In 1947, an old, bitter, alcoholic has-been named D. W. Griffith

complained to a journalist that movies had lost something — “the

beauty of moving wind in the trees, the little movement in a beautiful

blowing on the blossoms in the trees” is how he summed it up. It’s sort

of an odd thing to say, since movies never stopped moving, and when

there are trees on screen you can often see the wind moving their

leaves.

But of course Griffith was talking about something more profound — harking

back to his own heyday as a filmmaker, when those moving blossoms were

not just a grace note, an accident of location, which might possibly

affect the taking of live sound, but in some real sense what movies

were about . . . movement, the illusion of movement in space, the

transformation of that illusory space, drawing us into it

imaginatively, investing it with emotional drama.

Griffith was bemoaning the loss of the discursive style of cinematic narrative,

in which the accumulation of passages of plastic transformation were

not simply the accouterments of style but the very method of

storytelling, of emotional communication, in film. He was bemoaning the

terrible efficiency of the studio method, in which those moving

blossoms became incidental decoration, garlands gracing the elegant,

ruthless machinery of narrative exposition.

Those of us who love Westerns love them in part because the Western genre

alone for many years after the coming of sound preserved that

discursive style — in which they way people and horses and things

moved and penetrated and transformed the spaces of a room or a street

or a landscape carried the burden of the drama, the narrative

exposition being pretty much formulaic and predictable.

Raoul Walsh, a Griffith protege, became a brilliant craftsman of the studio

style in the sound era, with an eye for plastic values which lifts most

of his work above the ordinary. But not far above the ordinary. His Sadie Thompson, from 1928, is a masterpiece, however — and a film

that in many ways defines the crossroads movies had come to in

Hollywood on the eve of sound.

Sadie Thompson is a very slick film, of great narrative economy — a studio

picture in that sense. But in scene after scene the narrative momentum

is suspended dreamily as we are invited to appreciate, to inhabit

intimate spaces and moments — to linger in them languorously. Swanson

plays a hardboiled dame, but we can sense the girlishness and innocence

that has survived her smarmy past — and Walsh takes time to let us

inside that quality of hers . . . not with a line of thought-balloon

dialogue, but in a rapturously lit scene at her window with O’Hara, in

which the way she looks at him illuminates her face from within,

absolutely breaks your heart. It’s like a movie within a movie, and

when you’re watching it, it seems as though this is what the whole

story is about.

Walsh doesn’t have a soundtrack to deliver the incessant noise of rain, so he

lingers on moments of transition between the wet outdoors and the dry

interiors, physical business with umbrellas and ponchos and damp

clothes. He luxuriates in exploring the fabulously atmospheric and

spatially intriguing inn set designed by William Cameron Menzies. He

rarely moves the camera, but when he does it has an emotional purpose

— Sadie being drawn into the interior of the island after she gets off

the ship, surrounded by the marines, O’Hara trying to carry her away

from Davidson and his creepy spell.

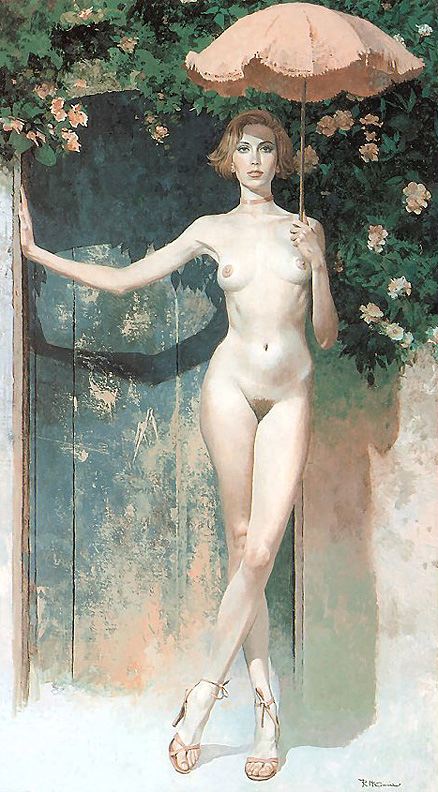

One of the most powerful moments is also one of the most subtle. Just before

the climax, Davidson looks down at the redeemed Sadie, slumped in a

wicker chair. She’s removed her make-up and straightened out her hair,

but still looks beautiful, in a severe way. Then Walsh pans down very

slightly from a close-up of Swanson’s face — just enough to let us see

her upper chest moving as she breathes. There’s no skin — we don’t

even see the curve of her breast under her dress — but the very

subtlety of the shift of attention is wildly suggestive and erotic. We

know exactly what Davidson is thinking.

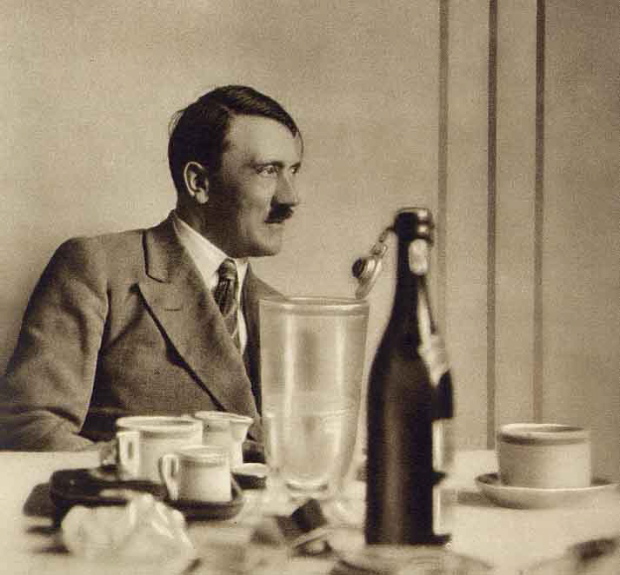

Lionel Barrymore, as Davidson, looking gaunt and somewhat terrifying, plays an

extreme character, but his performance is beautifully nuanced,

particularly at the beginning. We feel the sensual pleasure he takes in

tormenting sinners, which prepares us for his surrender to another kind

of sensuality at the end. It’s far more effective than Walter Huston’s

more tasteful and buttoned-up take on the character in the 1932 sound

remake.

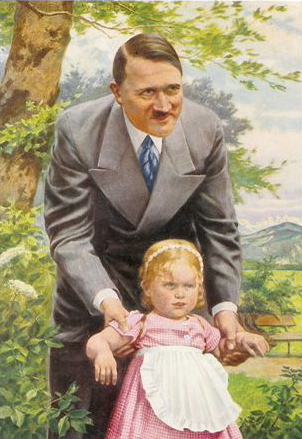

The simplicity and reserve of Walsh’s performance as O’Hara (above) serves the role well — he used his very inexperience as an actor to sell O’Hara’s shy, straightforward decency.

Swanson is brilliant — and brilliantly inconsistent. Her tough-girl swagger is

charming, and not entirely convincing, which makes her sweetness with

O’Hara, her innocent faith in his love, believable, and her sudden

breakdown in front of Davidson plausible as well . . . she was never as

hard and self-possessed as she seemed to be, and her first look into

the face of irrecoverable loss unhinges her completely. Joan Crawford’s

Sadie in the 1932 remake is a one-note impersonation by comparison, and

could have been played almost as well by a man in drag, which is what

Crawford sometimes suggests.

It’s a shame the last reel of the film has been lost — though the reconstruction of it on the Kino release is well-done and as satisfying as possible under the circumstances.

It’s a wonderful movie, with a foot in two different eras of Hollywood filmmaking, but with its heart and soul in Griffith’s.