In the mythology of modern art history the realist painters of the

Victorian era fought a losing battle with the photograph and eventually

capitulated to the dominant aesthetic of 20th-Century art, with its

irresistible (and progressive) trend towards a greater and greater

abstraction, abandoning both pictorial realism and almost all narrative

ambitions.

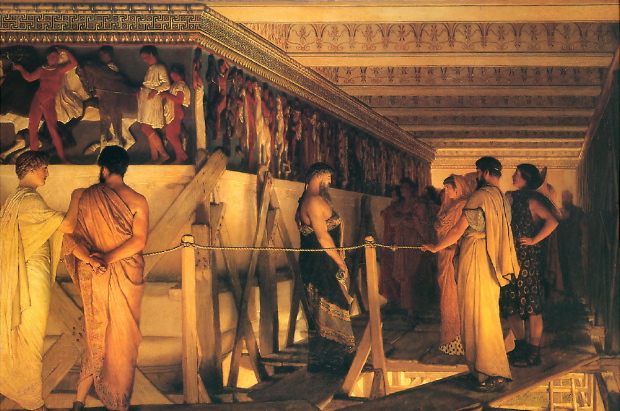

In fact, however, realist painters of the Victoria era conducted an

exciting and productive dialogue with the photograph, incorporating its

apparent authority but also, at the same time, extending its range of

representation beyond the technical limits of the 19th-Century camera.

Academic art surrendered not to the abstractions of the 20th-Century

painter but to the great artists of the early cinema, who assumed the

narrative and representational ambitions of academic art in a medium

which had, at least as far a popular taste went, better resources for

realizing those ambitions. You could almost say that the academic art

of the 19th-Century was born again, gloriously, in a new medium, which

it deeply influenced.

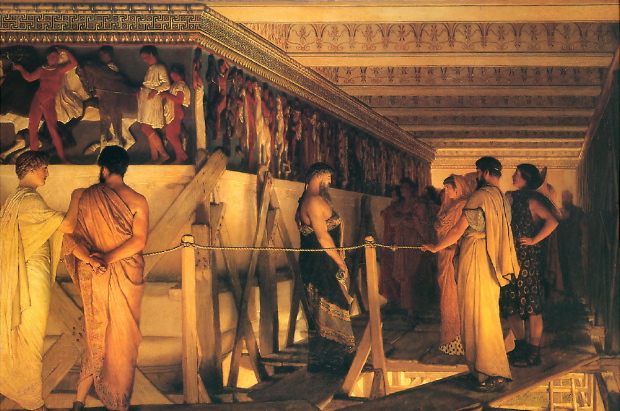

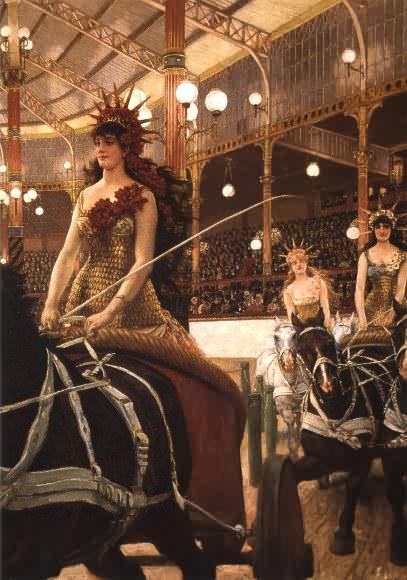

Academic art taught movies how to orchestrate photo-realistic elements

into theatrical forms, using lighting, framing and the placement of

figures in space to create a hyper-realistic illusion that had the

coherence of actual visual experience even when departing from it in

fabulous ways. Because film could capture motion, and thus emphasize

the plasticity of space far more expressively than the easel-painter,

it rendered the academic easel-painter’s art passé. It was motion and

the greater illusion of spatial depth it allowed which lost academic

art its popular following.

