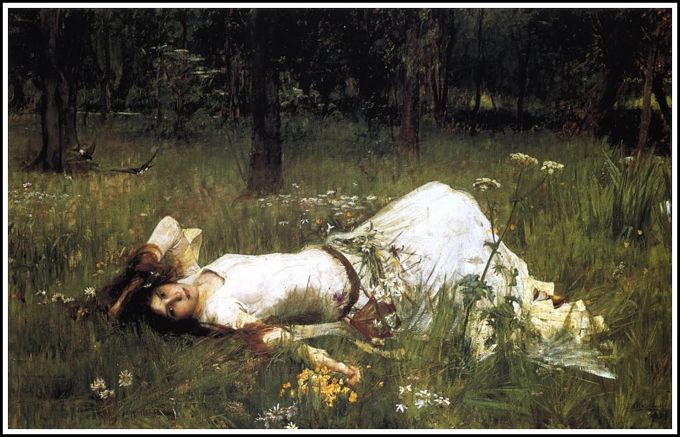

Ophelia, 1889

Ophelia, 1889

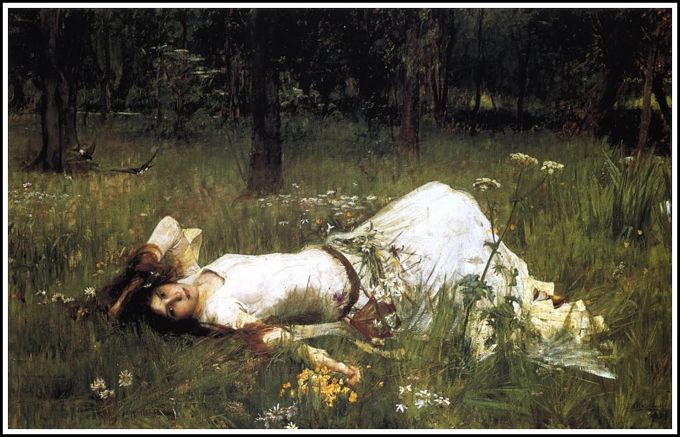

Illustration, For Men Only magazine.

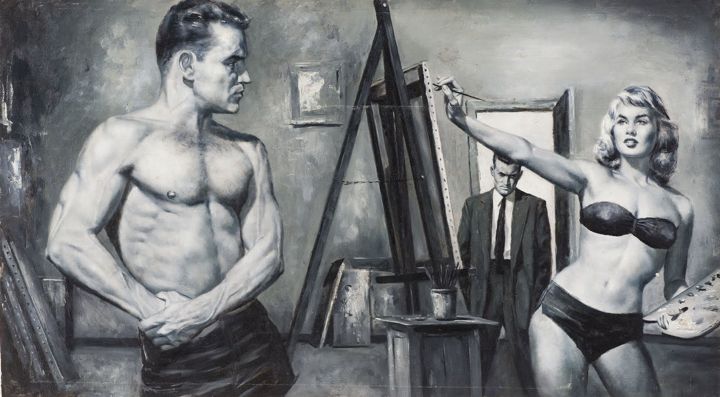

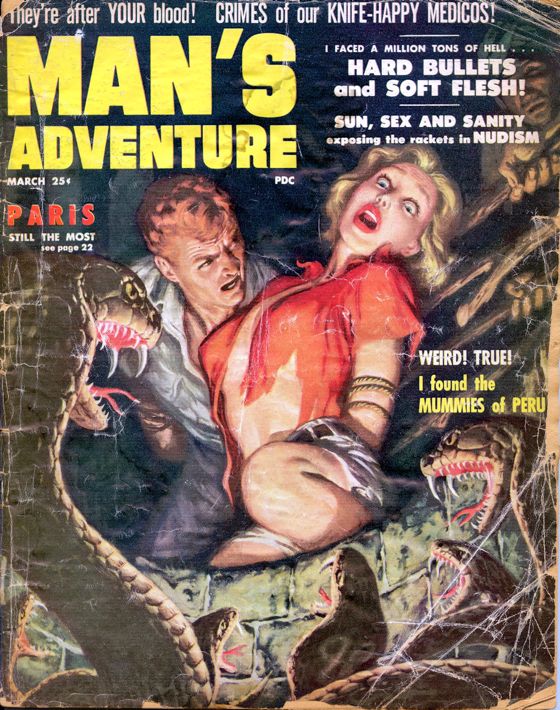

“The Knockdown”, Men's Adventure magazine illustration.

