The environmental, or broad cultural racism in the first half of The

Birth Of A Nation finds expression in two ways. The first is the

general depiction of blacks under slavery as well-treated and happy.

It can be argued that some blacks under slavery were well-treated,

insofar as anyone held in involuntary servitude can be said to be

well-treated, and that some blacks under slavery were happy, insofar

as anyone held in involuntary servitude can be said to be happy. But

presenting such blacks as the only representatives of slavery in a film

with the epic scope of The

Birth Of A Nation cannot be seen as merely

an act of dramatic selection. All the characters in the film are

emblematic of broader social realities, and the view of slavery

presented here, as part of the “gracious” Southern social order that

will be swept away by the Civil War, has an ideological dimension —

and

the ideology is based on a lie. Whether or not slavery was a

“necessary evil” or a crime against humanity or on balance a benign

institution, it did not even remotely resemble the portrait of it

offered up in The

Birth Of A Nation.

The second expression of environmental racism is more complex. It lies

in Griffith's decision to have all blacks who are presented as

individuals in the film played by whites in blackface. In this he was

following

conventional theatrical practice. We know, from his testimony in a

censorship hearing for the film, that he considered the issue before

deciding on the blackface solution, but he probably wouldn't have been

terribly self-conscious about it, so common was the practice. But its

very commonness raises interesting issues.

On one level, the blackface caricature of an African-American by a

white actor carries its own critique within it. There is no theatrical

deception involved — the glaringly obvious make-up reveals that the

convention is a convention, and one of the things expressed in the

convention is that whites have appropriated the image of the black,

that whites will control the image of the black. The image must be,

therefore, on the blackened face of it, constructed. The convention

announces that whites feel empowered to construct, to control, the

image of the black, but also admits that the image is inauthentic. It

leaves open the possibility that blacks might construct other images of

themselves, if they had the power to do so — and that they might not

participate willingly in these particular constructions of their

images. There are more questioned raised than answered by the

convention of blackface, at least on an unconscious level.

The pathological, psycho-sexual racism of The

Birth Of A Nation

doesn't emerge until about 16 minutes into the film, with the first

appearance of Austin Stoneman's sluttish maid. Previously, Stoneman

has been

established as a grotesque figure, with a club foot and an ill-fitting

wig. Suspicions about him have been aroused by revealing that he

spends a lot of time in his library, where his family never visits.

He's never shown in his own home — his sons even march off to war from

that home when he is not present. This is Victorian code for the fact

that Stoneman is a creep — at the very least a deeply problematic

figure. Devotion to the

home was an essential element of male rectitude in Victorian fiction.

With the appearance of Stoneman's maid we learn the dark secret he is

hiding — an illicit sexual relationship with his maid, a mulatto

woman. Stoneman is a thinly-veiled stand-in for the great anti-slavery

statesman Thaddeus Stevens. Stevens' radical views on Reconstruction

can be, and have been, criticized as over-zealous and impractical, but

Griffith is suggesting that his polity was the direct result of sexual

perversion, the impulse towards unbridled sexual lust in general and

miscegenation in particular. The mere fact that his slovenly maid is a

mulatto, the product of miscegenation, sets up the association of black

enfranchisement, even black aspirations towards dignity, with an

undiscriminating, animalistic sexuality. The maid is offended when a

visitor to Stevens'

library treats her dismissively, as a mere servant — after he leaves

she flings herself to the floor and writhes in anguish, her shoulders

immodestly bared, her hands playing over her breasts. Her behavior is

not just indecorous — it's positively bestial.

There is no evidence that Thaddeus Stevens ever had an affair with a

mulatto maid, or that he engaged in sexual misconduct of any kind.

What we

have here is pure, and very bizarre, fantasy, which can only be

explained by the pathological association of black enfranchisement and

equality with the destructive unleashing of the libido. A title card

announces that we have witnessed in the scenes described above “the

weakness” — Stoneman's lust for

a black woman — “that blighted a nation”. The entire Civil War and

the complex moral and economic forces that led to it, the entire

abolitionist cause, is reduced to sexual “perversion” in the form of

miscegenation.

