Click on the image to enlarge.

Category Archives: Art

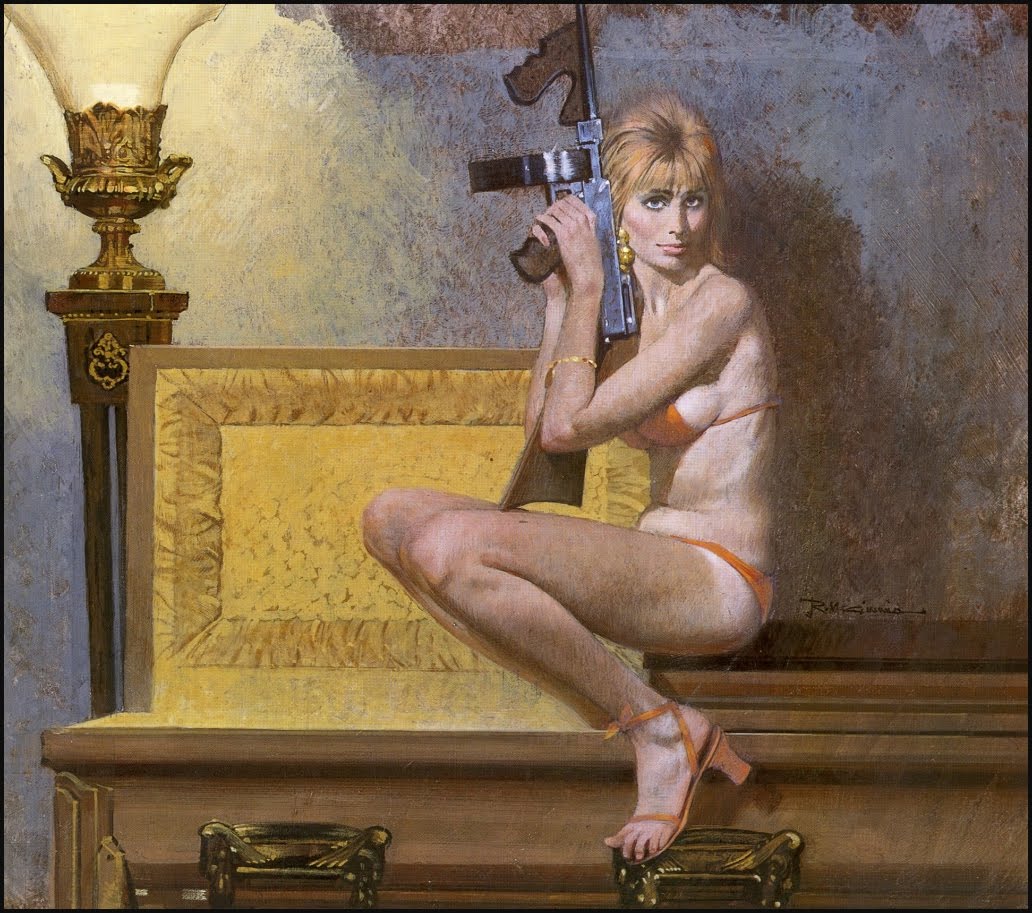

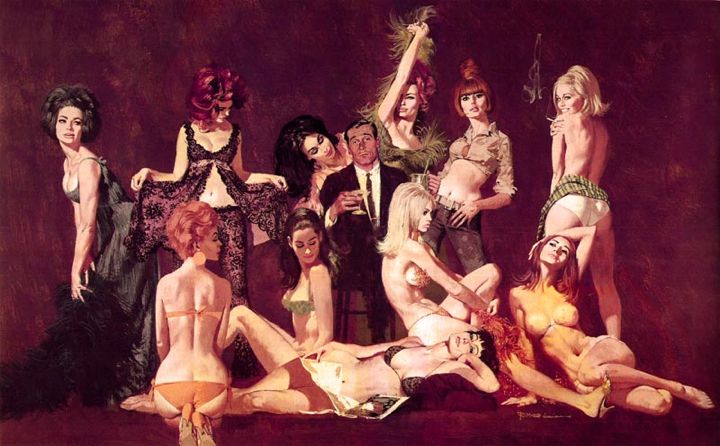

A ROBERT MCGINNIS FOR TODAY

A NORMAN ROCKWELL FOR TODAY

A NORMAN ROCKWELL FOR TODAY

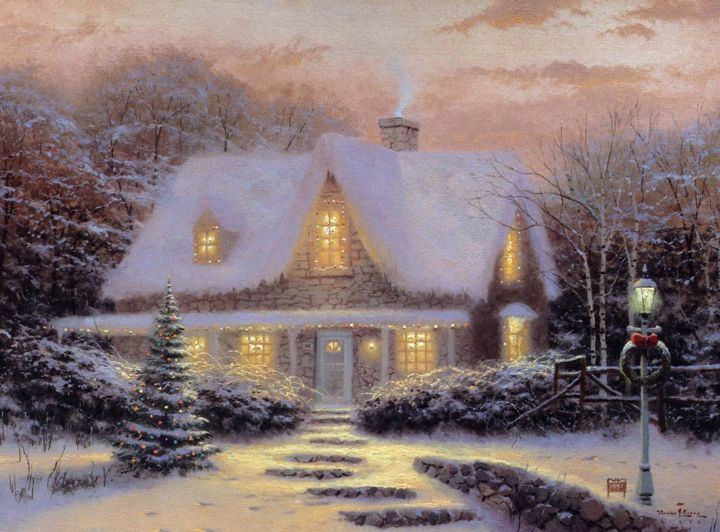

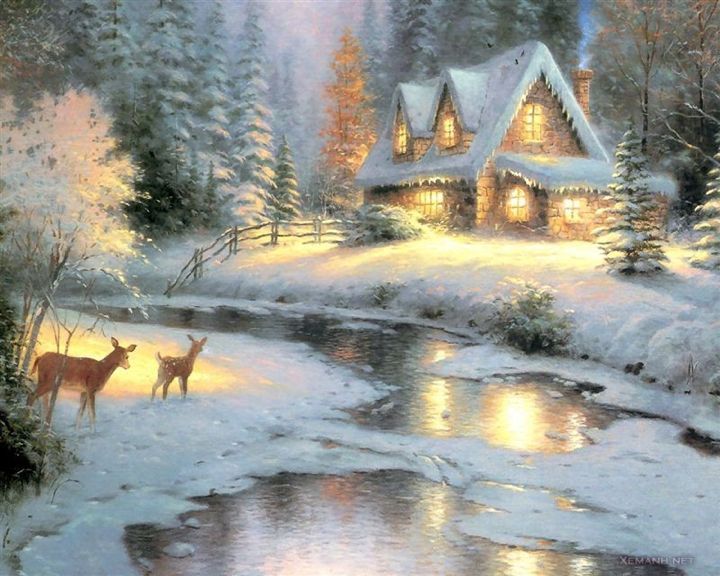

MORE ON THOMAS KINKADE

