Puritanism is the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.

Puritanism is the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.

The third of the four coolest books published in the past few years is (I am compelled to report) also from Sunday Press Books — a collection of Winsor McCay’s pre-Nemo comic strip Little Sammy Sneeze.

This book is not a gigantic volume reproducing newspaper pages in full size, simply because Little Sammy did not command a full page on Sundays. It is, instead, a good-sized coffee-table book — all that’s needed to reproduce McCay’s color Sammy Sneeze strips almost exactly as they were originally published.

Sunday Press’s philosophy in regard to reproducing old color strips is

very sensible. They use modern digital techniques to correct the

fading of colors and the yellowing of paper, but don’t try to improve

on the colors as they would actually have appeared to a reader of the

time and don’t try to eliminate minor characteristic printing

errors. What one sees in their books is thus a very close

approximation of the medium the comic strip artists composed for.

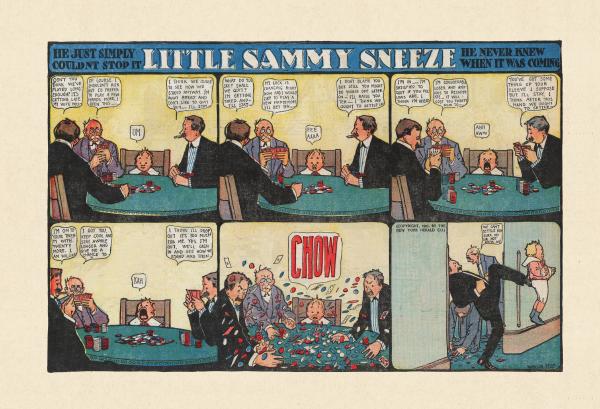

In Little Sammy Sneeze, McCay took a very small idea and made something wonderful out of it. The strips normally employ either six or eight panels, all showing the same location and generally from the same point of view. Activity proceeds within the space of the location as Little Sammy works himself up to a sneeze, which usually produces catastrophic effects within the location and causes Sammy to be ejected from it angrily. For some reason, this mechanical formula produces endless delight — much the way simple variations on a musical theme can produce endless delight.

The drawing, of course, is brilliant, as you’d expect from McCay, and the period detail within the mostly realistic settings has only grown more magical with time. The strips are in part about time, of course — small segments of time in which many things happen.

Seeing the way static pictures on a page can evoke a sense of the passage of time is intrinsically fascinating. It’s like deconstructing the process of cinema, with the illusion laid out anatomically before you.

In one instance, McCay deconstructs his own medium, as Sammy’s sneeze fractures the frame of the comic strip panel itself:

If the gag in the strip is always the same, or more or less the same,

it is nevertheless always surprising — or perhaps one should say

always suspenseful. There’s a psychological phenomenon involved

here that’s at the core of any good joke, which can make you laugh even

if you’ve heard it before. In part, it’s the shape of the joke that

makes it work — a tension is created that can only be resolved with

the release of a laugh. The same phenomenon is at work in all

stories, which is why it’s possible to cry every time you read A Christmas Carol — even if you know it almost by heart.

You can obtain Sammy’s sneezes here.

