Truth Escaping From the Well, 1898, an allegory in support of Dreyfus.

Truth Escaping From the Well, 1898, an allegory in support of Dreyfus.

Symphony In White No. 1

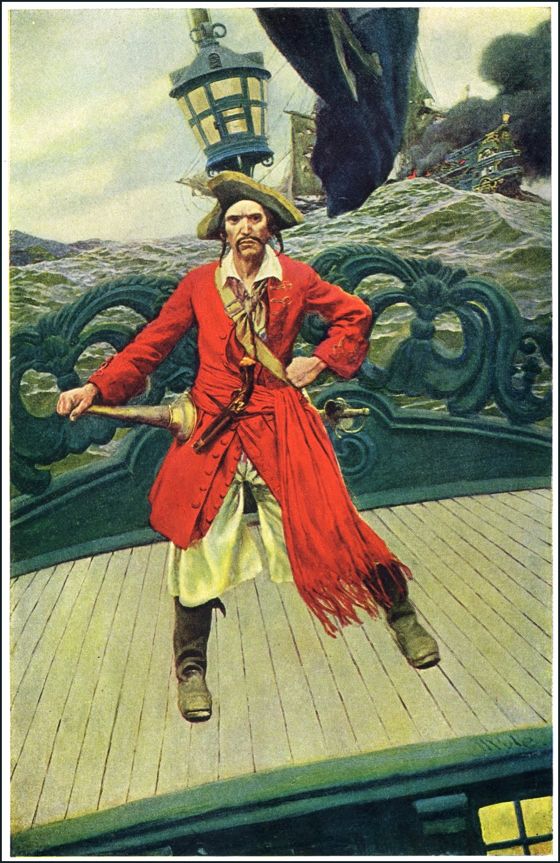

“Captain Kidd”, from Howard Pyle's Book Of Pirates.

As kids, Joel and Ethan Coen were obsessed with the works of Howard Pyle and his disciple N. C. Wyeth. They were especially fond of the image above, one of those collected, after Pyle's death, in Howard Pyle's Book Of Pirates. They reconstructed a version of the scene in True Grit — in the cabin where Rooster and Mattie are holding the two captured outlaws.

Pyle was a very great artist, and once highly regarded — Vincent van Gogh told his brother that Pyle's work struck him dumb with admiration. He is not as well regarded today — there are no first-class collections of his work in print — but Victorian academic art continues to inform the great visual artists of the cinema, if only at second or third hand. John Ford would have known Pyle's work well, and if the look of True Grit reminds you of the look of a Ford film, it's in part because Ford and the Coens all learned from the dynamic and dramatic compositions of Pyle and his followers, so powerfully “cinematic” in their effects.

If you are, like me, a fanatical admirer of the much mocked and despised 19th-Century academic painter William Bouguereau, you will want to save your pennies for an extraordinary new work devoted to his art, the Catalog Raisonné On William Bouguereau. It's a massive, and very expensive, two-volume biography and catalog raisonné listing and reproducing all his known paintings. Beautifully printed and bound, with hundreds and hundreds of mostly excellent color reproductions, it will take your breath away.

Devoting this much attention to Bouguereau is almost an act of defiance — a way of asserting his importance in the face of decades of scholarly scorn. His popularity has never needed defending, despite the unwillingness of museums to show his work throughout most of the 20th Century. People have always loved his images. Now, prices for his paintings are escalating at an astonishing rate, and the Musée d'Orsay has recently acquired five new works by him, including L'Assault, pictured above, and Compassion, pictured below, which will hang on permanent display with the two the museum already owned.

I pre-ordered a copy of the Catalog ages ago, at a greatly reduced price, and waited patiently as its deadline for publication was constantly pushed back. I confess there were times when I wondered if the project was all a fantasy. But the set arrived a couple of days ago, and it was worth the wait.