Joan Didion wrote:

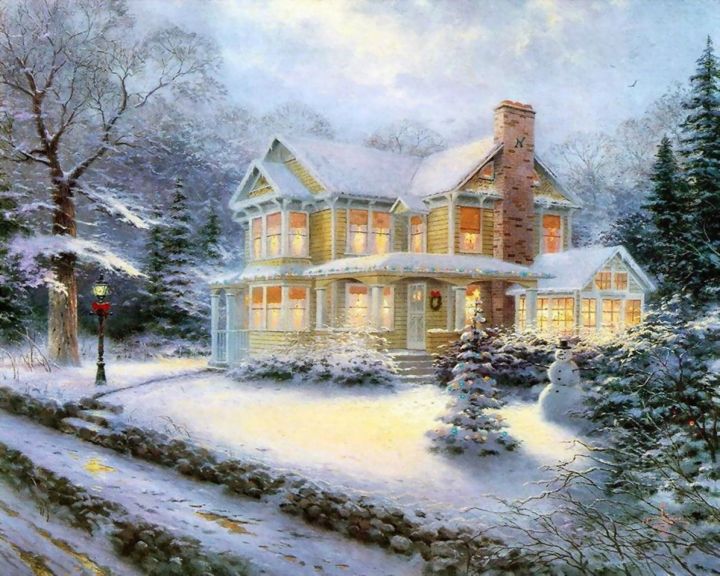

A Kinkade painting typically featured a cottage or a house of such insistent coziness as to seem actually sinister, suggestive of a trap designed to attract Hansel and Gretel. Every window was lit, to lurid effect, as if the interior of the structure might be on fire.

