From the 80s, I think.

Booklovers will understand the meaning of this. I sometimes seek, and in fact currently possess, imaginary books.

From the 80s, I think.

Booklovers will understand the meaning of this. I sometimes seek, and in fact currently possess, imaginary books.

And malt does more than Milton can

To justify God's ways to man.

— A. E. Housman

The great caricaturist Drew Friedman recently designed the label above for one of McSorley's house brews. McSorley's, in downtown Manhattan, is the oldest continuously operating bar in New York, going strong, or at least going, since before the Civil War. It has a special place in my heart, for it was there I began my lifelong love affair with beer.

In 1968, I spent the summer of my 18th year in the East Village, NYC, in an apartment near McSorley's. The bar had not at that time been adopted by NYU frat boys, and was a dive, little changed from the 19th Century. Old, grizzled men, many of them retired merchant seamen, hung out there in the afternoons drinking the fine house ales and filling up on the cheap sandwiches sold at the bar. The drinking age was 18 back in those days, and my friends and I hung out there in the afternoons, too. It was a grubby but magical place. It looked exactly the way it looks in the 1912 painting below by John Sloan:

Women were not allowed in McSorley's then — a 19th-Century policy that would soon be challenged by feminist activists. The first of them who walked in and demanded to be served got a pitcher of beer emptied over her head. The courts eventually ruled that McSorley's could not legally bar women. This opened the way to its current status as a hipsters's joint. It still looks the same as it always did but cannot be visited by sane people at most hours of the day and certainly not after dark.

I'm glad that women are served there now, of course, and its popularity will insure its survival for another century or so, but the hiraeth comes upon me when I think of it as it was once — the hiraeth, a Welsh word that means “the longing for what has been”.

The quote above (thanks, Django) is from a poem by Housman called “Terence, This Is Stupid Stuff”, which also contains the following lovely lines:

Oh I have been to Ludlow fair

And left my necktie God knows where,

And carried half way home, or near,

Pints and quarts of Ludlow beer:

Then the world seemed none so bad,

And I myself a sterling lad;

And down in lovely muck I've lain,

Happy till I woke again.

There are 1000 guys in Lowell who know more about heaven than I do.

— Jack Kerouac

Jack Kerouac left an amazing portrait of America in the second half of the 20th century — paying attention to the everyday warp and woof of things and their mythic role in the unconscious epic of the nation. To find anything comparable in the art of our time you have to look to the photographs of Walker Evans and William Eggleston, especially Eggleston.

Kerouac celebrated and eviscerated American places in long, impressionistic passages in his writing and in brief epithets tossed off in passing. These epithets, taken together, have something of the quality of the Catalog Of the Ships in The Iliad.

Paul Zahl, a regular contributor here, discusses Kerouac's geographical epithets, about America and other places, with some choice examples:

A JACK KEROUAC GEOGRAPHICAL GLOSSARY

by Paul Zahl

Kerouac had a wonderful way with vivid adjectival phrases.

In his letters especially, and wherever he could write free of

stricture or zealous editor, he would use jammed-together phrases to

describe the places he visited, the people he met, and the phenomena he

observed.

I have made a little study of Kerouac's descriptive phrases for the

cities and towns, and even foreign countries, in which he spent time.

For example he described Morocco as the place where one could see “the

true glory of religion once and for all; in these humble, often

mean-to-animals people”.

If you have spent time in a Middle-Eastern country, this phrase

instantly connects. How many people I know who have left their

inherited religion in the West and are impressed by exactly the phenomenon

Kerouac observes, right down to the flogging of the camels.

Here is a little 'Beat' geographical glossary, from the man who saw,

and wrote what he saw.

Oh, and some of them may offend you if you actually live in the place

he is describing. When Kerouac refers to “rainytown Pittsburgh”, he

captures the essence of that particular city. But Pittsburghers don't

see it this way at all!

So hold on to your hats. And get ready to smile, and maybe wince a

little.

(All these phrases come from the letters of Jack Kerouac composed

between 1957 and 1969, which are collected in the 1999 Viking Press publication edited by Ann Charters.)

Rock n Roll Hooligan England

sick old Buddhaless Europe

California TOO MANY COPS AND TOO MANY LAWS and general killjoy culture

Total Police Control America

Doom Mexico

(Kerouac survived an earthquake in Mexico City, and was

also fascinated by the interest in death which he saw in the culture

there.)

