[With plot spoilers — don't read what follows unless you've seen the film . . .]

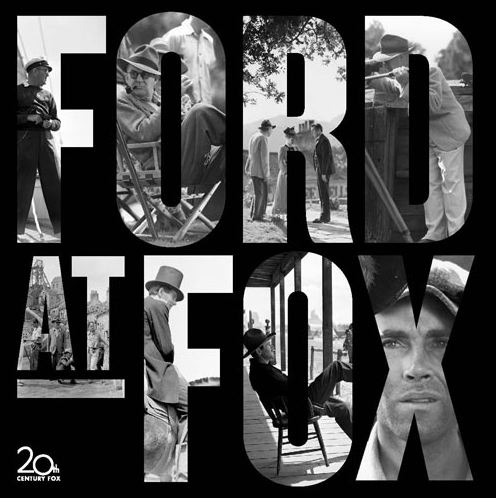

Pilgrimage,

a John Ford film from 1933, is unapologetic melodrama — it makes a

shameless appeal to the emotions. A modern sensibility, schooled

in a cynical age, tends to resist this sort of appeal and I did, too,

the first two times I saw the film, and it worked — up to a point. Beyond that point I found myself crying

like a baby. I'm still not entirely sure how Ford got around my

defenses (twice!) but I'm

forced to admit that he deployed the complex and mysterious resources

of melodrama with devastating effectiveness.

One of the key resources of melodrama, especially cinematic melodrama,

is indirection — while the conscious mind is busy resisting the

obvious assault on the heartstrings, the filmmaker finds an unexpected

avenue around the conscious mind, and the emotion catches you unawares

by some other route than the one you were defending.

Pilgrimage tells the story of

a possessive mother who ships her son off to WWI rather than lose him

to the young woman he plans to marry — and the kid dies “over

there”. The fiancée is pregnant with the boy's child, whom the

grandmother refuses to recognize. Something has to give — but

where, and how?

The first radical shift in the tone of the film is visual rather than

(explicitly) emotional. The embittered old woman is offered a

trip to France to visit her son's grave and is shamed by her neighbors

into going. We cut to the station where she's boarding her

train, and the cut is a shock — because the station is an exterior

location, shot in sunlight . . . the first such shot in the film.

Everything else, even the rural exteriors, has been shot on a sound

stage, with moody, often expressionistic lighting. (There is a

single shot prior to this, of a moving train at night, which couldn't

have been shot on a sound stage but might as well have been — all we

see is the train surrounded by darkness.)

From this point on in the film, Ford shoots on real exterior locations or sets built out-of-doors

as often as he can. Real sunlight becomes a player in the

tale. You don't need to notice this consciously for it to have

its effect. It's disarming. It prepares us for deeper

changes. At the station, the mother of her son's child asks the

old woman to take a bouquet of flowers to the grave for her. She

raises it up to the window of the train compartment where the old woman

is sitting, unseen by us. Slowly the old woman's hand reaches out

and takes the bouquet, draws it in to the train.

We never see the old woman's face in this exchange — and we really

want to. We want to know if she takes the flowers angrily or

tenderly, if she's softening or still hard as stone. Ford

won't tell us. The next time we see her, we look at her a bit

more closely — suspicious that Ford might be keeping something else

from us. We might think we don't care about this old woman and

her damned intransigence — but the damned director better not try to

hold out on us like that again. It's a master melodramatic stroke.

As we watch what happens to the old woman in France, surrounded by

other mothers who lost sons in the war, things develop in a conflicted

and complicated way. The old woman finds a kind of companionship

she's never known in her life — and we suddenly realize the depth of

the loneliness that made her want to hang on to her son. We'd

been looking at the pathology of it before, at its horrifying effects

on other people's lives — now we're blindsided by an awareness of the

unutterable isolation and sadness at the core of her being. She

doesn't seem so much delighted as bewildered by her ability to get on

with others — and that's what breaks our hearts

But as the old woman comes alive among her peers, she also grows more

distant from them, dealing with the fact that they mourn loving relationships

with loving sons while she wrecked her son's life, and sent him off to

die. She faces up to her guilt with courage but it estranges her

from these woman in whose company she has blossomed as a human being

for perhaps the first time.

In Ford films, of course, with their strong Christian, Catholic

underpinnings, facing up to one's sins leads to redemption — often by

miraculous means. In this case it's a young suicidal man the old

woman meets on the street and saves from himself — a surrogate son,

who gives her a second chance to be a good mother. This doesn't

remove her burden, but it gives her the final measure of courage she

needs to visit her son's grave.

That visit is shot on an exterior set built inside a sound stage, lit

moodily,

with a long tracking shot through the crosses in the graveyard.

Stylistically, we're back where we started in the film — we have made

a kind of circle through the sunlight and come back to the shadows

again. The old woman places the withered bouquet given to her by

her son's fiancée on the grave — then falls into the dirt and asks her

son's forgiveness. She's saved — and somehow Ford has badgered,

enchanted and tricked us into following the mechanics of her salvation,

believing in them because we have felt them, in spite of

ourselves. The Christian dynamic of confession, repentance and

redemption is rendered in convincing psychological terms.

In one sense, it's all done with mirrors, with clever deviations and

circumnavigations around the story's deep undertow — but the tears it

draws out of us, the tears it allows us, finally, to release, are quite real . . . and precious.