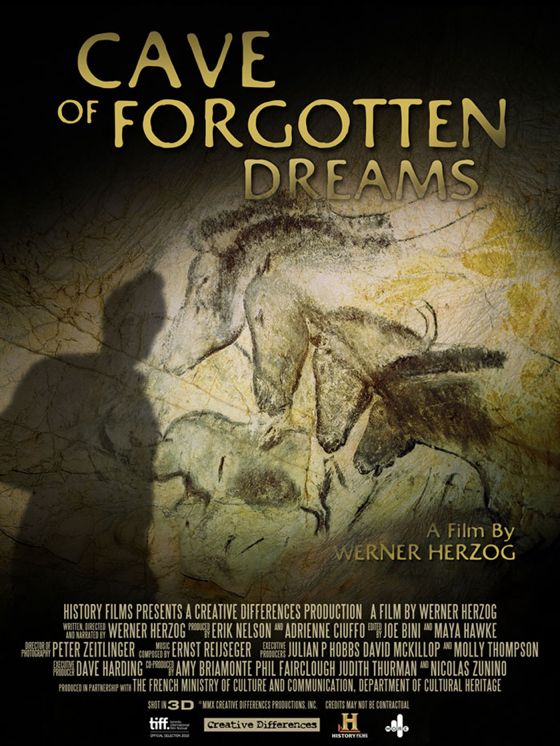

Yesterday afternoon I sat in a dark movie theater in the middle of the Mojave Desert and, thanks to some 21st-Century technology, stared into a dark cave in the south of France whose walls contain what are thought to be the earliest paintings by human beings ever discovered, some 30,000 years old.

I was, of course, watching Werner Herzog's 3D documentary Cave Of Forgotten Dreams. Because of the precious nature and fragility of the cave paintings, the public has never been and never will be allowed to visit the cave, which is accessible only to scientists and historians, but Herzog was allowed to film it to show off its wonders to the world.

The 3D process he used is illuminating, not only because it conveys a visceral sense of the spooky cave environment but also because the artists who made the paintings used the irregular surfaces of the cave walls as elements of their work, often suggesting the physical mass of the animals they depicted, giving the images at times the quality of relief sculptures.

One has to strain to imagine the age of the paintings because they do not look old. They are well preserved, because the cave was sealed off by a rock slide about 10,000 years ago, but the art itself is fresh and alive, and breathtakingly beautiful. The images pulse with desire — they mostly depict animals that were hunted by Paleolithic men for survival — but also with awe and respect. The animals are rendered with powerful suggestions of movement and grace, their beauty as living creatures fully appreciated.

Here, for example, are the earliest painted representations of horses, and they can stand as works of art alongside the horses of the Parthenon Frieze, the Byzantine Horses of San Marco, the horses in a John Ford film. They summon up the vital spirit of horses in the flesh and in movement.

Human beings have created no greater works of art in the 30,000 years that have passed since “primitive men” crafted these images. This is humbling in one sense, but also invigorating. The images remind us of what is distinct about our species, this ability to make not just useful things, of increasing complexity, but sublimely beautiful things, of inexhaustible complexity. It's a complexity that transcends the material plane, and can only be called spiritual, and it's found, fully developed, in Chauvet Cave.

Our ancestors were fully human when they made these works of art — when one of them stenciled the outline of his hand on the cave wall — and we can look at them to remind ourselves what being fully human means.

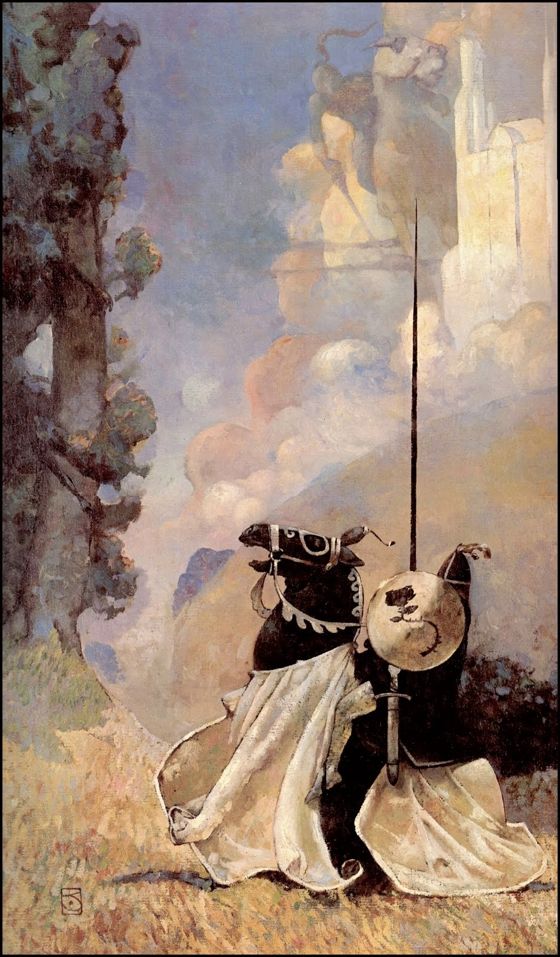

Jeffrey Catherine Jones died yesterday at the age of 67. Born male, Jones had a sex change operation later in life. Her style of illustration often echoed Frank Frazetta's, though she had great range and Frazetta once called her “the greatest living painter”. The influence must have gone both ways.

Jones admired the illustrators of the generation before hers and Frazetta's, especially those of the Brandywine school, and the image above, Black Rose, from 1972, is a kind of homage to the greatest of the Brandywine artists, N. C. Wyeth.

Paperback cover, The Evil Of Time, 1967.