“Orlando Florida”

(Kerouac complained that you could not buy On the

Road at any newsstand in Orlando, where he and his mother lived for two

fairly long periods, so that city for him would always be in quotes.)

nightmare New Orleans

thank God for Spain! All living creatures are Don Quixote

San Francisco, that town of poetry and hate

unholy Frisco

Muckland Central Florida in Febiary (sic)

midtown New York sillies world

this New York world of telephones and appointments

peaceful Florida, winter Florida, Florida peace

Massachusetts boy-dreams of Harvard

the South where everybody is DEAD

And thinking globally . . .

so goes the Dostoyevskyan world

And from Visions of Gerard . . .

That hat, with its strange Dostoyevskyan slant, belongs to the West,

this side of this hairball, earth

the world, the uncooperative and unmannerly divisionists, the bloody

Godless forever

Home again . . .

overcommunicating America

You could probably write an essay on every pungent phrase that Kerouac

comes up with. You may also be offended by his incautious descriptions. Furthermore, they were mostly written down under the influence of

alcohol, by the author's own admission.

Yet they are evocative and at times (to me) inspired. They are also

very funny. After just a few days in London, thirty years before the rise of the

“soccer yob”, Kerouac spoke of “Rock n Roll Hooligan England”. What prescient voice is this?

If this starter glossary re-connects you with Kerouac's

voice, the voice of a man Allen Ginsberg described as “heaven's recording angel',

and sends you back to his work, try writing down more of these phrases as they catch your eye. As your Catalog grows you'll wonder, “Where did this man receive his wisdom?” and “Did

he not grow up right here in Nazareth, and do we not know his mother

and his brothers and his sisters?”

[Editor's Note: “Overcommunicating America” — we live there now, all right. And even a man who could write, decades ago, “California TOO MANY COPS AND TOO MANY LAWS and general killjoy culture” might be surprised at the way The Wellness State has calcified into his most extreme vision of the place. Jack apparently never visited my hometown, Las Vegas, but he would have nailed it, too, I imagine, in a way that would make me wince . . . and laugh. Paul Zahl just moved away from a suburb of Washington, D. C., where Kerouac and Gregory Corso once dropped in unannounced on the poet Randall Jarrell and found him “hobnobbing in Chevy Chase”, a world center of hobnobbing. Kerouac will find you wherever you are, America — you can run but you can't hide from heaven's recording angel.]

The map above is from one of Kerouac's diaries. The portraits are by Tom Palumbo. You can find more of Paul's articles in The Zahl File here.

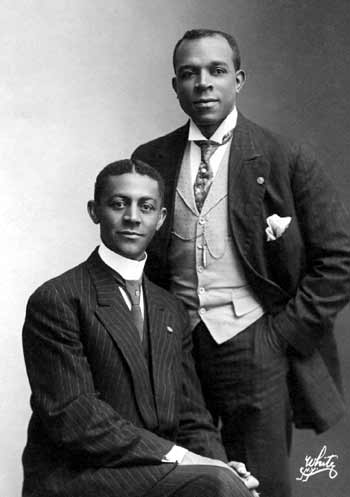

Thomas Riis's fascinating book Just Before Jazz examines the influence of black composers and performers on American musical theater between 1890 and 1915 — that is, just before the era in which the modern book musical began to take shape.

The songs of black composers were very similar in many ways to the popular songs written by white composers, even the white composers of operettas. A number of black composers in this period (like Will Marion Cook, below) were highly sophisticated, classically trained musicians, capable of writing and performing in any style. (Many of them were “slumming” in popular theater because of barriers to their involvement in more refined areas of practice.)

What distinguished their work was the incorporation of the sort of syncopations found in ragtime, which became a popular sensation around the turn of the century. Their work didn't emphasize such syncopations to the degree that ragtime did — they were more like stylistic inflections — but they thrilled audiences of the time.

Among the most popular songs in this period, an astonishing percentage were written by black composers, and they included not only minstrel-type songs but ethnically neutral ones. It was the purely rhythmic lilt that made the difference.

Almost all of these songs were first done for musical shows originating in New York City, often in Broadway productions, leading Riis to argue that black composers bear the primary credit for introducing black musical strains into the American musical. Berlin and Kern and Gershwin weren't “reaching down” into an exotic black musical culture for inspiration — they were responding, artistically and commercially, to developments in the world of musical theater all around them.

