I've just updated the links in the Film Reviews A-Z section (to the left) — which now covers 114 films. The Film Noir Master List has also been updated to incorporate some recently viewed titles.

Check them out.

I've just updated the links in the Film Reviews A-Z section (to the left) — which now covers 114 films. The Film Noir Master List has also been updated to incorporate some recently viewed titles.

Check them out.

It's sometimes noted, quite correctly, that the artists who made what we now think of as the classic films noirs were entirely unfamiliar with the term, and indeed had no conception that they were working in a distinct tradition. They thought of the movies they were making as crime thrillers.

This is occasionally cited in support of the idea that the term film noir is a category created by cinéastes after the fact, and therefore inauthentic, misleading. It certainly was created (or at least popularized) by cinéastes after the fact, but that doesn't mean it's inauthentic or misleading. Such a view fails to take into account how genres and traditions arise, which is a complex process — a combination of historical and cultural trends, influence and imitation among artists, and simple commercial calculation. All these factors can combine to create distinct new forms, and in the case of film noir I think they did.

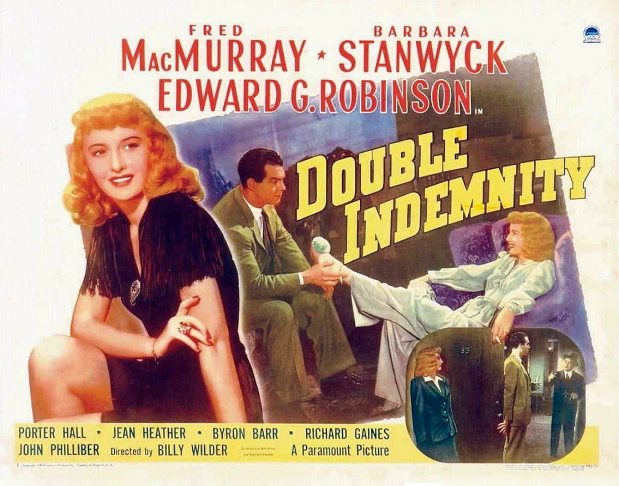

Two early films, which I would not call films noirs, nevertheless set the tone for the new form — The Maltese Falcon and Double Indemnity. The Maltese Falcon was a fairly standard work of hardboiled detective fiction but it had a twist. In hardboiled detective fiction, the world might be a dark and messy place, but the detective had a code of honor which made a kind of grim moral sense amidst the darkness and the mess.

Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon had such a code and he stuck by it — but Huston allowed him more than a trace of doubt as to whether the code had any ultimate meaning, any ultimate value. This was something new in the crime thriller, in hardboiled detective fiction — this hint of existential uncertainty.

In Double Indemnity, essentially a domestic murder melodrama, Billy Wilder offered a portrait of middle-class American life that was unremitting in its bleakness, its moral vacuousness. I'm not sure that Wilder had any particular message to convey by this — he just sensed that in the midst of the global horror of WWII audiences were looking for sterner stuff in their melodramas, a darker vision of ordinary life that would accord with the experience of civilization as a whole gone suddenly mad.

Both films were commercially successful — proof that audiences were at the very least receptive to darker visions, to stories that raised the most disturbing (and unresolved) questions about morality and society. Both films were also well-received critically. This gave other film artists a kind of permission to experiment with similar themes — within the confines of the crime thriller. They got very creative within those confines after WWII, when a generation of men scarred by war came home, and when the specter of nuclear annihilation became a reality for everyone.

They didn't think, “We're going to create a new kind of existentially challenging crime thriller.” They just inflected the crime thriller with a new mood. Audiences responded, and formulas began to solidify. Film artists imitated each other, got turned on by each other's work. Elements that worked in one film got incorporated into other films, given new twists. It was a combination of playing it safe commercially but also pushing things as far as they could go within familiar territory — testing how much darkness the public really wanted.

It turned out to be quite a lot — so much so that that during the Fifties filmmakers began to realize that the darker themes could be incorporated into other genres besides the crime thriller, as they were, for example, in the domestic melodramas of Sirk, in the Westerns of Ford and Mann. When that happened, the classic film noir more or less played itself out. Its usefulness as a cultural escape valve had ended. Any kind of film in the Sixties could deal with existential angst, with moral bewilderment, with political or social criticism, in more direct terms. America had internalized the darkness of the film noir — the resulting culture wars were just a matter of time.

Film noir had a beginning in the global dislocations and moral derangement of WWII, and an end in the open social and political critiques of the Sixties. There had never been anything quite like film noir before WWII, and there has never been anything quite like it since the Sixties. It was, and remains, a distinct tradition.

