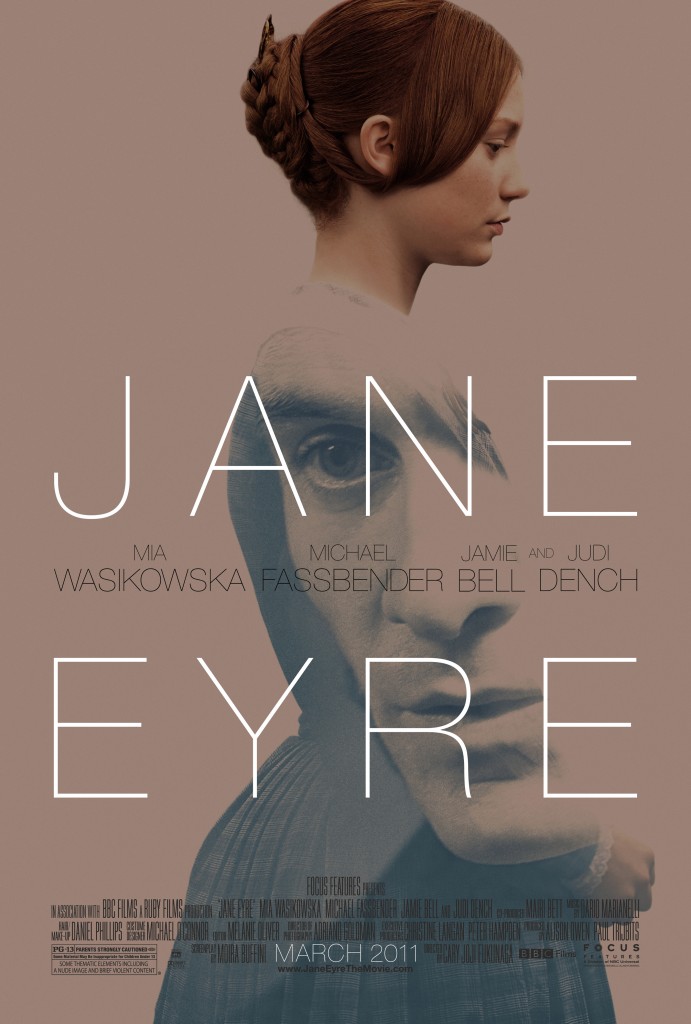

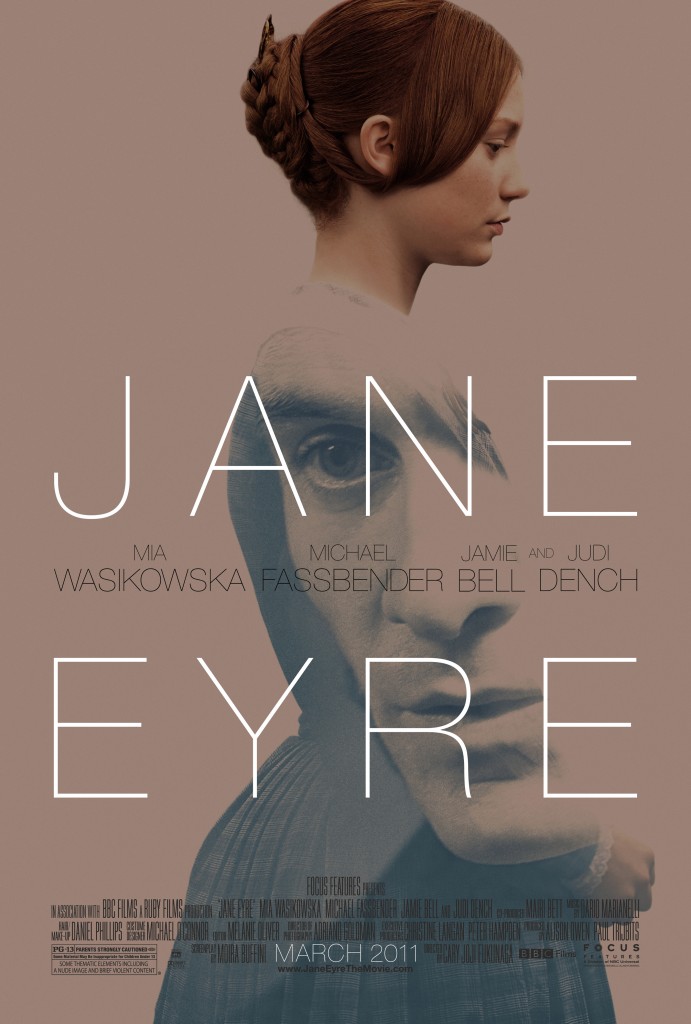

A few nights ago I watched Cary Fukunaga’s 2011 adaptation of Jane Eyre and I can’t stop thinking about it. It’s not a perfect film but it’s brilliant in many ways, and a number of them derive from the script by Moira Buffini.

As my friend Ron Salvatore has noted, it must have been very tempting to portray Jane as a modern-day feminist trapped in a corset, but any attempt to do that, to associate her independence with any form of modern ideology, would have robbed Jane of her prime virtue — the fact that she is a woman who figures things out for herself.

In fact, Charlotte Bronte and Jane base their claims for female equality on an inner faith in themselves as individuals, and justify that faith on religious grounds. It’s easy to forget that the true roots of modern feminism lie in the Protestant Reformation, and its insistence that each soul, male or female, is responsible for its own salvation. (Not responsible, it must be noted, for earning its own salvation, since in core Protestant theology salvation can’t be earned, but responsible for accepting the salvation offered as a gift by God.)

This doctrine led directly to the Protestant disapproval of arranged marriages, on the grounds that it was an individual woman’s responsibility to marry a godly man, even in defiance of her family’s wish to the contrary. This caused a social upheaval which is evident in art as early as Shakespeare’s plays, which deal repeatedly with conflicts between fathers and daughters over issues of marriage, with Shakespeare invariably endorsing the rights of the daughters.

Buffini does not shy away from the now utterly uncool religious foundation of feminism. She follows Bronte in the moment when Jane makes her case for equality with Mr. Rochester, as follows:

