I've had many strange experiences in Las Vegas, but none stranger that seeing David Irving speak in a small banquet room at the Jokers Wild Casino, a little locals' joint on Boulder Highway, at the edge of town.

Irving is a very controversial historian of the Third Reich whom I've written about before, here and here. The most prodigious researcher in the German archives pertaining to National Socialism, and in the archives of the Allies that house captured German documents on the subject, Irving has written a series of books which are essential compendia of facts about Hitler and his state. But he has a bias — a desire to show that Hitler and the Nazis weren't as bad as everybody thinks, and that the Allied leaders were far worse than anybody thinks.

His motives in this are suspect, since he occasionally reveals anti-Semitic attitudes that offend the conscience, but his facts are always right, even if he marshals them to serve a twisted argument. His books are respected, with reservations, by respectable historians, but he has been vilified mercilessly by just about everybody else.

He was imprisoned for over a year, in solitary confinement, in Austria for giving a speech in which he noted that the gas chambers at the Auschwitz historical site are reconstructions, which is true, and arguing that gassing was not in fact used systematically to kill prisoners there, which is hotly contested by other historians and by eyewitnesses. His words were thought to violate Austrian laws against Holocaust denial.

Irving is not exactly a Holocaust denier — more of a Holocaust minimizer. He admits that many bad things were done to Jews by the Nazis, just not as many bad things as historians have claimed. And he insists that Hitler was out of the loop as far as the Final Solution was concerned — that Himmler instituted mass killings on his own hook, so that the “Messiah” of the German Reich would not be tainted by the policy.

This strains credulity, of course — imagining that a faithful lieutenant would do something so momentous on his own, something which Hitler would be held accountable for even if he knew nothing about it. Still, Irving can point to the fact that no document recording Hitler's acquiescence in the mass extermination of Jews survives, and that Himmler regularly removed allusions to the policy from reports he passed on to the Führer.

It strikes me as more likely that Himmler simply had an understanding with Hitler that the policy of extermination would not be referenced in high-level documents of any kind, so that Hitler would never have to contend with opposition to it from his high-placed generals and ministers, and that Himmler would take the fall for it politically if it ever became generally known. It wouldn't be the first time a politician used plausible deniability to try and cover his ass.

It's equally possible that documents recording Hitler's involvement in the Final Solution were destroyed before or during the apocalypse of Germany's collapse.

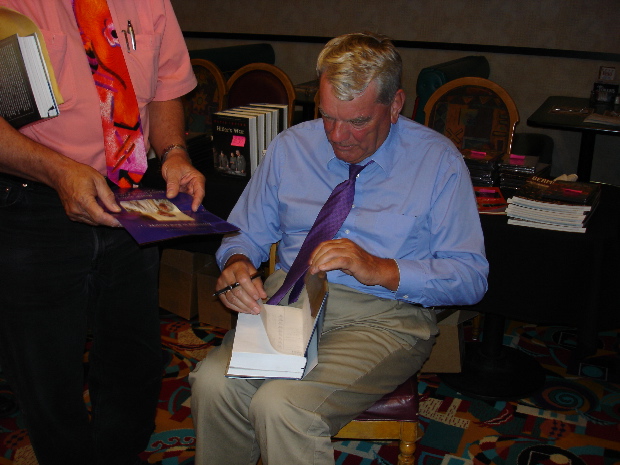

When I showed up at the Jokers Wild Casino I almost bumped into Irving as he wheeled a cart with boxes of his books into the place. I greeted him but he hurried on gruffly, perhaps embarrassed by being seen in shorts and a sports-shirt hauling his own merchandise.

His talk was held after a buffet dinner, included in the price of the lecture, in a small private room off the casino's coffee shop. The food was school cafeteria quality and barely warm. There were about eleven other people in attendance. I kept to myself, fearing what sort of conversations my fellow attendees might initiate. I overheard one older guy railing against democracy — “It allows people to let off steam, to think they have some say over their government. America isn't a government, anyway . . . it's a corporation.”

Irving's talk was generally reasonable. He spoke at length about his imprisonment, and the tale was genuinely harrowing. Irving reported to the outside world that the library of his prison contained several books he had written. At this point, a high Austrian official ordered all books by Irving in all Austrian prisons to be removed and burned — “To show the world that we have moved beyond the Nazi era.” The minister seemed to see no irony in using a book burning to demonstrate this point.

Irving then talked about his forthcoming biography of Himmler, which he promised would put to rest once and for all the idea that Hitler knew about the Holocaust. He said he expected to endure further persecution upon its publication.

Irving said a few troubling things. He said he told the Austrian press when he was finally released from prison that “Mel Gibson was right.” He didn't elaborate on this in Austria, but to us he explained, “You know, about who started all the world's wars.” In other words, the Jews. He said that Churchill did not become anti-Nazi until after he was paid 48 thousand pounds by a Jewish organization in 1936 — an amount, Irving said, worth about 3 million dollars in today's currency. The implication was that all of Churchill's fine rhetoric was bought and paid for by Jews.

An odd evening with an odd man in an odd place in an odd town. That's Vegas, baby.