Meanwhile, down South, the Civil War has broken out and almost

immediately the Cameron home is threatened by Negroes gone wild.

“Renegade” black soldiers, in Union uniforms, attack the town where the

Camerons live, and the Cameron home itself. Griffith concentrates

dramatically on the threat to the two Cameron sisters, hiding out in

their basement. Any viewer of the time would have recognized the

sexual component of the threat. The girls are clearly in danger of

being raped by the maniacs assaulting their home.

There were, in fact, no bands of renegade black soldiers running wild

in

the South. A title tells us, misleadingly, that the first black troops

were enlisted in South Carolina, which is true — but none of them

ever behaved the way these blacks troops do, which is what the title

implies. A title also tells us that the blacks have been incited to

their behavior by an irresponsible white commander. Griffith often

uses this device in the film to show he's not blaming blacks for their

behavior — only the white trash who spur them on. But this muddles

what's really being said between the lines. The bad whites in these

cases have failed to

exercise proper patrician supervision of and control over their black

charges, they have misdirected and unleashed the animalistic tendencies

of the blacks. The important point being driven home — and it's

driven home throughout the film — is that this potential for

animalistic behavior by blacks is always there and always needs to be

controlled. This is the white man's burden — his first duty in

protecting the home and its women.

A detachment of white Confederate soldiers rescues the Cameron girls

and their home — white actors in blackface help put out the fire in

the house and embrace these soldiers in gratitude. But in the course

of the film, the white deliverers

won't always get there on time . . . indeed, their failure to do so

on one crucial occasion will lead directly to the dramatic climax of

the film.

