people just

like them. Any boring day can be turned into an astounding journey if

they go into the garden. People of all ages, kid or adult, will want to

be in the magical adventures.

I love Edward Eager's books and have since I was a kid. His Knight's Castle is one of my favorite books of all time. I gave Nora her first Edward Eager book last summer, Half Magic, and now she's read them all. You should, too.

I recently finished Joseph McBride's excellent (and massive) biography Searching For John Ford. It tells you everything you want to know about the man . . .

except who the hell he was. The mysteries and contradictions of his

character simply cannot be sorted out. I'm sure the same would be true

of Shakespeare if we had massive documentation and testimony about his

life. The depth of the work in each man's case comes out of the

mysteries and contradictions and transcends them but sheds no light backwards on the

man himself. Perhaps, to be a truly great dramatist, you have to

abandon all hope of a coherent self in real life.

The biggest revelation in the book, to me, was the extent of Ford's

WWII service, which was far greater than I realized — but even in that

arena, nothing he did seemed to satisfy him. He told outrageous

lies about his wartime service, even when the things he actually did

were far more impressive. Reading the book makes one more and

more convinced that Ethan Edwards comes as close to a portrait of Ford

the man as we will ever have — a psychotic searcher who does heroic

things that no one else can do, and then wanders off alone, permanently

lost.

It's a sad tale but also, in some mysterious, unaccountable way, inspiring.

Follow this link to the second in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin . . .

I'm a person with too many T-shirts — way

too many T-shirts. Periodically I make vows not to buy any more

T-shirts, but sometimes you just can't help yourself. Two years

ago, on a visit to Memphis, Tennessee, I couldn't resist buying a

T-shirt from Graceland, from the Sun Records studio and from the Stax

studio.

Recently I broke down again. I bought two T-shirts featuring the

work of Fletcher Hanks, the worst comic book artist of all time, and

one featuring the work of Amy Crehore, a terrific painter (the design

is featured above.)

I really don't see how anyone could resist buying these T-shirts, so at the risk of enabling other people with T-shirt acquisition problems

I will add that the Tickler T can be had here and the Hanks Ts

here. May I also remind you that T-shirt should always be spelled

with a capital T, because only the capital T reflects the shape of the

shirt. A t-shirt would be some kind of turtleneck T.

Orson Welles once said that if any one of his films would qualify him for entry into heaven it would probably be Falstaff (also known as Chimes At Midnight.) As credentials for salvation go, Falstaff is probably as impeccable as any — it’s one of the greatest movies ever made, so great that it almost seems to inhabit a new medium all its own.

Visually it’s a torrent of dense, lyrical, consistently exhilarating images — an explosion of plastic invention unequaled since the days of silent cinema. But it’s a talkie, and its words are not just any words — they’re the words of Shakespeare. It’s not too much to say that Welles’ images, with their musical rhythms of movement within individual shots and from shot to shot, constitute a co-equal element with Shakespeare’s poetry. Image and word fly, dance, crack, soar and sing together. There has never been anything quite like it.

The soundtrack has technical flaws, however, which make it hard to appreciate the full scope of Welles’ achievement. The production was beset with severe financial problems — almost all the dialogue had to be dubbed, and Welles had to supervise the re-recording at a distance. The line readings are uniformly superb but the sync is not always perfect and the “room tone” surrounding the dubbed voices is inconsistent and often disorienting.

I don’t know if the original sound elements still exist — if they do, modern digital technology could certainly be applied to correct the flaws, though it would probably cost a small fortune.

As things stand, one needs to accept a slight disconnect between image and dialogue — which is no more than saying that the Parthenon has sustained a bit of damage through the years. One makes allowances.

The film is not available on DVD in this country. There is a barely acceptable all-region Brazilian edition in NTSC format which can be had online, but it’s not optimized for a widescreen monitor and the transfer of both sound and picture is mediocre. Still, if you’ve seen the film on a big screen, the Brazilian DVD can evoke the experience well enough.

I saw Falstaff at the Paris Theater in New York in the summer of my 17th year. During the battle scene my hair stood on end — I think I probably trembled with excitement. I know what cinema is, I thought to myself — the secret of it is here, in this film. It was more a gut feeling than a practical or intellectual insight, but the moment has inspired all my thinking about movies ever since. A hundred years from now people will still be studying Falstaff in an effort to apprehend the craft and mystery of movies.

Benjamin

Franklin said, “Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be

happy.” You probably know this already, and may know the famous

advertising line for Guinness Stout — “Guinness Is Good For

You.” In fact it is — incredibly good for you. A moderate

daily intake of beer has long been known to reduce stress and the risk

of heart attack but there are ingredients in beer that work many other

wonders besides lowering cholesterol, including reducing the risk of

cancer and cognitive decline (drink beer, stay smart forever!) and fighting off viruses. Beer also increases the

metabolism of protein, which is useful if the consumption of beer

causes you to neglect regular meals. (Hey, it can happen.)