[With thanks to Tony D'Ambra at films noir for some thoughts that provoked the above meditation . . .]

This

extraordinary film is, generically, a late-cycle crime melodrama, but

it's quirky and original enough to transcend the genre pretty

thoroughly. John Garfield plays a crooked Wall Street lawyer who

crosses the line between representing organized crime figures and

collaborating with them. Like the great Warner Brothers gangsters

of the 30s, he's a tough guy on the make who chooses a life of crime,

but he thinks it's going to be “respectable”, white-collar crime — until he's dragged

into the violence and thuggery that underpins the rackets he believes he

can manipulate.

This distinguishes him from the gangsters of the 30s, gives him a kind

of innocence, though it's innocence of a curious sort. He and a number of

the film's characters make a distinction in their minds between

“honest”, harmless criminality, mere corruption, and the “evil”

criminality of men who resort to violence. This takes us very

close to the territory of the true film noir, where all of society has lost its moral bearings, where the lines between right and wrong have been hopelessly obscured.

Abraham Polonsky, who directed and co-wrote the film, is not quite venturing into that territory, however. His outlook is more political — less concerned with moral bewilderment and confusion than with the wholesale structural corruption

of American society.

The lines between good and bad are ultimately very clear in Polonsky's universe,

and he posits off-screen forces that are gathering to fight the

corruption of the system, forces which Garfield's character will eventually decide to join.

The protagonist of a true film noir

never has this route out of his predicament. His plight has more to do with

existential uncertainty than with political or social problems in

need of practical reform. At the same time, though, Force Of Evil is

suffused with the atmosphere of a true noir,

since the forces of good are never personified dramatically — the

crusading special prosecutor Garfield finally turns to never appears on

screen.

Force Of Evil points the way to Coppola's Godfather films, which, like this one, are in the gangster tradition but with a crucial twist — they concentrate not on the

battle between good guys and bad guys but on the creeping moral decay of the bad

guys, seen from their point of view.

We don't revel in the

transgressive behavior of Garfield's character, or of Michael Corleone

in the Godfather films, as we

reveled in the transgressive behavior of Cagney's bad guys, in

confident expectation that they will be brought to justice in the end. Garfield's character in Force Of Evil,

like Michael Corleone, is punished by forces within himself and close

to home. Far from going down in a blaze of outlaw glory, he rots

from the inside, slowly. Polonsky offers Garfield's character a

way out, through social action and personal reform — Coppola, less

political, less didactic, less optimistic perhaps about American society, offers Michael Corleone nothing.

Fox home video has been releasing a lot of terrific DVDs in their Fox Film Noir

series — great transfers of entertaining films with generally

excellent commentaries and brief featurettes about the movies and their

creators. They're running out of films from their vaults which

can plausibly be called noir — except that these days, apparently, just about anything can plausibly be called noir.

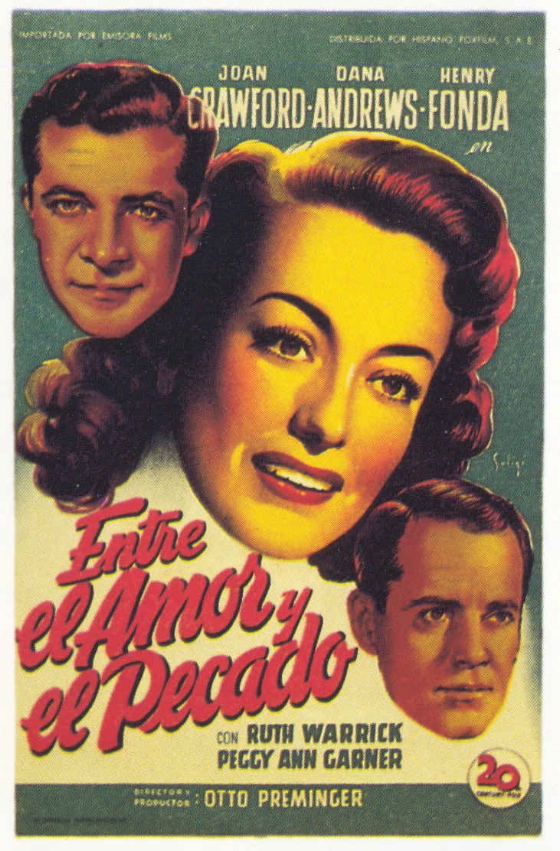

Daisy Kenyon, the 23rd title in

the series, is an extremely interesting film by Otto Preminger from

1947 which could plausibly be called domestic noir,

though it doesn't involve crime or violence in any significant

way. It's basically a soap opera centering on a very complicated

love triangle, but it's disturbingly dark, in ways that wouldn't have been

conceivable in Hollywood before WWII.

