Thanks to Golden Age Comic Book Stories . . .

Thanks to Golden Age Comic Book Stories . . .

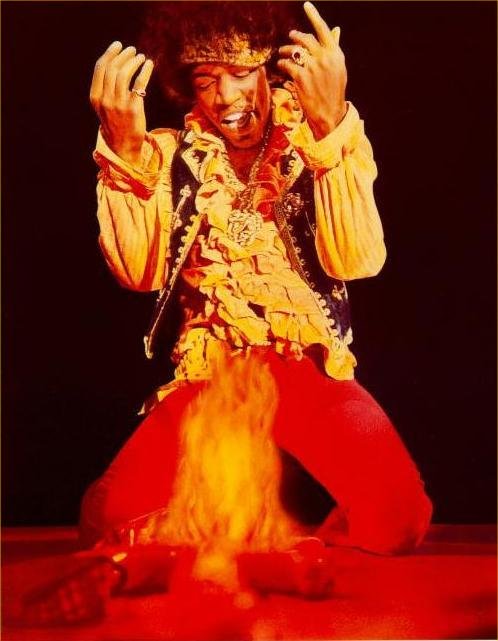

I was 9 when the Sixties began, 13 when they began in earnest with the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the advent of The Beatles. The decade sucked up all of my teenage years and brought many cultural shocks, from the Civil Rights Movement to Dylan's minatory prophesies, more assassinations, fighting in the streets over the Vietnam War and the sublime derangements of Jimi Hendrix and Jean-Luc Godard.

I went off to college in the Bay Area in 1968, grew my hair long, wore Nehru jackets and sandals made out of tire treads. I eschewed illegal drugs — my little stab at non-conformity — but drank plenty of Ernie's Burgundy and took up the smoking of cigarettes. I hitch-hiked all over the country and once panhandled for spare change on a street corner — living out a fantasy of dereliction, all the while knowing that I had a nice middle-class family to return to if things ever got really desperate. (Such was the depth of hippie rebellion.) I was at Altamont where everything came crashing down in spectacular fashion.

