There's a wonderful tribute to Godard and Karina and their masterpiece Vivre Sa Vie on the Film Forno web site. Check it out.

There's a wonderful tribute to Godard and Karina and their masterpiece Vivre Sa Vie on the Film Forno web site. Check it out.

[Photo © 2007 Paul Kolnik]

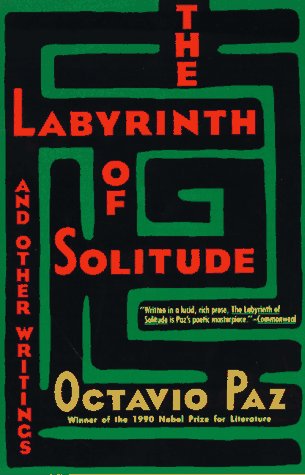

In his great book The Labyrinth Of Solitude,

Ocatvio Paz remarks that “architecture is a society's unbribable

witness.” If you want to know the truth about any society, look

at what it builds.

So what is the witness of Las Vegas, the most popular tourist

destination in America? As you sit on the terrace of a French

bistro, attached to a replica of Paris, and look across the street at an

evocation of an Italian lake, or down the street at a replica of New York,

or up the street at an evocation of ancient Rome, the message is clear —

“We don't know where we are.”

Everyone in America feels this, along the strip developments and in the

malls that all look the same, whether they're in Georgia or California

— even though they might not feel it on a conscious level, or admit it to themselves.

That's why they come to Las Vegas in such great numbers, and why they

love it. Las Vegas tells us the truth, let's us admit the truth

— we don't know where we are — and the truth is always

exhilarating. It makes you want to party.

[A note to readers: I apologize

for the site's being out of commission for a while — it exceeded its

bandwidth once again, even though my hosting service allowed me double

the usage I was paying for. They finally decided that I needed to

pay them more money — that now done, the site should be functional for the

foreseeable future. Thanks for the interest!]

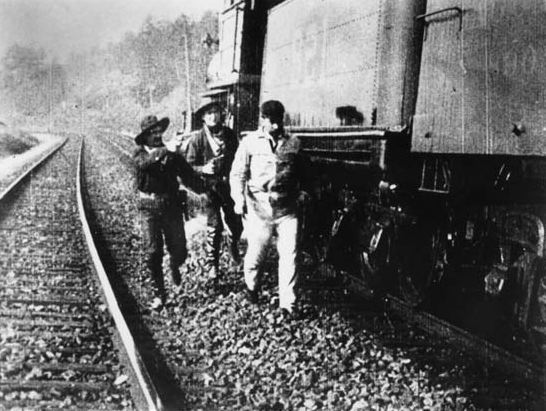

If you look at narrative films made in the first decade of the 20th

Century you'll be struck by a very odd aesthetic anomally. Scenes shot

out of doors will often be dynamically composed, emphasizing spatial

depth in the image — they look modern and can be extraordinarily

beautiful. Scenes shot on interior sets will, by contrast, be framed

head-on, creating the impression of a shallow space — this, combined

with the obviously painted sets, mostly using flats, looks decidedly

cheesy to modern eyes.

Why did audiences accept this violent contrast of cinematic practices

within the same film?

One reason, of course, is that the interior sets reminded audiences of

the stage, where painted sets and proscenium framing were familiar.

They could think of these scenes as filmed stage-plays, which is how

story-based movies were often defined and sold. The exterior scenes,

on the other hand, reminded viewers of pre-narrative cinema — the

“actualities”, short scenes of picturesque places and real events,

which were the primary content of movies presented as novelty

attractions.

These actualities tended to be agressively “cinematic”,

emphasizing the illusion of spatial depth to show off the magic of

movies — their ability to create the convincing illusion of a real

place on the other side of the screen.

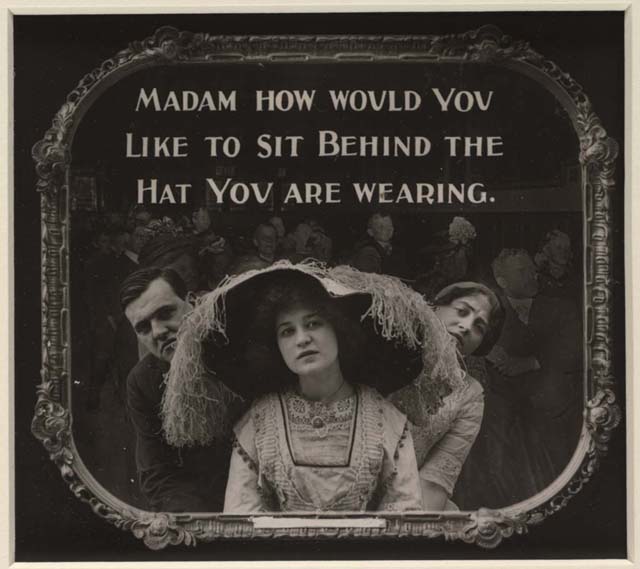

Novelty-attraction actualities were often part of a theatrical

presentation

which featured live performers as part of a variety bill — so viewers

were accustomed to an alternation of cinematic actualities with

theatrical stage-bound scenes.