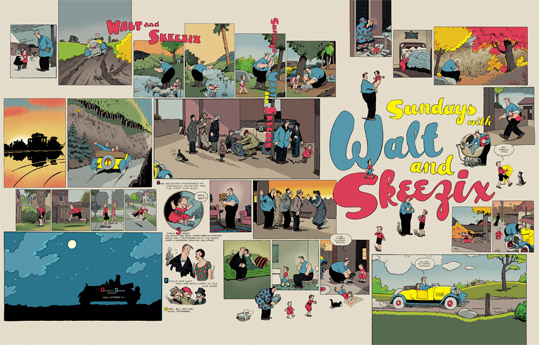

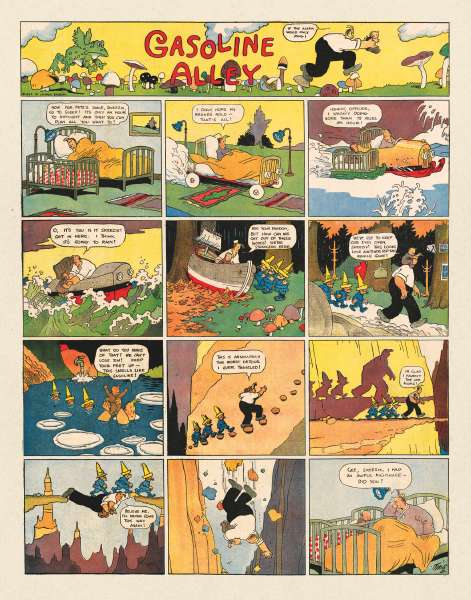

The second of the four coolest books published in the past few years is another oversized volume from Sunday Press Book — Sundays With Walt and Skeezix. It collects a number of Sunday pages from Frank King’s brilliant long-running strip Gasoline Alley,

one of the glories of American popular art. I’ve written before about the

series from Drawn and Quarterly Press which is reprinting the entire

run of the daily strip in a succession of handsome volumes — but the Sunday

pages are something else again.

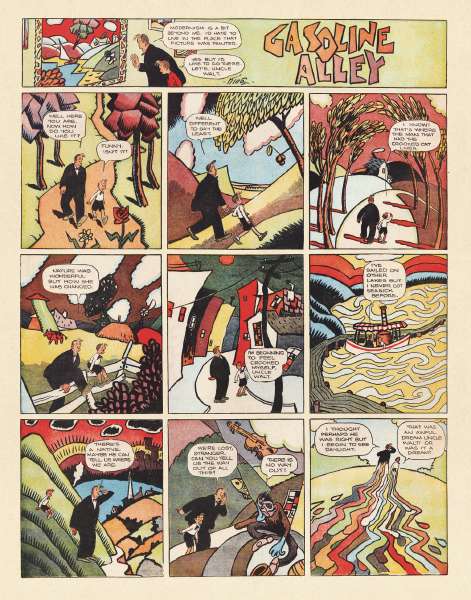

In the daily strip, King created a narrative masterpiece graced with

many flights of visual invention, but in the color Sunday pages his

visual imagination grew much bolder — lyrical, almost abstract at

times. He looked at the Sunday page sometimes as an arena for the

wildest experimentation — to see just how far the expressive potential

of a comic strip might reach.

In the Sunday Press collection we can see these Sunday strips almost as

their first viewers did — in the same colors and in the same size.

It’s a measure of our culture’s descent into mediocrity and triviality

that no work of such ambition and grace now accompanies any daily

newspaper in the land, and certainly no cable news channel. It

used to be assumed that the visions of great popular artists ought to

be part of every American’s daily dose of media. Today only cheap

digital graphics and portentous musical jingles accompany the canned “news”

doled out by the major media outlets.

Americans have never liked being spoon fed “culture” — meaning culture

that somebody decided was good for them. That was the beauty of

the comic strip — it was an art form so unpretentious, so vernacular

and casual, that Americans could consume it over breakfast or before

dinner without a trace of self-consciousness or social anxiety. But its

expressive range was almost limitless. We know that from the work

of artists like Frank King, who in their own quiet but audacious ways

tested its limits to the full.

You could read through these comics and weep that stuff this great used

to be thrown up on the porches of millions of Americans by

paperboys every Sunday morning — and isn’t anymore. Or you could read through them

and take heart at the fact that stuff this great could ever have been part of

American popular culture — and so might be again. Why not?

You can buy Sundays With Walt and Skeezix here.

The

four coolest books published in the last few years all reprint work by

masters of the American comic strip. These books are so cool,

so unspeakably cool, that when I look at them I can’t quite believe

they’re real. But they are.