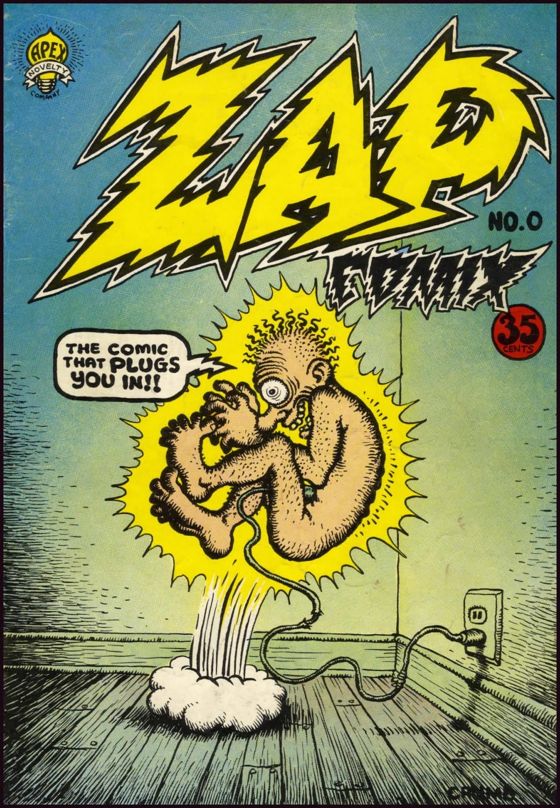

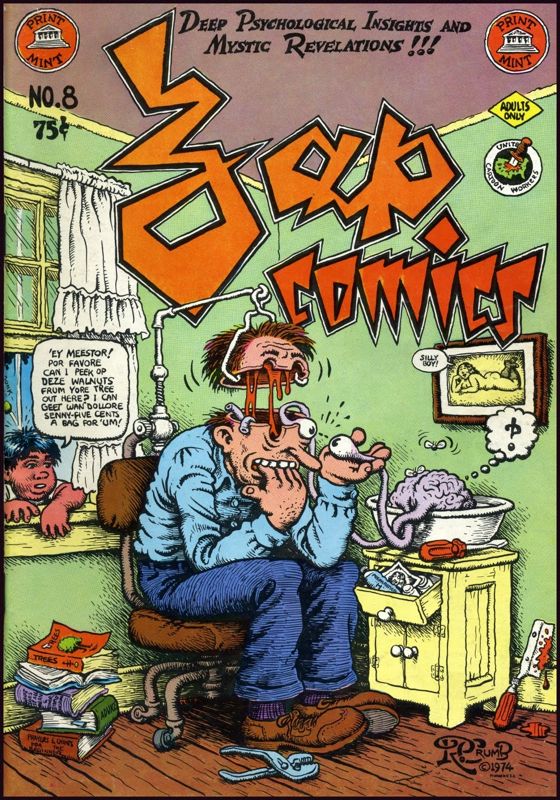

In all that madness, I don't think any cultural artifacts impressed me as deeply as the works of R. Crumb. When I bought my first batch of Zap Comix at the City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco and began to devour them, I had a sense that I would never look at America and American popular culture in quite the same way again — and I never did. Crumb represented a permanent mind-fuck.

On his recent trip to Paducah, Kentucky, Paul Zahl passed through Nashville and made a special trip to see . . . a Presbyterian church done in a very strange style. He writes:

This photo is a little dark, but was the best I could do given the

available lighting. Together with the First Presbyterian Church, also known as the Old Whaler's Church, at Sag Harbor, Long Island, this is one of the earliest Egyptian

Revival churches in America. Now known as the Downtown Presbyterian Church, it was designed by William Strickland in 1849.

It is directly across, or almost directly across, from the Capitol, in

the center of Nashville. Because Presbyterian churches are rarely open

during the week, I was doubtful that my friend Ray and I could get in but . . . dashing around the block to the church office, I found the

sexton. She was just “closing up”. Fortunately, she opened the

church, and I got in.

It is amazing. Central pulpit, large organ and organ case, classic

Communion table under the pulpit. I looked for the Mummy behind

the pulpit, but no dice. I am believing that Kharis rests directly under the pulpit. Wonder, too, whether the preaching in this church is

sufficient to waken him. I hope so . . . or maybe I don't.

I must say that the Egyptian Revival style in early 19th-Century American architecture was more or less off my radar, and the fact that it was used for Presbyterian churches seems delightfully odd.

If you are, like me, a fanatical admirer of the much mocked and despised 19th-Century academic painter William Bouguereau, you will want to save your pennies for an extraordinary new work devoted to his art, the Catalog Raisonné On William Bouguereau. It's a massive, and very expensive, two-volume biography and catalog raisonné listing and reproducing all his known paintings. Beautifully printed and bound, with hundreds and hundreds of mostly excellent color reproductions, it will take your breath away.

Devoting this much attention to Bouguereau is almost an act of defiance — a way of asserting his importance in the face of decades of scholarly scorn. His popularity has never needed defending, despite the unwillingness of museums to show his work throughout most of the 20th Century. People have always loved his images. Now, prices for his paintings are escalating at an astonishing rate, and the Musée d'Orsay has recently acquired five new works by him, including L'Assault, pictured above, and Compassion, pictured below, which will hang on permanent display with the two the museum already owned.

I pre-ordered a copy of the Catalog ages ago, at a greatly reduced price, and waited patiently as its deadline for publication was constantly pushed back. I confess there were times when I wondered if the project was all a fantasy. But the set arrived a couple of days ago, and it was worth the wait.

Today, post-publication, the set will cost you $350 — from the Art Renewal Center, which co-sponsored the project — and many months of your time to browse and read. (If the price is too daunting, the Art Renewal Center plans to donate copies to libraries, so you'll be able to get your hands on one for free eventually.) The Catalog may spark a reappraisal of Bouguereau's work in the art world, or not — that hardly matters. It will certainly expose many new people to the work, and promote a consequent suspicion of the judgments of the art world.

Bouguereau's visions are meticulously conceived and executed, and often quite mad. They are endlessly astonishing and entertaining, and sometimes moving. They have a regard for sentiment and a connection to popular taste that most painting lost in the 20th Century, but will reclaim someday. Bouguereau is not about the past — he's about the future. Get to know his work and you'll see why. Virtuosity combined with pleasure and surprise never goes out of style, at least not for too long.

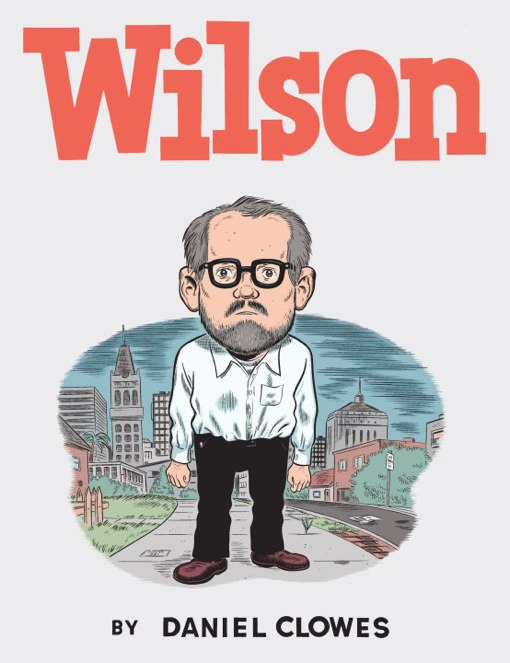

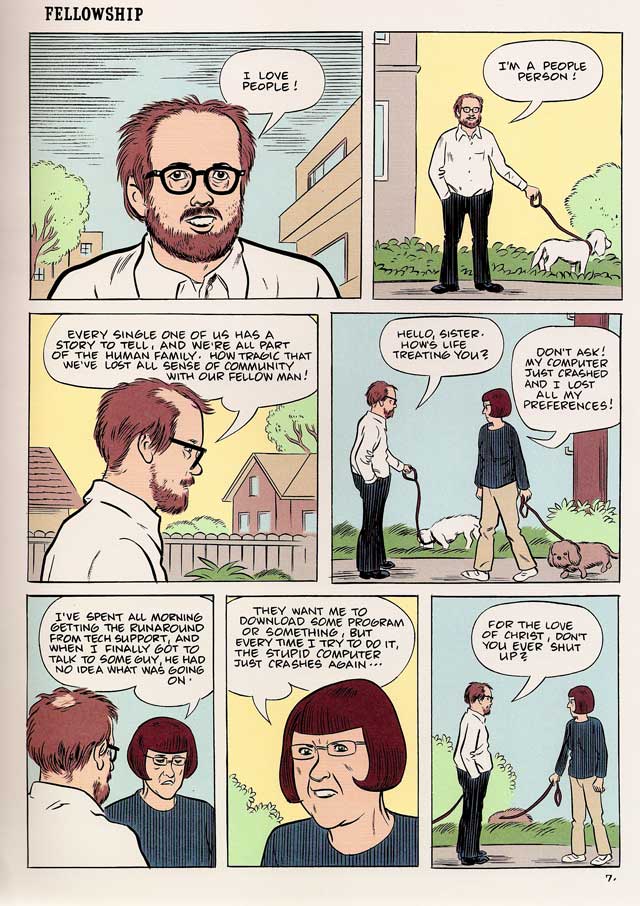

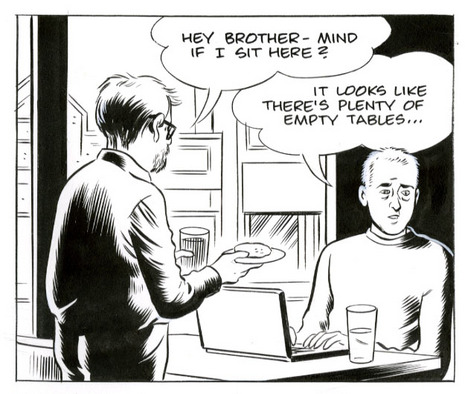

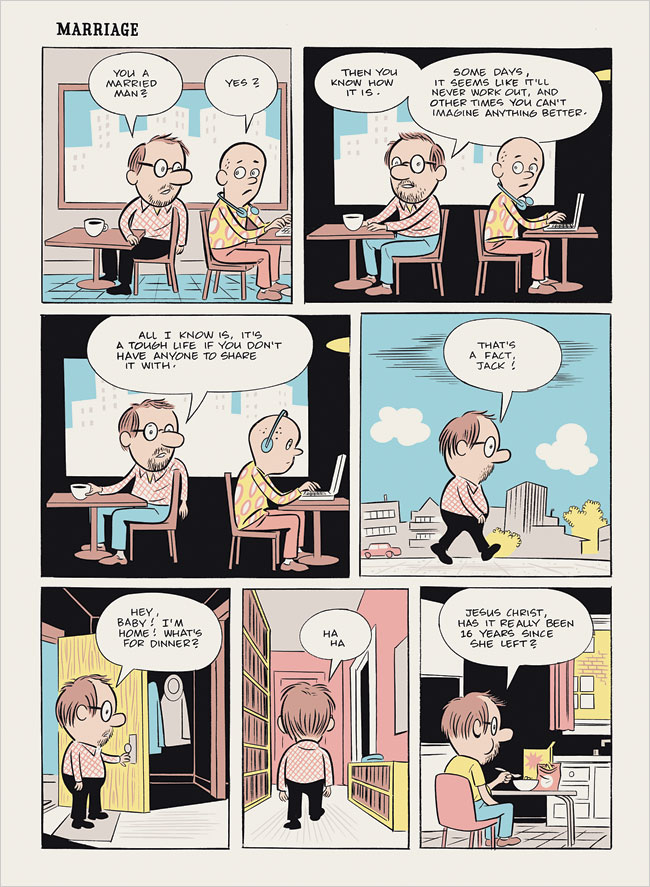

Wilson is a new graphic novel by Daniel Clowes, the author of Ghost World. Clowes is one of the great fiction artists of our time, and Wilson is his darkest work to date.

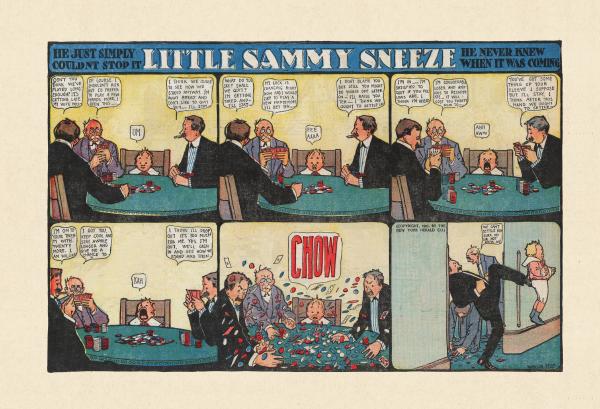

It's a sort of existentially bleak version of Winsor McCay's Little Sammy Sneeze, a strip McCay drew in the years before he created the legendary Little Nemo.

In McCay's strip, Sammy finds himself in a new place and situation every week, and as events unfold around him he starts a build-up to a sneeze, which explodes eventually with awesome power, severely disrupting or destroying everything around him. It's a strange idea for a strip, not really funny but oddly satisfying, in an anarchic way.

Wilson consists of self-contained one-page episodes all featuring a single protagonist, Wilson, a lost soul. Wilson has insights into life or hopeful encounters with other people all of which explode by the end of the page in an outburst of self-deception or cruel narcissism. As these emotional dead ends accumulate, Clowes constructs a portrait of genuine and utterly hopeless despair. Kierkegaard said that “the precise quality of despair is that it is unaware of itself”, and such is Wilson's.

It's not satisfying on any level, but rather heartbreaking, infuriating, sickening. It sucks us into the black hole of Wilson's psyche and makes us feel that there's no way out of it. It's slightly terrifying.

A life's narrative emerges from the self-contained episodes, a story of sorts, and they are varied by being done in contrasting styles, usually in Clowes's familiar naturalistic mode, using color panels, but sometimes in black-and-white pages and sometimes in crude comic-book caricature style. The variations only serve to emphasize the relentless coherence of Wilson's spiritual pathology.

It's a profound meditation on contemporary angst and one of the finest of all graphic novels.

Willem van de Velde, The Gust, 1680.

My friend Paul Zahl reminds me that as teenagers we used to visit this painting often at the National Gallery Of Art in Washington, D. C. We loved it then and I still love it.

The sight of the sea over the railing of a ship lifts the spirit, fires the imagination.

Illustration by Franklin Booth from 1914, via Golden Age Comic Book Stories.

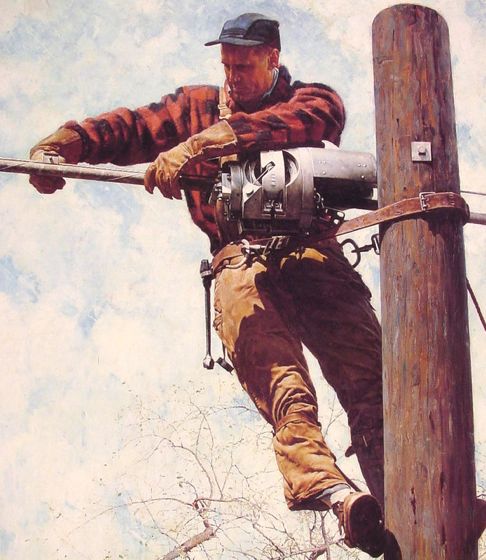

He is a lineman for the county.

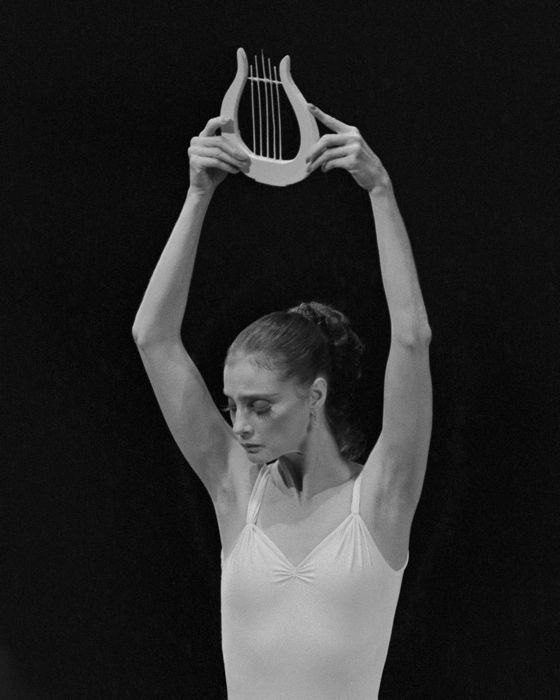

[Image © Paul Kolnik]

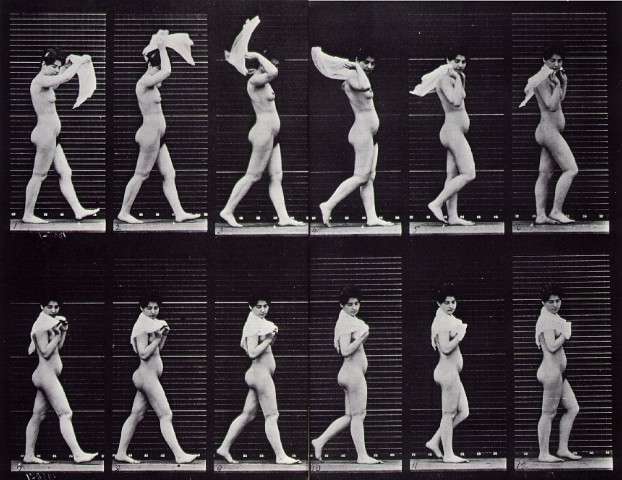

I learn from Oliver Sacks that neurologists use this phrase — the kinetic melody of movement — to describe the naturalness and fluidity of normal human movement. They call a halting, broken movement, caused by something like Parkinson's disease, a kinetic stutter.

As Sacks explains it, “When we walk, our steps emerge in a rhythmical stream, a flow that is automatic and self-organizing. In parkinsonism, this normal, happy automatism is gone.”

Dance elaborates on this natural kinetic “melody” in order to celebrate it, and it is something worth celebrating, as a sign of health and prowess, crucial to early human societies, especially ones based on hunting.

[Image © Paul Kolnik]

Like musical melodies, based undoubtedly on the pleasing qualities of human speech, especially in the unique voices of kinfolk and tribal allies, dance can become almost an end in itself — but it always retains an echo of the simplest kinetic melody, the song sung by any human body moving through space.

Sculptors, like Augustus St. Gaudens (above), and photographers like Paul Kolnik, who did the black and white images of the New York City Ballet here, can freeze motion in such a way that it implies the whole melodic arc of a movement.

When a filmmaker puts a frame around some part of the world, she is helping define a space, and thus helping us read any movement through it as a kinetic melody. Such melodies can, by the choreography of the movement, become almost symphonic, in the way classical ballet can. Good Westerns, which enlist the noble and elegant kinetic melodies of horses, are always symphonic in this way.

Every great filmmaker knows, if only intuitively, that she is really making a kind of music with her images.