The narrative structure of early story films was apparently enough to

knit the two types of cinematic practice into an aesthetic whole for

viewers of the time. Indeed there's a curious Edison film from

around 1904, not part of the regular Edison release schedule, which

shows a

group of people making its way by various means of transport from one

end of Manhattan Island to the other. There's no connecting narrative

— the shots just seem to be a series of “actualities” linked only by

the presence of the same characters in each sequence. It's been

suggested by film scholars that these sequences may have been shot as

“entr' acts” for a stage play, showing the play's characters moving

from location to location in the story — something to pass the time

and amuse an audience while the stagehands shifted sets behind the

projected images.

If in such a production you just replaced the scenes on the stage sets

with filmed interiors, shot head-on against painted theatrical

backdrops,

you'd have a pretty fair paradigm for an early narrative film.

Even imagining how such anomalous cinematic approaches could have been

reconciled for viewers within the same film, it's hard not to see the

results as crude. But such anomalous approaches have almost always

been a part of cinematic practice — and the momentum of narrative has

always been able to reconcile them.

Look at John Ford's Stagecoach

again and see how stunningly photographed images of real locations

alternate with studio work (above) in which sets and back-projections stand in

for exterior locales. It's objectively weird, aesthetically

inconsistent, but our eyes, accustomed

to back-projections in films of this era, don't read it as such.

The conventions are always shifting, of course. The studio-built

interior sets of Stagecoach (above) are fully three-dimensional and

convincing as actual locations — a far cry from Edison's patently

two-dimensional interior sets painted on flats. But Ford's

back-projection exteriors are convincing only to the degree that we

choose to be

convinced by them, as Edison's audiences chose to be convinced by his

artificial interior sets.

The history of the shift from “theatrical” to fully dimensional interiors in movies would be fascinating to chart.

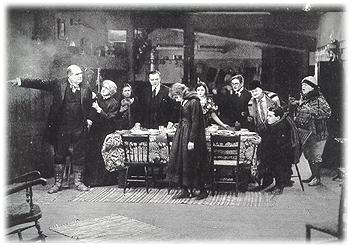

One of Griffith's main formal concerns in the Biograph years was

developing a way of staging and photographing interiors on sets in

spatially interesting ways, to create a stronger illusion of being in

real rooms — but he never totally abandoned proscenium framing.

Why?

I'm beginning to think that proscenium framing for interiors continued

to have a degree of glamor for filmmakers throughout the silent era, by

evoking the prestige of the stage.

Twice in Erotikon, from

1920 (above), which has elaborately constructed and

convincing interior sets, such a set is introduced by a wide, head-on

proscenium type shot — before Stiller moves in and starts shooting the

room as though it were a practical location, sometimes even shooting in

mirrors that reflect the wall behind the camera, utterly abolishing the

theatrical mode by showing us the “fourth wall”.

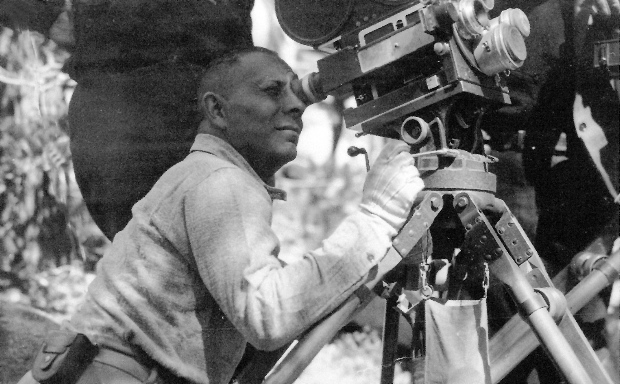

In Peter Pan, Herbert Brenon (above, with camerman James Wong Howe and Betty Bronson) does something similar with the opening sequence

in the nursery — which he starts out showing only from angles that

would have been available to members of an audience seated in front of

his set, but then proceeds to penetrate from angles only available to

performers inside the set.