And you thought your love of beer was based purely on moral

depravity. Not so, my friend! Far from it! A beer belly is the unmistakable sign of

a lifelong commitment to personal health.

Some anthropologists believe that grain was first cultivated by the human race not as a food source but

for fermentation into beer — bread was a happy by-product of the

activity. (The figures above are ancient Egyptians making beer.) This would mean that the entire advance of human

civilization, which was founded on the cultivation of grain, proceeds

from the desire to toss back some suds. The next time you're

enjoying a Bach Cantata or a play by Shakespeare or the sculptures of

the Parthenon, raise a glass to the good old boys and girls of 10,000 B. C., who got the party going . . .

. . . and cheers!

The second in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin.

The

one thing that defines the world of dreams, the spaces and the places,

the people and the creatures and the objects we find there, is that we

experience them as “real” — as having the substance and coherence of

the physical world we inhabit when awake.

It is only upon reflection after we awake that we realize how “unreal”

the dream world was we just experienced. We met the dead there,

perhaps, still alive, we discovered a new wing of the house we had not

known existed, we jumped and sprang twenty feet into the air.

We remake the waking world in our dreams in order to press it into the

service of emotional needs, but those needs would not be served if we

couldn't believe in the reality of the dream world. We may for

example feel, psychologically, in our waking life as though we are

being pursued by demons — activating primal fears of pursuit by

animals or persons intent on doing us harm. But we cannot see

those demons, which is disorienting. In dreams we give the demons

shapes, the shapes of real creatures, and thus ground ourselves in the

familiar. Of course we feel terrified by those tigers chasing us

through dream streets — they're tigers,

for God's sake, with claws and fangs. So much more reassuring,

paradoxically, than the unseen, undefined forces in waking life that

seem to be dogging our heels, bent on devouring us.

In dreams we reconcile the complexities of psychology with the

simplicities of the physical world. Dreams are a kind of

rear-guard action against advanced ratiocination, which takes us into

realms we cannot always comprehend fully or navigate.

This is not entirely a retrogressive process, since dreams re-orient us

towards the dynamics of the physical world, even if those dynamics as

they operate in dreams are not precisely aligned with the dynamics of

the physical world. There is a twofold consolation, a twofold

wisdom, in imagining psychological fears as physical threats within the

precinct of dreams. We

are, first, reminded that we live in a world of physical threats,

against which we must take precautions — emotional distress does not

obviate the need to avoid stepping in front of moving cars. At

the same time we

encourage ourselves to believe that psychological fears can be dealt

with as physical threats are dealt with — by fight or flight.

André Bazin believed that the “ontology of cinema” was rooted in the

absolute connection between the photographic image and its subject — a

connection similar to the connection between a death mask and the face

of a corpse, or a footprint and the foot that left it. This may

be an inescapable quality of the traditional still photograph, but the

source of the enchantment of cinema lies elsewhere — which is why

hand-drawn or computer-generated animation can be just as cinematic as

a photographically-based movie.

As long as a movie constructs a substantial and coherent alternate

reality it has the power to express and manipulate our emotions.

As long as it delivers the illusion of a world that is convincingly

real while we are inside it

a

film can mimic the process of dreaming. Cinema is not about, or

not only about, the mummification of reality — it is about the

translation of psychology into the realm of oneiric reality, and the

essential quality of oneiric reality is that it feels absolutely real.

Jean Renoir said that he saw Erich Von Stroheim's Foolish Wives at least ten times and that it was

the film which inspired him to dedicate his life to filmmaking. Renoir

said it impressed him with “the possibility of creating

within a film a world that might differ greatly from reality but still

would be experienced as having a wholeness and coherence like that of

the world we live in.” What else is Renoir describing but the world of dreams?

A lovely, mysterious image from Serbian artist Vladimir Dunjic (with thanks to Femme Femme Femme and apologies to Flann O'Brien.)

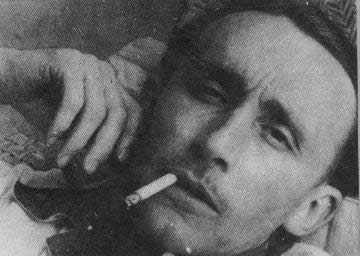

There

is simply no end to the wonders of the web. One I recently

discovered is a web site which hosts many of the radio plays Orson

Welles created before Hollywood scooped him up. These are

brilliant and extremely entertaining productions in which Welles

experimented with the aural effects he later applied to his movie

soundtracks.

Though they have a patina of “artiness”, and are often adaptations of

famous works of literature, the shows are aimed at a popular audience

— they blend the ambitions of Welles' innovative stage productions

with the lessons he learned as an actor on commercial radio. The result is popular art of a very high order.

On the site you can download many of the featured shows in MP3 format and listen

to all of them in streaming audio. Check it out here:

The Mercury Theater On the Air

. . . and thank Kim Scarborough, who created the online archive, for a signal service to our culture.

Follow

this link to an essay on the place of popular visual art in the

intellectual culture of the modern age — the first in a series of essays

dedicated to the great film theoretician André Bazin. I couldn't

find appropriate images to illustrate this essay and in any case it's

too long and serious to be a regular web log post, but some might find

it interesting . . .

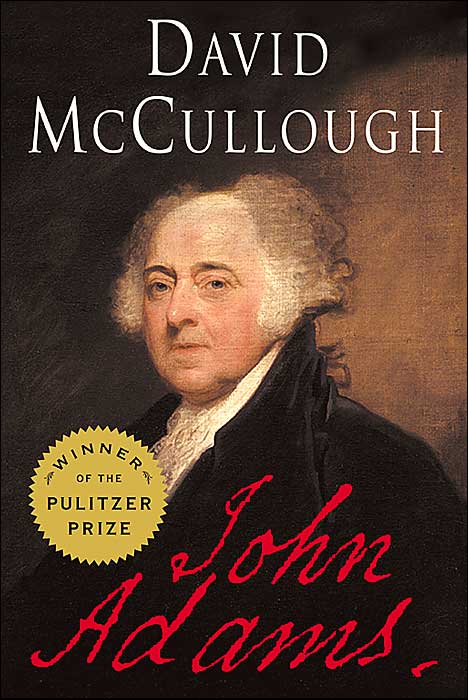

I commend to all my fellow citizens of this republic David McCullough's wonderful biography John Adams.

(That's Adams, bald and slightly pot-bellied, standing in the exact

center of John Trumbull's painting of the signing of the Declaration Of

Independence, above.) Erudite and sagacious the book is also

compulsively readable, magically evoking the physical world of the 18th

and early 19th Centuries but also bringing the men of the Revolutionary

era to vivid life.

The founders of the United States Of America were certainly the

God-damnedest collection of characters who ever collaborated on a great

enterprise. They seem mysteriously modern, perhaps because they

remain so recognizably American

— frank, down-to-earth, open-minded, industrious, optimistic . . . also pig-headed, venal and hypocritical

There were scoundrels and rakes among them, men of faith and skeptics,

simple farmers and grand seigneurs — but they were all so unaccountably radical in their devotion to the ideas (if not always to the practical realities) of liberty and equality, of self-government.

And they were brave. All the men above seen signing the

Declaration, many of them men of great wealth and position, would have

been hung as traitors by the English if their improbable revolution had

failed. They don't seem to have had the slightest doubt that it

was a risk worth taking, and merely joked about the jeopardy — as

Franklin did when he said, “We must hang together or hang separately.”

It can't really be explained, except as a result of something that had

evolved over many generations in the experience of living in the new

world, habits of self-reliance and independence which the Founding

Fathers explicated and guided but did not invent. Adams himself

knew this. “The Revolution,” he wrote, “was in the minds and

hearts of the people.”

Adams may have been the oddest of all the “indispensable men” of that

time — neither a soldier nor a politician of any particular skill, not

a great writer or thinker but possessed of an orderly mind and endless

energy, he had a personal independence of thought and an an

incorruptible integrity which made him the go-to guy in any crisis.

It was Adams who ensured the appointment of George Washington as

commander in chief of the Continental Army, Adams who procured loans

from the Dutch to keep the government afloat in the early days of the

Confederation, Adams who, in drafting the Constitution of the

Commonwealth Of Massachusetts, created a key model for the American

Constitution.

And it was Adams who served as America's first ambassador to the Court of St. James, received with honor as the representative of a new and independent nation by the same king who had once hoped to hang him.

The whole tale is surreal, unbelievable, but one loves Adams because he

didn't see it that way. He seems always to have believed that the

seeds of liberty, once planted in good soil, would bear fruit — just

as the seeds he sowed on his Massachusetts farm brought forth peas and

corn. At the end he was proud of what he had done for his

country, but he was just as proud of his farm.

Adams became President of course, for one term, after serving as George

Washington's Vice-President for two terms. He lost his bid for

reelection to his then arch-rival Thomas Jefferson, and became the

first President to hand over the reigns of power unwillingly, convinced

that Jefferson would ruin the new nation before it could fairly get

going. He groused about it, then jumped into a public stagecoach

and rode home, back to his farm, his peas and his corn. He bowed

to the will of the people without further complaint.

In that moment, the American experiment justified itself to itself and to the whole world.

Perhaps the strangest thing about looking at these old

revolutionaries today is that they always seem to be staring right back at us, at the American future we

now inhabit. In their regard there's hardly more than a trace of

self-satisfaction in what they accomplised, not a lot of sentiment, and

more than a little impatience. “We started this business well enough,” they seem to

be saying, “now get on with it.”

[I read the biography as a prelude to watching HBO's upcoming

mini-series taken from it, starring Paul Giamatti as Adams. This

strikes me as a brilliant piece of casting, Giamatti having a knack for

conveying the kind of adorable peevishness which many people observed

as a characteristic trait of Adams. The series will premiere on March 16.]