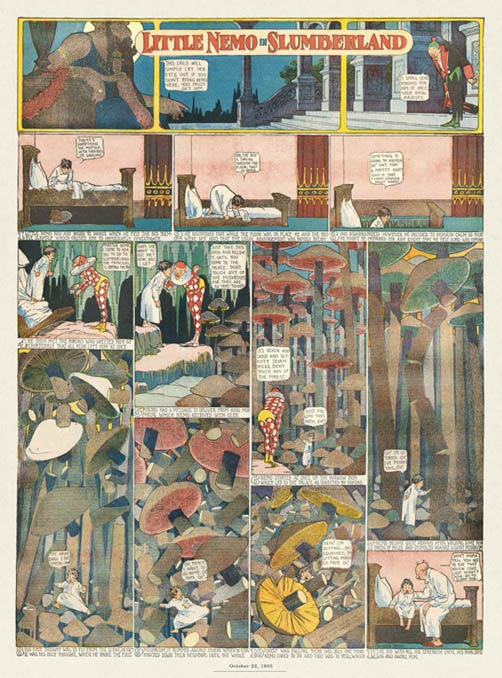

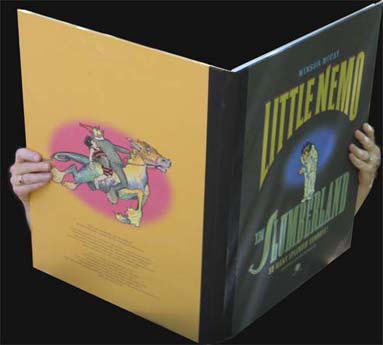

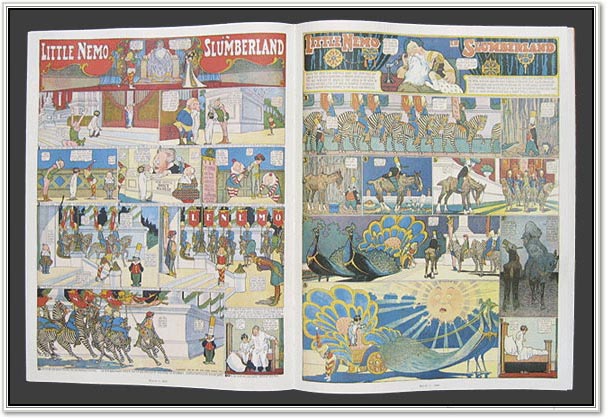

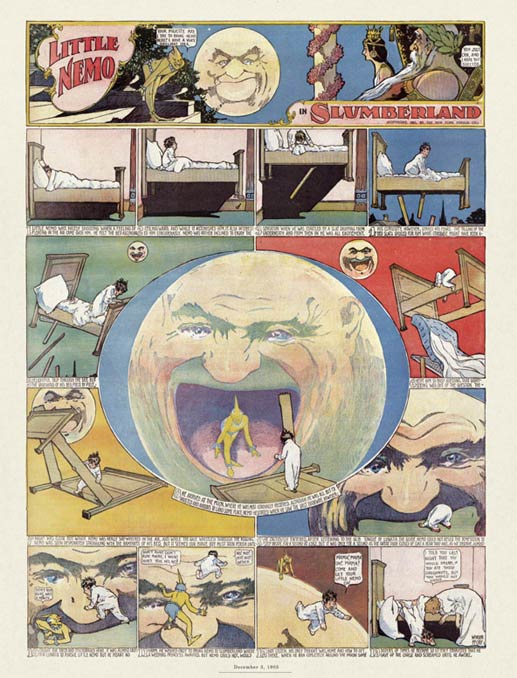

The first of them, Splendid Sundays 1905-1910, is a huge volume that reprints in full size many of the Sunday color episodes of Winsor McCay’s classic strip Little Nemo.

McCay was the most cinematic of all comic strip artists — he created

fantasy worlds that are visually plausible but wildly whimsical,

exploding with dazzling transformations and dynamic movement through

deep spaces.

One should also say that McCay was not by any means the wittiest of all

comic strip artists, nor the best storyteller among them, but the

visual imagination of his strips transcends those limitations.