Joan Crawford plays a career girl in New York who's having an affair

with a married man, played by Dana Andrews, a charming self-centered

lout. Neither character seems to feel any moral qualms about the

affair, and Preminger presents it with an almost cynical nonchalance

that's strikingly adult and modern.

Crawford meets an equally charming but somewhat unstable returning war

vet, played by Henry Fonda. Fonda's character feels that the

world and everyone in it has become dead, and isn't sure if this

feeling has to do with the loss of his wife in a car accident or with

his experiences in combat. The war, and its collateral moral damage, are also referenced in an off-screen subplot in which

the Andrews character defends a Nisei war vet whose farm was stolen

from him while he was off fighting for his country, heroically, in

Italy. He loses the case.

According to Preminger's biographer Foster Hirsch, these elements

were not prominent in the novel on which the film was based. It

was Preminger and his

screenwriter who chose to associate the moral confusions and neuroses

of the characters with the broader anxieties of post-war American

society, issues of guilt over the price of victory, over the

psychological wounds suffered by the soldiers who won that

victory. It's a theme one finds

in many noir and noir-inflected films of the time, sometimes explored explicitly, as it is here, sometimes only by implication.

Perhaps Preminger was too explicit. Daisy Kenyon

was a box-office disappointment. Without the cover of the

crime-thriller genre, elements of which figure to one degree or another

in most other domestic noirs, the film's investigation of post-war American angst may have cut too close to the bone for contemporary audiences.

The mood of the film is almost unbearably tense and unsettling,

eventually involving child abuse and a scandalous divorce trial played

out in the tabloid press. There had always been soap operas like

this in American movies, of course, but there was always a clear sense

of when moral boundaries were being crossed and what the consequences

would be. Daisy Kenyon plays out in a world in which moral boundaries seem to have been erased.

The Spanish title of the film translates as “between love and sin”

but the tale offers few clues as to where one stops and the other

begins. The romantic triangle is resolved at the end, more or

less, with everyone doing the “right” thing — but there's hardly a

sense of moral triumph. We feel that all the characters are going

to remain adrift in a morally ambiguous universe, trying to walk a line

that none of them can see clearly. This is noir territory, all

right, but strictly domestic, and explored primarily from the point of

view of the female protagonist, which distinguishes it from the classic

noir cycle.

Volume 4 of Warner's Film Noir Classic Collection

is currently on sale for $29.99 all-in from Amazon — no sales tax, of course, and no

shipping charges (if you choose Super Saver Shipping). Ten films,

all interesting, including several noir classics and one masterpiece, They Live By Night — for less than $3 a film. Entertainment doesn't get much cheaper than this.

There's a terrific short review of Fritz Lang's Clash By Night, maybe the greatest of all domestic noirs, recently posted on the web site films noir. It has this sublime evocation of the film's themes — “Sexual abandon and existential entitlement are put on trial and found empty.”

Double Indemnity and Sunset Boulevard are certainly the most entertaining domestic noirs, but Clash By Night offers far more complex insights into the ways post-WWII anxiety corroded relations between the sexes.

Check out the review here.

This film by Fritz Lang, from 1945, is essentially domestic noir — the story of an unhappy, ordinary middle-aged married man led into a life of deception and, ultimately, crime by a fetching femme fatale.

It was Lang's favorite among the films he made in America and has a

considerable reputation but I find it curiously dead emotionally and

lacking in real suspense.

The problem is that the fatal femme

is so obviously on the make, so obviously not attracted to the ordinary

man, so cynical and so dumb, that we feel only pity for the guy, a pity

laced with scorn. We can see what attracts Walter to Phyllis in Double Indemnity

— the two are hot together — and even if we suspect that Phyllis

might be using Walter, part of us thinks it might be worth getting used

by a woman like this. This implicates us morally and emotionally

in Walter's transgressions, makes us care about his fate.

It's impossible to care about Chris in Scarlet Street

on that level — watching his life come apart at the seams is like

watching a train wreck from a distance. It's fascinating and

horrifying but we're not involved. In Double Indemnity, like it or not, we're passengers on that trolley hurtling towards the end of the line.

The ending of Scarlet Street

achieves a kind of tragic power, because things go so horribly

wrong, and Chris's moral collapse is so complete and so bleak.

It's not a genuine tragedy, though, because in a genuine tragedy we

could imagine ourselves in Chris's place. In Scarlet Street we're denied that identification, that implication in his fate.