Both Erotikon and Peter Pan were adaptations of popular stage

plays, and the filmmaker in each case may have wanted to remind viewers

of the film's prestigious theatrical provenance.

Von Stroheim seems to have been the first film artist to abolish the

theatrical mode for interiors as a matter of basic aesthetic principal,

and he was followed in this approach fairly consistently by Murnau as

well. From them derive the dynamic spatial interiors of Renoir

and Welles.

[With thanks to shahn of sixmatinis and the seventh art for a recent post which got me thinking about this subject again.]

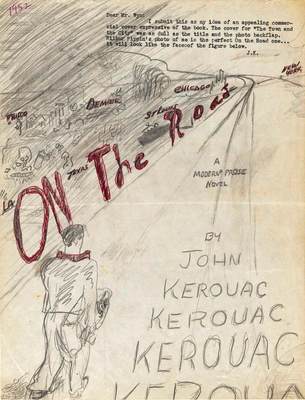

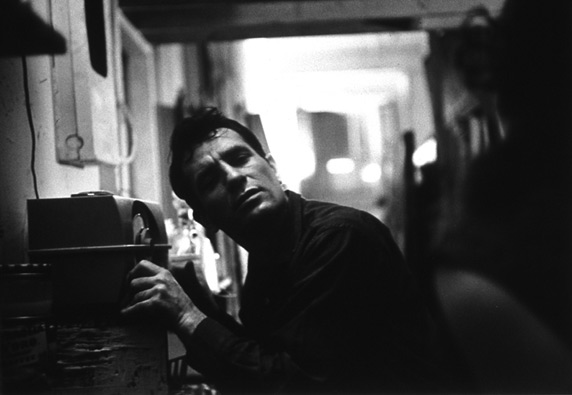

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of Jack Kerouac's On the Road

and the book is getting a lot of attention. (That's Kerouac's

design for the book's cover above.) It was certainly an important

book — crystalizing the odd malaise that gripped America after WWII

and presenting an image of the way American youth would react to it, in

increasing numbers, by cutting loose from everything, drifting into a

world of sensuality and drugs, hitting the road in search of . . .

something. The book's freewheeling, lyrical prose was brilliant

enough to allow one to take it seriously as a work of art, to place it

in the picaresque tradition of Huckleberry Finn.

The moral and spiritual emptiness of On the Road's

protagonists was part of the

book's truth, of course, but that truth, to me, was a thin one, without

any deep humane dimensions — and this is nowhere better revealed than

in

the book's depiction of women. It's not just that Kerouac's

protagonist's treat them badly, or indifferently, but that they don't

seem to see them as human beings — and, more importantly, that the

author himself doesn't seem to see them as human beings. This is

quite a different thing from writing women characters badly,

unconvincingly — quite a different thing from ignoring women or even

raging against them for their otherness, as Henry Miller sometimes

did.

Kerouac simply seems to see women as an existential nullity.

Some women say this doesn't bother them — that the freedom

and exhilaration of the book's spirit is an inspiration to them as

women, however the women in the book are drawn. I can appreciate

the sense of that — but it doesn't lessen my revulsion at the way the

women in the book are drawn. It strikes me as revealing a basic

truth about almost all beat fiction and poetry — that once you get

past the attitude, the style, there's very little underneath it, and

what there is underneath it is often repellent.

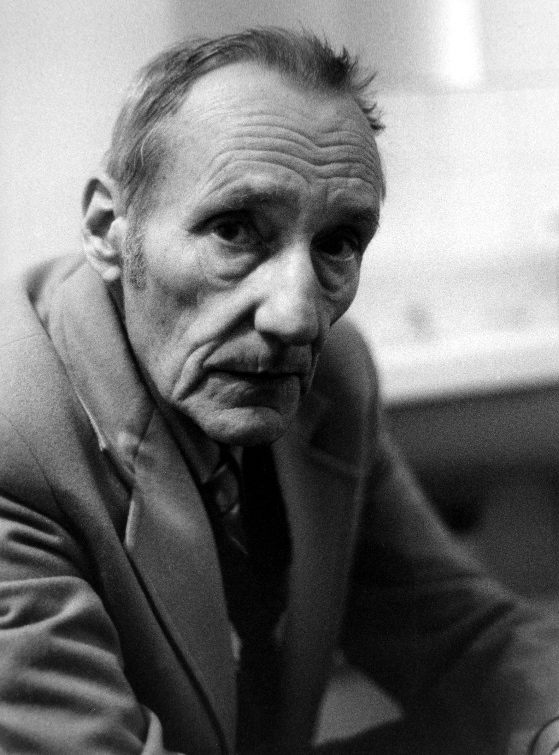

William Burrough's magical, fractured prose, best appreciated in his

recorded readings of it, is invigorating and exciting — but a little

of it goes a long way. It's like a jazz improvisation on a melody

that the musician has forgotten, or never knew in the first

place. It's a gesture, an exercise, not an artistic creation.

