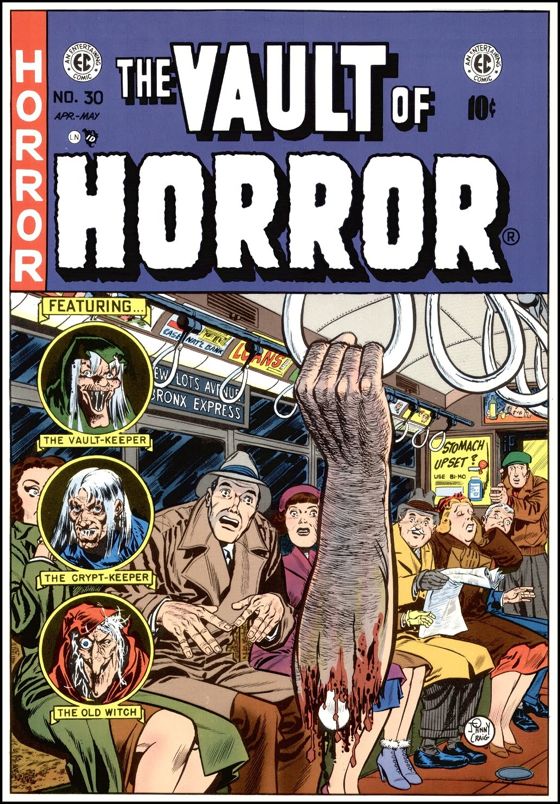

Paul Zahl remembers Dr. Jules de Grandin, occult detective, and his creator Seabury Quinn:

IN MEMORIAM:

