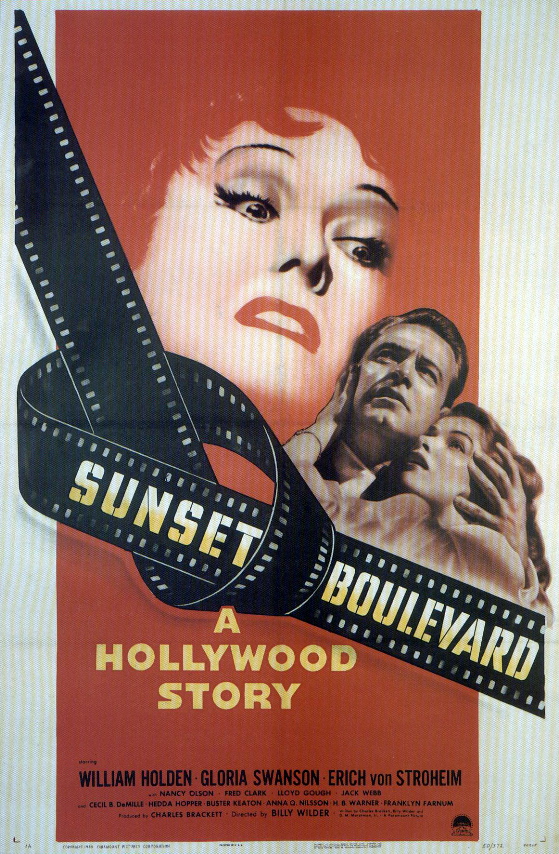

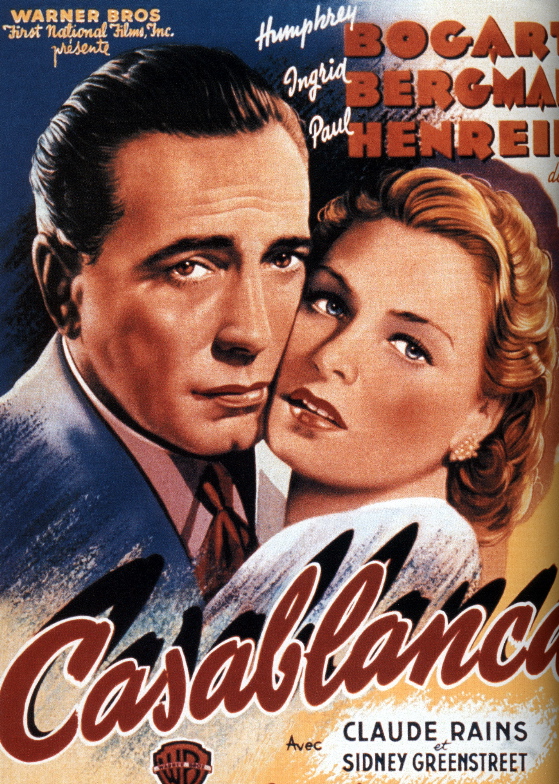

The term film noir was first used in something like its contemporary meaning in 1946 by French film critic Nino Frank. The occasion was a particular week in which five films made earlier in Hollywood but unavailable to French audiences during the war opened in Paris.

All of them had dark themes and reminded Frank of American pulp fiction from the 30s.

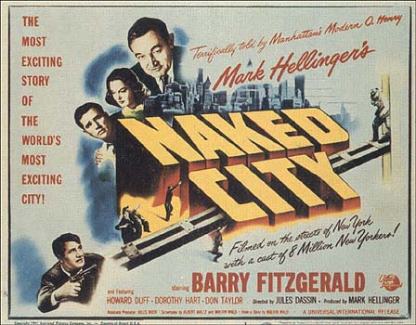

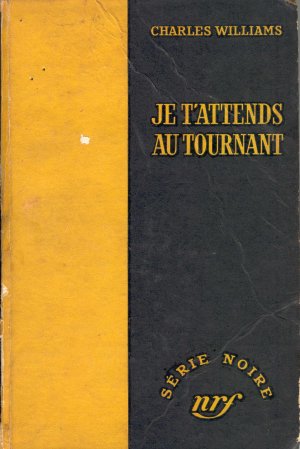

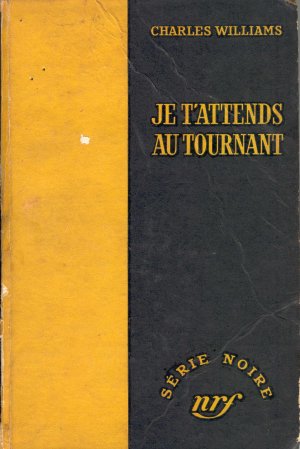

Much of this fiction had been published in France under the Série Noire (“Black Series”) imprint and so Frank, logically enough, labeled the five films films noirs. [The term film noir had earlier been applied to a series of moody, poetic French films from the 1930s which dealt with the travails of working-class people, but these had little in common with the crime thrillers Frank was talking about.] Three of the films, Murder, My Sweet (above, at the top of the post), Double Indemnity and The Phantom Lady were in fact based on the work of pulp fiction writers — Cornell Woolrich, Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain. The Woman In the Window, below, was more in the line of a Hitchcockian psychological thriller, a form Hitchcock had mastered before the war. Laura was a fairly standard murder mystery, a form that also predated WWII, though very elegantly executed.