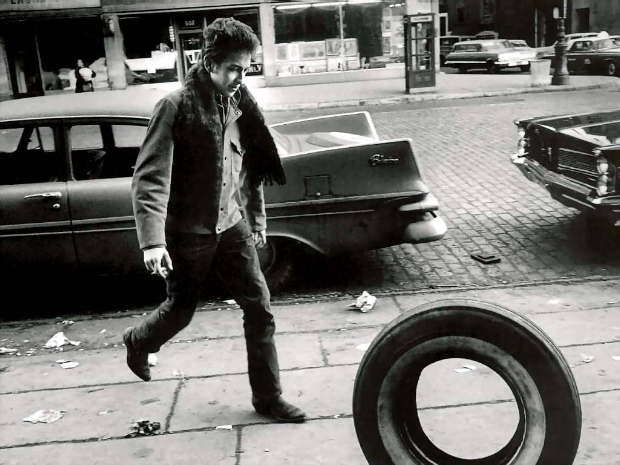

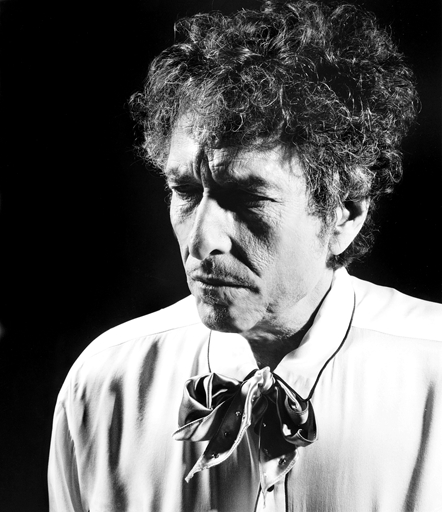

Bob Dylan was the great inheritor of the beat tradition, but he

grounded his improvisations firmly in the blues and folk traditions —

he was engaged, with a great deal of humility, in a conversation with something beyond himself.

His early work is marred by some of the same misogyny one finds in the

beats, by images of women that alternate between goddess and destroyer,

with no convincing human presence in either.

But Dylan, unlike the beats, grew as an artist. He listened to

the culture around him, its roots and moods, and talked back to

it. His work wasn't just an interior howl, a negation — he was a

rolling stone who could step outside of himself and watch himself roll.

When Kerouac tried that he was appalled by what he saw — or didn't

see. He ended his life drunk, stoned, in a state of utter decay and

despair. We can see the roots of that in On the Road. Kierkegaard said that the precise quality of despair is that it is unaware of itself. On the Road

is a harrowing portrait of a despair that is unaware of itself — one

its author shared, unawares, with the book's protagonists.

Kerouac's defenders say that only the work matters — not the

life. But I say that with Kerouac the life is in the work — is

not

transcended in the work. Which is not to say that the book isn't an

extraordinary thing, with passages of true greatness, depictions of

places and moods that are indelible, an authentic and often moving

voice with it's its own kind of feckless grandeur. It's just to say that there's something missing from it —

some element of heart and soul and sympathy that is crucial to any great work of art.

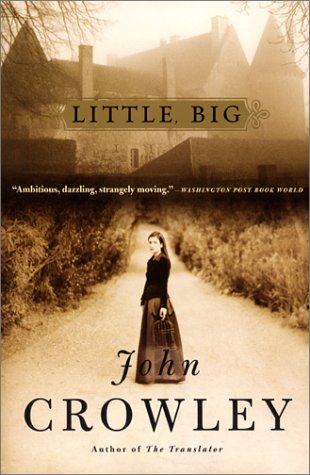

In his fascinating novel Little, Big, John Crowley proposes the idea that time does not actually elapse between

Christmases — that at Christmas we simply flip into another time frame

in which it is always Christmas and always will be. Then we flip

out of it again.

This is certainly how Christmas feels, and it ties in with some ideas Octavio Paz proposes in The Labyrinth Of Solitude, his great meditation on Mexican history and the Mexican character.

In the book, Paz discusses the importance of the fiesta

in Mexican life, as a time when Mexicans cast off their masks, the

barriers they erect against any penetration of their characteristic

solitude, and feel free to commune with others, sometimes socially,

sometimes erotically, sometimes violently.

Paz suggests that fiestas, and

all ritual celebrations, don't commemorate an event but recreate it —

recreate a transcendent moment when time is dissolved and masks are

discarded. This of course ties in with the theological

proposition that Jesus is actually present in the wine and the host at

Christian communion services — and more broadly with Kierkegaard's notion that

Christian believers are literally contemporaries of Christ.

And of course it explains why time does not pass between Christmases.

The cuba libre,

rum and Coke, always seemed like a pop cocktail to me. I guess I

associated it with early drinking in college, when it was the only

mixed drink anyone knew how to make and seemed like a painless way

to ingest a lot of alcohol.

But that was before I tried Ernest Hemingway's recipe for a cuba libre,

which is something else again. The key to this recipe is getting

hold of a Mexican Coke, which is still made with sugar, as it was in

Hemingway's day. You want to taste the rum and its parent

cane sugar all at once. (If you can't find Mexican Coke, forget I ever mentioned the cuba libre — corn syrup has no place in it.)

Squeeze half a lime into a cocktail glass. Pour in a jigger of

Bacardi white rum, add the remains of the squeezed lime and plenty of

ice and pour the Coke over it.

The result is not too sweet and not too sour and it has an exhilarating

freshness. After a couple of these you'll be imagining

you're on a tropical beach somewhere . . . and after a few more you'll

be

convinced you really are on a tropical beach somewhere.

At that point, just relax and listen to the sounds of the surf and the wind rustling the palm fronds.

Above

are the fish we took away from our fishing expedition on the Mar de

Cortés — all good for eating. We ate some of the catch in La Paz before

we left, the rest made it, frozen, to Las Vegas and Los Angeles, where

it served for a couple more wonderful meals.

We caught other fish on our expedition — including a few bonito, all

but one of which was thrown back. The biggest of them was saved to

serve as shark bait for a friend of our captain. We caught

several needlefish — nasty looking things with long pointed snouts

which are no good for eating. “Banditos” our captain called them,

disdainfully, because they steal bait. If one got hooked, the

captain had to beat it senseless with a wooden club before he removed the hook, to avoid

having his hands lacerated by the needlefish's sharp teeth.

Nora watched this procedure with burning eyes. “I almost can't

stand to look,” she said. “But it's also kind of exciting.” This struck me as a very Spanish response, with the

appeal of the bullfight in it.

In any fishing tale there's always the part about the one that got away.

Just before we headed back to shore, with our bait almost used up, I

hooked a huge fish. It felt like the big bonito I'd caught

earlier — maybe heavier. It kept wanting to sound and came up

slowly, when I could move it towards the boat, like a massive lead weight at the end of the line. When I got it to

within four or five feet of the surface we could see, in the dappled sunlight rippling through the water, that it was a gigantic

yellowfin tuna. The captain was very excited — this was

a stupendous fish. I was too excited. I jerked the line a

little too hard and the hook slipped out and I watched the amazing

thing swim away again into the depths. I was sad but also oddly

moved by the encounter.

Below, pelicans feed on the remains of our fish, after the captain had filleted them:

After I dropped our catch off at the restaurant at the Los Arcos I went

up to the bar for a beer. I was exhausted from the long drive to

and from the beach and the hours out on the water, all on far too

little sleep. But my nerves were singing. I knew I had

experienced something extraordinary. There was no way I could go

to sleep.

That's the moment I come back to when I think about Baja California —

the way the cold beer tasted, and the image that kept going through my

mind of the big tuna swimming away into the Mar de Cortés, its

silver sides and yellow fins flashing a few times before it disappeared

into the deep blue.

Part of my heart went with it, and is still there — lost at sea.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

The horror! The horror!

I recently came upon a term, “risk homeostasis”, which I think helps explain why driving in Mexico feels safer, and may in fact be safer, than driving in the U. S.

Roads and streets in Mexico tend not to be as well-maintained as they are in the States, lanes tend not to be as well marked (or respected when they are marked), traffic signs are treated very casually — in La Paz, many stop signs are completely obscured by foliage. (You quickly learn to come to a full stop at every bushy tree near the corner of an intersection.)

The result is that Mexicans are forced to drive with greater care, greater attention to the behavior and greater respect for the prerogatives of other drivers — not to mention pedestrians . . . and goats.

In the States, where road and street surfaces tend to be impeccable, lanes are clearly marked, traffic signs prominent and logically placed, livestock properly penned, people rely on these things to allow them to drive more carelessly — while talking on a cell phone, for example, with very little attention given to immediate traffic conditions around the vehicle. They assume that the markings and the rules will keep them out of accidents — but based on that assumption they feel free to expose themselves more to the hazards of unpredictable incidents.

This is “risk homeostasis”, a phenomenon observed in all security systems — people “consume” improvements in security and use them to justify taking more risks.

The result can be paradoxical. Here in the U. S., more pedestrians are killed in clearly marked crosswalks than in unmarked crosswalks — the bright white solid lines give them a false sense of security and lessen their attention to the actual behavior of drivers. (The GPS system in my car, above, has no detailed map data for Mexico — it only told me roughly where I was on the Baja California peninsula . . . all the rest I had to figure out for myself.)

My sister was terrified by the idea of driving in Mexico — because it all looked so anarchic. But it wasn’t anarchic at all — just the opposite. Almost all drivers were following one basic rule, which transcended all the other less basic rules — pay close attention to what your fellow drivers are doing and don’t run into them.

It’s the one basic rule that no improvements in traffic systems can

promote, and that many improvements in traffic systems can actually

undermine. It’s against the law in Mexico to drive while talking on a

cell phone — but it’s something you wouldn’t be likely to do anyway.

You wouldn’t feel safe. You may feel safe driving while talking on a

cell phone in the U. S., but you very likely aren’t.

By directing so much of your attention away from the traffic around

you, you have essentially “consumed” the advantages the U. S. road

system has over the Mexican road system.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

When

we think of dreamlike films, or dream sequences within films, we

inevitably think of the expressionistic style filmmakers often use

to signal a dream state — but of course real dreams do not present

themselves in that way. We might, in a dream, find ourselves at home

and discover a previously unnoticed door opening onto a previously

unsuspected wing of the house — but that wing is not appointed like

the cabinet of Dr. Caligari . . . it is as convincingly real a place,

in the dream, as the actual house we know.

One

of the sweetest aspects of traveling in Mexico is experiencing a

society that has not been thoroughly corporatized. Big U. S.

corporations have infected Mexico on a large scale, but you only see

the manifestation of this in localized areas of big cities — the strip

developments on the outskirts of towns where Wal-Mart and Office Depot

rule. There's a Burger King and an Applebee's on the malecón in La Paz, but they still seem anomalous, like unsightly trash dumps in a vacant lot.

Everywhere else, businesses seem to be run by, stamped

with the personality of, actual human beings. Restaurants and taco stands

are decorated according to the eccentric tastes of the

proprietors. You visit them not to find some standardized form of

service and decor, originating in some distant corporate headquarters,

but to have the adventure of meeting and interacting with the individuals who have personally organized these enterprises.

Las Vegas knows the advantage of this sort of eccentricity —

restaurants here, like casinos, have quirky themes, promise to be

“experiences” . . . but it's all professionally designed, the product

of artful concepts rather than of individual obsessions or

passions. It's better than nothing but it's a far cry from the

organic expressiveness of everyday Mexican culture.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

While the ultimate virtue in Wilde’s essays is in make-believe, the

denouement of his dramas and narratives is that masks have to go.

We must acknowledge what we are. Wilde at least was keen to do

so. Though he offered himself as the apostle of pleasure, his

created world contains much pain. In the smashup of his fortunes

rather than in their apogee his cast of mind fully appeared . . .

Essentially Wilde was conducting, in the most

civilized way, an anatomy of his society, and a radical reconsideration

of its ethics. He knew all the secrets and could expose all the

pretense. Along with Blake and Nietzsche he was proposing that

good and evil are not what they seem, that moral tabs cannot cope with

the complexity of behavior. His greatness as a writer is partly

the result of the enlargement of sympathy which he demanded for

society’s victims . . .

As for his wit, its balance was more hazardously maintained than is

realized. Although it lays claim to arrogance, it seeks to please

us. Of all writers, Wilde was perhaps the best company.

Always endangered, he laughs at his plight, and on his way to the loss

of everything he jollies society for being so much harsher than he is,

so much less graceful, so much less attractive. And once we

recognize that his charm is threatened, its eye on the door left open

for the witless law, it becomes even more beguiling . . .

He occupied, as he insisted, a “symbolical relation” to his time.

He ranged over the visible and invisible worlds, and dominated them by

his unusual views. He is not one of those writers who as the

centuries change lose their relevance. Wilde is one of us.

His wit is an agent of renewal, as pertinent now as a hundred years

ago. The questions posed by both his art and his life lend his

art a quality of earnestness, an earnestness which he always disavowed.