I myself don’t feel a sinister aura in Kinkade’s work — the home pictured above seems like a cheerful and inviting place — but Didion at least identifies a kind of power in his images.

It’s interesting, too, that no homey refuges like the ones he depicted were accessible to Kinkade in real life. He suffered from depression, over money, over the reception of his work by critics and over a painful divorce. He struggled with alcohol addiction, had had a relapse just before he died, and the cause of his death was an accidental overdose of anti-anxiety medication and drink.

His images of well-lit, inviting homes are usually pictured from the outside, often with paths through the winter snow leading towards the warmth inside. He saw himself apparently as forever stalled on the path, like the deer in the image above, on the outside, dreaming of a comfort that would always be just beyond his reach.

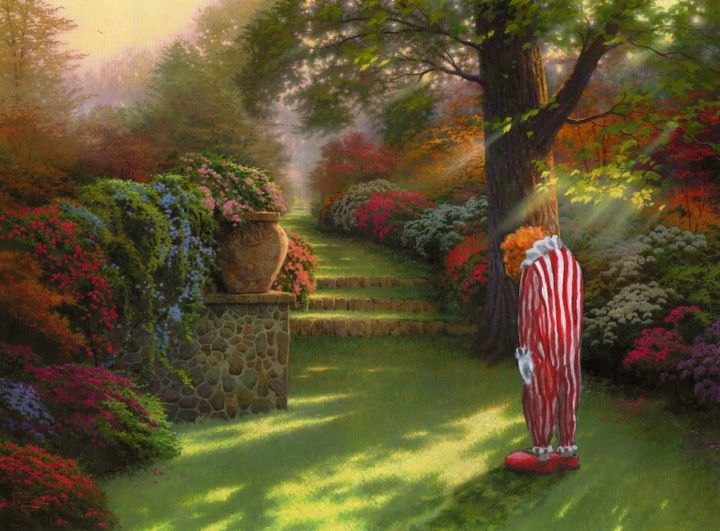

Kinkade rarely created explicitly surreal images, but look at this one:

It’s not terribly compelling as a painting but it may well represent a deeply-felt self-portrait. It’s called Pathway To Paradise — a pathway the artist, in the person of a sad clown, feels he will never walk, is perhaps not worthy to walk.

[You can read some earlier thoughts on Kinkade, with interesting comments, here — Light.]

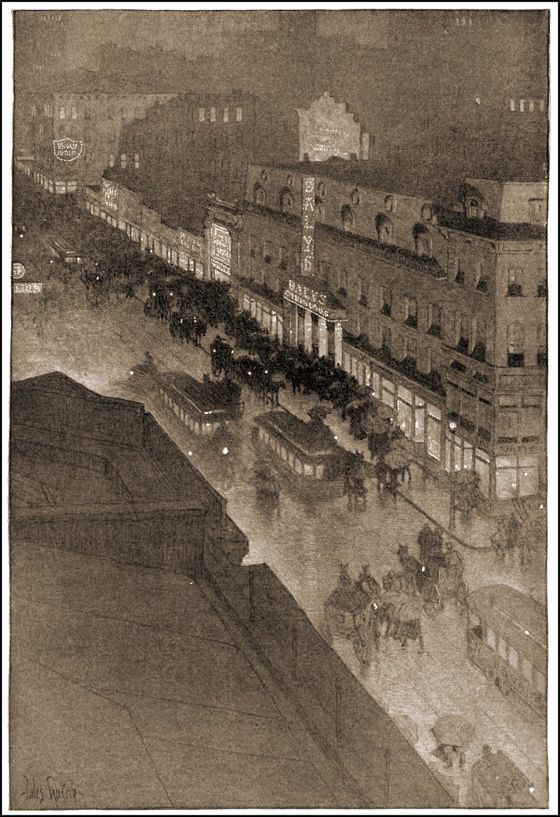

A JULES GUÉRIN FOR TODAY

A Bit Of Broadway, Scribner’s Magazine, 1905.