In truth, there was nothing terribly new about the five films Frank called films noirs, though all were perhaps a little darker and edgier in tone than similar Hollywood films from before the war had been. Because the French had not been able to see the gradual development of this tone during the war years, it came as something of a revelation.

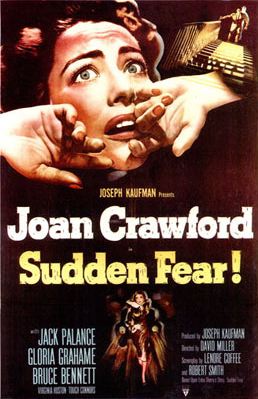

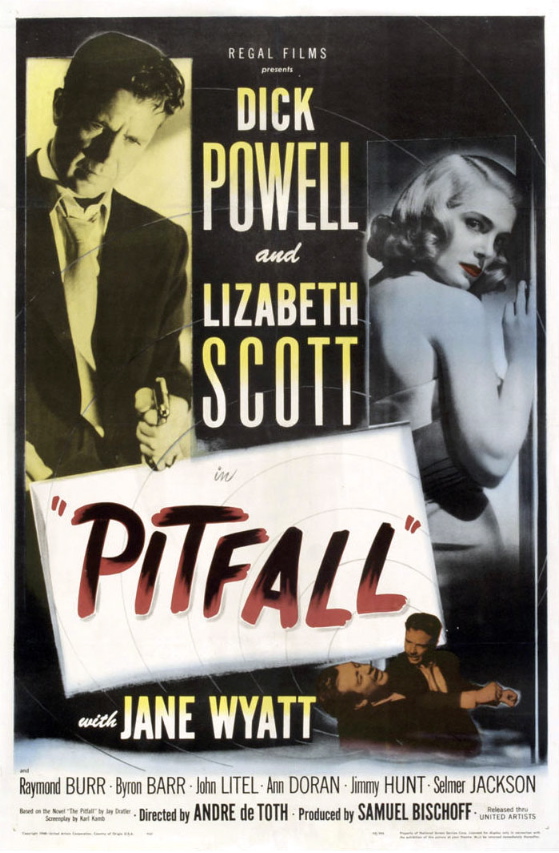

But after 1946 a new film tradition emerged which diverged from the hardboiled detective fiction of the 30s — and from the rancid domestic dramas of Cain and from the

Hitchcockian suspense thriller and from the classic murder mystery. It was a body of work which specifically addressed post-war, atomic age anxieties.

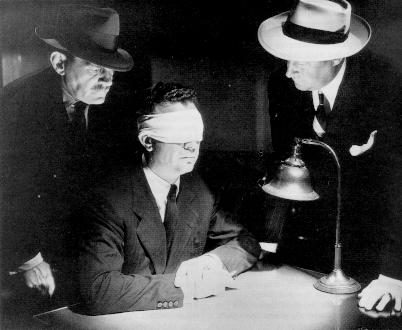

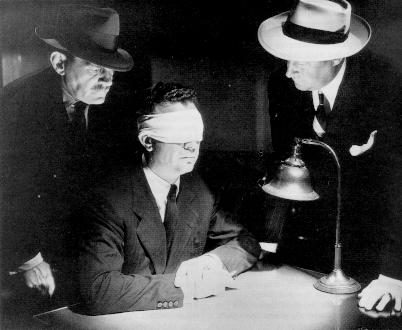

In this body of work, the underworld of pulp fiction seemed to have become the only world. Its protagonists were not wisecracking knights errant who ventured onto the wild side of things to solve a crime, nor were they everymen forced to brave an ordeal to become stronger and wiser, nor were they committed criminals, following transgressive urges to an inevitable and cautionary doom, a doom which restored society’s moral norms. They were men in a state of existential despair, unsure of how the world worked anymore, at the mercy of strong women, morally bewildered. The doom they often met with solved nothing, restored nothing. It was, in a sense, an expression of the post-traumatic stress disorder of the generation which had fought WWII and could never again see “normal” life in the same way again — especially not in the enduring shadow of nuclear annihilation.

This new tradition naturally enough inheirited the label film noir, even though it was quite distinct from the kinds of films that inspired Frank’s use of the label, the kinds of films out of which the new tradition emerged.

The imprecision of the term film noir was thus built into its history, so to speak. Most of the films we now think of as classic films noirs were made after the term was applied by Frank. They eventually came to constitute a distinct cycle, which flourished for more than a decade before it played itself out toward the end of the 50s.

I think the time has come to consider this cycle apart from the kinds of films that were first called films noirs — and I think the only sensible way to do this is to violate the history of the term film noir and to apply it only to the distinct cycle that emerged, for the most

part, after the term’s invention. In fact, I would argue that none of the five films that inspired Frank’s application of the term really belong to the tradition of the classic film noir.

In the interest of clarity and a sharper kind of analysis, we need to distinguish film noir

from the various traditions out of which it developed. [And we certainly need to distinguish it from the poetic proletarian French tragedies that were first called films noirs back in the 30s.] Pulp fiction, or hardboiled detective fiction, are terms that serve perfectly well to label the sort of films made from the works of writers like Chandler, Woolrich and Cain. Hitchcockian is a term that serves perfectly well to label the sorts of thrillers he specialized in. Murder mystery is a term that serves perfectly well to describe a film like Laura. The cycle of films that emerged after WWII, what might be called the atomic-age crime thriller, was something else again and it needs its own label . . . film noir.