Although, as I wrote earlier, I don't see film noir

as expressly concerned with theological issues, there is a

sense in which the idea of “the death of God”, as a kind of

metaphorical expression for existential bewilderment, gets close to the

heart of the tradition.

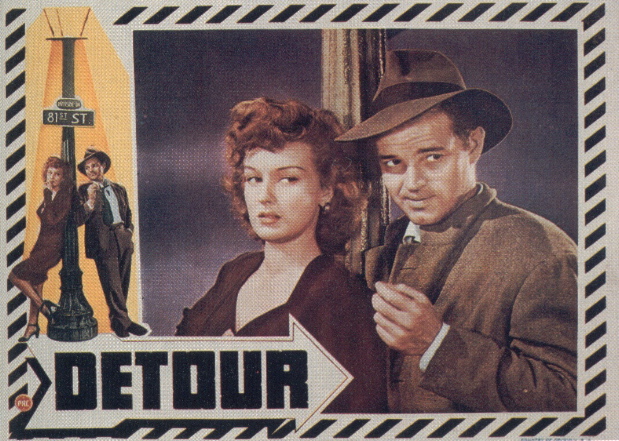

Edgar G. Ulmer's Detour, a low-budget thriller from 1945, was arguably the first true film noir.

It offered a vision of the world as a moral maze from which there was

no exit — an image that accorded well with the unconscious dread which

gripped America in the wake of WWII and in the shadow of nuclear

apocalypse.

In this light, it's interesting to look at Ulmer's The Black Cat,

a strange Universal “horror film” from the early 30s. There, the

source of the horror that ensnares its innocent protagonists is a

modernistic version of the old dark house — which sits on the site of a

ghastly battle from WWI, somehow infected by the mass slaughter that

took place there.

This may not be enough to prove that Ulmer saw a connection between the moral chaos of Detour and the horrors of WWII but it certainly suggests

that there may have been an unconscious association of the two

ideas in Ulmer's mind.

Certain modern commentators want to see film noir

as a phenomenon with essentially political implications — something

that's not hard to argue given the leftist leanings of many of the

great masters of the noir tradition, a number of whom were eventually blacklisted. But seeing film noir

as essentially political expression I think sells the phenomenon short. Film noir reflected

an existential dread far deeper than politics could encompass.

“The death of God” gets closer to expressing this than “the corruption

of Capitalism”.

Curiously enough, the French critic Luc Mollet said that Ulmer's whole body of work

expressed “the loneliness of man without God”. A recent essay on

Jules Dassin's Brute Force, included in Criterion's DVD edition of the film,

quotes Mollet dismissively and ironically, suggesting that he was just

offering a kind of smokescreen for the political underpinnings of the noir vision. But I think it makes more sense to see the nutty, irrational Stalinism of many noir

filmmakers as a smokescreen for the more comprehensive psychic

dislocations of post-WWII America, in which Communism and Stalinism

were just faddish, ill-conceived replacements for a God who seemed to

have abandoned the world in the desert outside Los Alamos, New Mexico,

after clearly announcing, at places like Auschwitz, his plans to retire

permanently from the world's affairs.

If film noir were simply a

reflection of the politics of its leftward-leaning makers, it ought to

be terribly dated today, after the demystification of Communism and

Stalin, those ephemeral shibboleths for which the Hollywood radicals martyred

themselves. But film noir

still speaks to us as strongly as it ever did — perhaps because “the

loneliness of man without God” still troubles the spirit, while the

passing of Stalin and Communism go conspicuously unlamented.

[Thanks again to Tony D'Ambra of films noir whose posts on film noir and the death of God prompted the thoughts above — and to Michael Mills' classic film blog for the Detour advertising art.]

In

a comment here (and currently on his own web site films noir) Tony

D'Ambra posts an intriguing quote from Mark Conrad about the connection

between film noir and existentialism:

“My proposal, then, is that noir can also be seen as a sensibility or

worldview which results from the death of God, and thus that film noir

is a type of American artistic response to, or recognition of, this

seismic shift in our understanding of the world. This is why Porfirio

is right in pointing out the similarities between the noir sensibility

and the existentialist view of life and human existence. Though they

are not exactly the same thing, they are both reactions, however

explicit and conscious, to the same realization of the loss of value

and meaning in our lives.”

[This is from Conrad's book The Philosophy of Film Noir: Nietzsche and the Meaning of Noir: Movies and the ‘Death of God’.]