Today, post-publication, the set will cost you $350 — from the Art Renewal Center, which co-sponsored the project — and many months of your time to browse and read. (If the price is too daunting, the Art Renewal Center plans to donate copies to libraries, so you'll be able to get your hands on one for free eventually.) The Catalog may spark a reappraisal of Bouguereau's work in the art world, or not — that hardly matters. It will certainly expose many new people to the work, and promote a consequent suspicion of the judgments of the art world.

Bouguereau's visions are meticulously conceived and executed, and often quite mad. They are endlessly astonishing and entertaining, and sometimes moving. They have a regard for sentiment and a connection to popular taste that most painting lost in the 20th Century, but will reclaim someday. Bouguereau is not about the past — he's about the future. Get to know his work and you'll see why. Virtuosity combined with pleasure and surprise never goes out of style, at least not for too long.

Jean Béraud's portrait of remorse — but for what? Thus did the Victorians tease and titillate . . .

Wait — come back!

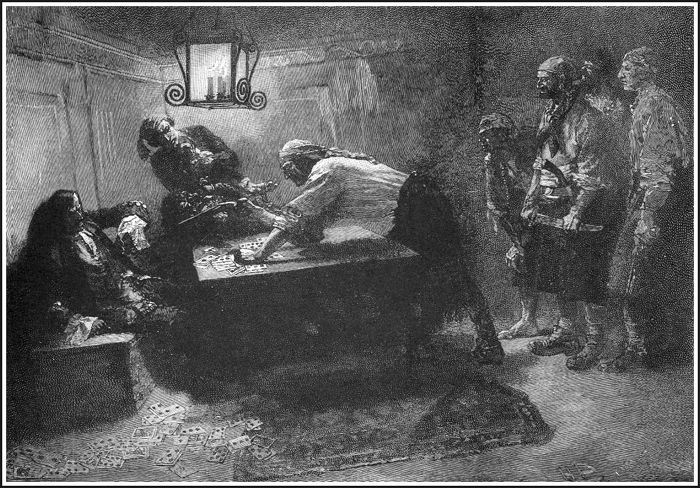

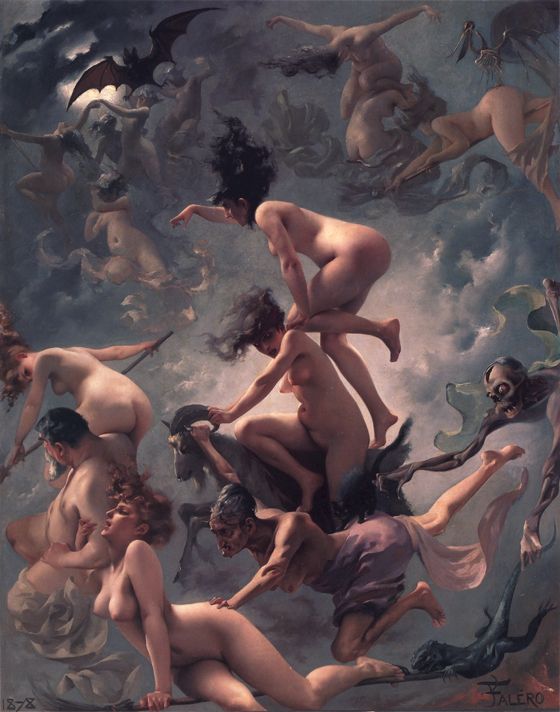

At first glance, this looks like a painting by Bourguereau gone stark raving mad, or something Frank Frazetta might have done if he'd been a Victorian academic painter. In fact, it's a work from 1878 by Luis Ricardo Falero. Falero did a lot of supernatural-themed paintings with voluptuous nudes, but from what I've seen, this is his masterpiece.

The depth of the image, and the smarmy but delightful eroticism of the scene, are wonderful.

[With thanks to Boing Boing.]