You have to wonder why these black composers aren't better known today. Partly it's because the lyrics of many of their songs are offensive to modern ears — the “coon song” was a typical genre, with its caricatures derived from minstrel shows. As black songwriters became more powerful, however, they toned down the uglier aspects of these caricatures, leaving stereotypes comparable to those attached to other ethnic groups like the Irish and the “Dutch” (as Germans were once called.) These stereotypes aren't congenial to our present tastes, perhaps, but they aren't exactly vicious, either.

More importantly, these black composers failed to achieve wider celebrity, and failed to enter our cultural memory, because they could not participate fully in the flowering of musical comedy in the later decades of the 20th Century. Their songs were bought and performed by white performers in vaudeville, were sometimes interpolated into shows with white casts and were disseminated nationally via sheet music, but in the theater, they wrote primarily for all-black shows. Broadway had a place for such shows, but it was a limited place.

Black composers were very rarely hired to provide complete musical programs for shows with white casts — they never became part of the mainstream of producers, musicians and writers who created the ordinary run of Broadway musicals. White composers adapted the style of their black peers within an establishment that stayed predominantly white.

So today, when we hear Judy Garland and Margaret O'Brien singing “Under the Bamboo Tree” in the movie musical Meet Me In St. Louis, we likely have no idea that this song, a monster hit in 1903, with a tune that is still familiar and still infectious, melodically and rhythmically, was written by three black men, James Weldon Johnson, his brother Rosamond Johnson and Bob Cole. Below, a portrait of Cole and Rosamond Johnson:

But the past, of course, as an old Russian saying has it, is always unpredictable.

A hunt. The last great hunt.

For what ?

For Moby Dick, the huge white sperm whale: who is old, hoary,

monstrous, and swims alone; who is unspeakably terrible in his wrath,

having so often been attacked; and snow-white.

Of course he is a symbol.

Of what ?

I doubt if even Melville knew exactly. That’s the best of it.

— from Studies In Classic American Literature

Image by Rockwell Kent.

Show me a man who lives alone and has a perpetually clean kitchen, and

eight times out of nine I'll show you a man with detestable spiritual

qualities.

“I want to know what it says, the sea. What it is that it keeps on

saying.”

— from Dombey and Son:

If you lean in close, so I can whisper in your ear, I'll tell you . . .

Love lasts forever

Love never lasts

Love lasts forever

Love never lasts

Love lasts forever

Love never lasts

Love lasts forever

Love never lasts

Hush

Hush

Hush

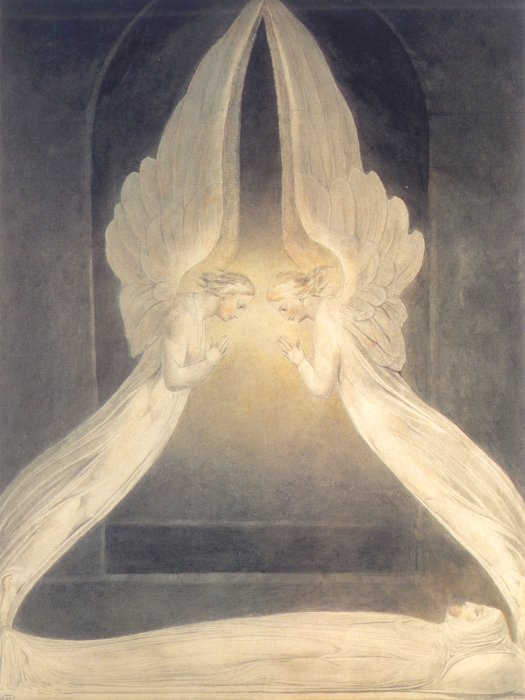

“What,” it will be Question'd, “When the Sun rises, do you not see a

round disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?” Oh no, no, I see an

Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying, 'Holy, Holy, Holy, is

the Lord God Almighty.'

— William Blake

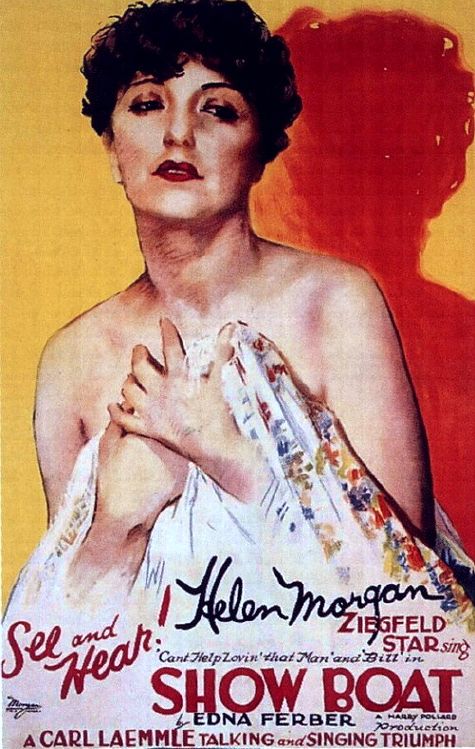

Edna Ferber's Show Boat isn't a great novel but it's great fun — a good story told in a lively way.

It's easy to see, too, why it appealed to Oscar Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern as material for a musical play. It's a book infused with a sentimental love for theater and nostalgia for the romance of its bygone days.

The era of the show boat, coming to an end when Ferber published the book in 1926, is presented as a kind of lost Eden of American show business, somehow magically recovered by modern performers who remember the old ways.

It also deals quite explicitly with the most crucial but often disguised conversation at the heart of American popular entertainment — that between whites and blacks. (Above is a portrait of Jules Bledsoe, the stage musical's original Joe.) Ferber is sensitive to the dynamic quality of this conversation and also to the injustice and hypocrisy that inform it. Julie Dozier, the actress of mixed race expelled from the Eden of Captain Andy's Cotton Blossom, is both an emotional and theatrical inspiration to the novel's (white) female protagonist, Magnolia Hawks. It is only race that condemns Julie, along with all African-American performers, to a life on the margins of show business, and Ferber's book bristles with outrage over this. (The poster below features Helen Morgan, the stage musical's original Julie, who reprised her role in the 1929 part-talkie film version.)

Hammerstein and Kern, like most show folk, were clearly sentimental about “the business”, and like most lovers of American music, they were both inspired and instructed by black musical culture. It remains astonishing, some eighty years on, that they had the ambition to deal with these themes in such a mature and serious way in their stage production of Show Boat. It was ahead of its time in 1927, and in some ways it remains ahead of our time, too.

Kern's music, of course, exists outside of time, and would have been a miracle in any age.

The stories of women go unheard, I heard her to say, Lila.

“No one knows what happens to women. No one knows how bad it is, or how good it is, either. Women can’t talk — we know too much.”

From the short story “Ceil” by Harold Brodkey, published in The New Yorker, 1983.

[Image: “Venus Rising From the Sea — A Deception”, by Raphaelle Peale, 1822.]

I can't exactly recommend this book, because it's so grim and harrowing, but I can report that it's one of the most important books ever written about the Civil War, and about war in general. It takes a frank and even brutal look at the phenomenon of mass death on American soil between 1861 and 1865, and allows you to get in touch, at least partially, with the unspeakable horror of it. It's certainly an indispensable book for anyone, like myself, who's ever been infected with the “romance” of the Civil War, or of war in general.

About 600,000 soldiers died in the Civil War, plus an uncounted and today uncountable number of civilians. As a percentage of the U. S. population now that would work out to over 2,000,000 people. Faust does her best to give us a sense of how the survivors tried to cope with this ghastly slaughter — emotionally, spiritually, politically, philosophically and physically. It was an epic endeavor. On the most basic level, the physical, no one was prepared for the task of disposing of so many tons of rotting meat that had once been human beings. On a higher level, there were no rituals of mourning in place for loved ones who died so far from home, often suddenly, without warning, and so conceivably “unprepared” to meet their Maker, and whose bodies in tens of thousands of cases remained unidentified and unrecoverable.

Faust, for once, deals equally with the mechanics of death and with its lasting consequences for those survivors who had to manage its effect on their own lives.

The Civil War dead cast long shadows, and we stand among those shadows today, whether we know it or not.

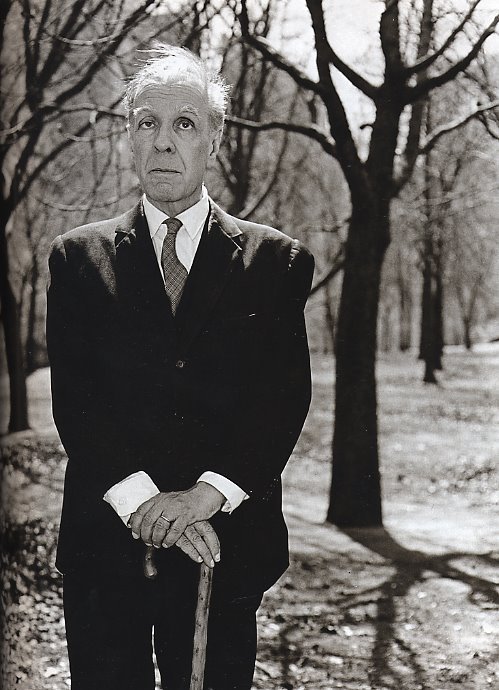

The instinctive is what counts in a

story. What the writer wants to say is the least important thing; the

most important is said through him or in spite of him.

[Portrait of Borges by Diane Arbus.]

“Harold Pinter is dead.”

“His plays were hard to understand.”

“Yes, but he's dead.”

“The characters seemed like they came from different plays.”

“Cancer.”

“What?”

“He died of cancer.”

“Cancer?”

“Yes, it killed him.”

Pause.

“So . . . Harold Pinter is dead.”

“Dead as a doornail. Of cancer.”

“Ah.”

Long pause.

Une femme qui tolère votre sommeil fait plus que vous aimer, elle vous pardonne d'exister.

(A woman who tolerates your sleeping does more than love you — she pardons you for existing.)

— Philippe Sollers

[With thanks to Femme Femme Femme for the quote — image by Cabanel, a Victorian painter famous for his historical and mythological works, which tended to be florid and a bit silly, but whose portraits could be very fine, indeed.]

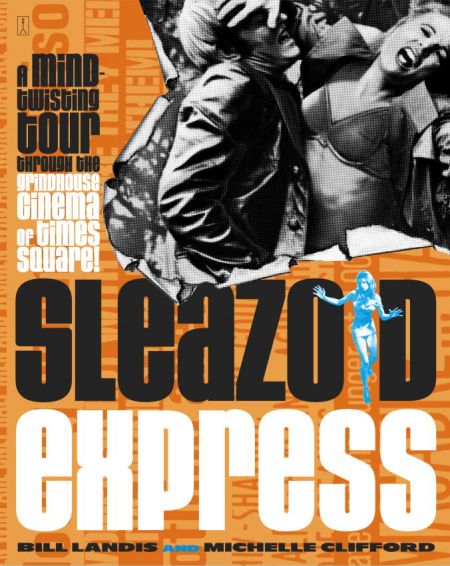

Over on Illusion Travels By Streetcar, Tom Sutpen has posted a poetic tribute to the book Sleazoid Express, which summons back the long-gone days of pre-Disney 42nd Street in Manhattan, when former legit theaters which had become grind movie houses showed exploitation films to the hustlers and grifters who called that part of town home.

As it happens, I was just watching an interview with Michael Eisner about Disney's decision to refurbish the New Amsterdam Theater on 42nd street, which had fallen below even grind-house standards. Its grand interior, which once housed the Ziegfeld Follies, was open to the elements and home only to birds. Eisner describes telling Rudolph Giuliani, then the mayor of New York, of his fears that family audiences might not feel comfortable visiting that part of town, with its grind houses, sex shops and massage parlors. “They will be gone,” said Giuliani.

“They can't just 'be gone',” Eisner said. “I mean, you've got the ACLU, free speech.” “Look in my eyes,” Giuliani said, and repeated, “they will be gone.”

By the time The Lion King opened in the beautifully restored New Amsterdam, they were gone. Sleazoid Express is about what was swept away to make room for Simba and company.

Sutpen suggests why we should remember this lost world, which is why we should remember all the “unexamined” aspects of our culture — because they often provide greater insight into who we really are than cultural manifestations which have the full support of city police departments.

Back in 1908, when 42nd Street was an upscale theatrical Mecca, nickelodeons, the grind houses of their day, were showing the first films of D. W. Griffith. In sleazy dives on the shabbier side streets you could hear “Negro music”, the precursor to jazz. In other words, there was a time when the two great art forms of the 20th Century were part of America's marginal culture, its unexamined culture.

Whatever the exploitation films of the Sixties and Seventies represented, it was important, and it isn't gone. By the same token, as Sutpen notes, the Times Square Renaissance, which turned a scary part of town into a family-safe part of town, also began a process by which Manhattan has been transformed into a mall-like environment for tourists, losing its urban juice and spirit. What began as a rebirth in Times Square inaugurated a kind of lingering death for one of the world's great cities.

Culture, too, has its own circle of life.