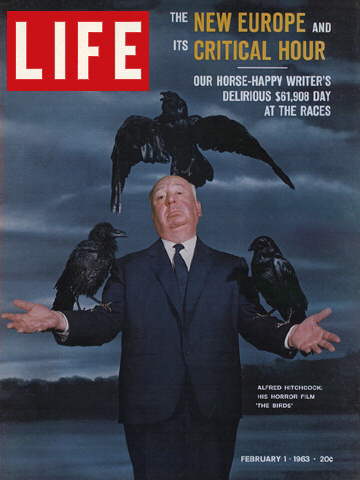

Dr. Drew Casper is the Alfred and Alma Hitchcock Professor Of American Film at the University of Southern California. He is a published author on film. I assume that the “Dr.” in front of his name means that he has a PhD. Casper shows up often delivering “expert commentary” on DVDs. I assume that he speaks English as a first language but somehow in his journey through academia he has not managed to master the rudiments of his native tongue.

His style of speaking involves a lot of rephrasing, designed, I suppose, to suggest the addition of nuance to the points he's making but adding up only to redundancy. In his commentary on the recent DVD release of Notorious, for example, he says that Alicia “is out of control — she has lost control.” These two phrases mean exactly the same thing — one or the other would have served perfectly well. He refers to the famous key in the film as “a prop — an object, if you want.” Yes, I will accept that a prop is an object, since a prop is always an object. It's sort of like saying, “a person — a human being, if you want.” This is a form of pretentious bloviation.

Casper misspeaks constantly in his commentary. He says that Alex's mother “yields a lot of power” in Alex's home, when he means that she wields a lot of power. Of a traveling shot close on Alicia and Devlin, Casper says it suggests that they are “floating on air, existing gravity.” I'm not even sure what he actually meant to say there — “resisting gravity”? Who knows?

Casper introduces the subject of Russian Constructivism and then goes on to refer to it more than once as Roman Contructivism, whatever that might be. Casper also misuses language freely. He says that German filmmakers “triumphed” the use of lighting as an expressive tool. He doesn't seem to know or care that “triumph” is an intransitive and never a transitive verb.

The professor is promiscuously careless about details as well. He refers to the German director “D. W. Pabst”. He says at one point that Alex is taller than Alicia, when he's just been talking about the significance of him being shorter. He says that in Hitchcock's films special effects are always in the service of technique, when he means always in the service of story or character.

Is there no editor or director present when Casper records his commentaries? Doesn't Casper, or someone, listen to them after they're recorded to catch mistakes and suggest retakes? Or is it the case that any old nonsense from the mouth of a man with a PhD is assumed to be authoritative?

Casper is not an idiot — he has many interesting things to say about the themes and strategies of Notorious — but he seems to feel no obligation whatsoever to present his analysis with even a modicum of intellectual rigor or discipline. If Hitchcock had had the same attitude about filmmaking that Casper has about film criticism, we wouldn't be watching Hitchcock's films today. Bloviating about them in such a scatter-brained way is a kind of insult to Hitchcock's professionalism.

Casper's poor language skills offer a terrifying insight into the modern academy, and modern academic standards in the area of film studies. Presumably Casper doesn't fear that his students will note, much less correct, his mangling of English, though some of them would undoubtedly be capable of doing so. They want good grades from him, after all. Presumably, as the occupant of an endowed chair at his university, probably a tenured position, he doesn't fear the criticism of his fellow professors or supervisors, who would have a very hard time removing him from his job. Perhaps they feel that since film is a visual medium, there's no need to speak about it in precise and correct language.

It's all very depressing. When a professor at a major American university can get away with such shoddy speech, it's no wonder that American institutions of higher learning are turning out graduates who are semi-literate, who not only speak but think sloppily about film, among other things.