Mishap In the Dining Room

“Freedom Girl's Iron Curtain Escape”, For Men Only cover, June 1964.

[With thanks to Archie Waugh.]

Tea Room

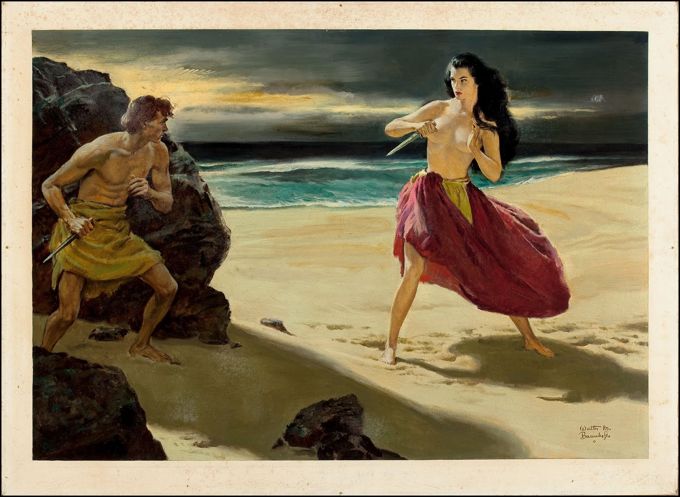

The Pirate Queen — aaarrrgh!

John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic, never consummated his marriage, which was annulled after a few years. He said his wife was “not as other women”, physically, and one biographer has speculated that Ruskin was put off by the sight of his wife’s pubic hair. Knowing the female nude only through art, he might never have seen such a thing, and might have thought it was an anomaly. His wife later remarried and had several children, so she must have been “as other women” in most respects.

The convention in most Western art, before the 20th Century, has been to present the female genitalia as a hairless mound of flesh without an orifice. (The ancient Greeks, who found the depiction of female genitalia shocking, usually presented them draped, rather than denatured.)

One major convention in modern fashion photography is to present half-clad women who are almost revealing, threatening to reveal, but not quite revealing their genitalia, or nipples.

The photograph at the head of this post is from the notorious ad campaign for American Apparel, which made a splash by violating this convention. It shows pubic hair, and other American Apparel ads have shown nipples.

I myself find this explicitness refreshing. There’s tease involved — the ads don’t show everything — but they don’t fetishize the naughty bits. Indeed, they celebrate them. They also show women as whole beings, rather than as custodians of desirable but forbidden body parts.

Most fashion photography uses sex to sell clothes. To me, the American Apparel ads use clothes to sell sex, which is often the real point of clothes, and seems a far healthier approach.

Rescuing the female body from commercialization and commodification is one of the great tasks that lie before our civilization. The American Apparel ads can’t be said to contribute much to this task, but perhaps it can be said that they’re a modest step in the right direction.

Illustration for The Saturday Evening Post.

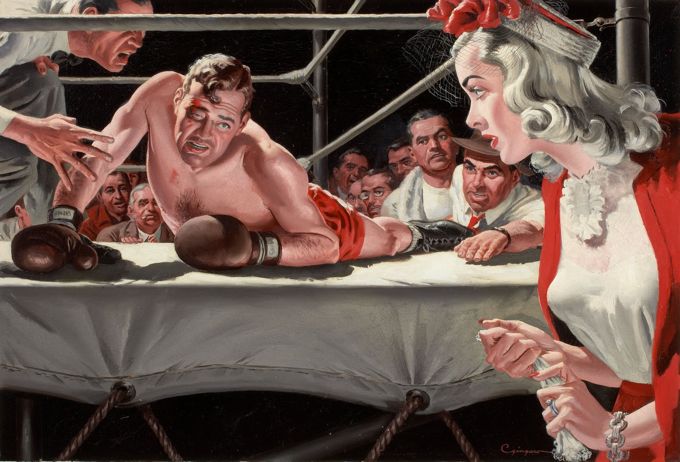

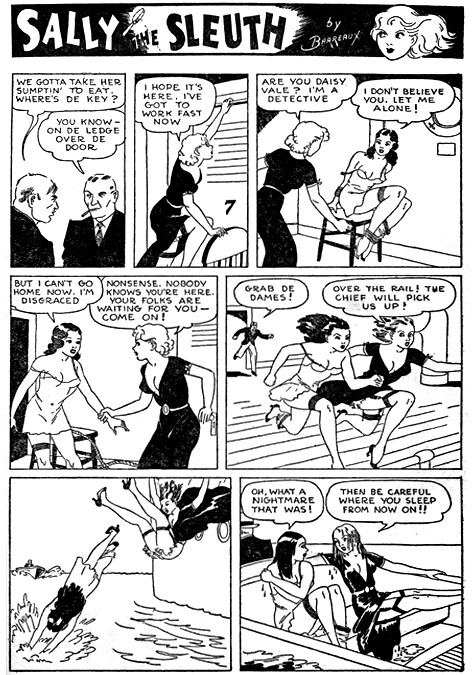

By Syd Shores, from 1958.

From 1936, when they still knew what “spicy” was all about . . .