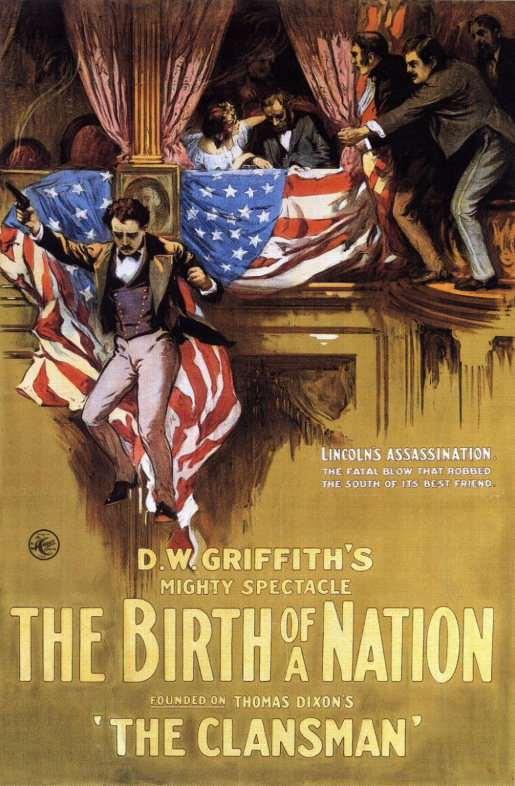

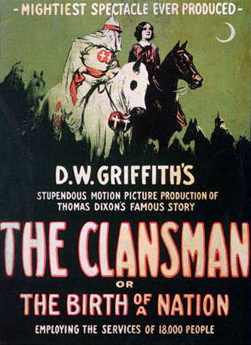

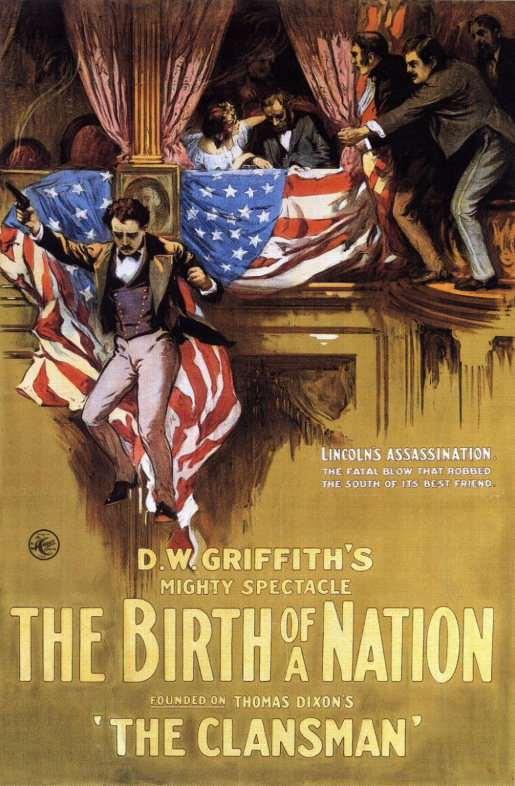

The first half of The

Birth Of A Nation ends with the assassination

of Lincoln, dramatically and quite accurately recreated onscreen. This

assassination has become a tragic, iconic component of America's

national myth, and in the film it is greeted by sorrow on both sides of

the Mason-Dixon line — with one exception. Stoneman's mistress exults

as she strokes Stoneman's arm lasciviously and tells him he's now the

most powerful man in the country. Her villainy and inhumanity could

not be

asserted more forcefully — a more direct connection could not be drawn

between the “history” we're about to watch unfold and the sexual

“perversion” of miscegenation. To this woman, and perhaps to Stoneman,

Lincoln's death only removes the greatest obstacle to the sexual union

of the black and white races.

It's really impossible to fully appreciate Griffith's artistry in this

film without recognizing how skillfully he inflects his national epic

with psycho-sexual themes, appealing to patriotism, nostalgia for a

more gracious age, reverence for the home, in order to set all these

things against the perceived horror of the pollution of the Aryan race

by admixture with inferior blood.

The environmental racism of The

Birth Of A Nation is not egregious by

the standards of its day. It wouldn't even have been egregious by the

standards of 1939, the year of Gone With the Wind, which simply used

cleverer and more sophisticated means to distract us from thinking too

seriously about the horrors and the enduring moral stain of slavery.

And in the first half of The

Birth Of A Nation, the more disturbing

and

pathological racist element is almost overwhelmed by the lyric beauty

of the film in its celebration of family and home and gallantry and

innocent courtly love.

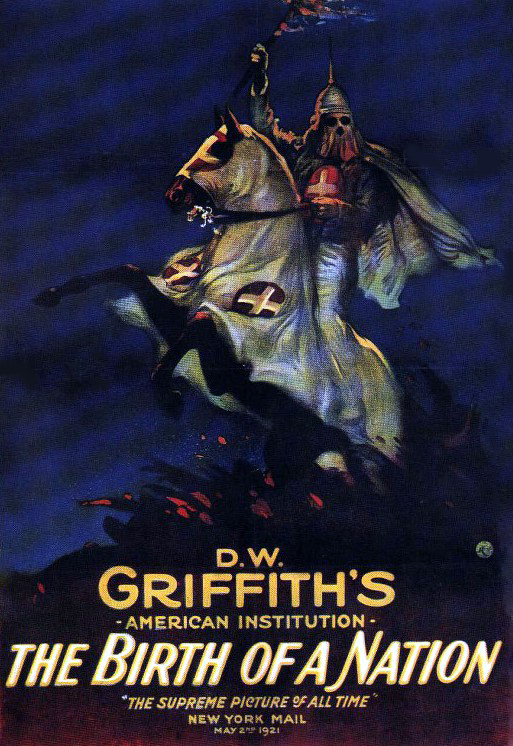

But we will see that the pathological element has been carefully

interwoven into the fabric of the film's first half precisely in order

to set up its emotional ascendancy in the second half — and there is

no question that this strategy was deliberate. The

Birth Of A Nation

prides itself on historical accuracy — with some justification. The

film is historically responsible and convincing in visual terms, and in

many of its recreations of actual events. The only times it departs

conspicuously from historical accuracy, the only times it unashamedly

distorts and

falsifies the historical record, are in those passages where it seeks

to promote its psycho-sexual racist agenda. That agenda will come to

dominate the second half of the film, but it was painstakingly and

strikingly foreshadowed in the first half.