I agree with the gist of the quote, and with Tony's assertion that film noir

and existentialism have a lot in common — though I'm not sure

that there was a direct influence on the former by the latter. I

think Conrad is on the right track when he locates the essence of film noir in a particular moral orientation to the universe and not in a style or in subject matter.

I'm also not sure that the death of God is quite the right way to explain film noir, though — except as a metaphor for “the loss of value and meaning in our lives”. Film noir,

to me, is more about moral bewilderment as a social phenomenon, with

social causes, than about loss of faith in God. It's about male

insecurity and fear of women, about a creeping dread that the world

isn't what it seems to be, doesn't work anymore — if it ever did.

These sorts of feelings have theological implications of course, but

they don't lead automatically to atheism or to existentialism — not in America, with its

strong Protestant tradition, which has always preached what the

theologian Paul Zahl calls a “low anthropology”, holding that the world

is intrinsically corrupt, redeemable only by supernatural Grace.

Hitchcock's The Wrong Man is an apt illustration of what I mean. The film is pure noir

— except in its denouement, when the protagonist is saved not by a

good woman or luck or some kind of desperate action but by the direct

intervention of Jesus. This is not a whole lot more improbable

than the ways some other protagonists get saved in the film noir tradition.

We needn't go this deep, however, to find the core, and the enduring appeal, of film noir.

The feelings it deals with, though brought to the surface by the

peculiarly horrific experiences of the generation that suffered through

WWII and afterwards lived in the shadow of nuclear annihilation, are

common to all men and women at some moments of their lives.

Such feelings may lead to atheism, to philosophies like existentialism

— or to religious epiphanies like the one Saul had on the road to Damascus. Because film noir

is art, not theology or philosophy, it is not concerned with such

outcomes. It is only concerned with the feelings, with certain particular conditions of the heart — with bringing

them to the surface and allowing us to engage them.

In my last post I quoted James Ellroy's brilliant summation of the message of film noir — “You're fucked.” One of the ways “you're fucked” in film noir is that most of the women you're going to meet in the shadowy backstreets of noir's

dark city are going to be smarter and stronger than you are. They

may use their power to save you, they may use it to destroy you, but

the situation is going to be beyond your control.

This view of women was obviously a projection of male anxiety and

insecurity in the post-WWII era. There are some extraordinary

female characters in the film noir

tradition, but usually they're not quite real — they are demons, or angels,

summoned up out of troubled male psyches. A film doesn't need a femme fatale to be noir

— they're absent in many classic films in the tradition — but it does

need a sense of male helplessness. It's a comprehensive

helplessness, in the face of society and the universe itself — tough,

powerful women are just one manifestation of a general existential

dread.

When the situation is looked at from the woman's point of view, we leave the territory of noir

— move into another tradition, typically that of the psychological

suspense thriller, of the Hitchcockian variety, which is often

presented from the viewpoint of the female, with whom we

identify. This tradition predated noir and is in fact connected to works of Victorian Gothic fiction, such as Jane Eyre.

It deals with more traditional female anxieties arising out of the

contradictions of an insecure patriarchy. To me it makes no sense

to call this sort of movie film noir, even though it may tap into the same mood of existential dread that pervades the classic noir.

As I've observed before, it took the neo-noir Chinatown to look back on the noir

tradition and try to imagine the effect of its male insecurities on

women — but this was never really a conscious concern of classic film noir.

In my last post I wrote:

I would argue that pulp fiction, hardboiled fiction, from the

20s and 30s is something different from the wartime and post-war films that are, to me at least, the heart of the film noir tradition. Film noir

drew on that fiction, just as it drew on the 30s-era crime melodrama

and conventional detective fiction, but it became something new.

So what was new about it?

James Ellroy summed it up best when he observed that the basic message of film noir

is “You're fucked.” It's an existential message, philosophical

(or perhaps theological) in nature. Another way of putting it

might be “The world is fucked, at its core, and there's nothing you can

do about it.” You might temporarily survive the predicament this

puts you in, or it might destroy you, but the predicament isn't going

to change.

This represents a profound divergence from the traditional “hero's

journey”, in which an everyman faces tests and ordeals in the pursuit

of wisdom, of meaning. It also represents a divergence from the

“outlaw ballad” tradition of the 30s-era crime melodrama, in which we

explore the underworld and revel in the transgressive behavior of

society's rebels — all the while confidently expecting the rebel's

death and a reassertion of humane values. In true noir, those traditional values have evaporated.

You have to ask yourself why such a radical divergence from earlier

traditions happened in the post-WWII era, and the answer to me is

obvious. The basic message of war, and particularly of combat, is

“You're fucked.” The soul-shaking experience of hearing this

message delivered in the most brutal terms doesn't go away after the

war ends, even if it ends in victory. It is not subsumed in

feelings of patriotism or in the satisfaction of having done one's duty.

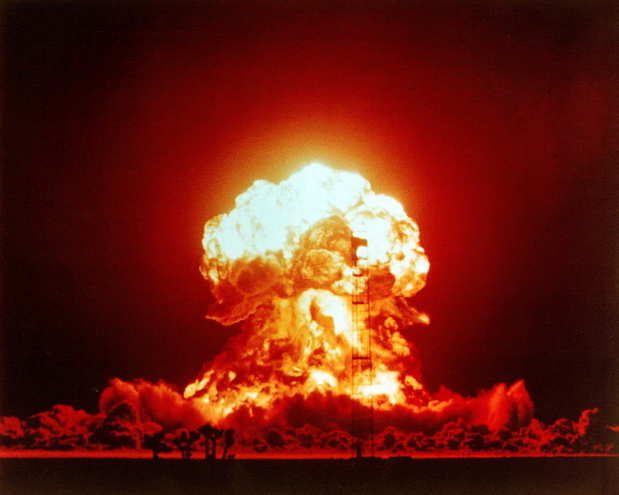

It endures forever. In the case of WWII it had a macabre

objective correlative — the atomic bomb, the image of the mushroom

cloud, which summed up the enduring sense of existential dread that had

infected American society, and in particular its returning war vets.

Film noir was an arena in

which that existential dread could be engaged safely — and there was

something exhilarating about the exercise, the exhilaration of dealing

with an urgent but buried anxiety. The existential dread I'm

speaking of here didn't define post-war America but it was there, and

it couldn't be talked about directly in a world that was desperately

trying to get back to normal. But it could be faced in art — most especially in film noir.

Tony

D'Ambra of the ever useful films noir web site posted an interesting

comment about my Film Noir Master List which I'm eager to respond to:

Tony wrote:

I doubt you will welcome this comment, but here goes.

I'm delighted by all thoughtful comments!

He continued:

I don't see the point of your classification system: it has meaning for

you only and no film can ever be categorised to such a degree.

I realize that my list violates convention, but others have found it

useful, if only as a provocation to further thinking about the

subject. It's primarily intended to provoke a new conversation about film noir, which in my opinion has gotten to be such a vague term that it's losing its usefulness.

And Tony wrote:

For example, there is wide agreement that Wilder's Double Indemnity

is an elemental film noir, yet you describe it as a “domestic noir”?

Neff is an unmarried loner and Phyllis an amoral gold-digger whose

marriage was a sham from day one, so how does domesticity gone bad come

into it? There is “no moral confusion” or “existential dread”: both

protagonists are motivated by greed and each has no scruples when it

comes to making sure that only one of them makes it to the end of the

line. Marriage has nothing to do with the dramatic imperative of the

plot. Remember Phyllis murdered Dietrichsen's first wife, so she could

marry him for his money. Neff was ready to be seduced and she knew it:

this is the essence of the noir paradigm of the femme fatale, which has

little to do, if it ever to did, with the role of woman in WW2 and its

aftermath. Remember, the great noir novels by Hammett and Cain, were

written before WW2.

Domestic noir, to me, from Double Indemnity to Sunset Boulevard,

is characterized primarily by a rancid view of domestic life, and

especially married life. It's not about good marriages gone bad

— instead it reflects a jaundiced view of the domestic realm, sees it

as corrupt, no longer viable, infected by the moral chaos, the

existential bewilderment, of the wartime and post-war world.

Double Indemnity takes place primarily in middle-class homes and offices — not in the typical urban jungle of the classic noir, the labyrinth of the dark city. In the domestic noir, the existential dread symbolized by noir's dark city has penetrated the “normal” world, transformed

it. Both traditions are dealing with the same existential dread,

but viewing it from different angles — different enough to constitute

two distinct traditions.

Phyllis Dietrichsen is indeed a femme fatale, one of the most fatale in all of movies, but the presence of a femme fatale doesn't automatically make a film noir, anymore than the lack of one excludes it from the category. The femme fatale in the person of the vamp was a staple of silent cinema, featured in films we would never think of calling noir, and many classic films noirs have heroines who save the protagonist.

Finally, I would argue that pulp fiction, hardboiled fiction, from the

20s and 30s is something different from the wartime and post-war films that are, to me at least, the heart of the film noir tradition. Film noir

drew on that fiction, just as it drew on the 30s-era crime melodrama

and conventional detective fiction, but it became something new.

My underlying argument in all this is that we lose sight of what made film noir

new and distinct when we confuse it with its antecedents and with other

films that were dealing with the same cultural anxieties in different

ways and in different contexts.

Through

the good offices of Joe D'Augustine, of the excellent Film Forno web

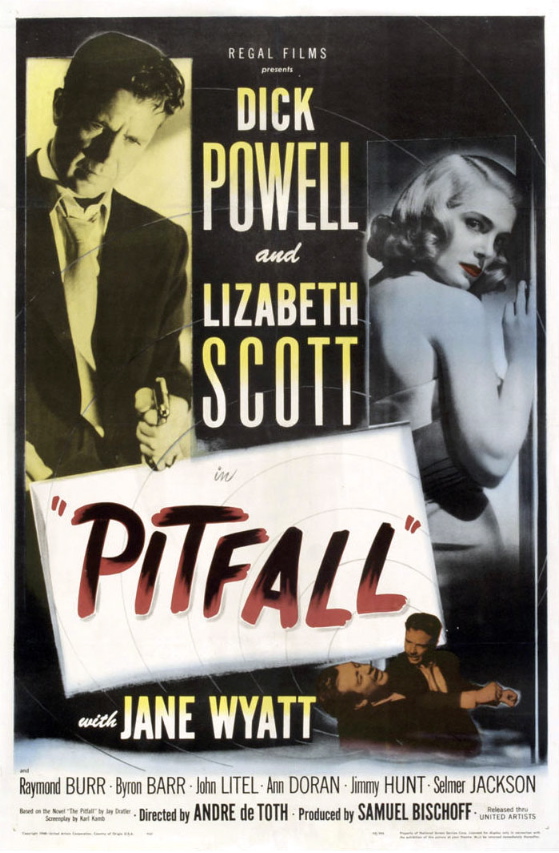

log, I was recently able to view André de Toth's remarkable film Pitfall, from 1948.

Joe thought I might find it an interesting example of domestic noir

— and on many levels that's just what it is . . . a taut, harrowing

thriller about a man whose good marriage is threatened in violent ways

by a moment's indiscretion. The film's tough, snappy, cynical

dialogue bears favorable comparison with the dialogue in Double Indemnity — and the moral confusion of the protagonist, played by Dick Powell, is pure noir. (We also get to see Raymond Burr in one of his earliest noir villain roles.)

But there's something unusual about this film — something that distinguishes it from true noir and from the films I think of as domestic noir. It's the way that the institution of marriage, and the women in the film, are portrayed.

Lisbeth Scott, in what ought to be the femme fatale role, isn't fatale

at all, in the end. She's the victim of male obsession and

mendacity, who's destroyed when she tries to strike back. What's important, though, is that we see

the predicament she's in from her point of view — not from the point

of view of the men who don't understand her or fear her, as we would in

a classic noir.

(The oddness of this is only reinforced by the copy on the lobby card

above, which tries to sell the Scott character as a typical femme fatale — assuming that that's what audiences of the time were looking for.)

More remarkably, Powell's wife in the film, wonderfully played by Jane Wyatt, is a

true partner — neither delivering angel nor destructive goddess, the

two poles of womanhood in the classic noir. Pitfall

offers one of the best and most convincing portraits of a good marriage

in all of cinema — which takes it far from the rancid view of married

life found in almost all domestic noirs.

This film, in fact, presents marriage as a viable refuge from the moral

maze, the existential dread, of post-war American life — and it does

so without a trace of piety or sentiment. Like young Charley in Shadow Of A Doubt, Powell's character in Pitfall

feels trapped by family life at the beginning of the film — only to

discover in the end that it's the only thing in his life that makes any

sense at all. It's a way out that's almost always denied to the protagonist of a classic noir, lost in the labyrinth of noir's dark city — and a view of marriage that's unknown in the moral chaos of a classic domestic noir.

I guess this film belongs in a category all its own — anti-noir.

[In honor of Pitfall I've added a new category to my Film Noir Master List — Sui Generis, for noirish films that aren't like any other films noirs. So far it has two entrants, the anti-noir Pitfall and the schizo-noir Trapped.]

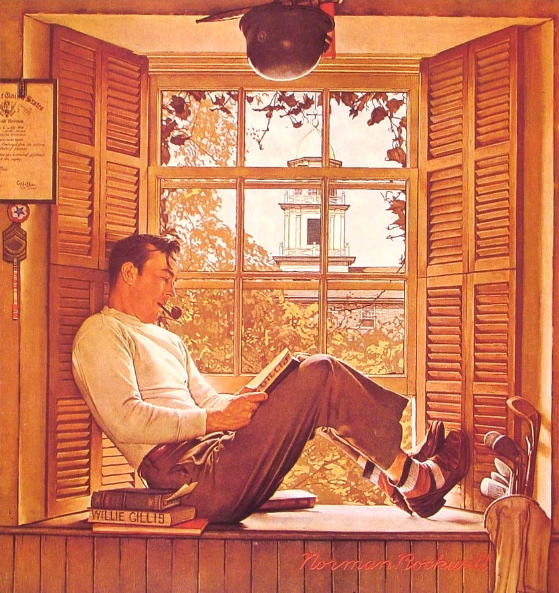

During the WWII years Norman Rockwell created a character named Willie

Gillis — an ordinary guy from a small town who joined the army.

Rockwell chronicled his experiences in the war in a series of Saturday Evening Post

covers. After the war, he showed us Gillis returned to civilian

life — above you see him in college, on the G. I. Bill, having

survived and put on a little weight.

It's a poignant image, for all it doesn't say. Gillis is

preparing himself for a “normal” life in post-war America, with his

pipe and his golf clubs — but the war souvenirs hanging over his head

suggest that he will always be haunted by memories out of place in a

“normal” world.

One of the virtues of Ken Burns' newest documentary The War

is that it addresses the sort of post-traumatic stress disorder that

returning vets, and the whole civilized world on some level, suffered

in the wake of WWII. For the vets it was peculiarly disorienting,

with feelings of triumph, guilt and shame all mixed up together.

It was

not something that could be talked about in the world Willie Gillis was

trying to become a part of.

All of this I think reinforces my notion that it was in art, in film noir

particularly, that such disorientation could be engaged in a safe way,

a socially acceptable way. You can read more thoughts on

the subject here.

The subject matter of The Big Combo, a terrific B-picture from 1955, might have easily been treated within the confines of a late-era crime melodrama or a police procedural —

instead it lurches instantly into the territory of the classic film noir and never leaves it, at least not for long. It’s something you might expect from its director Joseph H. Lewis, who also directed Gun Crazy, one of the darkest and bleakest of all noirs.

The Big Combo is about a policeman’s attempt to bring down a modern crime lord, Mr. Brown — a man so rich and powerful that he never has to soil his own hands with

the dirty work. The police don’t have the financial resources to investigate his multifarious organization, the big combo of the film’s title, and Brown has enough friends in high places to put pressure on any cop who does try to go after him.

Cornell Wilde plays the one cop who won’t give up, won’t buckle under the pressure, and his boss thinks he’s lost his mind. Fighting Brown is fighting the corruption of the whole world — a fool’s errand. It’s Wilde’s essential loneliness that makes him a classic noir protagonist. He doesn’t represent the decent forces in society opposed to “respectable” thugs like Brown — those forces simply don’t exist. This is what distinguishes The Big Combo from a traditional crime melodrama or police procedural.

At the same time, Wilde’s detective is hardly pure himself. It’s suggested that he secretly admires Brown, is secretly in love with Brown’s moll — that his crusade is motivated more by jealousy and resentment than by morality or a love of justice. This is what distinguishes the protagonist of this film from the traditional “tarnished knight” hero of traditional hardboiled detective fiction. The code of honor of the Wilde character is suspect.

At one point the moll, explaining why she can’t leave Brown, says, “I

live in a maze . . . a strange, blind and backward maze, and all the

little twisting paths lead back to Mr. Brown.” That’s the

predicament of Wilde’s character as well. By the end of the film,

the view of the world we’ve been given makes it quite irrelevant

whether or not Brown is ever brought to justice. There’s no sense

that the world will be a better place if he is, because it will still

operate by the same rules — Brown’s rules.

The Wilde character’s fight to extricate himself from the maze is

heroic. He will save a few lives and avenge a few others along

the way, but his existential dilemma will never be resolved, because

the big combo is the world and it won’t change. It will stay noir.

The ending of The Big Combo echoes the ending of Casablanca visually. But what different moral universes the two films inhabit. In 1942, Casablanca could make idealistic sacrifice look glamorous and sexy. By 1955, ten years after the end of WWII, the cost of such sacrifice had been measured. We had defeated the Axis evil, but to do so we had had to summon up reserves of evil within ourselves, and the ghost of it hovered, in the shape of a mushroom cloud, over everything.

The Big Combo has been added to my film noir canon. Sadly, there isn’t a satisfactory DVD edition of the film, although the Geneon release is watchable and cheap. The Big Combo deserves better, if only for the wonderfully inventive cinematography of the

great noir master John Alton.