VISIONS OF THE JOAN-GIRL

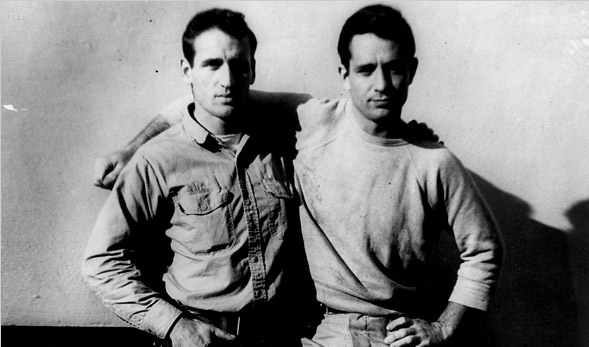

by Paul Zahl

On January 9th, 1951 Jack Kerouac had a vision in St. Patrick's

Cathedral on Fifth Avenue in New York City. He wrote the vision down that night and sent it to Neal Cassady. It was published in 1995 in the Selected Letters 1940 – 1956, edited by

Ann Charters, and is found on pages 281-293.

The letter hit me with a wallop, because it contradicts the reputation

Kerouac has earned for misogyny. The letter is a religious vision concerning women, and also men, which

embodies a catharsis of feeling and rue, on the part of the visionary, for the feelings of contempt that

governed most of Kerouac's treatments of women in his work.

It is made even more worthy of attention by the fact that four months

later, in a letter dated May 22nd,

Kerouac told Cassady to “pay no attention” to what he had written about

women in January. He “regressed”, in other words. And he never quite came back to this universal chord.

In New Testament scholarship — to make an abrupt cross-reference — such textual “taking back” of an earlier testimony suggests the

authenticity of the original statement. In other words, if St. James

in the New Testament writes that he has concerns about some of the

teachings he finds in the letters of St. Paul, this tells the modern

scholar that the “odd” assertions from St. Paul concerning grace and

law really did issue from the man himself. St. James wouldn't

criticize St. Paul, that is, unless there had really been something

there for him to criticize. Similarly, if Jesus enunciates something

very radical, such as “My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?”

within the context of a work that wants to make him All-Glowing and

Tom-Terrific, then the fact that this saying of Jesus has not been

deleted means that it was so strong in the memory of witnesses that

later interpreters could not have cut it if they tried.

Similarly, Kerouac on January 9th, 1951 experienced something very

real, for him. The fact that he becomes uncomfortable with it in on

May 22nd strengthens its veracity as a real dream, a real “touching of

the foundations of his soul” (his words).

This letter, which is quite sublime in its writing in my opinion, is

worth quoting at length. I will do so with some interstitial personal commentary. A short summing-up, of this loaded,

surprising material from the “Beat” pioneer, will follow. There are two further things to mention, before you read Kerouac's

letter.

It is a vision, his letter. It bursts over and upon him, and he is not

expecting it. It is completely accidental, in fact, since he ducked

into St. Patrick's only to find a place to take shelter from the

busy-ness of Midtown. He did not know he would get caught up in a

religious service, or novena. The letter recounts his vision, linked to

a statue he sees and studies and thinks about. It is a vision which

observes; and in observing one particular woman, seated in a pew in

front of him, he begins to think about his wife, and then about his

view of women in general, and finally, about men, in general.

Secondly, Kerouac's letter is emotional. Everything begins to happen

when he starts to cry. He is not able to explain his tears. Yet he

moves thereby beyond the “aesthetic” (his word) to the sub-rational.

That's when the “work” of the vision takes place. This is to say that

the “aesthetic” carries him to the “emotional”, and it is an awesome

thing.

Now, dear Reader, if you are willing and ready, Behold:

TO NEAL CASSADY

Jan. 9, 1951

(Richmond Hill, N.Y.)

Dear Neal,

To continue. A new experience has touched the foundation of my soul since I wrote you the last words last night . . .

Kerouac sets the scene:

I came into the Cathedral not only to get out of the bitter cold, but because, moments before, I had stood in Grand Central Station looking around with a futile sorrow for a place to sit and think. All there was — marble floor, rushing crowds, dime lockers, bleak seatless spaces and bright vast corners. What a thing men have let themselves in for, in this New York!

I hurried out in the cold and cut up 5th Avenue, past the (yes) Yale Club and past Harcourt Brace (yes) and swore and cursed; and cut right by the Doubleday Book store without deigning to go in and see if they had my book [i.e., his first published novel, The Town and the City] on

display . . .

As you know, St. Patrick's is a Gothic cathedral, copied after Rheims or Chartres or whichever, with a rectory in the back, and a big department store across the street on 50th street. I . . . ducked . . . into the side entrance of the church.

Now our hero must begin to “let go” of his “renegade Catholic” baggage,

and also his heavy personal baggage:

At first I sneered as all the commonplace “renegade Catholic” thoughts came to me in regimental order but soon I was lost in real sweet contemplation of what was going on . . .

I put away all my worries of where to get a job, how to get to California next month, what to do about my poor wife whom I had been torturing in my subtle way lately, and just merely sat thinking in church . . .

Kerouac suddenly invokes Dietrich Buxtehude!

. . . so that you see . . . my first thoughts were superficial, or let's

just say “aesthetic.”

Then something happens:

Frankly, Neal, I don't know when it happened; when it was I began crying . . .

It is as if the writer's ears now become opened, together with his eyes. He begins to take in what is actually going on around him.

A tall athletic young priest was cutting up to make a sermon; simultaneously I noted how much the crowd had thickened; and before I knew it I was in the middle of a fullblown church service. Since I was in the church utterly given over to pure meditation I obediently kneeled, or stood, or sat at the young priest's behest and followed everyone else in so doing. He made several cryptic remarks evidently having to do with the novena everyone was on, and then began a sermon.

Note that Kerouac has the reaction that many visitors to a church

service have when the parish “announcements” are being made. He describes them as “cryptic”. And so they are! (I have always tried

to teach young ministers to make as few announcements as possible in

church. Announcements disenfranchise visitors and give the impression of the

church membership being a kind of club, with “cryptic” sharings. In

most parishes, however, announcements grow, and Grow, and GROW. For my

money, they are a sign of fading vision.)

The priest now begins to speak. At first Kerouac misunderstands what

is being said.

He began talking about how “every ambitious woman wants to see her child become successful in industry, in a profession, in some constructive field.” I slapped the side of my head in despair; for by this time my meditations had carried me far from this modern competitive world into thought of a simple and medieval character. I almost sneered. Then I noticed he was starting out this way for greater punch, because then he said, “What were the thoughts of the Virgin Mother on that first Christmas night with regard to her little son? For she knew, only poverty, humiliation and suffering could save him and she knew he was come for strange reasons into the world.”

And from there on this fine young priest made a beautiful sermon about the advantages of humility and piety in the invisible world that will surmount the pride and decadence of the visible. I agreed with him. I almost applauded . . .

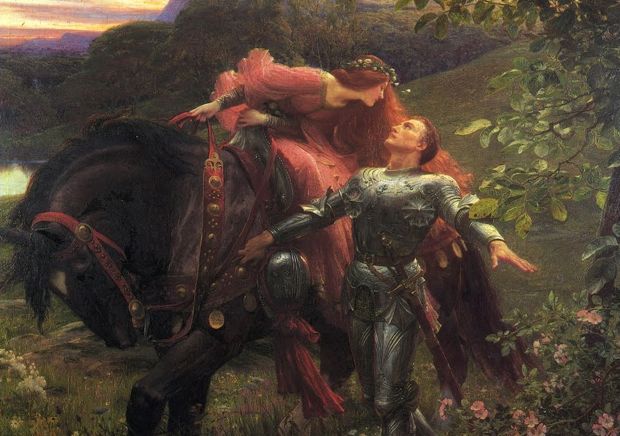

At this point Kerouac starts to think about the Virgin Mary. His

attention is caught by a newly dedicated and consecrated statue in the

Cathedral, of the Virgin Mary with her dead son — the pieta, in other words.

And now I must tell you of the Virgin Mary . . . I was just staring at

what I think was a brand new statue of the Virgin Mary holding her Son in her arms after the

crucifixion . . .

I was amazed to see so many young girls, shopgirls, kneeling around it at the white rail. I couldn't believe my eyes when saw first one, then another, then all of them reach out, touch the statue, touch the red flowers, and bow their heads . . .

Kerouac now associates to his wife. He begins to think concretely

about his most personal relationship, and his role in it. This is where, in my opinion, the letter gets really interesting.

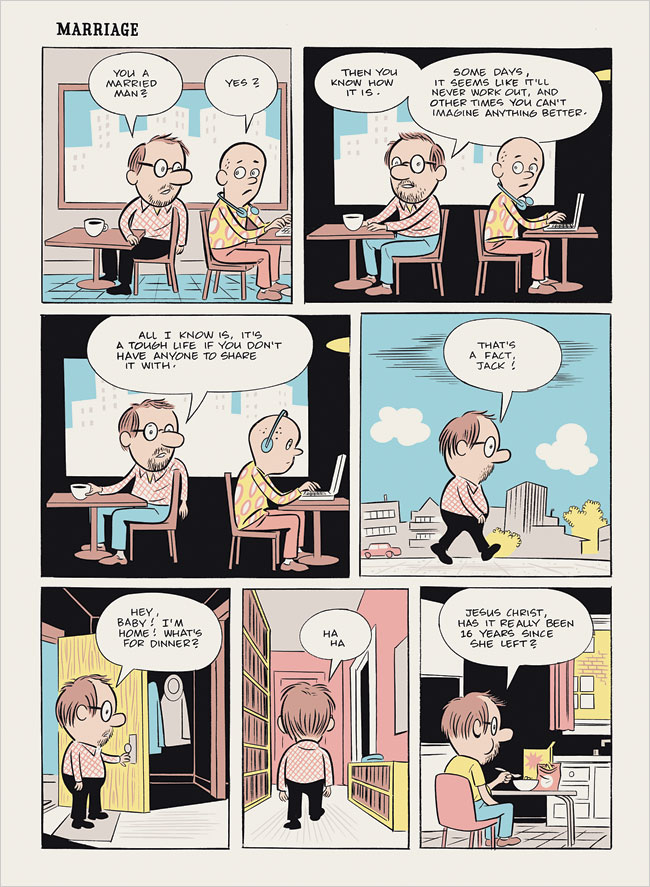

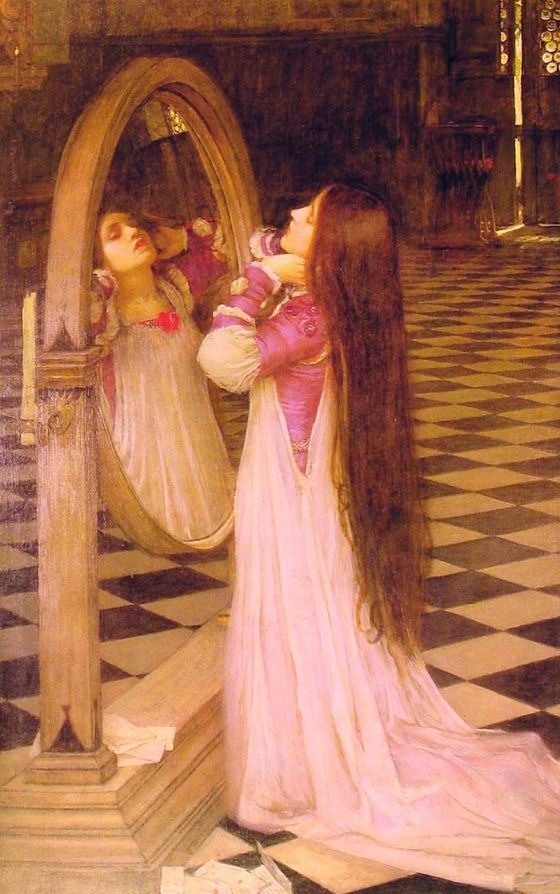

Suddenly I remembered what was wrong between my wife and myself in the past days; she'd said she felt like a “frog” sometimes in the midst of sexual intercourse. I remember it had irritated me . . . Also she never considered herself worth touching when she had a period. Most of all I thought of her — on the impetus of seeing a girl exactly like her [my emphasis] in the pew in front of me — with head bowed, kneeling,

a shawl over her . . . humble head, and I almost cried to think of it.