Jules de Grandin

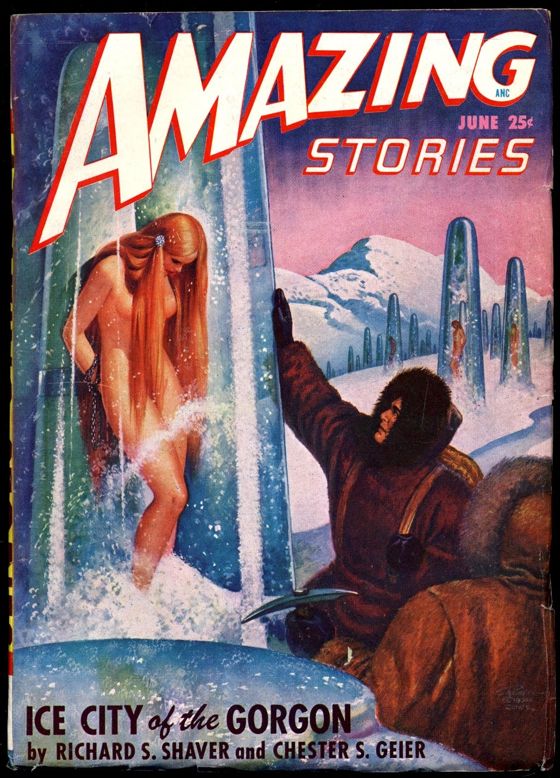

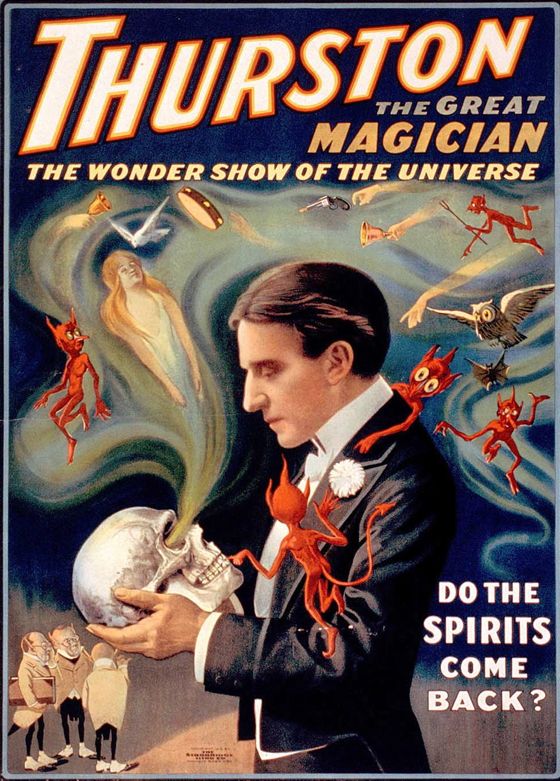

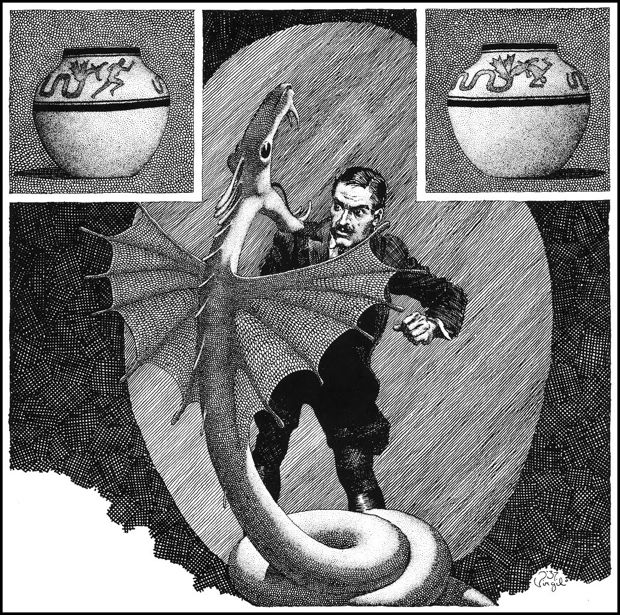

The homage to the Weird Tales illustrator Virgil Finlay (1914-1971)

which has appeared on the Golden Age Comic Book Stories website (June

16, 2010) is evocative and beautiful, not to mention haunting.

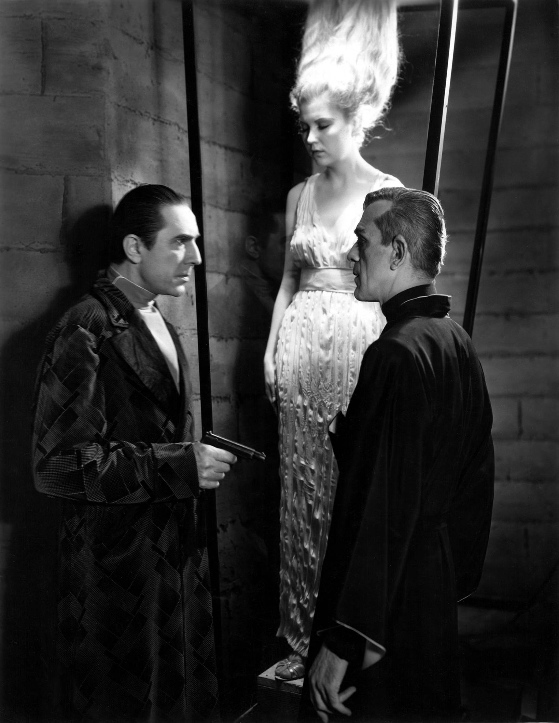

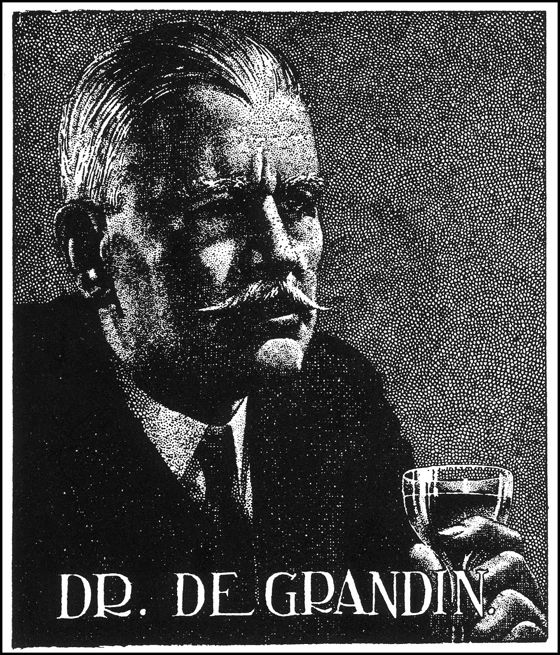

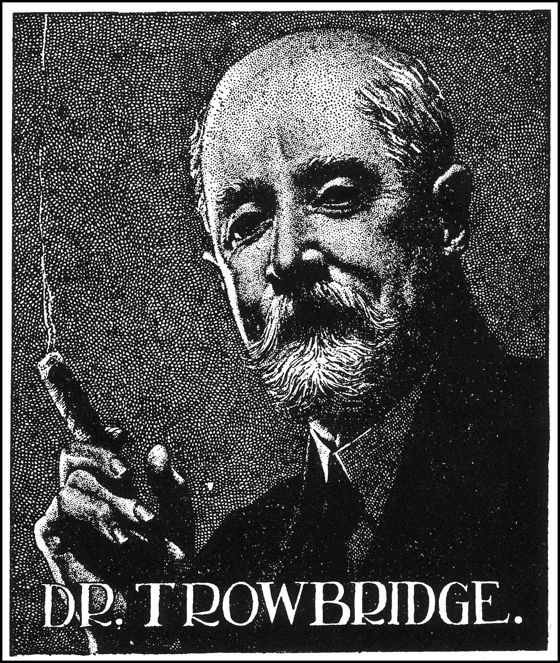

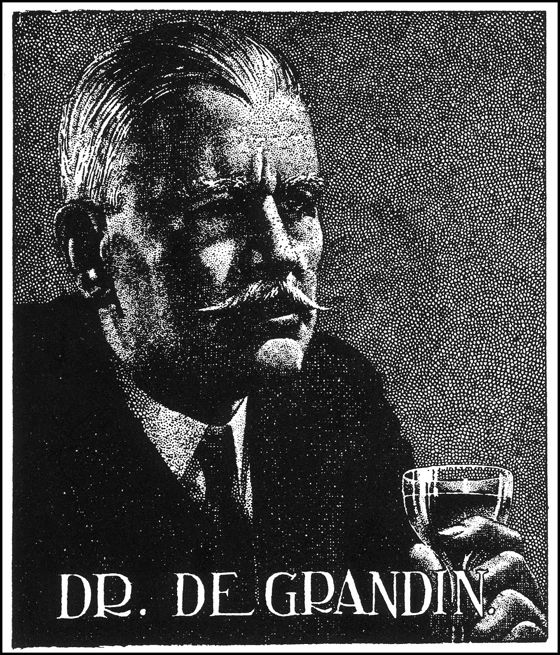

Square in the middle of the illustrations presented are two old

portraits, from the late 1920s, of “Dr. de Grandin” and “Dr.

Trowbridge”. These were great men of the magazine Weird Tales; and I

would like to give a short eulogy to one of them. He is Jules de

Grandin, occult detective extraordinaire.

Jules de Grandin was a French-born private investigator who lived in

the fictive town of Harrisonville, New Jersey, outside of New York

City. He was the creation of the writer Seabury Quinn (1889-1969), who

directed funerals by day and wrote horror stories by night. Quinn had a

fine eye for the macabre detail, and an imagination that created

unusual supernatural situations that were rarely disgusting but often

eye-catching. They lurked in the memory.

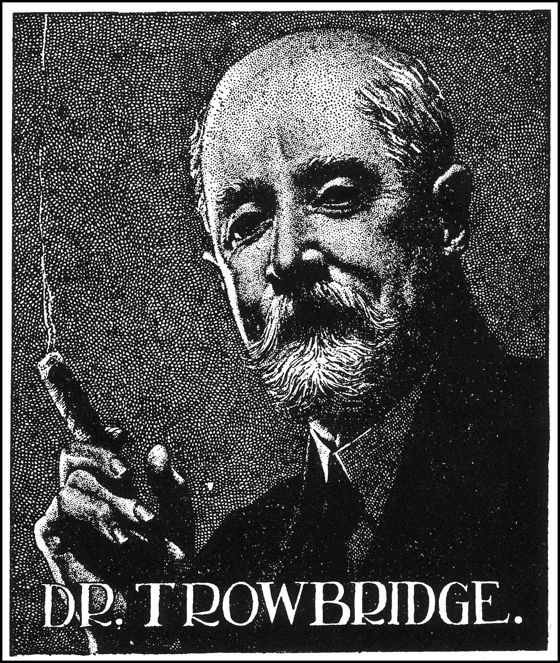

The occult detective was usually accompanied by his medical friend Dr.

Trowbridge [below], a fairly sceptical “liberal”, if occasionally moralistic.

They lived and worked in Harrisonville, which, incidentally, was pure

James-Gould-Cozzens country. That is, the old established families were Episcopalian; the professional ones,

Presbyterian or Methodist; the immigrants, mostly Italian and Central

European, Catholic; the blacks and poor-whites, Baptists or

non-denominational evangelical. I single out the religious aspect,

because most of the Jules de Grandin stories involve occult incursions

into real life that are ultimately defeated by some sort of religious

talisman.

Jules de Grandin is highly educated, most cosmopolitan, and you can't

pull the wool over his eyes, ever! He reminds me a little of Agatha

Christie's more mainstream character, Hercule Poirot. But he, unlike

Poirot, deals with vampires (in F. Scott Fitzgerald suburbs), werewolves

(in Little Italy), or Asian gurus and yogis (in Scarsdale). Beautiful “Society” girls get crucified on the ninth hole of the Harrisonville

Golf Club. Evil non-sectarian clergymen cause young people to commit

suicide. International satanic 'combines' kidnap young women at

wedding rehearsals in Episcopal churches.

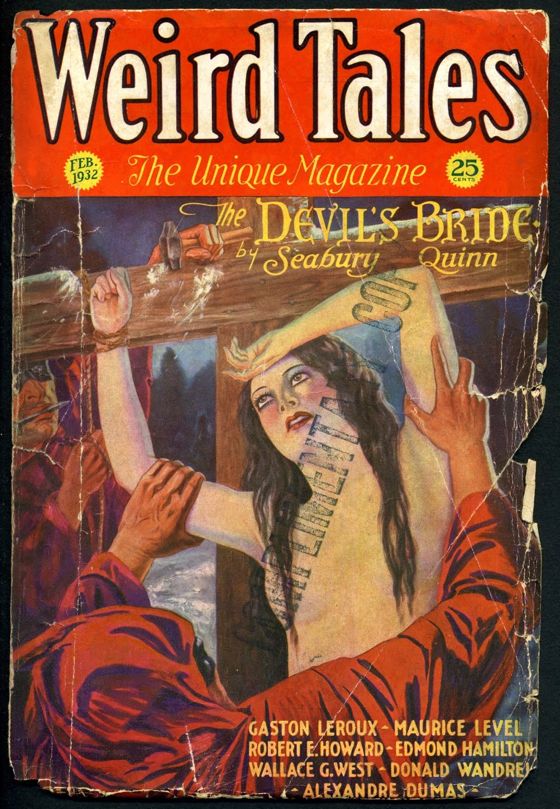

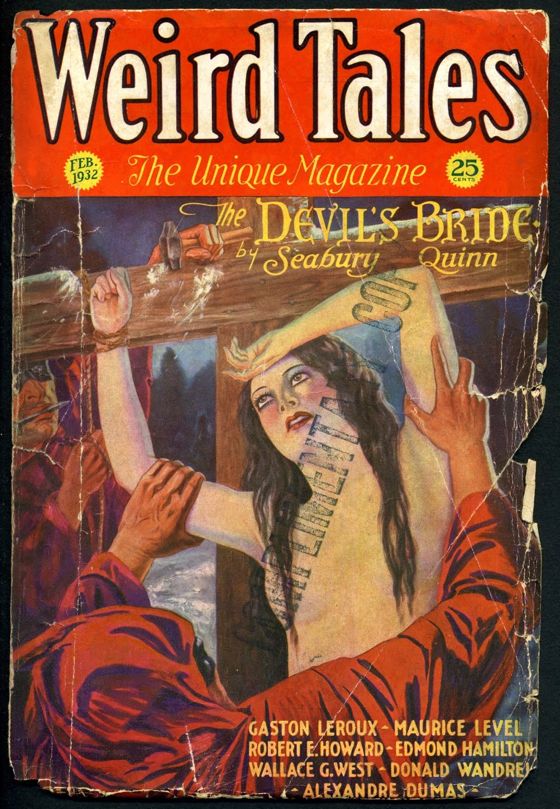

That particular kidnapping,

by the way, is one of Seabury Quinn's great set-pieces. It takes place

in the 1932 novella entitled The Devil's Bride; and in it the heroine

is abducted right under the nose of Doctor Bentley, the Rector of St.