— Richard

Ellman

from his

biography Oscar Wilde

In Mexico, when

referring to the U. S. State of California, don't call it California,

call it Alta California, thus showing that you realize there are three

Californias — the U. S. state and the two Mexican states, Baja

California and Baja California Sur. Mexicans are so unaccustomed

to gringos using the term Alta California that they will sometime laugh

when they hear it, but it's a laugh of satisfaction and approval.

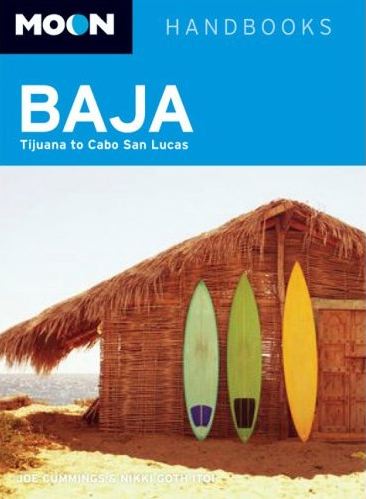

I'm sure I don't have to encourage anyone not to refer to Cabo San Lucas as “Cabo”, but by the same token, don't refer to Baja California as Baja. Baja

just means “lower”. It's sort of like saying, “I'm going to

North,” when what you mean is, “I'm going to North Dakota.”

In spite of the above, get hold of a copy Baja in the Moon Handbooks series. It offered the most sensible advice about traveling in Baja California and the most reliable

recommendations about hotels and restaurants. We carried the

2004 edition, which was already outdated in some respects, but there's

a new edition coming out this month (see above.) Also, be sure to

carry the AAA road map of Baja California, the best one available north

of the line.

Take along some chewable Pepto Bismol tablets. These handled all

the (very mild) stomach upsets we suffered in Mexico. Take along

some Benadryl, in case of wasp and bee stings. In the desert

environment of Baja California, bees and wasps will appear out of

nowhere, in the midst of the most barren wasteland, if you expose so

much as cookie crumb, or open a container of anything liquid. If

you keep items made with sugar wrapped and stuff tissue paper into the

tops of open soda or beer containers, they vanish just as quickly.

But accidents can happen. On our fishing expedition, a fellow

passenger in our van popped open a beer when she got back to the beach

after her time on the water. Within about two sips, and without

her realizing it, a bee got into the bottle. She swallowed it and

it stung the inside of her throat on the way down. We were at

least an hour away from any kind of medical facility, and if my sister

hadn't had some liquid Benadryl in her fanny pack, the situation could

have been dangerous. As it was the Benadryl reduced the swelling

in the woman's throat, allowing her to breathe freely, and some Advil

(which my sister was also carrying) helped her manage the excruciating

pain

I have no idea why my sister was carrying Benadryl in her fanny pack —

just as a general precaution, she claimed, though I suspect that

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe put the idea into her head precisely for

the emergency in question.

This brings me to my final tip — always listen to the promptings of La Morenita. She will never steer you wrong.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

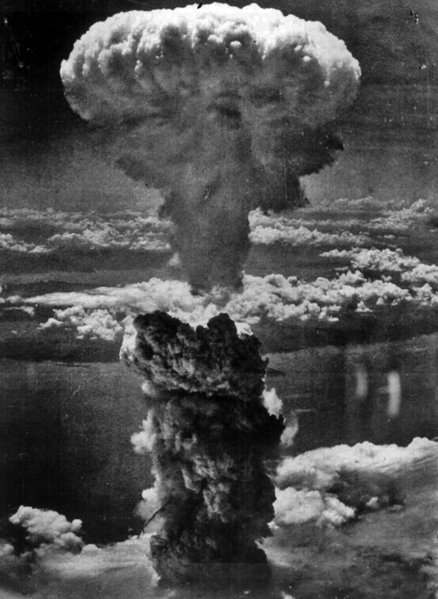

World War Two was a “good war”. America and its allies pulled together

and destroyed the Axis powers. On balance, and in retrospect, it

has to be considered one of the great achievements of

humane civilization. But human beings don’t live on balance or in

retrospect, particularly where war is concerned. They live inside

the horror of it and it takes a toll on individuals and on societies

which can never be fully measured.

The upbeat spirit of American propaganda during the war, and the

genuine satisfactions of victory, veiled the true experience of the war

for millions — not just for those who fought it on the battlefields of the

world, but for those at home who lived in terror that their loved ones at

the front might never return . . . and of course, most especially, for those at home whose loved ones didn’t return. On a broader level, anyone who simply witnessed

the spectacle of total war on a global scale, from whatever distance, had

to have experienced a soul-shaking anxiety about the fragility of all

social structures and cultural norms.

After WWII, the whole planet experienced post-traumatic stress disorder

— localized in this case by the fact of the atomic bomb, which ended

the war but left the world with a paradox that wouldn’t go away.

It took an act of colossal horror to finally “win” this good

war. And the prospect of this horror being again visited on the

world was far from unimaginable.

We now know a lot more than we used to about post-traumatic stress

disorder and the ways it can be treated. In the immediate post-war era, the

phenomenon was more elusive, and often unrecognized. We made

meaningful social restitution to the veterans of the war, with measures like

the G. I. Bill — we reconstructed the devastated nations we

conquered. But that just scratched the surface.

It was in art that the true psychic cost of the war was exposed and explored — nowhere more pointedly than in film noir. The sort of trauma that engenders PTSD is identifiable by several characteristics — a sense of being out of control and confused, a

sense of terror, a sense of being outside the normal realm of human

experience. Is there a better description of the usual

predicament of the protagonist in a classic film noir?

PTSD on a broad cultural and societal level is what best explains the phenomenon of film noir, which on its surface is so mysterious. Why should a triumphant

nation, after a great collective victory in a good war, have been

gripped by that mood of existential dread which informs so many Hollywood films of the post-war era? Why should the most spectacular achievement of American arms have led

to a crisis of manhood, a sense of impotence, a fear of powerful women

incarnated in the morbid fantasy of the femme fatale?

Film noir was a dream landscape where the buried costs of WWII could be recognized, reckoned and mourned, as a prelude to psychic recovery, or at least psychic survival.

Veterans of combat often report the difficulty of dealing with people

who have not shared their experience of it — people who can never

really know what it’s like. Film noir, far more than the WWII combat film, was one of the few arenas of American life where the true legacies of war, its lingering moral and

psychological dislocations, could be engaged without apology or shame.

First

tip — if you’re a guy, wear a straw cowboy hat. I don’t pretend

to understand the full cultural significance of the straw cowboy hat in

Mexico, but I do know that it has replaced the sombrero as the national

headgear, though it’s not nearly as ubiquitous as the sombrero used to

be. The sombrero has become ceremonial, part of a costume used on

festive occasions and by theatrical mariachi troupes. The bands

of strolling musicians who play in restaurants, for example, wear straw

cowboy hats.

Hip young kids in Mexico don’t wear straw cowboy hats, nor do

sophisticated professionals, and the baseball cap is making strong

inroads everywhere, even in rural areas.

The straw cowboy hat

seems to have something of the significance of the cowboy hat in

America, a sign of solidarity with the nation’s rural roots and the

romance of the ranchero.

The important thing is that Yankee tourists don’t usually wear straw

cowboy hats. My three traveling companions, all blond, were

usually taken at once as Yankees, but people sometimes expressed

surprise to find that I wasn’t Mexican. Even when I was taken as

a gringo, the hat seemed to confer on me the benefit of the doubt,

especially at the ubiquitous army checkpoints where they stop your car

to look for drugs. (They have stepped these up recently at the

urging of the U. S. government, so don’t blame Mexico for the resulting

inconvenience.) We were usually ushered through these with

only the most cursory of inspections, while other gringos were being

searched rigorously. I attribute this to the formal and

respectful greetings I offered to the soldiers — and to the hat.

I live in a U. S. state that still considers itself Western.

Wearing a cowboy hat in Las Vegas doesn’t arouse any special curiosity

outside of the fancy casinos or yuppie enclaves like Summerlin . . . so

I didn’t feel that wearing one in Mexico constituted any kind of

charade. The hat seems to mean more or less the same thing on

both sides of the border. Maybe that’s the point.

Second tip — travel with kids. Mexicans have an instinctive

reaction to kids that instantly dissolves all linguistic and

cultural barriers. They like having them around. They like

you for bringing them around.

Third tip — avoid the Pacific coast of Baja California above

Ensenada. Even if you’re motoring down from San Diego, go east

and cross at Tecate. The Pacific coast above Ensenada offers a

vision of the future of Baja California, as more and more Yankees

retire or build vacation homes there. The vision will make you

ashamed of being a Yankee and depressed about the future of Baja

California.

Fourth tip — go! Just go. Below Ensenada, and outside the

city limits of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico is still there. Its

gracious and humane culture has much to teach and many ways of

enchanting its complacent neighbors north of the border.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]