[Via Golden Age Comic Book Stories, an ever wondrous site.]

SPOON DRESS

The painting above lives in the New Orleans home of my friends Adrienne and Bill. It’s by Rebecca Rebouché, a Louisiana artist:

I got to meet her on my recent visit to New Orleans and see more of her work at the Jazz Fest, where she had a booth.

You can see a selection of her work at her web site — Rebecca Rebouché. It uses folk motifs and surreal juxtapositions to create an eerie combination of the whimsical and the mystical. It’s sweet, with dark and unsettling undertows — like flowers found deep among the twists and turns of a haunted bayou.

It’s all quite wonderful, but Spoon Dress is the one that stayed with me most insistently on my journey home, mixing with the memories of my magical time in The Crescent City — the girls in their summer dresses dancing to sinuous swamp music, a spoon breaking the crust of the legendary bread pudding soufflé at Commander’s Palace.

[All images © Rebecca Rebouché]

A MARTIN LEWIS PRINT FOR TODAY

Rainy Day, Queens, 1931.

My friend Jae Song turned me on to this guy — he did brilliant work. Why have I never heard of him before? Why are there no books that collect his prints — just a catalogue raisonné with tiny reference reproductions?

This image owes something to Caillebotte’s Jour de Pluie à Paris of 1877:

LIGHT

Thomas Kinkade, who painted the image above, died yesterday at the age of 54. It has been claimed that 1 in 20 homes in America has a Kinkade image of one sort or another — a print, or something on a plate or tea towel. Kinkade hawked his work on QVC and commercialized it in every way he could think of.

It has also been claimed that his work is junk, but it’s not junk. Its draftsmanship is serviceable, its painterly qualities are mediocre but professional — good enough to serve his purposes, which are emotional. He called himself — actually trademarked himself as — the “Painter Of Light”, and he used light to summon back the feelings of coziness that a home or a garden can give, with the immediacy those feelings have in childhood.

Kinkade associated light with his Christian faith, using it as a symbol of warmth, welcome and comfort in both his secular and religious paintings. He had a special fondness for Christmas scenes.

Kinkade’s talents and aims were modest, but in the very narrow territory he staked out for himself, he was an artist worthy of respect. His gift reveals itself in that brief twinge of nostalgia, of remembered enchantment, we feel when we first see one of his more successful images — before our critical faculties dismiss it as second-rate, or before it becomes part of the furniture.

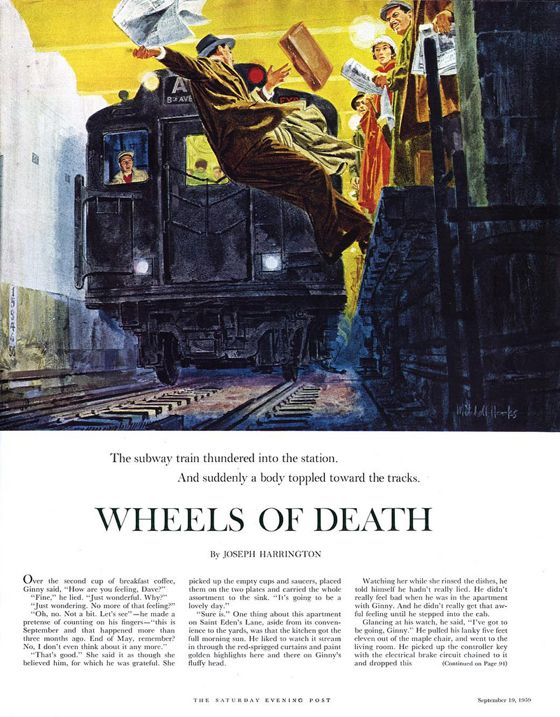

A SATURDAY EVENING POST ILLUSTRATION FOR TODAY

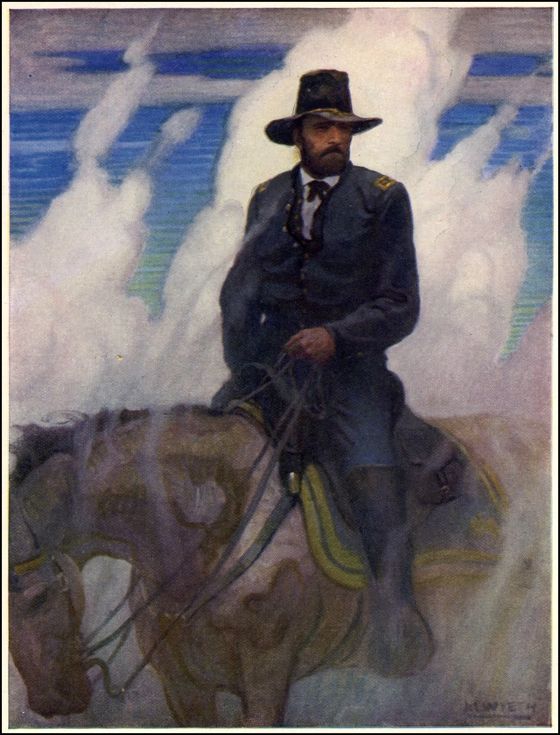

AN N. C. WYETH FOR TODAY

Ulysses S. Grant

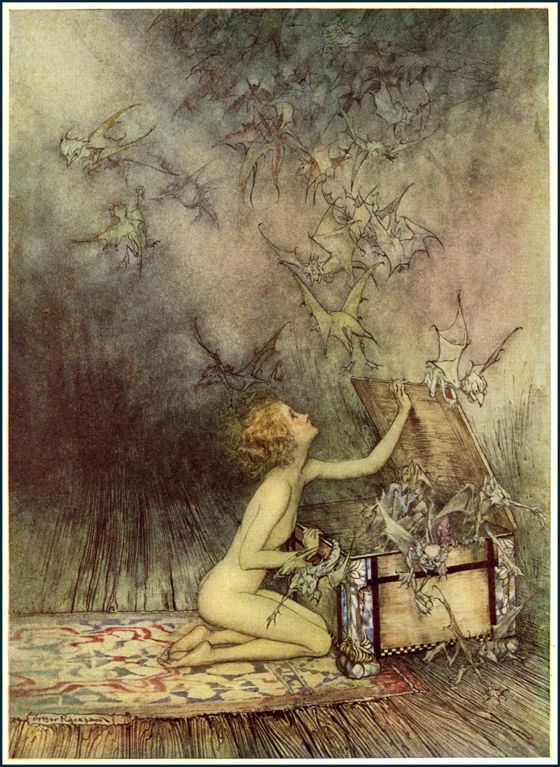

AN ARTHUR RACKHAM FOR TODAY

MY LIFE

Hectic, tiresome . . .

A GIL ELVGREN FOR TODAY

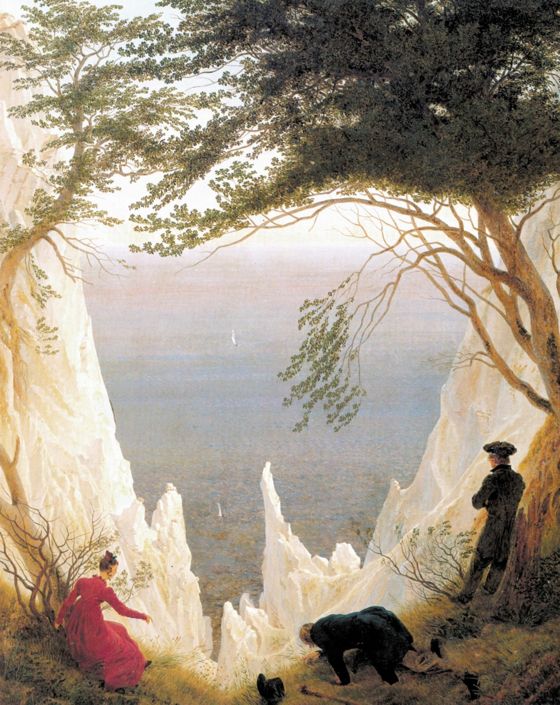

A CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH FOR TODAY