Hundreds of years from now, when historians look back at the intellectual life of the 20th Century, I think they will be struck by two extraordinary, almost inconceivable delusions, one aesthetic and one political.

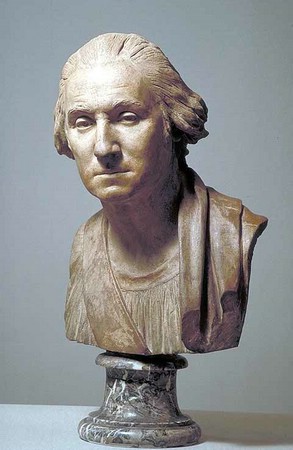

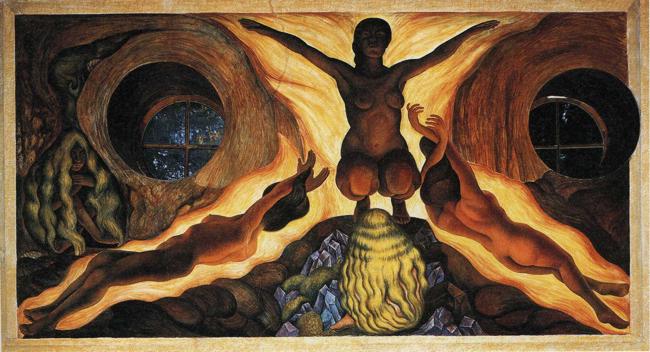

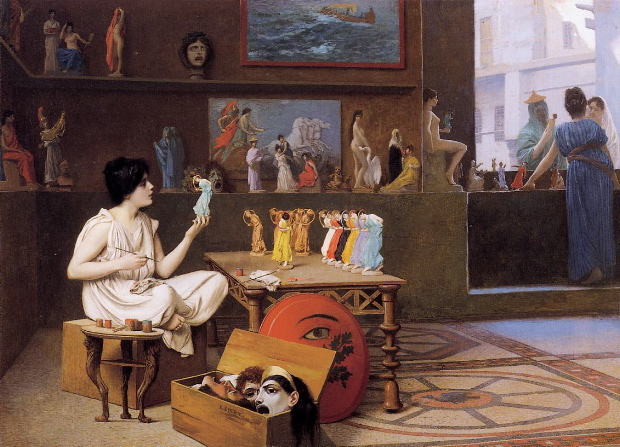

In this post I'll discuss the aesthetic delusion, which involved the violent reaction against the art of the Victorian age. The disillusionment with the European political structure brought on by the madness of WWI created a sense among intellectuals that all aspects of the 19th century world had been invalidated at a stroke. Modernism in the arts arose as a response to this, attended by great glamor and energy. It was primarily reactionary — the new forms it embraced rarely had value in themselves . . . their juice derived from the simple fact that they were not Victorian, were anti-Victorian.

Most of what had made art valuable as a cultural force — as an example of virtuosity, of discipline, of social community, of faith — was simply jettisoned. In their place was substituted “attitude”, the attitude of rebellion. The fine arts of the 20th Century instantly became irrelevant to the popular mind, finding a home in the esteem of an increasingly hermetic elite, dependent on institutional support for their survival.

The irony of this was little appreciated. The academic art of the 19th Century, against which the modernists rebelled, had depended on official endorsement, but also on the approval of a wide and diverse public. The “anti-academic” art of the new, permanent “avant-garde” had no life at all apart from the patronage of museums, institutes of “higher learning” and a gallery establishment catering to the very wealthy.

The old functions of art continued to be performed in areas outside the control of these elites, in the arts of film and popular music, for example — which is why film and popular music became the most exciting and dynamic art forms of the 20th century, even as what were formerly seen as “the fine arts” went on enacting their increasingly tiresome rituals of negation, carried to absurd extremes. Painting, we would eventually be told, was about nothing but paint.

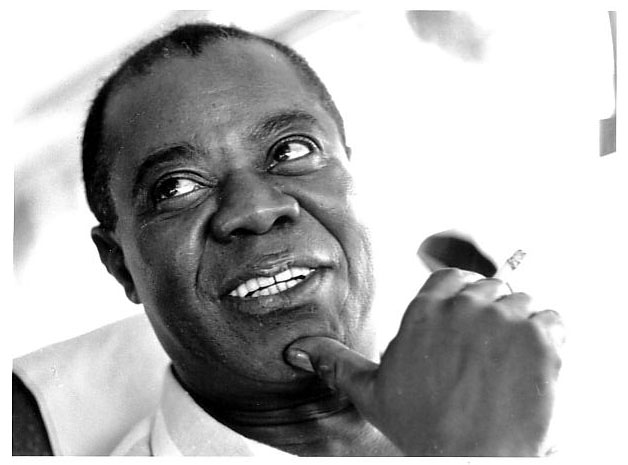

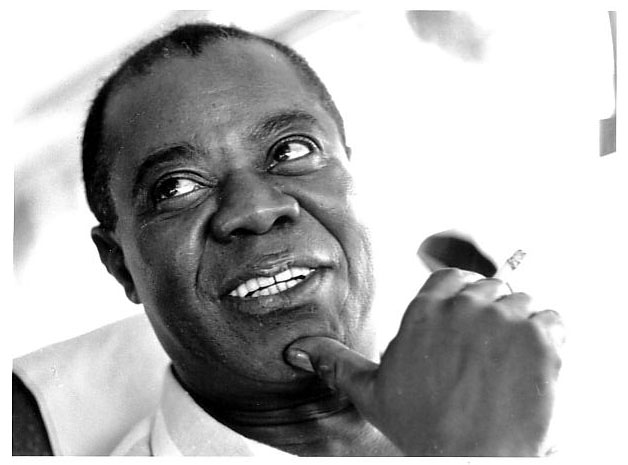

The establishment which once endorsed Victorian academic art, and by extension all traditional art, had become repulsive in the 20th Century. Those who sought to replace this art with “modern forms” became romantic. These labels acted as blinders, almost as blindfolds, until it became impossible to see that the reactionary gestures of the modernists had little content beyond the gestural, while those who toiled away in discredited or unsanctioned forms (like Mr. Armstrong, above) were creating the truly great, valuable and enduring art of their time.

In an upcoming post I'll have a look at the seminal political delusion of the 20th Century.