The strips reveal their brilliance more fully the better and

bigger his work is reproduced. That’s the importance of Splendid Sundays, which

for the first time in nearly a hundred years lets us see the strips in something resembling the

medium for which they were created — a full-sized newspaper page.

With even small reproductions of the Nemo

strips we can sometimes feel as though we’re falling into the spaces of

Nemo’s nighttime dreamworld. With Splendid Sundays we tumble headlong into

that world — and it’s a truly magical place to be. Sunday Press

Books has done a signal service to our culture in creating this huge

and hugely wondrous book.

You can buy it here.

. . . the pang of affection & gratitude is the Gift of God for good. I am

thankful that I feel it; it draws the soul towards Eternal life &

conjunction with Spirits of just men made perfect by love &

gratitude—the two angels who stand at heaven’s gate ever open, ever

inviting guests to the marriage. O foolish Philosophy! Gratitude is

Heaven itself; there could be no heaven without Gratitude. I feel it

& I know it. I thank God & Man for it . . .

Writing is an occupation in which you have to keep proving your talent to people who have none.

The

influence that went on, back and forth, between the cinema and other

visual arts has often been noticed but rarely studied in detail.

Writers on cinema have produced tome after tome about the influence of the

stage and literature on movies, but the visual side of things has

rarely been subjected to rigorous investigation.

Partly this is because the two principal visual influences on movies,

comic strips and Victorian academic painting, have had little prestige

in the scholarly culture, and partly it's because these two forms have

been hard to study themselves. First-rate reproductions of even

the most important comic strips have been difficult to come by, and

Victorian academic painting tends to languish in storage in museums, to

make room in the galleries for the junk creations of “modern art”.

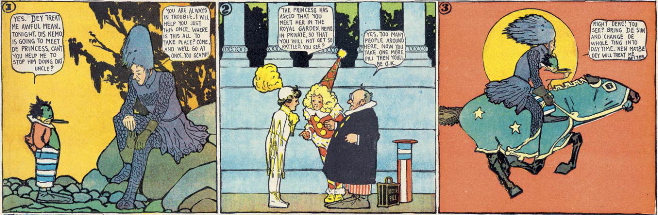

With respect to comic strips, things are changing. Splendid reproductions of seminal strips like Popeye, Gasoline Alley and Terry and the Pirates

are becoming available in ongoing series, and Winsor McCay is getting

spectacular treatment in large over-sized volumes which do full justice

to his amazing visions. (See here and here.)

New revelations about the connection between comic strips and movies should

follow. Here's a brief slideshow (via Boing Boing) created by a critic at the Boston Globe

which surveys some of the most obvious ways Winsor McCay's work has

influenced the iconography of movies. It's based on observations in a new collection of McCay's strip Dream Of the Rarebit Fiend. More complex issues of

narrative technique and composition will surely come to the fore in the

future. [McCay created some of the earliest animated cartoons, so

his influence on film animation has long been appreciated, but his

influence on movies in general was far more comprehensive, as the

slideshow suggests.]

If you want to contemplate the connection between cinema and Victorian

academic painting you will just have to settle at present for my

passing observations in the essays collected here.

Here's a poem in French by Henri Michaux, Ma Vie:

Tu t'en vas sans moi, ma vie.

Tu roules.

Et moi j'attends encore de faire un pas.

Tu portes ailleurs la bataille.

Tu me désertes ainsi.

Je ne t'ai jamais suivie.

Je ne vois pas clair dans tes offres.

Le petit peu que je veux, jamais tu ne l'apportes.

A cause de ce manque, j'aspire à tant.

A tant de choses, à presque l'infini…

A cause de ce peu qui manque, que jamais tu n'apportes.

Here's a rough translation:

You're going away without me, my life.

You're rolling on.

And I'm still waiting to make my first move.

You've taken the battle elsewhere.

You've deserted me.

I never followed you.

I've never seen anything in what you offer.

The little I want you never bring me.

