Gun Crazy, 1950.

Click on the image to enlarge.

My hatred of modern-day “L. A.” (as some people like to call it) is equaled only by my love of Los Angeles (with a hard ‘g’ please) before my time, the 1950s and earlier.

From Bryan Castañeda comes a link to the wonderful footage above, apparently filmed to be used as process shots for the 1948 movie Shockproof, directed by Douglas Sirk.

In the early days of cinema, itinerant cameramen would have collected footage like this as “actualities” for exhibition to audiences spellbound by the sheer beauty and fascination of tracking shots depicting their own or distant cities. By 1948, the spell of such shots was broken, at least as a stand-alone commercial product, relegated to material for back-screen projections, but the footage recorded is just as beautiful and fascinating as that collected by the cinematographers of the Edwardian era.

Click on the image for a larger view.

And here’s a link to my review of this terrific film — The Big Combo.

. . . to think about Jane Greer, coming out of the sun into La Mar Azul.

Although it has its defenders (Johnathan Rosenbaum among them), Nicholas Ray's 1958 film Party Girl hasn't got nearly the reputation it deserves. On the surface it has a familiar plot — a mob lawyer motivated by love to break free of his past — and it's a period film, set in gangland Chicago in the 1930s. It's shot in Cinemascope and Metrocolor. For all that, it's pure Fifties, and very noir. In traditional movies with the same theme, even Polonsky's dark Force Of Evil, a decent world is waiting to embrace the repentant mobster. In Ray's film, as in all real noirs, things aren't so simple. The cops are bunglers, the moral lines are always blurred — at the climax, the hero makes a last desperate attempt to save himself and his true love with yet another phoney lawyer's trick, just like the ones he used to save guilty thugs from justice.

The tone of the whole film is brutal, cynical — the world it depicts is a maze with no center, no escape . . . except one, the love of a good woman. The good woman, contrary to the conventional wisdom, is a recurring type in films noirs — almost as common as the femme fatale. We find her in classic noirs like The Dark Corner and Ray's own On Dangerous Ground — a force of salvation for the boxed-in, royally fucked male protagonist. In this film, Cyd Charisse's good girl is not so good — she's as cynical and lost as Robert Taylor's corrupt lawyer. The role is a perfect fit for Charisse's slightly opaque screen persona, and a perfect match for Taylor, who can be equally opaque.

Their somewhat wooden styles, as Rosenbaum points out, have never been put to better use dramatically. It's actually touching when they recognize each other as kindred spirits — people in whom the flames of hope and passion have been all but extinguished. Their psychic wounds are mirrored in recurring images of physical disfigurement — in Taylor's slightly crippled leg, in the threat of using acid to mar the mask-like beauty of Charisse's face.

The Metrocolor isn't used for glamor. The colors are garish, lurid, sometimes deranged. The film was produced by Joe Pasternak, who usually handled musicals at MGM. Charisse, who plays a showgirl, is given a couple of production numbers that look like the covers of Les Baxter LPs come to life. The choreography is crude but shows off Charisse's icy erotic quality to great effect — the numbers are almost like parodies of Minnelli's exotic style.

Ray uses Cinemascope brilliantly, with lots of subtle camera moves that quietly direct our attention to action unfolding within the wide frame. There's a powerful gangland rub-out montage that almost certainly influenced the one at the end of Coppola's The Godfather. There are first-rate performances in supporting roles by Lee J. Cobb and John Ireland.

It's a great film, one of Ray's best, and is now available on DVD for the first time through the Warner Archive. Fans of Ray and of film noir in its last, Baroque phase (best exemplified by Welles's Touch Of Evil) shouldn't miss it.

Tony D'Ambra, creator of the ever-useful and ever-interesting films noir blog has decided to call it a day — he's rolling down the Venentian blinds on the site, pocketing his revolver, lighting a cigarette and stepping out into the dark streets to meet his fate alone.

Even though there will be no new posts, I'm hoping he'll keep the archived content online, and the link to his site, over there on the right, will stay up as long as he does.

Tony made invaluable contributions to my own thoughts about the noir tradition, for which I will always be grateful. His footsteps on the wet pavement, between the pools of reflected neon light, will always echo in my mind.

Matt Barry over at The Art and Culture Of Movies has recently posted an insightful short review of Orson Welles's Touch Of Evil. He calls it an unnerving film, which it certainly is, but points out that one of its most unnerving aspects is the way Welles goofs on our expectations of what a gritty little film noir should be.

The film's extreme stylization both seduces us into its nightmare world and distances us from it as an aesthetic creation, all at the same time. Touch Of Evil was not quite the last classic noir — I think you'd have to give that distinction to Odds Against Tomorrow, which came out a bit later — but its self-consciousness about the form was a sure signal that the tradition had all but played itself out. One definition of a neo-noir is that it's at least as concerned with commenting on the form as with working inside it. In some ways, Touch Of Evil was the first of the neo-noirs.

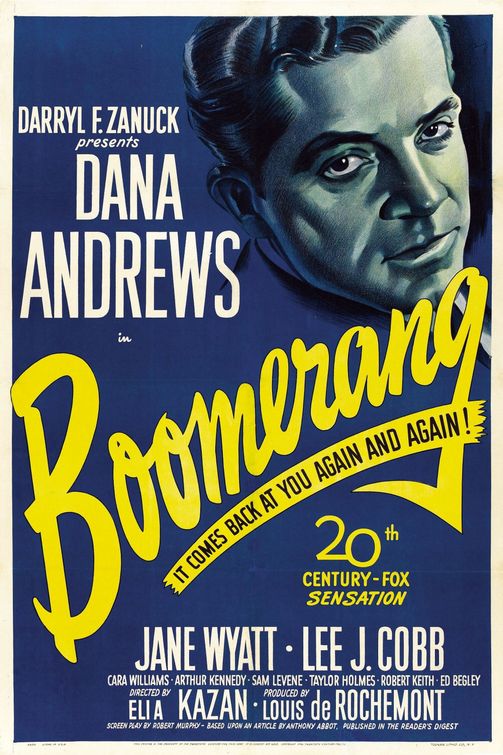

Ivan Shreve over at the ever wise and amusing Thrilling Days Of Yesteryear writes, “The argument over whether or not Boomerang! is a legitimate film noir will rage on until eternity.” Of course it will. Arguments about what films are or are not noir are almost always irrational and thus can never be settled in any reasonable way.

The general idea is to parse any film made in Hollywood in the 1940s and 1950s searching for reasons to call it noir. The use of shadows, the element of crime in the plot, any suggestion of moral ambiguity or darkness in the characters is usually enough to qualify a film for the designation. The truth is that film noir is no longer a descriptive or analytic term but one of approbation — it means “a film which is cool, a film I like”. Sometimes it just means an old film in black-and-white which isn't a comedy or musical.

It would be far more logical to ask a simple question up front — is there some other established genre or tradition into which a particular film fits? If there is, there's no conceivable reason to tag it as a noir. Doing that just makes film noir a term so vague as to have no real meaning at all.

As it happens, Boomerang! fits nicely into a very distinct tradition usually called docu-noir. The tradition was virtually invented by Louis de Rochemont, who happens to be the producer of Boomerang! De Rochemont made his name producing the March Of Time newsreel series, essentially a breezier and more entertaining variant of the standard newsreel. He then became a producer of features at Fox. His first film, the docu-noir The House On 92nd Street, set the pattern for the new form.

Docu-noirs were police or government-agency (or sometimes newspaper) procedurals, usually based on real events and filmed in a quasi-documentary style, often in the locations where the real events occurred. Although they dealt with the same post-war anxieties that fueled the classic films noirs, they were radically different kinds of films, because they took the point of view of the authorities and they insisted that the official institutions of society could combat society's ills.

[Caution, plot spoilers ahead . . .]

The protagonist of a docu-noir might encounter corruption within the institution he served, but his personal integrity was always a match for it and allowed him to ensure that justice was done in the end. There was often, as in Boomerang!, a subsidiary character (played by Arthur Kennedy, above, in this case) who resembled the protagonist of a classic noir, an innocent man wrongly accused, dragged down by fate or official misconduct, but we never saw the story through his eyes — we saw it through the eyes of the official (or dogged reporter) who would save him.

There are no such saviors in classic noirs — the whole burden of which is to involve us emotionally in the nightmare of the trapped man, to show us the world from his point of view, to make us feel its oppressive weight. The protagonist of a classic noir might or might not survive his nightmare, but such salvation as he occasionally does find is likely to be provisional — there is rarely any suggestion that the world which generated his nightmare is ever going to change.

This is light years away, existentially, from a film like Boomerang!, where the hero has a dark night of the soul, chooses to do the right thing, defies the corruption of his bosses, frees the innocent man and goes on to become the Attorney General of the United States. It is, in short, a film which questions and criticizes but ultimately vindicates the American legal system, affirming the efficacy and ultimate triumph of moral action within it. If Boomerang! is a film noir then I guess Mr. Smith Goes To Washington is a film noir, too, and we need some other term to describe movies like Detour, Out Of the Past and Thieves Like Us.