Chrysostom's, during the Friday afternoon rehearsal for her wedding the

following day. Quinn, like his much more mainstream contemporary James

Gould Cozzens, 'gets' the situation he is describing. When I came

across that particular story, I was simply stunned. Had Seabury Quinn

been sitting in the back of the church during the

every-Friday-afternoon-at-five rehearsal that is still a characteristic

of church life in this country?

Two great stories involving Jules de Grandin — both available in

paperback anthologies of Quinn's work published in the mid-1970s — are

the 1928 “Restless Souls” and the 1930 “The Brain Thief”. In “Restless

Souls” de Grandin administers a mercy-killing to a young woman who has

become a vampire and who is actually and really in (human) love with a

predatory vampire. Our hero makes it possible for the woman to bring

her love for this (creep) to fruition, simply out of compassion for her

obsessive state. Then he takes a further step of compassion, and it is

unaffectedly touching. It is also unexpected.

In “The Brain Thief” an Asian mentalist succeeds in hypnotizing two

young marrieds in Harrisonville into deserting their respective (good)

spouses,;carrying on an outrageous public affair, scandalizing the

whole town; and then marrying one another, and having children by one

another — only to be malignantly snapped out of it by the mentalist,

thereby triggering their suicides from guilt and shame. For the period

in which it was written, “The Brain Thief” is shocking. Even for now,

it is upsetting. Although the villain is taken care of, the story

ends on a note of inevitable tragedy that can sear itself into you.

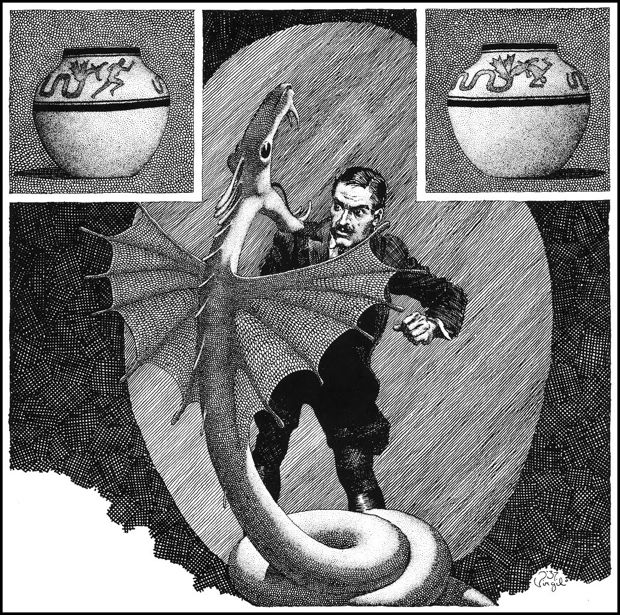

If you like horror fiction of any voltage, from Baring-Gould (low

voltage) to Clive Barker (high voltage), you will like the Jules de

Grandin stories of Seabury Quinn. You will also like the illustrations

of Virgil Finlay, who illustrated quite a few of them. You may also

appreciate the broadly tolerant WASP context of many of the stories,

as well the diverse undersides of that world, which are constantly

surfacing, as in “The Brain Thief”, and causing carnage.

Finally, can I say a word about Jules de Grandin's religion? It

figures in the stories. You can't escape it. And it is fairly

wonderful, and . . . contemporary. In a gruesome little tale from 1927

entitled “The Curse of Everard Maundy”, the named villain is a

non-sectarian revivalist, a thorough squid as it turns out. When Jules

de Grandin informs Dr. Trowbridge that they will be attending one of

Maundy's services, Dr. Trowbridge comments, “But aren't you a Catholic,

de Grandin?”

This is the great one's reply:

“Who can say? My father was a Huguenot of the Huguenots; a several

times great-grand-sire of his cut his way to freedom through the Paris

streets on the fateful night of August 24, 1572. My mother was

convent-bred, and as pious as anyone with a sense of humor and the gift

of thinking for herself could well be. One of my uncles — he for whom

I was named — was like a blood brother to Darwin the magnificent, and

Huxley the scarcely less magnificent, also.

“Me, I am” — he elevated his eyebrows and shoulders at once and pursed

his lips comically — “what should a man with such a heritage be, my

friend?”

Now that is just simply too good. Evocations of John Calvin, Audrey Hepburn, and

Aldous Huxley: for what more could you ask?

Here is to Jules de Grandin, and to his great creator, and to his

excellent illustrator. Requiescent in pace.