On

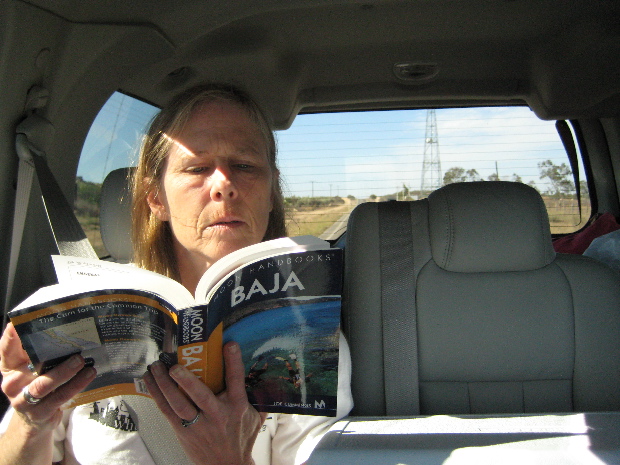

the first day of our drive to Baja California we got off to a late

start — a miscalculation that led to us having to spend our first

night in Blythe, in Alta California. I'm not sure what the deal

with Blythe is, but it seemed like a depressed and hopeless sort of

place. We stayed in a lousy, overpriced motel and were happy to

be on our way again in the morning. Above is a picture of a

rooster on top of a cafe in Vidal Junction, Alta California, on the

road to Blythe. The cafe was closed and the only restrooms we

could find in Vidal Junction were some dirty Porta-Potties behind a gas

station, which was also closed. The sight of a new moon behind the rooster cheered us up immeasurably.

If you drop more or less straight down from Las Vegas you hit the

Mexican border at

Mexicali, but we'd been told that crossing at the smaller town of

Tecate was quicker and

easier, so we veered off westward at El Centro on the I-8, then dropped

down to a smaller road that skirts the border on its way to

Tecate. (Tecate is where the great Mexican beer of the same name

originated, though it's now brewed in other places in Mexico as well.)

It was fascinating to drive through the Imperial Valley of Alta California, past the huge

Sahara-like sandscape of Imperial Dunes and through the lush cultivated

fields beyond them. The water that irrigates the Imperial Valley,

and makes it one of the most productive agricultural regions in the

world, comes from the Colorado River, which used to empty into the top

of the Mar de Cortés. Now only a trickle of it arrives at the

apex of the great sea and the rich delta that used to be there is more

or less a wasteland.

The land above the border on the road to Tecate is well-watered, too,

and very beautiful. We passed four U. S. Border Patrol cars along

the road before crossing quickly and easily into Mexico at

Tecate. You need a Mexican tourist visa if you plan to travel

south of the “tourist zone”, or more than about 20 miles into

Mexico. Lee had gotten hers and her kids' in Los Angeles but the

Mexican consulate in Las Vegas doesn't issue them. I got one on

the Mexican side of the border in about 20 minutes, with no trouble at

all. The Mexican border officials were friendly and efficient.

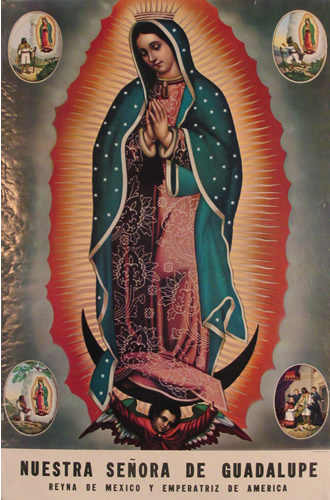

Somehow we managed to find our way through the teeming streets of

Tecate onto Mexico 3, which cuts across the top of Baja California and

hits Mexico 1, and the Pacific, at Ensenada. The road passes

through high valleys where grapes are cultivated and wine made. We

stopped at the largest of the Baja California wineries, L. A. Cetto, a

lovely establishment surrounded by a sea of green vines.

Lee and

I sampled and bought some good, cheap wines there . . .

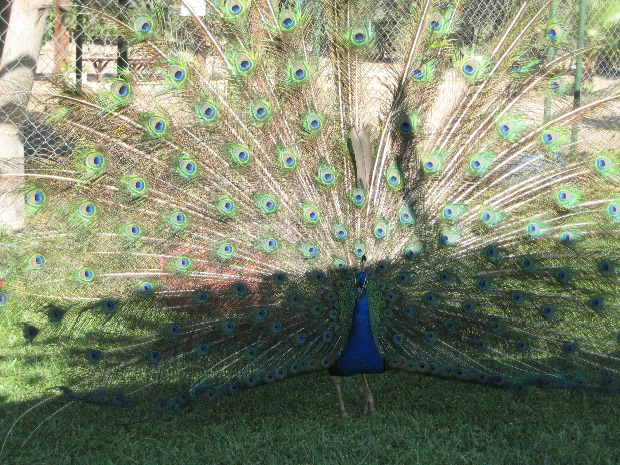

The kids were

diverted by a pen that held burros . . .

. . . and peacocks . . .

At Ensenada we headed straight for the city's fish market, with its

extraordinary displays of seafood arranged in elaborate, artful piles. We

had some indifferent seafood tacos at one of the small stalls lining

one side of the market, then cast about for a place to stay for the

night.

We lucked into El Rey Sol, a pleasant motel-like place with a protected

parking lot, a great little bar and a good pool for the kids.

While the kids swam, Lee and I washed away the dust of the road with

beers and margaritas, talking to a cheerful bartender who recommended

good seafood stands in Baja California Sur, and to other travelers,

including a surfer who'd explored the undiscovered breaks of the

peninsula in his youth and was now revisiting the region with his young

family.

After the motel disaster in Blythe, Lee and I had discussed the

dehumanization of roadside inns in America, contrasting them with the

rich inn culture of Dickens' time, when inns always offered inviting

public rooms where travelers could meet and exchange tales of the

road. All the Mexican hotels and motels we stayed at had such

public rooms, and they were always in use — just one of the many areas

in which Mexican culture reveals its humane genius and outshines its

“richer” neighbor to the north.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]