I

was leery of visiting Cabo San Lucas, reputed to be an outpost of

Orange County, but El Arco is there, the rock arch (above) that marks the

bottom of the Baja California peninsula, and it seemed unthinkable to

have driven most of the length of the peninsula and not visit its

terminal point, where the waters of the Pacific meet with the waters of

the Mar de Cortés.

We decided to make a beeline for land's end, see the cape, and head

straight back to La Paz. This turned out to be easier than

expected because there's a new road to Cabo San Lucas from La Paz

which runs down the Pacific side of the peninsula. (Mexico 1,

formerly the only paved route from La Paz to the cape, runs down the eastern shore of the peninsula and is a bit longer.)

The new road on the Pacific side is in superb shape, allowing for faster speeds than

normal, and we made it to Cabo San Lucas well before noon. The

town of Cabo San Lucas still has some charm, but it's ringed about by

hideous condo compounds — enclaves for people who want the views but

don't want to live among Mexicans, in anything resembling Mexican

culture. In forty years the whole of Baja California will

probably be encrusted with these compounds, as the Pacific coast above

Ensenada already is. Go see it now, before the

yuppie stain grows insupportable.

The tip of the cape can only be visited by sea, unless you're an expert

rock climber. We rented places in one of the glass-bottom

superpangas that take tourists out for a look. Fortunately the

other passengers were one large extended Mexican family, cheerful and

friendly and good company.

As we motored out of the harbor we were greeted by the strange and

nauseating sight of huge party boats filled with tourists drinking and

listening to bad pop music from live bands blaring their sounds out

over huge amplifiers. “We're having an experience — we're having

fun now!” was the message. Not. “We might as well be in Las

Vegas!” was more like it.

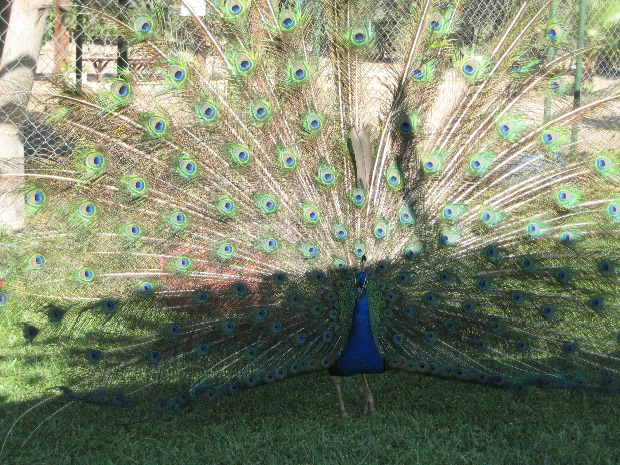

El Arco looks as though it might have been designed for dramatic effect

and beauty by some 19-Century landscape artist like Frederick Law

Olmstead. It's a most appropriate and theatrical punctuation mark

at the end of the great peninsula. Just beyond it you can

actually see the light green water of the Mar de Cortés mix with the deeper

blue of the Pacific.

The captain of our panga had his wife and kids and father on board —

his oldest son took the helm on the ride back to the docks. His

father beamed at him and made sure we all saw how well he was doing.

We decided not to tarry in Cabo San Lucas but headed back

towards La Paz and stopped about halfway there at Todos Santos for

lunch. Todos Santos is a lovely little town that's become

something of an artists' colony. We looked forward to visiting

the galleries there, but they were all closed, because we came on

a Sunday. You would think that Sunday would be the one day of the

week most likely to bring tourists into the galleries, but there is

obviously a higher law at work here — the Lord's day, and the day of

rest, trumping commercial concerns.

We did have a fine lunch at the Hotel California, a charming place

that

is often visited by Americans on the mistaken assumption that it has

some connection with the Eagles' song. Harry had the Mexican

equivalent of surf 'n' turf — a plate of shrimp and carne asada tacos.

We got back to La Paz before dark, in time for drinks at sunset on the terrace of the Hotel Perla.

We were happy we'd visited Cabo San Lucas,

and land's end — even happier that we didn't have to spend the night

there.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]