This image of a clown is from a 1900 calendar for the Antikamnia Chemical Company. (Thanks to Boing Boing for the link.)

Many people are terrified of clowns — this one can only add to their nightmares.

Category Archives: Circus

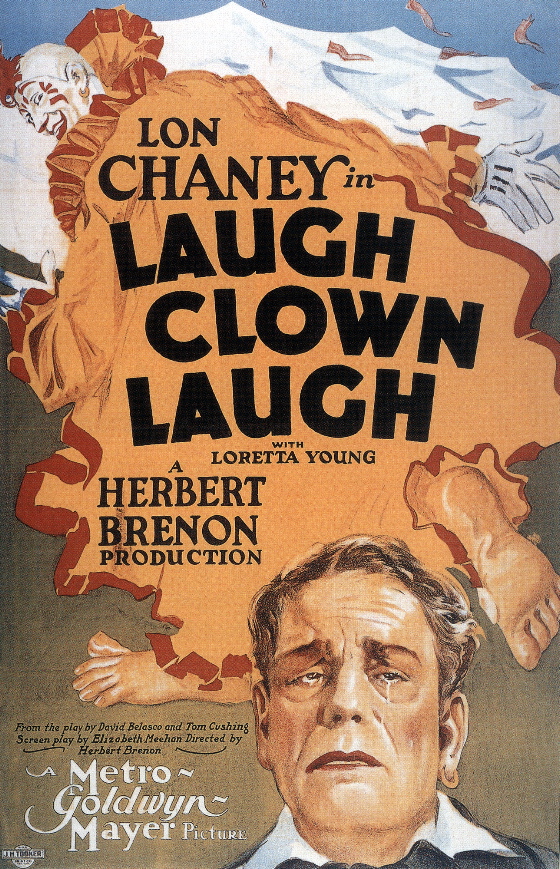

LAUGH, CLOWN, LAUGH

Silent cinema is another country — there’s almost no one left alive who can

visit it except as a stranger. Its narrative language is to the

narrative language of modern films what ancient Greek is to modern

Greek — similar enough to be recognizable and sometimes

comprehensible, different enough to require translation for real

clarity.

As much as we know and read about the silent era, as many silent films as

we watch, entering that lost kingdom always requires an adjustment of

sensibility, a quickening of perception. The landscape retains its

ability to surprise, shock and bewilder.

In The Closing Of the American Mind Alan Bloom argues that we should

study the art of the past not merely for what we may find in it that’s

relevant to our own times, but also for what we may find in it that’s

not — for modes of thought and seeing that depart radically from our

own. This, he argues, gives us a better sense of the conditional nature

of artistic conventions, a deeper appreciation of the many and

strikingly different ways human experience can be processed.

Laugh, Clown, Laugh is a great and powerful film. It is also, by modern

standards, preposterous, over the top, extravagant in ways that can

seem crude to modern eyes. Traditional opera can seem crude in the same

ways to those unaccustomed to its conventions and dramatic methods.

Appreciating a silent film like Laugh, Clown, Laugh requires the same

sort of adjustment of sensibility that an appreciation of The Magic

Flute, as dramatic theater, requires. As a culture, we are inclined to

make such an effort for the sublime music of Mozart — less inclined to

make it for the sublime pantomime of Lon Chaney, the sublime and

delicate imagery of Herbert Brenon.

Without comparing the music of Mozart to the art of Chaney and Brenon, it can still be said that appreciating the latter is worth a great deal of effort, indeed.

Almost everything about Laugh, Clown, Laugh is strange. It is derived from a

stage play and Brenon goes to some lengths to “open up” the play in the

beginning, but narrows the space of the film down to a theater and a

couple of rooms for the extended closing sequences that constitute the

heart of the work, dramatically and visually.

Brenon was considered a major film artist in the Twenties, but the loss of

many of his films makes it hard to evaluate him today, as Richard

Koszarski laments in his brief but intriguing treatment of Brenon in An Evening’s Entertainment. I would add that Brenon had a light

touch, a very subtle eye, which would make his art hard to analyze in

any case. He had the ability to frame shots of great and exaggerated

plastic power, but the real delight of his work, at least in this film,

lies in the simpler visual touches with which he can magically

transform a pictorially ordinary interior scene.

Chaney, with his mastery of pantomime, could effect such a transformation all

on his own, but Loretta Young, who was thirteen when she started

shooting Laugh, Clown, Laugh, had no such technique to draw on. Yet

she carried herself with extraordinary grace, and moved with a

precocious sensuality that is both seductive and disturbing — and

somehow Brenon has managed to capture this physical quality with great

economy and to use it as the basis for what becomes a wondrously

effective performance. From Nils Asther he teases a performance

grounded in an elegant but neurotic way of moving, which skirts the

edge of creepiness with fine calculation.

(It should be pointed out, of course, that the visual style of the film owes much to cinematographer James Wong Howe, with whom Brenon often collaborated.)

The film inhabits the genre of the grotesque — the afflictions of Flik and

the count are exaggerated far beyond naturalism, and Chaney’s

enactments of grief in full clown make-up are surreal and unsettling.

The development of the love triangle involves overtones of pedophilia

and incest, even if these are technically inaccurate terms for what is

going on. The plot tells us that Simonetta has grown up at the end —

but what we see plainly is a child incarnating the persona of a

sexually mature woman, and the spectacle resonates with delirious

perversity.

But as an example of the genre, this one is very mild. There is none of the Grand Guignol which characterizes the ending of He Who Gets Slapped and Chaney has no physical affliction beyond his obsessive weeping.

This is one of those films one might well watch in a mood of exasperation —

annoyed that the story and characters are so stereotyped, so extreme,

so obvious, annoyed that the clichés of the titles are so . . .

clichéd. (“Laugh, clown, laugh . . . even though your heart is

breaking,” reads one, in words that would find their way into the song

written for the film — but not included in the new score composed for

the TCM DVD.)

Yet by the end one might still find oneself seduced by the passionate

commitment of the artists to the tale, ravished by the beauty of the

images and the pantomime, moved by the tragedy — on more than one

level. When Flik asks, “Why should I spoil her youth with my tears?” he

is speaking not only as a man but as an artist. There is a physical,

aesthetic contrast between Flik and Simonetta when they pose as a

couple which the artist in Flik may well find as disturbing as we do.

In the lost kingdom of silent cinema, this is not a superficial

contrast — it conveys a dramatic, emotional, spiritual message,

through characters who, like the characters in a story ballet, move the

way they move because they are who they are, and are who they are

because they move the way they move.

The film is available on DVD as part of the Turner Classic Movies

set The Lon Chaney Collection. Michael F. Blake’s commentary is excellent, as is the original score by H. Scott Salinas. It emphasizes the sentiment of the story without apology but is lively and inventive and sensitive to the shifting moods of the film.

HE WHO GETS SLAPPED

As art forms go, the silent feature evolved with lightning speed. Barely two decades passed between the commercial inauguration of film as a peepshow attraction and the magisterial eloquence of The Birth Of A Nation. Less than fifteen years after that the silent feature was gone, apart from what Donald Crafton has called the pyrrhic victory of

Chaplin’s sound-era silents.

The speed of its evolution and the brief span of its dominance meant that it was always a medium in transition. One of the excitements, and sometimes one of the frustrations, of watching silent films is the frequent collision of artistic strategies within a single work. He Who Gets Slapped is a perfect illustration of the phenomenon.

First, you have the play on which it is based — an apparently serious lyric tragedy of the sort that would have perhaps struck readers of the old Saturday Evening Post as highbrow. Derived from this you have the film scenario itself, a wonderfully preposterous and unapologetic piece of Grand Guignol, in the best Theater of Blood tradition. And then you have director Victor Seastrom’s treatment of this scenario, an exaggerated and stylized but basically straightforward narrative presentation of the Grand Guignol element, interspersed with metaphorical visual interludes designed to remind us of the work’s

original pretensions.

Finally, at the center of it all, unifying if not quite synthesizing the disparate elements, you have the very great plastic art of Lon Chaney, supported by several other players — Norma Shearer, John Gilbert and Tully Marshall in particular — who can inhabit the world of Chaney’s eloquent pantomime.

It’s the power and force, the unprecedented aesthetic phenomenon, of a great

silent film actor like Chaney which by its nature confounds the conventional artistic strategies of the piece. The flowery poetic intertitles, which I suspect derive from the play, and the interpolated visual metaphors, are so inferior to Chaney’s performance that they stop the narrative dead. They seem to be apologizing for the sensational nature of the story, the outrageousness of the purely narrative images.

But the purely narrative images are astonishing and fine, pushing an apparent naturalism just a little too far — into the demented dreamscape of the story itself. The odd, mournful swaying of the clowns’ dance, the fantastic dappled sunlight of the Gilbert-Shearer picnic, even the obviously faked inserts of Gilbert and Shearer “riding” the horse, achieve a perfect balance between plastic beauty and a coherent representation of a convincing screen place.

There have been other arts which, in times of rapid transition, displayed this same sort of aesthetic discombobulation. Titus Andronicus, for example, mixes the brutal, grotesque vision of Marlowe with the more ambiguous and humane treatment of character with which Shakespeare would eventually modify Marlowe’s great innovations in theatrical form.

But not yet having internalized Marlowe’s lessons, Shakespeare simply apes Marlowe’s shock tactics and tries to present them in his own voice. The result is disconcerting and perpetually strange.

Seastrom’s arty gloss on the great cinematic achievement that lies at the core of He Who Gets Slapped has the same flavor of insecurity — of lessons not yet internalized, of forces not yet appreciated. John Huston once told James Agee that film can’t be used metaphorically, since filmed reality is by its nature already a metaphor. There is something in Lon Chaney’s eyes, in the way he moves under that clown make-up and clown costume, which is beyond the range of literary expression, beyond the range of metaphor. “He” is a dream image — and dreams always get diminished by conscious interpretation.

[Above is the principal cast and crew of He Who Gets Slapped — that’s Seastrom in the vest and bow tie standing between Shearer and Gilbert.]

AMY CREHORE

Check out the art of Amy Crehore, who makes delicious images that combine the sang-froid of Magritte with the innocence of antique vernacular icons and the insinuating eroticism of a high-class Parisian strip show from the Twenties:

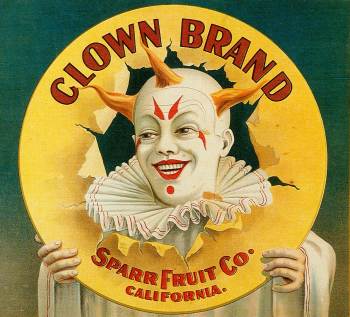

She also has a blog filled with curious images and objects that clearly nourish her strange imagination, like the wondrous fruit crate label below:

Her blog: