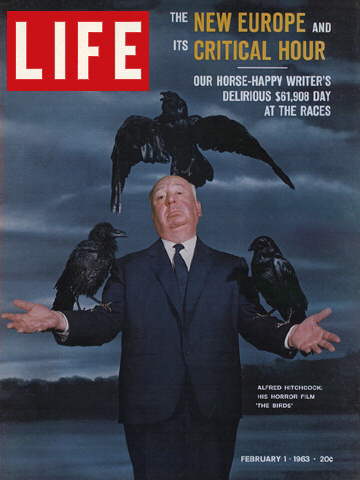

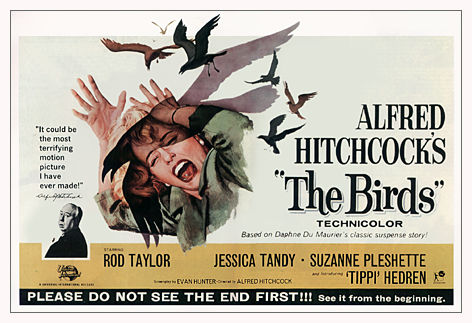

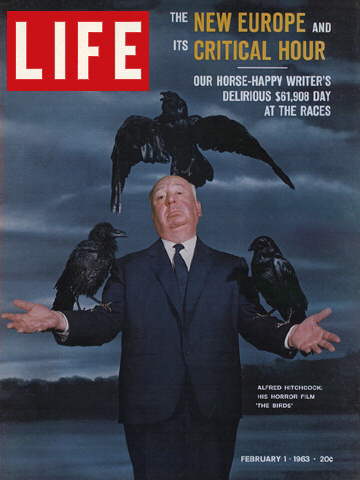

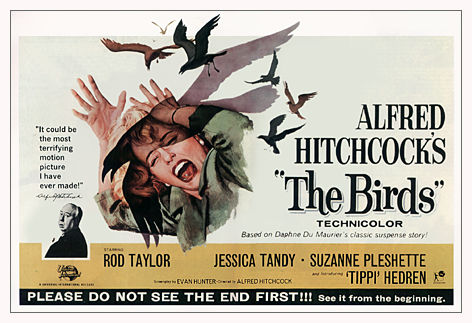

Robin Wood’s thoughtful and penetrating analysis of The Birds in Hitchcock’s Films Revisited is ultimately

disappointing

to me, because I don’t think Wood gets at the thematic heart of the

film, although he does acutely perceive its nature, it’s basic aesthetic

strategy, which is one it shares with all of Hitchcock’s great films —

and I think The Birds is one of Hitchcock’s great films.

The characteristic strategy of The Birds is to lure

the viewer into largely unconscious emotional reactions to images and

situations and then to shift the perceptual ground slightly (or

shockingly, as the case may be) in such a way that the viewer is

compelled to become conflicted about those reactions, consciously or

not.

The goal with Hitchcock is always to heighten moral

and/or spiritual awareness but his methods never involve pronouncements

of any kind, and thus rarely involve symbols than can be reduced to a

precise intellectual meaning. He is only interested in the psychic

currents

which he can tap, appeal to and uncover within the experience of the

viewer as he or she watches the film.

All great artists work this way of course, but if you

think that Hitchcock is just an entertainer, a supplier of sensation

for its own sake, a clever if eccentric practitioner of genre, you will

miss (at least on a conscious level) the full depth of his art.

So when Wood says that the birds in The Birds don’t

symbolize anything specific he is quite correct. But what the birds

do, and when they do it — their function as psychic agents in a

narrative about characters we are alternately drawn to and suspicious

of

— are crucial issues.

The film opens with a man in a pet shop trying,

unsuccessfully, to buy a pair of lovebirds as a gift for his young

sister. In the shop he meets a woman who’s attracted to him, later

buys the pair of lovebirds and drives them up to the remote fishing

village where the man’s sister lives, and leaves them for her. The

film ends with the young sister carrying the birds on an escape through

an apocalyptic landscape — devastated by a lethal revolt . . . of

birds.

What’s going on here? The lovebirds are not symbolic

per se in the artistic scheme of the film — they’re an image that

means different things to different characters at different stages of

the narrative. What’s crucial, it seems to me, is that the lovebirds

are a couple and that they live in a cage. They incarnate a paradox —

are they trapped, or are

they safe? They’re both, obviously — but which condition is most

important? That’s the question the film poses, and answers, after a

fashion.

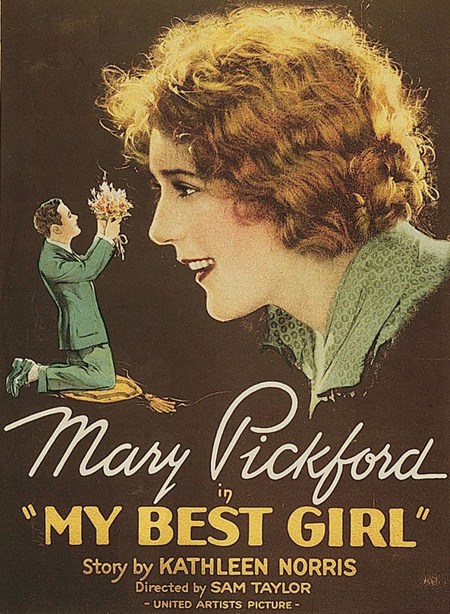

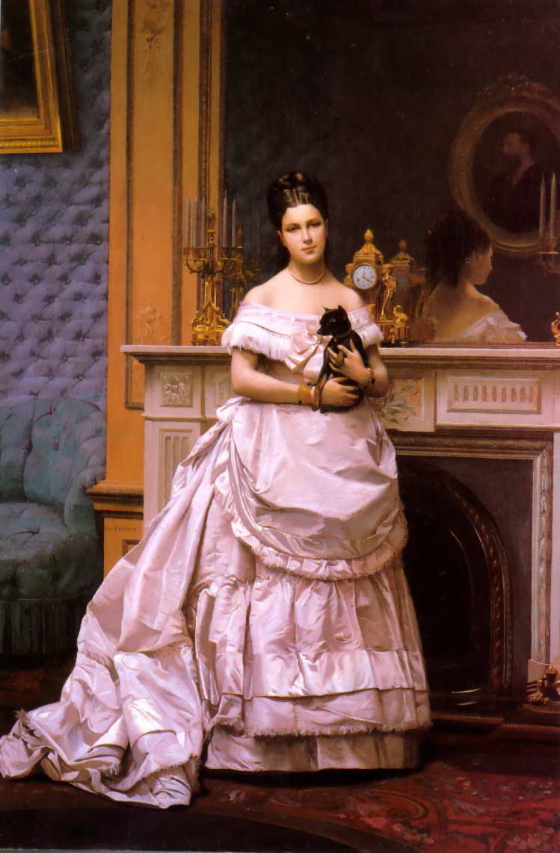

The woman in the pet shop is an irresponsible heiress

— a bird in a gilded cage, as Wood observes, but alone. When she runs into a man who

wants lovebirds in a cage, she develops what seems to be an irrational

attraction to him. The imagery is very ambiguous here, but suggestive. Is she looking

for company in her cage, a man who’ll share her prison with her?

It turns out that the man is the son of a woman who

lost her husband, his father, and is thoroughly traumatized by the

loss. She clings to her son, interferes with his desire to find a

partner of his own — places an intolerable burden on him to become the

head of the family, father to his sister. The mother’s grasping is not

Oedipal, exactly — it’s more a terror of being alone, of being

incomplete. The family’s loss of its father/husband has created a

vacuum in which neurosis breeds.

So the lovebirds, to the man, are an image of the

wholeness he can’t supply — a magical substitution which might allow

him to seek his own wholeness in a new relationship.

The lovebirds may not mean exactly the same thing to

the man and the woman in the pet shop but they crystallize each

other’s

deepest needs and desires. How could they not fall in love in the

presence of such an image?

But the image won’t stay put — won’t stabilize itself

for either of them. Other birds, uncaged birds, gather above them

menacingly. The man catches the woman delivering the lovebirds to his

sister, is

touched, intrigued, drawn to her, as she obviously is to him. At that

moment a seagull attacks the woman, for no apparent reason.

Later, the woman reveals to the man that her mother

deserted her when she was child. At that moment a flock of birds

suddenly attacks the children at the sister’s birthday party. It’s as

though the creatures have emerged demonically from the woman’s ravaged

psyche.

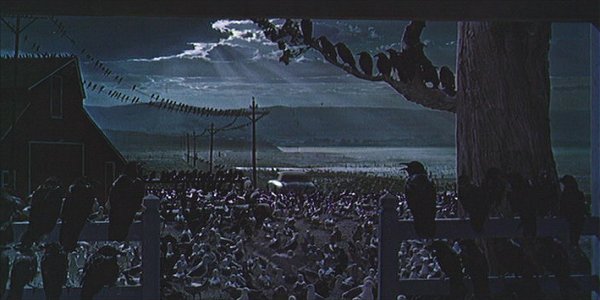

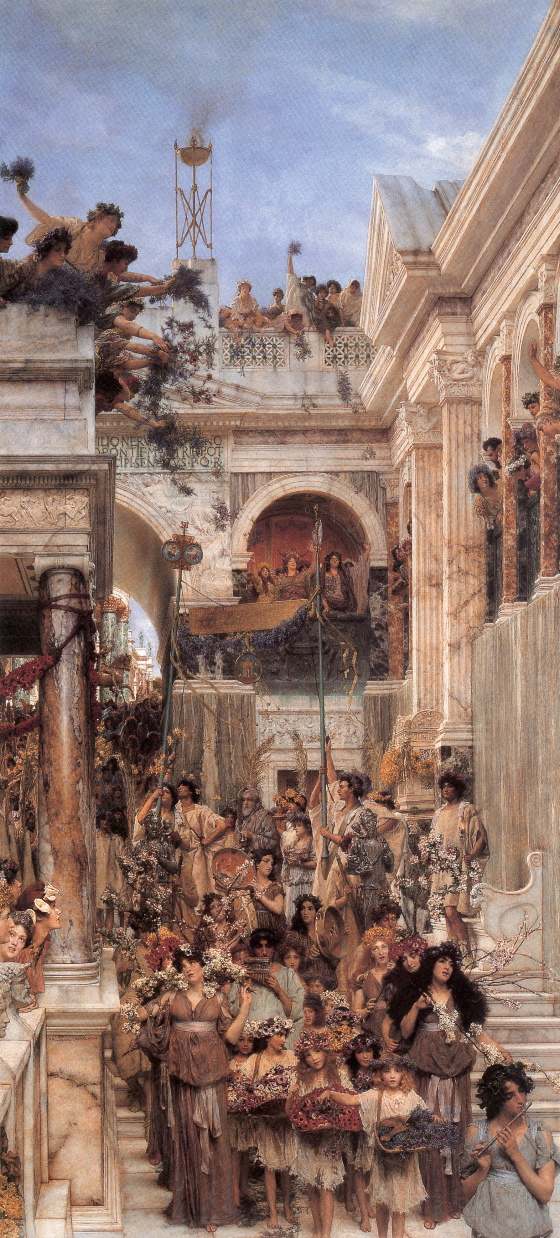

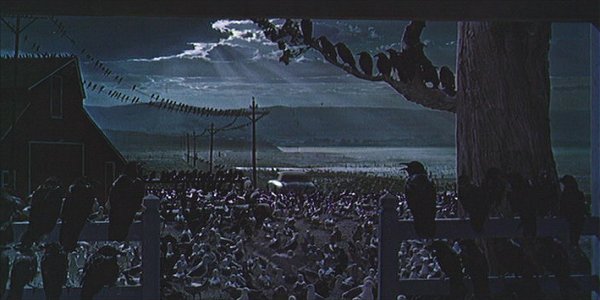

The bird attacks grow more numerous, more lethal, more

surreal. They attack the man and the sister and the mother in their

own home, where the woman is visiting. There seems to be no defense,

no hiding place. But a new family is forming, as the man and the woman

fall deeper and deeper in love, as the sister comes to rely on the

woman emotionally, as the mother slowly softens towards her.

The birds pause in their attack. The family decides

to make a run for it. The sister insists on carrying the lovebirds in

their cage. As they drive away though fields of menacing, roosting,

temporarily placid birds, the mother takes the woman in her arms, in a

mother’s embrace.

The lovebirds in their cage have become a talisman of

salvation — an image of the confinement of commitment, the cage of

family and love, but also of immunity from outright destruction. It’s

like the bait and switch Hitchcock engineered in Shadow Of A Doubt,

where the “oppressive” and suffocating prison of the family, as we see

it at the beginning of the film, is revealed as the only refuge against

forces darker than anyone in that family could ever have imagined.

Only the lovebirds in their cage are free,

provisionally at least. Outside the cage is simply irrational,

meaningless horror. This is not exactly a conservative or romantic

endorsement of committed love and family. Happiness is not really at

stake here, much less moral rectitude or an all-encompassing psychic fulfillment — only

survival. So why is that mother’s embrace at the end of the film so

powerful, so profound, so moving? Because it’s something, set against

nothing.

The newly constructed family drives off jammed into a

small sports car, caged. They incarnate a paradox — are they trapped,

or are they safe? Both,

obviously — but which condition is most important? It’s clear enough

which way the film leans on this issue, but Hitchcock isn’t making any

promises. He insisted that “The End” not appear at the film’s close —

partly as a gimmick (“The birds are still out there!”), partly to keep

the psychic and moral tension alive in the audience . . . but also

partly, no doubt, because he knew subconsciously that he would return

to the female protagonist of this film again, would explore her

existential jeopardy in greater depth, which he did in Marnie, using the

same actress, playing a very similar lost soul in search of a mother’s

embrace.

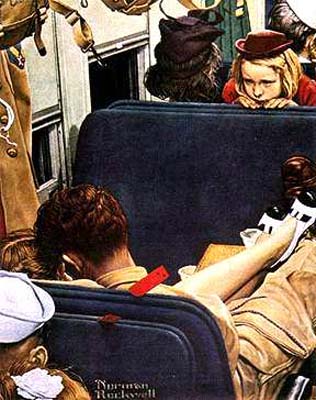

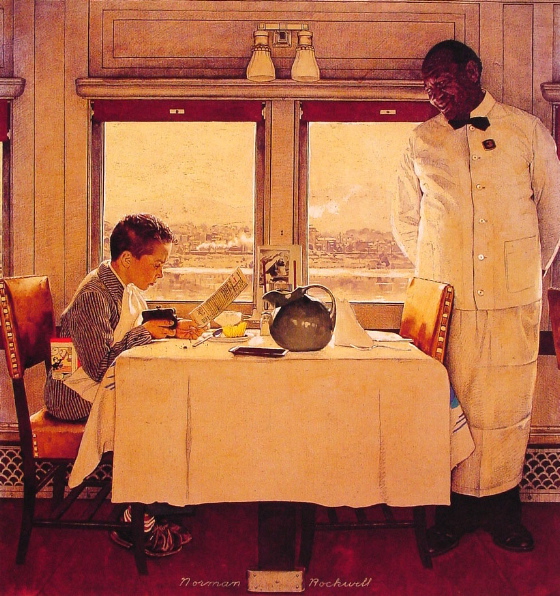

The hidden, poisoned springs of many Hitchcock films run through the

pathology of dysfunctional parents, shattered, perverted families,

wrecked marriages — and the provisional redemption these films offer

often involves new families reconstructed on the ruins of old

ones. Hitchcock’s view of the family, all families, was ambiguous

— and his passionate defense of the family as a bastion against

terror, against meaninglessness, was inflected by this ambiguity.

Even so, his view was inaccessible to many critics, like Wood, who

were, for personal and political reasons, deeply suspicious of the

family as a social phenomenon — an attitude that became fashionable,

almost a matter of faith, among 20th-Century intellectuals. Wood

wanted to analyze The Birds

as a vision merely of conflict between order and disorder, missing the

fact that, for Hitchcock, this conflict was centrally bound up with the

idea of family.

Hitchcock was canny. He knew that society cannot face its deepest

concerns, its deepest fears, directly. He knew that those fears

had to be displaced in art, given an indirect expression — blamed, as

it were, on the birds.