I saw how all of earthly life, with its gutty sufferings, really passes

like a river through the body of a woman while the man, unknowing of these things and “clean”, just cuts along arrogant. I saw how it is the woman who gives birth, and suffers, and has afterbirths dragged out of her, and navel cords snipped and knotted, and bleeds — while the man boasts of his bloody prowesses . . .

I had even been annoyed at the poor girl lately because she conducted long secret meditations of her own in the bedroom while I “wrote”. “What are you thinking about?” I'd ask slyly. What's going on in her great soul now? I'd ask myself sarcastically. Bah, bah, bah, and all that; as if, and certainly BECAUSE I was a “writer”, she, a mere girl, could not possibly have a soul like mine worthy of hours and of deep contemplation.

Kerouac is recognizing the validity of someone other than himself.

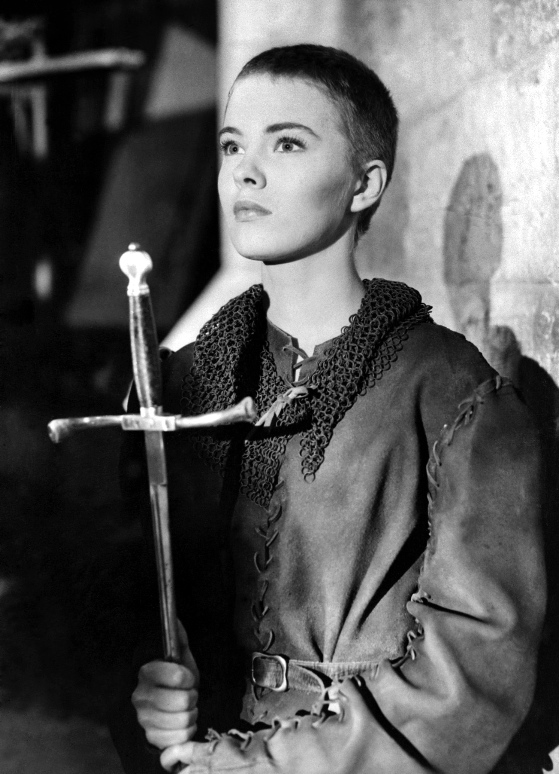

If I had been a little boy of Galilee, and seen the humble women in shawls kneeling at the temple, what would I have thought of Miss Rheingold [i.e., a sexy woman on a billboard advertising beer] . . .? No,

I saw that the girl has a soul . . . For if the burden on earth… could be lifted from one woman, then it may be lifted for another, or to be more precise, the burden is already lifted because the Virgin Mary was [this is a

reference to the Assumption of Our Lady]; just as our sins are expiated by the sacrifice of the great Lord Jesus, without any of us having to be crucified on a cross.

Kerouac now sums up what he has seen, in the form of the “Joan-girl” in

front of him. Joan is the first name of his wife.

No, the tall, humble Joan-girl in front of me, kneeling with bowed head, was a woman who dearly and sincerely prayed for the deliverance of her soul.

Finally, or almost finally, Kerouac considers “men”, and the vain-glory of the male. He writes through the eyes of child, “a little boy of Galilee”:

I further noticed that there were no young men in the church, only old ones; and I knew they were all out making money or being hoodlums with all their might. If I had been a little boy of Galilee . . . what would I have thought of the go-getter in his Brooks Brothers suit hurling himself through a revolving door with that arrogant scowl? I would have thought he was a scribe, or a pharisee, or a thief. If I had been a little boy of Galilee, and seen the old men praying at the Star, what would I have thought of the be-spatted executive hurrying from a conference. I would have thought he was Caesar. This is our world.