Work Interrupted

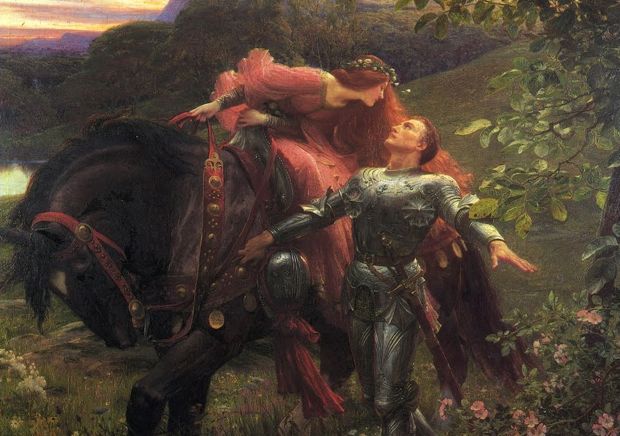

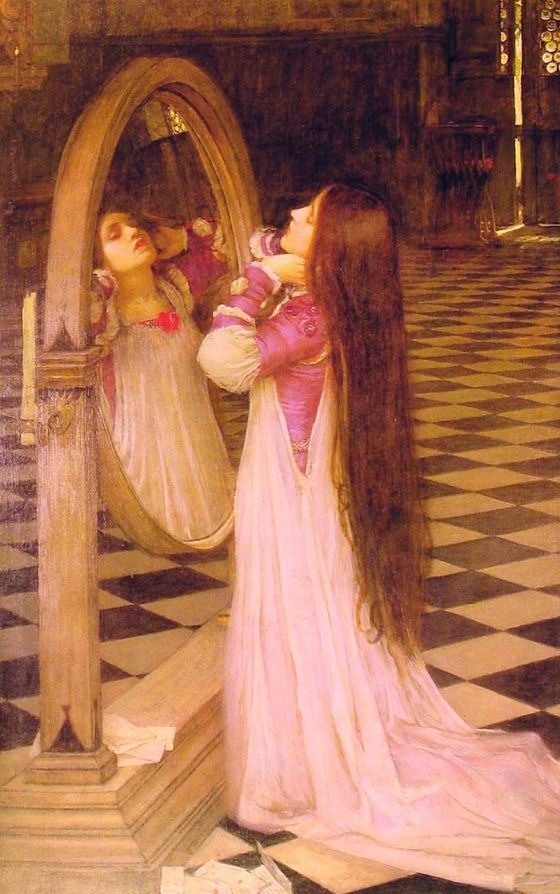

I met a lady in the meads

Full beautiful, a faery’s child;

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long;

For sideways would she lean, and sing

A faery’s song.

Lines by John Keats, image by Frank Dicksee.

Percy Bysshe Shelley howls at the moon:

Art thou pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless

Among the stars that have a different birth,

And ever changing, like a joyless eye

That finds no object worth its constancy?

[Image by John William Waterhouse.]

Here's something you don't run across every day . . .

[Image by Edmund Blair Leighton from the gallant Golden Age Comic Book Stories.]

Completed between 1883 and 1885, this painting is known as The Sporting Ladies and also as The Circus Lover from a series called Women Of Paris.

As with several images of the circus by Tissot, and many other works as well, the painter has created a number of distinct spaces that draw us into the scene progressively — the space occupied by the gentleman leaning in towards the ladies, with the unseen part of his figure seeming to occupy our, the viewers’ space, into which the central female is peering, the space of the seated ladies, the space of the circus ring, and the space of the background seats.

The space of the circus ring is further articulated into the aerial space of the trapeze artists and the space of the clown in the sawdust and there is, as a kind of punctuation, a glimpse in the distant background of a lighted foyer opening on to the highest rung of seats.

The elegant calculation of the composition makes for a very dynamic and seductive image.

Jean Béraud left us the most charming records of the boulevards and cafés of Paris during the Belle Époque. The Impressionists often treated the same subjects, but their emphasis on the surfaces of their canvases, on effects of light and color, took precedence over documentary concerns. Béraud wanted us to know how it felt to physically inhabit the places he painted. Like all academic painters, he concentrated on the drama of space, as a way of drawing us imaginatively into his images.

The painting above depicts La Pâtisserie Gloppe on the Champs Élysées in 1889. Béraud evokes the magical use of mirrors in the shop's interior, the behavior of its patrons, the bourgeois ordinariness of the scene. It is rooted in the here and now, which has become the there and then, and so oddly poignant, in a way the Impressionists rarely are. Béraud recedes into his work, creating a space for us to enter this bygone moment of a bygone age.

The image has something of the authority of a photograph and something of the intense subjectivity of the artist's desire to record just what he saw, just what he thought we might have seen if we had been with him that day in the shop, and no more.

He has created a profoundly democratic work of art, radically out of step with the neo-Romantic egocentricity of the 20th-Century modernist.

Hundreds of years from now, when historians look back at the intellectual life of the 20th Century, I think they will be struck by two extraordinary, almost inconceivable delusions, one aesthetic and one political.

In this post I'll discuss the aesthetic delusion, which involved the violent reaction against the art of the Victorian age. The disillusionment with the European political structure brought on by the madness of WWI created a sense among intellectuals that all aspects of the 19th century world had been invalidated at a stroke. Modernism in the arts arose as a response to this, attended by great glamor and energy. It was primarily reactionary — the new forms it embraced rarely had value in themselves . . . their juice derived from the simple fact that they were not Victorian, were anti-Victorian.

Most of what had made art valuable as a cultural force — as an example of virtuosity, of discipline, of social community, of faith — was simply jettisoned. In their place was substituted “attitude”, the attitude of rebellion. The fine arts of the 20th Century instantly became irrelevant to the popular mind, finding a home in the esteem of an increasingly hermetic elite, dependent on institutional support for their survival.

The irony of this was little appreciated. The academic art of the 19th Century, against which the modernists rebelled, had depended on official endorsement, but also on the approval of a wide and diverse public. The “anti-academic” art of the new, permanent “avant-garde” had no life at all apart from the patronage of museums, institutes of “higher learning” and a gallery establishment catering to the very wealthy.

The old functions of art continued to be performed in areas outside the control of these elites, in the arts of film and popular music, for example — which is why film and popular music became the most exciting and dynamic art forms of the 20th century, even as what were formerly seen as “the fine arts” went on enacting their increasingly tiresome rituals of negation, carried to absurd extremes. Painting, we would eventually be told, was about nothing but paint.

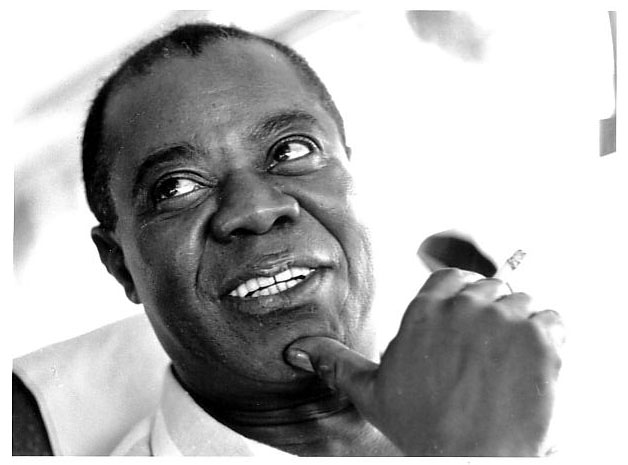

The establishment which once endorsed Victorian academic art, and by extension all traditional art, had become repulsive in the 20th Century. Those who sought to replace this art with “modern forms” became romantic. These labels acted as blinders, almost as blindfolds, until it became impossible to see that the reactionary gestures of the modernists had little content beyond the gestural, while those who toiled away in discredited or unsanctioned forms (like Mr. Armstrong, above) were creating the truly great, valuable and enduring art of their time.

In an upcoming post I'll have a look at the seminal political delusion of the 20th Century.