Because of this I want so much —

So many things, almost everything . . .

Just because of this pittance I lack, that you never bring me.

Reading Hitler's War,

David Irving's massive, exhaustive study of WWII as seen from Hitler's

perspective, is riveting but spiritually exhausting. We will

never have a more sympathetic portrayal of Hitler and his motives, at

least not one consistent with the purely factual record, but what vapid

company the Führer turns out to be. Even the glamor of evil can't

redeem him and his henchmen from their utter banality, from the sheer

colossal mind-numbing stupidity of their fear of and paranoia about “world

Jewry”. As they grow in power their puny souls seem smaller and

smaller — consistent with the bunch of clever, fanatical, provincial

hacks they were. It will be to Germany's eternal shame that it

consented to be led in momentous times by such mediocre shadows of men.

A useful specific for the soul-sickness induced by Irving's book is Ken Burn's 15-hour documentary The War.

It's not without its passages of moral self-congratulation, but its

greatest value lies in its willingness to confront the darkness that

the war summoned up in the victors, especially in the young men who had

to fight it on the front lines. In the filmed interviews, the American combat

survivors — old men looking back on the war after more than half a

century — still tremble when they recall what they had to do, still seem

mystified that they could do it.

Like the Germans and the Japanese, the good guys in this war learned to

kill without mercy — even to kill defenseless civilians and unarmed

prisoners. And sometimes they experienced an exhilaration in

killing. The experience shook their souls and by the evidence

they never really got over it. The fact that they won a “good

war”, or a “necessary war” as one of them prefers to call it, didn't

heal the wounds within.

Hitler, and the Japanese warlords, sought to glorify the merciless

killing of war — sought to embrace it as a given of nature. The

soldiers of the great democracies may have recognized it as a given of

nature, but their refusal to glorify it, to accept it willingly as a part of who

they were, even in a just cause, makes for a startling contrast to

the supposed “realism” of a man like Hitler. It gives the heart a

little breathing space in a heartless world.

It's from Twelfth Night.

Trip no further, pretty sweeting,

Journeys end in lovers meeting . . .

Are there any lovelier lines in all of English poetry?

What I like about them most is that they combine the lover's faith with the storyteller's faith.

The reference to singing both high and low is apparently mildly obscene, but I'll leave the details of it to your imagination.

The carpe diem message of the

song is not unusual, but the gossamer delicacy of the tone is

rare. As I've suggested before, A. E. Housman got it down pretty

well:

Clay lies still but blood's a rover,

Breath's a ware that will not keep.

Up, lad, when the journey's over

There'll be time enough to sleep.

These, in the day when heaven was falling,

The hour when earth’s foundations fled,

Followed their mercenary calling,

And took their wages, and are dead.

Their shoulders held the sky suspended;

They stood, and earth’s foundations stay;

What God abandoned, these defended,

And saved the sum of things for pay.

The title of this poem is Epitaph on an Army of Mercenaries.

It’s one of my favorite poems of all time because it looks at things so

coldly and reminds us that sincerity is not the highest of

virtues. Today we tend to think of virtue as a state of mind —

if you mean well, you’re a good person. To Housman, as to the ancient Greeks, virtue was action, pure and simple.

When he died in a car crash this Spring, David Halberstam had just finished his 21st book, The Coldest Winter,

an epic study of the Korean War. It's partly a work of military

history, with combat narratives based on interviews with veterans of

the conflict, but its greater value lies in the way Halberstam places

the war in the context of the post-war world, of American and global politics and strategy.

It fills in yet another piece of the puzzle of America's mood after

WWII — dark, anxious, bewildered, unsure of its new role as a world

superpower, veering between arrogance and lunatic paranoia.

There are many lessons for our own times to be learned from the book —

not least about the ways the Republican party managed to box the

Democrats into policies they mistrusted under the threat of being labeled

“soft on Communism”. Substitute “terrorism” for “Communism” and

you will see the same dynamic at work today.