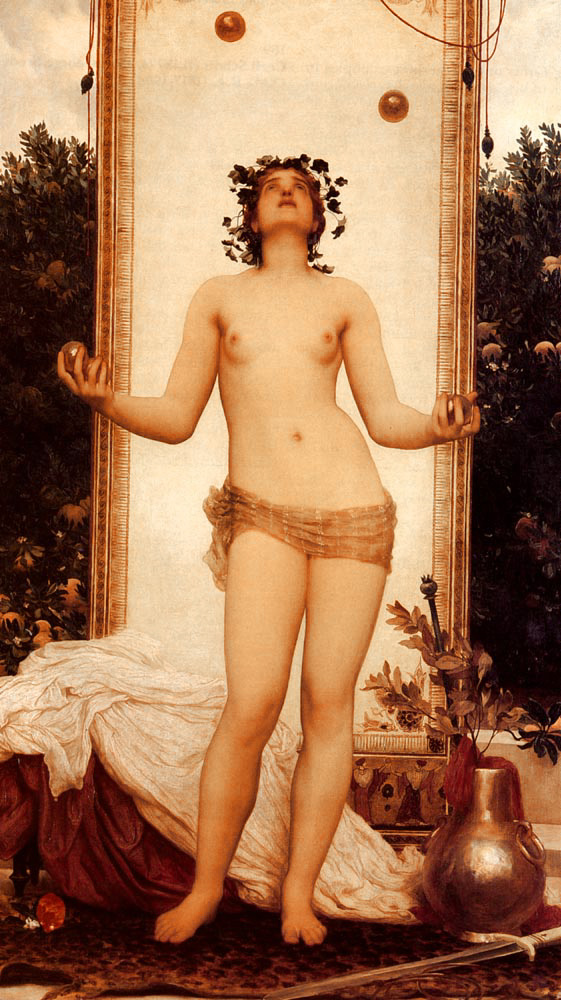

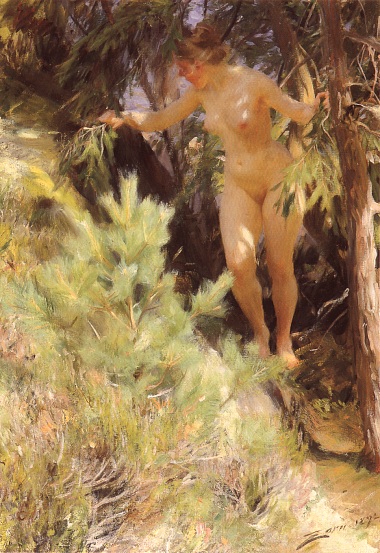

But much more than that was lost, especially in the realm of color. Up

until very recent times, color film stocks couldn’t begin to reproduce

the range of lighting conditions which the Victorian realist painters

gloried in. By marrying, through draftsmanship, an almost photographic

realism with an über-photographic sensitivity to color and light, the

Victorian painters anticipated cinematic effects which remain difficult

to achieve even today.

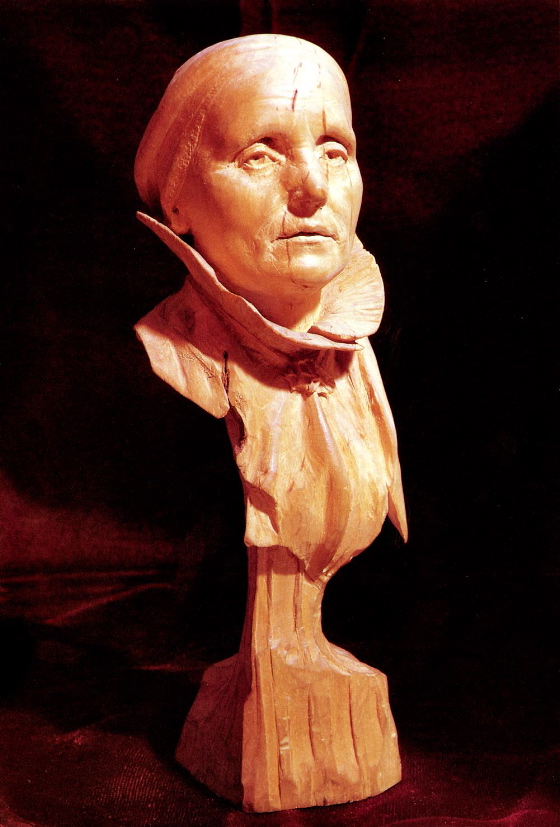

The attempt to devalue the work of Victorian painters, seeing them as

obstinate blocks to the steady progress of art, was a strategic ploy on

the part of 20th-Century modernist painters and their apologists in the

academy and the marketplace. Engaged in a project which would divorce

art from popular taste and arrive at an aesthetic dead end before the

end of the 20th century, they posited a straw man in the person of the

reactionary academic practitioner which lent their own schools an

undeserved glamor and prestige — even as the academic practitioner was

informing and inspiring the great new popular art form of the movies.

But the intellectual disgrace of the Victorian painters also helped

impoverish cinema, because, after the first glorious blossoming of the

art in the silent era, filmmakers forgot academic painting. To get

back in touch with its lessons, they had to get back in touch with the

masters of the silent era, like Griffith, Vidor, Murnau and Ford, for

whom Victorian academic painting was a living form and a direct

inspiration of their techniques. The filmmakers who followed them had

to engage Victorian academic art at one remove, and thus lost touch

with the very forms which had inspired and instructed the original

pioneers of cinema.

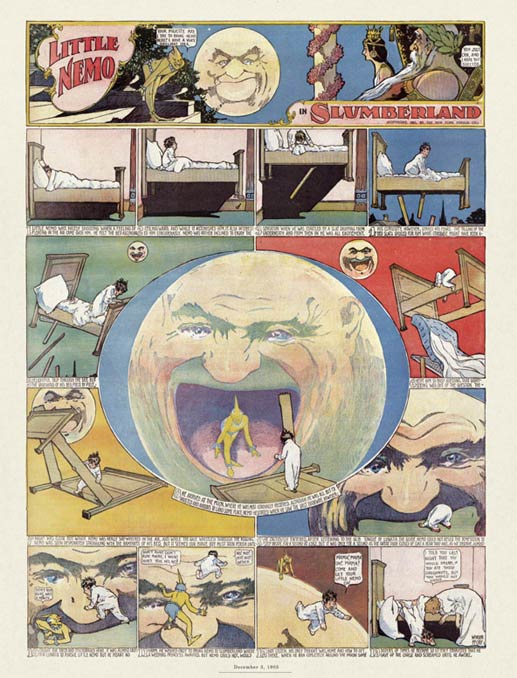

The propaganda of the modernist painters, understandable from their

point of view, resulted in a great loss to the visual culture of the

20th-Century. It couldn’t obliterate the glories of Victorian academic

painting, which survived, transformed, in movies and in popular

illustration (through the work of artists like N. C. Wyeth and Norman

Rockwell.) But it distorted the intellectual appreciation of a visual

tradition which might have been of great use to artists, film artists

especially, if they hadn’t been shamed into despising it on principle.

I would argue that a new appreciation of Victorian realist painting has

the power to recharge the art of cinema in our time — quite apart from

the pleasures to be gained by directly encountering a vital and

ravishing visual tradition.