A touching word comes out on prayer:

I wished that the church was not only a sanctuary but a refuge for the poor, the humiliated, and the suffering; and I would gladly join in prayer . . . everybody kneeled: I gladly joined in; no other power on this earth could make me gladly kneel, or even stand up. Did I ever tell you about the time I was in the Navy madhouse and the Admiral of the Fleet came in? — I was the only one who didn't stand up, all the other nuts did . . .

Kerouac's letter to Neal Cassady dated January 9th, 1951 concludes with a sort of “coda”, which I find personally touching, and

satisfying. He changed his behavior toward his wife! It didn't last — as our

moments of loving inspiration seldom do — but the vision “became flesh”. For a day, at least, it became flesh. Here is how it went:

In the subway everybody was going home to rest, instead of gathering in the Final Church of Eternal Joy, and I felt bad to see it . . . But when I came home I loved my wife, and kissed her tenderly, as she kissed me . . .

Goodnight, sweet prince.

Jack

From an historical point of view, a “lit-crit” point of view, this

letter is significant because it documents a temporary change of attitude on

the part of this American legend toward women.

Kerouac's attitude toward women is sometimes summed up in his

tossed-off remark, “Pretty girls make graves”. As a poet immersed later in Buddhism, he was desirous, like

Siddhartha, of avoiding re-birth. “Pretty girls”, therefore, he regarded as the pathway to birth, the

birth of babies who were metaphysically understood to be reluctant reincarnations of earlier, failed lives. Kerouac's view of birth, therefore of sex, and therefore of women, was not different in principle from George Harrison's in his mid-career

lyric, “Keep me free from birth”.

But the result in Kerouac's case was an artist's attraction-repulsion

to women that has damaged his critical reception. He is judged harshly for his

suspicion of one half of . . . earthkind.

Here, however, in this discursive 1951 meditation in church, his thoughts are drawn in a different direction. His observations,

through the eye and through the ear, draw him into an association with

the “Joan-girl” — his own specific wife — and then a judgment on men,

as “scribes, pharisees, and thieves”, which exist in a different zone. I hope that your reading of the letter has offered a kinder, gentler

Kerouac.

There is something else, though.

Kerouac's vision that day came to him in connection with tears. Something “got through”, but it was in connection with tears. I wonder sometimes why people cry in church. Happens all the time. People who are “normally” well- and tightly- put together, “lose it”

during the singing of a hymn, or an illustration in a sermon, or

something they see out of the corner of their eye. It's as if you go “out of your mind” for a minute, or “come to your senses”, or are “touched” in a deep uncovered emotional part of you. As I say, this seems to happen all the time.

It happened to me the other night. Just like it happened to Kerouac — but it was me and not him.

I stumbled across something I only dimly remembered. It was on

YouTube, and I stumbled over something I only dimly remembered. It was the last two minutes or so of an 'X-Files' episode entitled “The

Post-Modern Prometheus”. I remembered it as a kind of visual 'send-up' of the James Whale

Universal horror movies I loved so much as a child. In “The Post-Modern Prometheus”, a “Frankenstein's-Monster” is located,

by Mulder and Scully, and saved by them. The ending, however, I had not remembered.

It takes place in a crowded nightclub, and Cher takes the stage — at

least a look-alike — and belts out the song “Walking in Memphis”. Not only does the 'Monster', who is seated at a table in the front row,

together with Scully and Mulder, jump right up and dance ecstatically

to the song — that EXCELLENT song. But then Mulder beckons to Scully to join him on the

floor. Our frosty and usually confused “couple” get the message, of the song

and of the place. They dance together, romantically and intimately, and touchingly.

“Frankly, Neal, I began to cry.”

I began to cry. Really cry. All choked up. Tears of joy, tears of feeling — feelings actually about my own wife,

my own “Joan-Girl”.

Then I decided to write this piece.

Ideas seem to come this way. You don't control them, or muster

them up, or command them to appear.

They come up through the emotions.

But it's often the eye that gets the ball rolling.