When he died in a car crash this Spring, David Halberstam had just finished his 21st book, The Coldest Winter,

an epic study of the Korean War. It's partly a work of military

history, with combat narratives based on interviews with veterans of

the conflict, but its greater value lies in the way Halberstam places

the war in the context of the post-war world, of American and global politics and strategy.

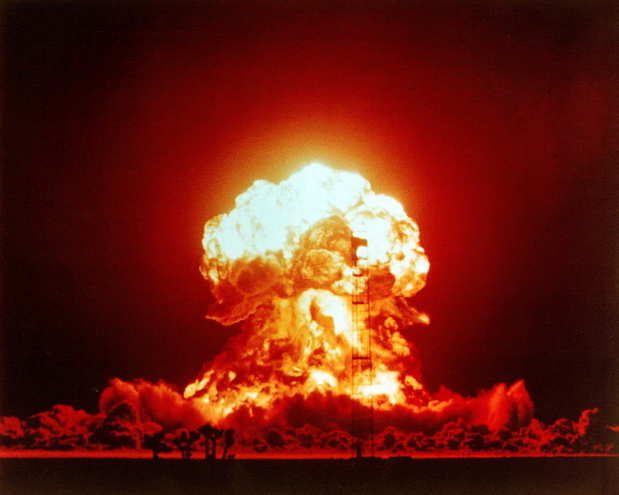

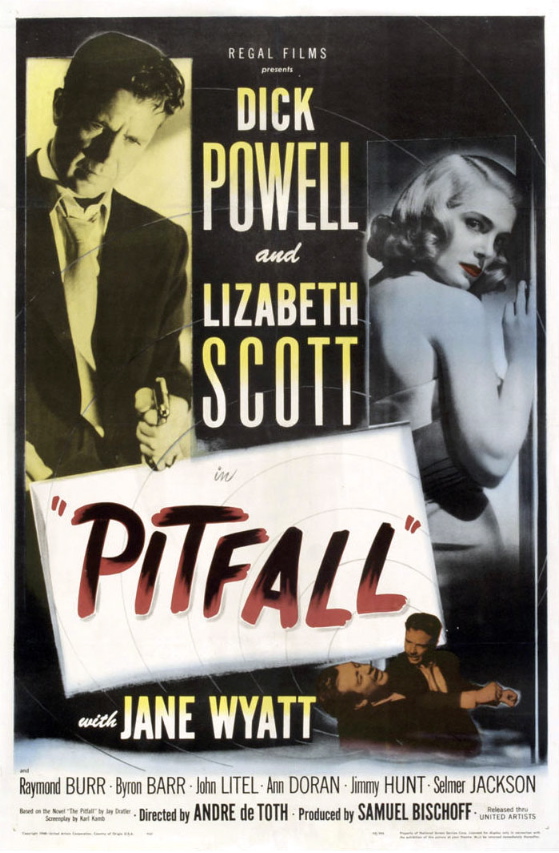

It fills in yet another piece of the puzzle of America's mood after

WWII — dark, anxious, bewildered, unsure of its new role as a world

superpower, veering between arrogance and lunatic paranoia.

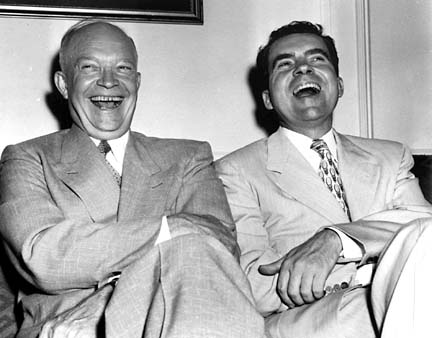

There are many lessons for our own times to be learned from the book —

not least about the ways the Republican party managed to box the

Democrats into policies they mistrusted under the threat of being labeled

“soft on Communism”. Substitute “terrorism” for “Communism” and

you will see the same dynamic at work today.

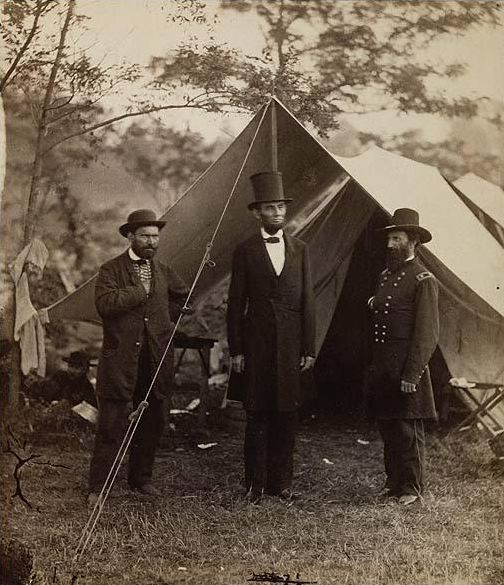

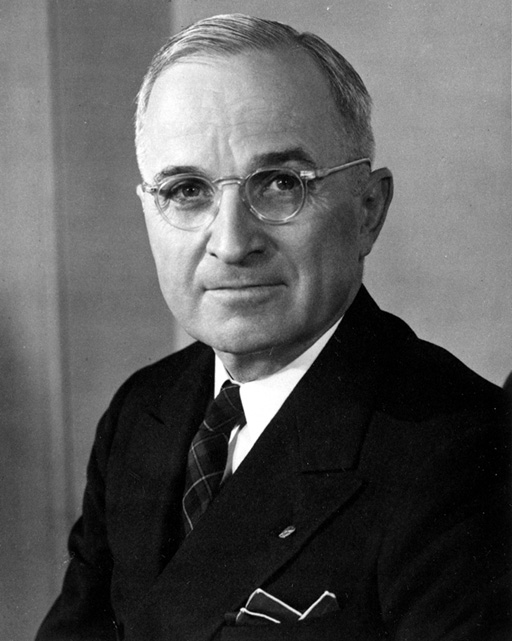

The war in Korea all but wrecked Truman's presidency, but he was

confident that history would judge him more kindly than his

contemporaries, as indeed it has. Among the high-ranking soldiers

and politicians, Matthew Ridgway and Truman emerge in Halberstam's book

as the true heroes

of the war. Ridgway learned how to fight the Chinese because he

was willing to take them seriously, to respect them as soldiers,

something the racist high command under MacArthur could not do.

Truman was willing to buck popular sentiment and

risk political ruin to oppose MacArthur, whose madness served the purposes

of the right-wing Republicans in Washington but whose insubordination

threatened the very core of the American system of government, the principle of

civilian control of the military.

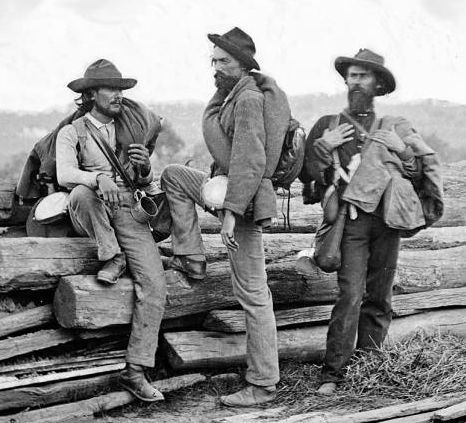

Among the boots on the ground, there were heroes by the thousands,

though they got no glory out of it, or even much recognition from the

folks at home. Korea was a war Americans wanted to forget, even

while it was happening — which is just the kind of war that needs to

be remembered and studied with care. We're in one like it

right now — part of the price a nation pays for forgetting the

grievous mistakes it has made in the past.