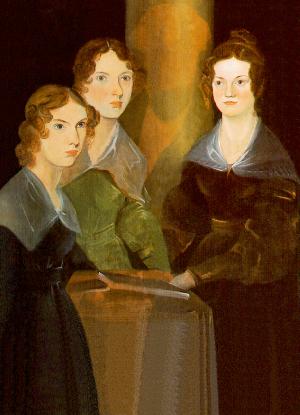

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte (above) is over six hundred pages long, but it’s a page-turner . . . you just can’t put it down. Thackery said that about it when he first read it in 1847 — my experience of it a couple of years ago was no different. Part melodrama, part Gothic thriller, part love story, Jane Eyre is, of all the truly great novels, the most shamelessly entertaining. Wild coincidences, lurid situations, spectacular violence are called upon unselfconsciously to interest and thrill the reader — but nothing in the book is more interesting or more thrilling than Jane herself, Jane’s fearless voice.

The fierceness of the female soul, the subtlety of the female heart, have rarely been so exposed in fiction, and almost never from the inside, as it were — Wuthering Heights by Charlotte’s sister Emily (below, as painted by her brother Branwell) being one other notable exception.

In Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights we eavesdrop on a woman’s

conversation with herself. We do the same, at times, with Tolstoy’s

Natasha and Shakespeare’s Cleopatra — but their creators listen for

what men want to know about them. Jane Eyre tells us what’s important

to her, what she wants us to know.

I suppose it’s not surprising that these two Bronte sisters, who grew up

with their two other siblings in a world of their own among the

desolate moors, a world of imagination and intellect unconstrained by

the conventions of the Victorian patriarchy, should have developed such

singular and courageous voices. (That’s Bramwell’s portrait of his

three sisters, Anne, Emily and Charlotte, above.) And not surprising, either, that their eventual experience of the wider world, where such voices from women

were hardly approved, led to a savage indignation — and a desire to

express it. (Below is a picture of the Bronte family cottage in Haworth by the edge of the moors.)

The love story in Jane Eyre, however fantastical its setting, is the most

penetrating examination of love from a woman’s perspective ever penned.

In Mr. Rochester, Charlotte imagined an ideal man — ideal not because

he was good, or handsome, or gallant . . . but because he looked at

Jane and knew her, recognized at once her power and individuality. And

these things did not frighten Mr. Rochester — they delighted him.

Byron, writing a bit before Charlotte’s time, said of some current flame, “I

would, to be beloved by that woman, build and burn another Troy.” But

Jane would reply, “Before you set to work on Troy, look at me — know

me.” What was Troy to her? What, for that matter, had it been to Helen?

Mr. Rochester talked to Jane. What is more astonishing, he listened to her. That’s what made him her Achilles, her Hector, her Odysseus.

The uncanny thing about the book is that, in between all the Victorian

reticence and circumlocution, Charlotte’s voice sometimes sounds as

clearly and directly as an intimate friend whispering in one’s ear at a

formal ball. The voice is as alive, as frank, as modern, as the voice

of any 21st-Century girl. Jane Eyre is our ever present sister, here

and now — and we have to hope that, like Mr. Rochester, we have the

wisdom and the humanity to listen to what she has to say, and to love

her for the courage it takes her to say it.