Am I a machine without feelings? Do you think that because I am poor, obscure, plain and little that I am soulless and heartless? I have as much soul as you and full as much heart. I’m not speaking to you through mortal flesh . . . It’s my spirit that addresses your spirit as if we’d passed through the grave and stood at God’s feet, equal — as we are . . . I am a free human being with an independent will, which I now exert to leave you.

This is Jane speaking from the depth of her being as a person of faith — she believes that her right to equality and independence is a gift from God, just as the signers of the American Declaration Of Independence did.

But, as with those signers, Jane’s equality and independence are things she feels inherently — they constitute a truth which she holds to be self-evident. Who knows how many women of Jane’s time felt the same? Jane’s heroism lies in the fact that she has the courage to speak of it openly, defiantly, without regard for consequences.

And this is the key to the genius of Fukunaga’s film, and to Mia Wasikowska’s exceptionally fine performance as Jane — they show us the mind of Jane at work behind the level gaze, they convince us of her faith in herself and in God.

What they give us, in fact, is a real woman on screen — a woman who exists independent of male desire and male control, a woman who is responsible for her own soul. This is all but unique in modern movies — at least since Rose, old Rose and young Rose, in James Cameron’s Titanic. All the other examples I can think of involve much younger females, Mattie Ross in the Coen brothers’ True Grit, Suzy Bishop in Moonrise Kingdom, Hush Puppy in Beasts Of the Southern Wild.

But Wasikowska’s Jane is a mature woman, and the fierceness of her individuality and will has a decided erotic quality, which works on us as it works on Mr. Rochester. In her bastions of Victorian drapery, she is far more vexing than the half-clothed cartoon women who titillate male vanity in most modern movies. We become convinced that there is a real woman beneath all that drapery, behind all that circumspect locution — and we are reminded how sexy a real woman can be.