The war in Korea all but wrecked Truman's presidency, but he was

confident that history would judge him more kindly than his

contemporaries, as indeed it has. Among the high-ranking soldiers

and politicians, Matthew Ridgway and Truman emerge in Halberstam's book

as the true heroes

of the war. Ridgway learned how to fight the Chinese because he

was willing to take them seriously, to respect them as soldiers,

something the racist high command under MacArthur could not do.

Truman was willing to buck popular sentiment and

risk political ruin to oppose MacArthur, whose madness served the purposes

of the right-wing Republicans in Washington but whose insubordination

threatened the very core of the American system of government, the principle of

civilian control of the military.

Among the boots on the ground, there were heroes by the thousands,

though they got no glory out of it, or even much recognition from the

folks at home. Korea was a war Americans wanted to forget, even

while it was happening — which is just the kind of war that needs to

be remembered and studied with care. We're in one like it

right now — part of the price a nation pays for forgetting the

grievous mistakes it has made in the past.

It is in the rock, but not in the stone;

It is in the marrow but not in the bone;

It is in the bolster, but not in the bed;

It is not in the living, nor yet in the dead.

This is a riddle, of course. Can you guess the solution?

[From I Saw Esau, edited by Iona and Peter Opie.]

Fear no more the heat o' the sun,

Nor the furious winter's rages;

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta'en thy wages;

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.

Fear no more the frown o' the great;

Thou art past the tyrant's stroke:

Care no more to clothe and eat;

To thee the reed is as the oak:

The sceptre, learning, physic, must

All follow this, and come to dust.

Fear no more the lightning-flash,

Nor the all-dreaded thunder-stone;

Fear not slander, censure rash;

Thou hast finished joy and moan;

All lovers young, all lovers must

Consign to thee, and come to dust.

No exorciser harm thee!

Nor no witchcraft charm thee!

Ghost unlaid forbear thee!

Nothing ill come near thee!

Quiet consummation have;

And renownéd be thy grave!

I've always loved this song, from Cymbeline, one of Shakespeare's late plays, especially this couplet:

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.

It's so

Shakespeare — speaking of the gravest things in the lightest and most

lilting way. I can't help but see it as a reflection of the

country humor Shakespeare grew up with, when hard things, all too

familiar, needed to be tossed off carelessly at times — sort of like

the phrase “he bought the farm.”

At any rate, the tone echoed through English literature — A. E. Housman derived a whole oeuvre from it, as in the following:

With rue my heart is laden

For golden friends I had,

For many a rose-lipped maiden

And many a lightfoot lad.

By brooks too broad for leaping

The lightfoot boys are laid,

The rose-lipped girls are sleeping

In fields where roses fade.

I also love the image in this couplet from Shakespeare's song:

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta'en thy wages . . .

Though

Shakespeare became a wealthy man and a speculator later in his life, he

never got too far, imaginatively, from his working-class roots.

Life to him was always a job of work, literally and

metaphorically. He died soon after giving up his trade as a

playwright — in his heart, I suspect, the end of work and the end of

life were more or less the same thing, as they were for most English country folk of the time.

It took me a while to realize where the image in the couplet above

comes from, specifically — Saint Paul's letter to the Romans, where

the apostle writes, “The wages of sin is death.”

Saint Paul didn't exactly mean that death was a punishment for sin,

or that if you lived a sinless life you could escape death, because no one can live a sinless life. He

was just making a general observation, as Shakespeare was, about the

condition of man, imperfect by nature, doomed to die. When you

take your last wages in this world, all you can buy with them is the

farm.

The Money and the Power: The Making of Las Vegas and Its Hold on America,

by Roger Morris and Sally Denton, Vintage, 2002, is the most important

book ever written about Las Vegas and one of the most important books

ever written about corporate-controlled America in the 20th Century.

The prose can be clunky at times but there are stunning revelations on

almost every page. The result is a clear and impeccably researched

portrait of the criminal/corporate syndicates which run America and the

role Las Vegas has played and plays in their exercise of power.

You can buy it here: